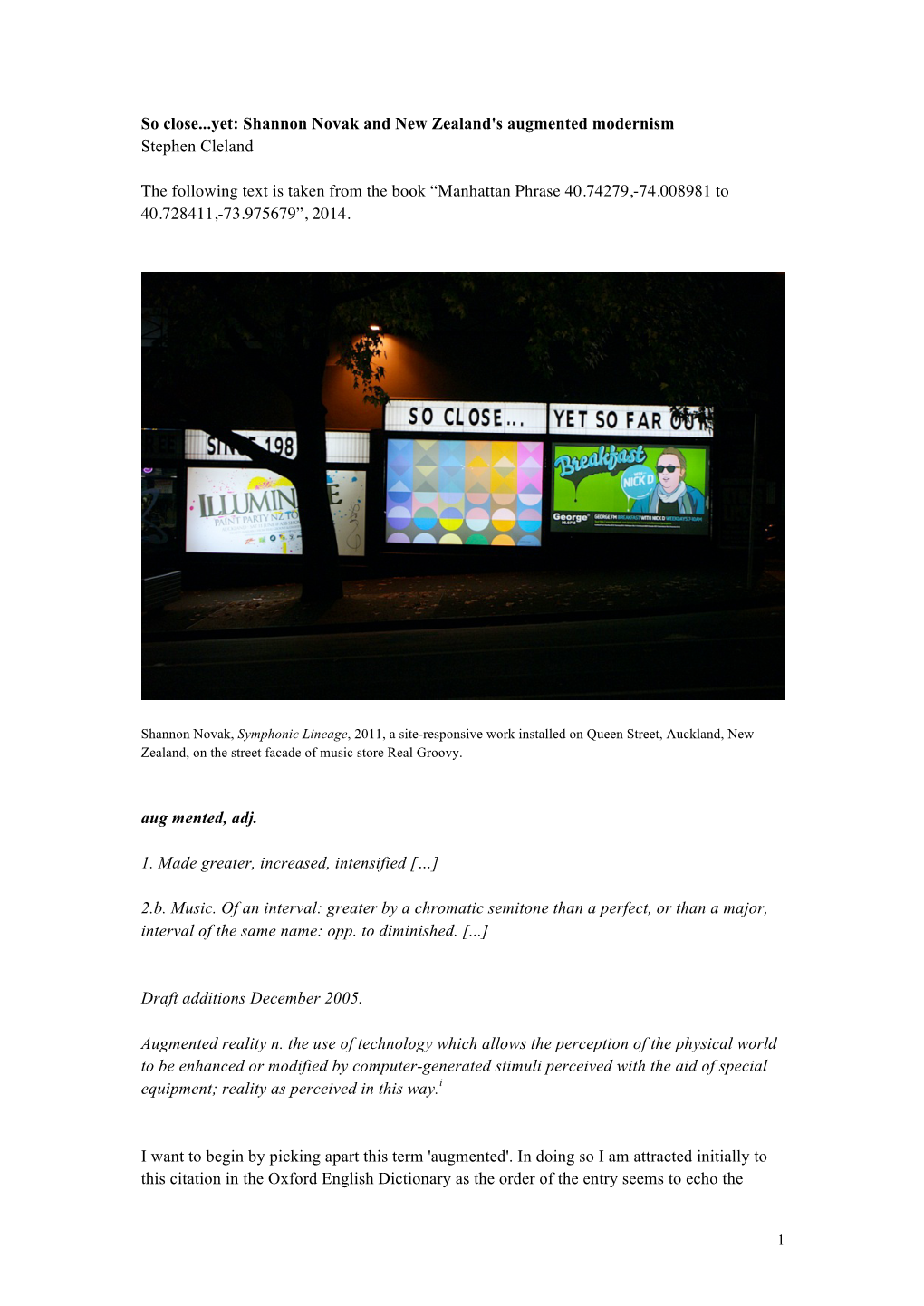

Essay by Stephen Cleland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ascent03opt.Pdf

1.1.. :1... l...\0..!ll1¢. TJJILI. VOL 1 NO 3 THE CAXTON PRESS APRIL 1909 ONE DOLLAR FIFTY CENTS Ascent A JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND The Caxton Press CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND EDITED BY LEO BENSEM.AN.N AND BARBARA BROOKE 3 w-r‘ 1 Published and printed by the Caxton Press 113 Victoria Street Christchurch New Zealand : April 1969 Ascent. G O N T E N TS PAUL BEADLE: SCULPTOR Gil Docking LOVE PLUS ZEROINO LIMIT Mark Young 15 AFTER THE GALLERY Mark Young 21- THE GROUP SHOW, 1968 THE PERFORMING ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EXPLOSIVE KIND OF FASHION Mervyn Cull GOVERNMENT AND THE ARTS: THE NEXT TEN YEARS AND BEYOND Fred Turnovsky 34 MUSIC AND THE FUTURE P. Plat: 42 OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 47 JOHN PANTING 56 MULTIPLE PRINTS RITA ANGUS 61 REVIEWS THE AUCKLAND SCENE Gordon H. Brown THE WELLINGTON SCENE Robyn Ormerod THE CHRISTCHURCH SCENE Peter Young G. T. Mofi'itt THE DUNEDIN SCENE M. G. Hire-hinge NEW ZEALAND ART Charles Breech AUGUSTUS EARLE IN NEW ZEALAND Don and Judith Binney REESE-“£32 REPRODUCTIONS Paul Beadle, 5-14: Ralph Hotere, 15-21: Ian Hutson, 22, 29: W. A. Sutton, 23: G. T. Mofiifi. 23, 29: John Coley, 24: Patrick Hanly, 25, 60: R. Gopas, 26: Richard Killeen, 26: Tom Taylor, 27: Ria Bancroft, 27: Quentin MacFarlane, 28: Olivia Spencer Bower, 29, 46-55: John Panting, 56: Robert Ellis, 57: Don Binney, 58: Gordon Walters, 59: Rita Angus, 61-63: Leo Narby, 65: Graham Brett, 66: John Ritchie, 68: David Armitage. 69: Michael Smither, 70: Robert Ellis, 71: Colin MoCahon, 72: Bronwyn Taylor, 77.: Derek Mitchell, 78: Rodney Newton-Broad, ‘78: Colin Loose, ‘79: Juliet Peter, 81: Ann Verdoourt, 81: James Greig, 82: Martin Beck, 82. -

Vladamir Cacala and the Gelb House (1955) G. Elliot Reid

Vladamir Cacala and the Gelb House (1955) G. Elliot Reid Eisenman writes of a "modernism of alienation"1 which arises in the anxiety of dislocation, an architecture of "an alienated culture with no roots." "Architecture has repressed the individual consciousness in the physical envi ronment that is supposed to be the happy home. I think it is exactly in the home where the unhomely is, where the terror is alive-in the repression of the unconscious. What I am trying to suggest is that the alienated house makes us realise that we cannot only be conscious of the physical world, but rather also of our own consciousness. "2 I feel that a rootless alienated repression can be a central fact of life in New Zealand, par ticularly for the exiled immigrant, to which architecture on the whole usually chooses to 'turn a blind eye,' that architecture refuses to engage with a social disintegration and a repression, preferring instead to fragment itself, submerge itself uncritically into its own condition. 75 The Gelb House I refer to a work by such an exile, Vladimir Cacala, the Gelb House, Mount Albert (1955). Cacala's work on the whole remained committed to a small circle of influences, choosing to explore a reduced vocabulary of architectural forms. (This alien ground holds no memory, no associative value for Cacala.) The typical Cacala house comprises two enveloping walls with large expanses of glass to the north; planes pushed forward at floor and roof level in the manner of Richard Neutra (for example the Kun house, 1936, or the Davis house, 1937). -

Webb's Suite of Winter Sales

The Aucklander 16 July 2009 15 SPORT Turbo-charged andreadyto go This Kumeu sportswoman is fired up over anew sport that’s about to take the city by storm. She tells Andrea Warmington why it’s so much fun ewa Ross is kicking off asporting use the whole court, rather than the line forma- revolution. tion of traditional touch. Well, perhapsnot kicking off. In contrast to the outdoor version, in which R The Kumeu sportswoman is one of the only the fastest players usually score tries, any- first to sign up for turbo touch —anew one can reach turbo’s end-zone. sport that combines rugby, netball and basket- Netball, rugby, American football and Aussie ball. Rules-style passing helps get anyone over the It begins, officially, in Auckland on July 17. line for atouchdown. ‘‘I had to have ago,’’ she says, ‘‘and once I’d Like touch —played by 317,000 New Zea- had ago, Ihad to have anothergo.’’ landers —turbo touch is fast-paced and all over Touch New Zealand is promoting turbo in just 40 minutes. touch as awinter, indoor version of its outdoor ‘‘My husband doesn’t like netball, but he game and has held trial nights around the likes touch. He came along and really enjoyed region. it,’’ says Mrs Ross. Played on abasketball court rather than on a The first Auckland turbo touch tournament rugby field, turbo touch allows players to pass will be played at the Trusts Stadium Arena on the oval ball sideways, backwards and forwards. July 17. ‘‘It’s all about positioning, teamwork and On July 24, turbo touch will hold another TURBO TOUCH FAN REWA ROSS strategy,’’ says Mrs Ross. -

Glenn Schaeffer Collection

THE GLENN SCHAEFFER COLLECTION SCHAEFFER GLENN THE THE ART + OBJECT GLENN SCHAEFFER COLLECTION ART + OBJECT 31 October 2017 121 AO1183FA Schaeffer covers.indd 1 11/10/17 4:31 PM ART + OBJECT 31 October 2017 AO1183FA Schaeffer covers.indd 1 11/10/17 4:31 PM THE GLENN SCHAEFFER COLLECTION ART+OBJECT When Glenn Schaeffer speaks one is inclined to listen. This is not say he is loud, brash or that he has a great deal to say, or any other American stereotype one might associate. Rather, it is quite the opposite. It may well be because he possesses a Master of Arts in Literature, a Master of Fine Arts in Fiction and a Litt D. (Hons) from our own Victoria University in Wellington. It could also be because, as The Listener magazine wrote, he is arguably the single biggest influence on New Zealand literature in this country and an exceedingly generous philanthropist. Schaeffer first visited New Zealand in 1994 and since then has immersed himself wholeheartedly in the literary and visual arts scene in this country. His commitment to the arts goes well beyond his propensity for collecting major New Zealand, Australian and American artworks to being the founding patron and benefactor of Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters which awards the biannual Prize in Modern Letters to major new writers. He is also a benefactor of Nelson’s Suter Gallery. Schaeffer is also, of course, a very successful businessman. He was formerly President and Chief Financial Officer of Las Vegas-based Mandalay Resort Group for twenty years, one of America’s top hospitality and entertainment companies. -

The Romance of the Fresh Page

Fortnightly newsletter for University staff | Volume 39 | Issue 7 | 1 May 2009 The romance of the fresh page Key events Research excellence Invited staff will gather in the marquee on the lawn of Old Government House on 5 May at 5pm to celebrate the University’s continued excellence in research, the success of those who have been granted research awards and contracts, and the launch of research-related initiatives including many commercial outcomes. Hosting the evening will be the Vice- Chancellor Professor Stuart McCutcheon, the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research) Professor Jane Harding, and CEO of UniServices Dr Peter Lee. Perhaps love The Confucius Institute is running free movie nights, featuring exciting productions from Elizabeth Caffin receives her honorary doctorate. China. On 7 May is Perhaps Love, a lavish award-winning 2005 musical – the first to be An honorary doctorate has been bestowed on numerous capacities. “She is also a respected made in China in 40 years. Directed by Elizabeth Caffin who earned Auckland University writer and reviewer.” acclaimed filmmaker Peter Chan, it tells of the Press growing renown during her two decades at In her eulogy the Public Orator, Professor Vivienne love triangle between a handsome actor, his the helm. Gray, noted that university presses “have a special beautiful co-star, and a talented film director. She received an honorary Doctor of Literature commitment to scholarship and to language and to Lin (Takeshi Kaneshiro) and his ex-lover Sun degree at the Maidment Theatre on 7 April in front writing skill, which reaches a peak in poetry. (Zhou Xun) are shooting a movie for director of family, friends, authors and colleagues. -

Download PDF Catalogue

THE 21st CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE A+O 7 A+O THE 21st CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE 3 Abbey Street, Newton PO Box 68 345, Newton Auckland 1145, New Zealand Phone +64 9 354 4646 Freephone 0800 80 60 01 Facsimile +64 9 354 4645 [email protected] www.artandobject.co.nz Auction from 1pm Saturday 15 September 3 Abbey Street, Newton, Auckland. Note: Intending bidders are asked to turn to page 14 for viewing times and auction timing. Cover: lot 256, Dennis Knight Turner, Exhibition Thoughts on the Bev & Murray Gow Collection from John Gow and Ben Plumbly I remember vividly when I was twelve years old, hopping in the car with Dad, heading down the dusty rural Te Miro Road to Cambridge to meet the train from Auckland. There was a special package on this train, a painting that my parents had bought and I recall the ceremony of unwrapping and Mum and Dad’s obvious delight, but being completely perplexed by this ‘artwork’. Now I look at the Woollaston watercolour and think how farsighted they were. Dad’s love of art was fostered at Auckland University through meeting Diane McKegg (nee Henderson), the daughter of Louise Henderson. As a student he subsequently bought his first painting from Louise, an oil on paper, Rooftops Newmarket. After marrying Beverley South, their mutual interest in the arts ensured the collection’s growth. They visited exhibitions in the Waikato and Auckland and because Mother was a soprano soloist, and a member of the Hamilton Civic Bev and Murray Gow Choir, concert trips to Auckland, Tauranga, New Plymouth, Gisborne and other centres were in their Orakei home involved. -

From the Adriatic Sea to the Pacific Ocean the Croats in New Zealand

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 18, 2009, 2, 232-264 FROM THE ADRIATIC SEA TO THE PACIFIC OCEAN THE CROATS IN NEW ZEALAND Hans-Peter STOFFEL School of European Languages and Literatures, University of Auckland, 14a Symonds St, New Zealand [email protected] The Croatian Community in New Zealand has a unique history. It is about 150 years old, its earliest arrivals were mainly young men from the Dalmatian coast of whom almost all worked as kauri gumdiggers before moving into farming, and then into viticulture, fisheries and orchard business. Before large-scale urbanisation in the 1930s they lived in the north of New Zealand where there was also considerable contact with the local Maori population. The arrival of ever more women from Dalmatia, urbanisation and with it the establishment of voluntary associations, an improved knowledge of English, the language of the host society and, above all, economic betterment led to ever greater integration. After World War II migrants from areas of former Yugoslavia other than Croatia started to arrive in bigger numbers. Nowadays Croat people can be found in all spheres of New Zealand society and life, including in the arts, literature and sports. But the history of the Croats in New Zealand is also characterised by its links with the 'Old Country' whose political and social events, the latest in the 1990s, have always had a profound influence on the New Zealand Croatian community. Key words: Croatian chain migration to and from New Zealand, Croatia(n), Dalmatia(n), Yugoslavia, Austria-Hungary, kauri gumdigging, economic advancement, integration into Maori and Pakeha (white) host societies, women, urbanisation, voluntary associations, New Zealand Croatian culture, New Zealand Croatian dialects On 22 November 2008 the Croatian community in New Zealand celebrated the 150th anniversary of the arrival of Paval Lupis from Dalmatia in New Zealand in 1858. -

Redressing Theo Schoon's Absence from New Zealand Art History

DOUBLE VISION: REDRESSING THEO SCHOON'S ABSENCE FROM NEW ZEALAND ART HISTORY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History in the University of Canterbury by ANDREW PAUL WOOD University of Canterbury 2003 CONTENTS Abstract .......................................... ii Acknowledgments ................................. iii Chapter 1: The Enigma of Theo Schoon .......................... 1 Chapter2: Schoon's Early Life in South-East Asia 1915-1927 ....... .17 Chapter 3: Schoon in Europe 1927-1935 ......................... 25 Chapter4: Return to the Dutch East-Indies: The Bandung Period 1936-1939 ...................... .46 Chapter 5: The First Decade in New Zealand 1939-1949 ............ 63 Chapter 6: The 1950s-1960s and the Legacy ......................91 Chapter 7: Conclusion ...................................... 111 List of Illustrations ................................ 116 Appendix 1 Selective List of Articles Published on Maori Rock Art 1947- 1949 ...................................... 141 Appendix 2 The Life of Theo Schoon: A Chronology ................................... .142 Bibliography ..................................... 146 ABSTRACT The thesis will examine the apparent absence of the artist Theo Schoon (Java 1915- Sydney 1985) from the accepted canon ofNew Zealand art history, despite his relationship with some of its most notable artists, including Colin McCahon, Rita Angus and Gordon Walters. The thesis will also readdress Schoon's importance to the development of modernist art in New Zealand and Australia, through a detailed examination of his life, his development as an artist (with particular attention to his life in the Dutch East-Indies, and his training in Rotterdam, Netherlands), and his influence over New Zealand's artistic community. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgment and thanks are due the following: My thesis supervisor Jonathan Mane-Wheoke, without whose breadth of knowledge and practical wisdom, this thesis would not have been possible. -

Auckland Art Gallery Toi O Tāmaki Exhibition History

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki Exhibition History To search Press Ctrl F to do a keyword search Index Browse by clicking on a year (click on top to return here) 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1933 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 1927 top 23 Jun 27 – 16 Jul 27 A Collection of Old and Modern Etchings on Loan from Auckland Collectors Catalogue 25 Oct 27 – 30 Nov 27 Loan Collection of Japanese Colour Prints from Mr H.S. Dadley and Capt. G. Humphreys-Davies Catalogue 1928 top Australian Etchings 1929 top 1 Aug 29 – 24 Aug 29 Loan Collection of Prints Illustrating the Graphic Arts Catalogue 1930 top 7 Apr 30 – 26 Apr 30 Loan Collection of Bookplates Catalogue 6 Aug 30 – 30 Aug 30 Loan Collection of Prints: Representative of Graphic Art in New Zealand Catalogue 23 Sep 30 – 14 Oct 30 Loan Collection of Photographs by Members of the Camera Club of New York and Dr Emil Mayer Catalogue 22 Oct 30 – 12 Nov 30 Medici Prints: Dutch, Flemish and German 17 Nov 30 – 2 Dec 30 Medici Prints: English 5 Dec 30 – Dec 30 Medici Prints: Italian and French 1931 top 24 Nov 31 – Jan 32 Prints from the Collection Illustrating Various Methods 1932 top 28 Jan 32 – 1 Jun 32 Medici -

From the Collection There Is Still Time PEN Winner

From the collection Art art and would later introduce him to Mäori rock arrangement on canvas. This repetition of forms art in South Canterbury. Walters was particularly using a reduced colour palette anticipates the attracted to the European surrealists, including formal relationships of his later work, but in this Paul Klee and Joan Mirò, and their inspiration in case is more intuitively placed. Lastly, the the subconscious and “primitive” forms. wandering line is established by dropping a string Walters made several trips to Australia before on the canvas, a technique used in several works, he left New Zealand in 1950 for London, also which recalls the chance experiments of the visiting Paris and Amsterdam, and encountering surrealists, as well as their interest in the psyche. first-hand the abstract works of Piet Mondrian, Schoon also seeded Walters’ interest in Mäori Jackson Pollock and Victor Vasarely, the latter a moko and kowhaiwhai designs, leading to particular influence on his early non-figurative Walters’ first kowhaiwhai patterns in 1957, works, executed once back in Melbourne in 1952. followed by his first experiments with his In 1953 he found himself in Auckland for a trademark koru design in 1958, largely working Gordon Walters (1919-1995), Untitled, 1955, oil on period before returning to Wellington to work for on paper with pencil, gouache and brush. Since he canvas, 510 x 606mm. The University of Auckland Art the Government Printing Office. While working, was nervous about their reception in conservative Collection. through the mid-1950s, Walters would produce New Zealand, it wasn’t until 1966 that Walters hundreds of small works on paper, not having any publicly exhibited his now-famous koru works, The emergence in the 1950s of Gordon Walters audience to develop larger pieces for. -

A.R.D. Fairburn Juliet Peter Robert Ellis Roy Eeks Don Driver Roy Cowan

JOSE BRIBIESCA DON RAMAGE A.R.D. FAIRBURN JULIET PETER ROBERT ELLIS ROY GOOD EILEEN MAYO JOHN WEEKS DON DRIVER ROY COWAN GARTH CHESTER BOB ROUKEMA JOHN CRICHTON LEN CASTLE MODERNISM IN RUSSELL CLARK MERVYN WILLIAMS COLIN McCAHON TED DUTCH NEW ZEALAND ANDRE BROOKE FRANK HOFMANN FREDA SIMMONDS GREER TWISS THEO SCHOON ROSS RITCHIE GEOFFREY FAIRBURN FRANK CARPAY RUTH CASTLE JOVA RANCICH JOHN MID- DLEDITCH ELIZABETH MATHESON MIREK SMISEK RICHARD PARKER JEFF SCHOLES ANNEKE BORREN ROBYN STEWART PETER STICHBURY MILAN MRKUSICH BARRY BRICKELL JEAN NGAN VIVIENNE MOUNTFORT GEORGIA SUITER THEO JANSEN DA- VID TRUBRIDGE CES RENWICK EDGAR MANSFIELD PETER SAUERBIER STEVE RUM- SEY DOROTHY THORPE LEVI BORGSTROM SIMON ENGELHARD TONY FOMISON PAUL MASEYK RICK RUDD DOREEN BLUMHARDT A RT+O BJ EC T LEO KING PATRI- CIA PERRIN DAVID BROKENSHIRE MANOS NATHAN 21 MAY 2014 WI TAEPA MURIEL MOODY WARREN TIPPETT ELIZABETH LISSAMAN BUCK NIN E.MERVYN TAYLOR AO722FA Cat78 cover.indd 1 5/05/14 1:34 PM AO722FA Cat78 cover.indd 2 5/05/14 1:34 PM Modernism in New Zealand Wednesday, 21 May 2014 6.30pm AO722FA Cat78 text p-1-24.indd 1 6/05/14 1:02 PM Inside front cover: Inside back cover: Frank Hofmann, A.R.D. Fairburn, Composition with Study of Maori Rock Cactus, 1952 (detail), Drawings (detail), Be uick. vintage gelatin silver vintage screenprinted print. Lot 274. fabric mounted to “Strictly speaking New Zealand doesn’t board. Lot 251. Looking for a Q? At these extraordinary prices you’ll have to hurry. exist yet, though some possible New Zealands glimmer in some poems and in some canvases. -

AUSTRALIA 6 NEW ZEALAND: on the Road with Jah

VOLUME 5, NUMBER 4 SEPf EMBER 1982 AUSTRALIA 6 NEW ZEALAND: on the road with jah Editor's Note: This is the second article in a series on my recent visit to Australia and New Zealand, sponsored by Art Network and funded by the Australian Council and the Queen Elizabeth XI Arts Council of New Zealand. This article focuses in on New Zealand and my two weeks there. part I1 What do you say when the first stop in a new country is on the lip of a volcanic crater, called Mt. Eden? This was my in- troduction to New Zealand, home of the Maoris, alps and Rotorua, where tranquillity is translated into life, where soci- ety is at home with nature, and where "Noise Annoys" appears on cancelled envelopes in the mail. Looking down on Auckland with Valerie Richards, librarian at the Fine Arts Library at the University of Auckland and the arranger of my tour in her country, I thought I saw a miniature Los Angeles glistening at night, but in fact it was a city called Auckland with 800,000 inhabitants stretched around for 30 miles. Sunday brunch produced myriads of women artists, as well as Wystan Curnow, famed art and literary critic and poet from the University of Auckland, Phil Dadson, new music performance artist, and much more. Auckland is a verv beautiful citv, surrounded bv water, but all of New Zealand seems surrounded by water, for it is a narrow island At lunch, I met such a fine printer, Nigel Thorp, who has and water does predominate as does sky-skies which you over 100 fonts of wooden type and ornaments, and loves to must experience to believe.