Benjamin Banneker: Surveyor, Astronomer, Publisher, Patriot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iowner of Property

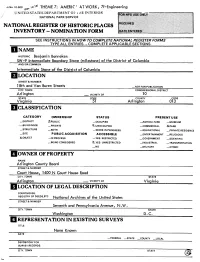

A.NO. 10-300 ^.-vo-'" THEME 7: AMERIC' AT WORK, 7f-Engineering UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT Or ( HE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS _____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Benjamin Banneker: SW-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone (milestone) of the District of Columbia______ AND/OR COMMON Intermediate Stone of the District of Columbia LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 18th and Van Buren Streets _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Arlington VICINITY OF 10 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Virginia 51 Arlington 013 UCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT .X.PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^_ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL 2LPARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS X-OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Arlington County Board_______ STREET & NUMBER Court House, 1400 N Court House Road CITY. TOWN STATE Arlington VICINITY OF Virginia LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. NaHonal Archives of the United States STREET & NUMBER Seventh and Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None Known DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE _GOOD —RUINS X.ALTERED —MOVED DATE- X.FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The SW-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone of the District of Columbia falls on land owned by Arlington County Board in the suburbs known as Falls Church Park at 18th Street and Van Buren Drive, Arlington, Virginia. -

HO-313 George Anderson Shop

HO-313 George Anderson Shop Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 02-07-2013 HO-313 Day-O'Neal-French House 3723 Old Columbia Pike Private Description: The Day-O'Neal-French House is a three-story, three-bay by two-bay brick structure that appears to have running bond on the northwest elevation and what appears to be four-to-one common bond on the other elevations. It has a rubble stone foundation and a gable roof with asphalt shingles and a northeast-southwest ridge. The house has an interior brick chimney on both gable ends. On the southeast elevation is a three-bay by one-bay, two-story, shed-roofed brick addition with a long, shed-roofed frame dormer on it. -

Fox, ELLICOTT, and EVANS

BIOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF THE Fox, ELLICOTT, AND EVANS FAMILIES, AND THE DIFFERENT FAMILIES CONNECTED WITH THEM. COLLECTED AND COMPILED BY CHARLES W. EVANS, BUFFALO, N. Y. BUFFALO: PRESS OF BAKER, JONES & CO. 1882. PREFACE. OME fifty years ago, before I was twenty, I began to collect material Sfor this family history, but with no intention of publishing it, until within five years past. Many of those who originally gave me the infor -~iati0u, which I at the time committed to writing, have passed away. I remember them with much pleasure, because I took great interest in their narratives. Among them were my father, mother, grandmother, and aunts, and also more distant relatives, such as l\,f ARTHA ELLICOTT CAREY, and her sister, ELIZABETH ELLICOTT, of Avalon; ELIZABETH ELLICOTT, • wife of GEORGE ELLICOTT, of Ellicott's Mills, Md.; THOMAS ELLICOTT, of Avondale, Pa.; RACHEL T. HEwEs; JOHN ELLICOTT, son of ELIAS; and MARTHA E. TvsoN. I have also had access to several fan1ily records, and to 1nany family letters, particularly those to JOSEPH ELLICOTT, of Batavia, N. Y. Among those now living, to none am I so much indebted as to JOHN H. BLISS, of Erie, Pa. Had it not been for his unwearied patience and perseverance in collecting family statistics, not more than half, and perhaps not more than one-£ ourth, of the names, dates; etc., par ticularly those of the youuger branches, could have been obtained. Com paratively few, scarcely any, of those to whom he wrote, refused to give the information asked of them, for which they deserve much credit. -

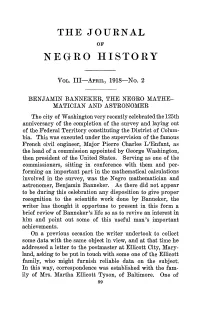

Benjamin Banneker, the Negro Mathematician and Astronomer

THE JOURNAL OF NEGRO HISTORY VOL. III-APRIL, 1918-No. 2 BENJAMIN BANNEKER, THE NEGRO MATHE- MATICIAN AND ASTRONOMER The cityof Washington. very recently celebrated the 125th annivers.aryof the completionof the surveyand layingout of theF'ederal Territory constituting the District of Colum- bia. This was executedunder the supervision of thefamous Frenchcivil engineer,Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant, as thehead of a commissionappointed by GeorgeWashington, thenpresident of theUnited States. Servingas one of the commissioners,sitting in conferencewith themand per- formingan importantpart in themathematical calculations involvedin the survey,was the Negro mathematicianand astronomer,Benjamin Banneker. As theredid not appear to be duringthis celebration any dispositionto give!proper recognitionto the scientificwork done by Banneker,the writerhas thoughtit opportuneto presentin this forma briefreview of Barneker's life so as to revivean interestin him and point out some of this useful man's important achievements. On a previousoccasion the writerundertook to collect somedata withthe same objectin view,and at thattime he addresseda letterto the postmasterat EllicottCity, Mary- land,asking to be put in touchwith some one of theEllicott family,who mightfurnish reliable data on the subject. In thisway, correspondence was establishedwith the fam- ily of Mrs. MarthaEllicott Tyson,of Baltimore. One of 99 100 JOURNALOF NEGRO HISTORY her descendants,Mrs. TysonManly, kindly came over from Baltimore,and, calling on the writerat the United States PatentOffice, presented him with a copyof the life of Ban- neker,published in Philadelphiain 1884,and compiledfrom the papers of MarthaEllicott Tyson, who was the daughter of GeorgeEllicott, a memberof thenoted Maryland family, who establishedthe business that developedthe town of Ellicott City. -

Part One 3/20/00 1:48 PM Page 3

Part One 3/20/00 1:48 PM Page 3 P ART O NE ✦ THE EARLY YEARS Part One 3/20/00 1:48 PM Page 4 Part One 3/20/00 1:48 PM Page 5 B ENJAMIN BANNEKER (1731–1806) ✦ In the decades before the Revolutionary War, which resulted in the founding of the United States, it was widely believed that black people were incapable of intellectual achievement. Slavery and racial discrimination were justified by the argument that black people were no more capable of learning than were animals such as horses and cows. Then along came a man who challenged these assumptions “with the fire of his intellect,” one nineteenth-century historian declared, forcing Thomas Jefferson and others to question their belief in black inferiority.1 The man’s name was Benjamin Banneker, and there is probably no better example of the desire to learn and to teach others than that shown by him throughout his life. Banneker was not a teacher in ✦ Mathematics is the science and study the usual sense, with a classroom of numbers and how they operate. ✦ full of students. Instead, he taught Astronomy is the science and study of the stars, moon, and planets. mathematics, astronomy, history, 5 Part One 3/20/00 1:48 PM Page 6 6 Part One 3/20/00 1:48 PM Page 7 and other subjects by publishing his knowledge in pamphlets that came out once a year. Born to free black parents, Mary and Robert Banneker, on a farm near the Patapsco River in Baltimore County, Maryland, Benjamin Banneker had deep roots on two continents and a deep understanding of the meaning of freedom. -

Welcome to a Free Reading from Washington History: Magazine of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C

Welcome to a free reading from Washington History: Magazine of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. We hope this essay will help you fill idle hours and provide food for thought and discussion. Benjamin Banneker, the African American mathematician, scientist, and author of almanacs, helped to create Washington, D.C. in 1791. He and his role continue to intrigue Washingtonians more than two centuries later. This essay brings to light the actual records documenting his work on the survey of the District of Columbia that permitted Peter Charles L’Enfant (as he signed his name) to design the city. “Survey of the Federal Territory: Andrew Ellicott and Benjamin Banneker,” by Silvio A. Bedini, first appeared in Washington History Special Bicentennial Issue, vol. 3, no.1 (spring/summer 1991) © Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Access via JSTOR* to the entire run of Washington History and its predecessor, Records of the Columbia Historical Society, is a benefit of membership in the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. at the Membership Plus level. Copies of this and many other back issues of Washington History magazine are available for purchase online through the DC History Center Store: https://dchistory.z2systems.com/np/clients/dchistory/giftstore.jsp ABOUT THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON, D.C. The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a non-profit, 501(c)(3), community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation's capital in order to promote a sense of identity, place and pride in our city and preserve its heritage for future generations. -

MEDIA RELEASE EC250 Asks Visitors to Ellicott City “Where's

MEDIA RELEASE October 16, 2020 History is Coming Alive in Preparation for 2022’s 250th Anniversary Celebration EC250 Asks Visitors to Ellicott City “Where’s George?” MEDIA CONTACTS : Ed Lilley | EC250, Inc. | 410.303.2959 Victoria Goodman | EC250, Inc. | 410.409.2372 ELLICOTT CITY, MARYLAND ‐‐ George Ellicott, a member of Ellicott City’s founding family, is reported to be returning to his old stomping grounds as the 250th anniversary of the town draws near. Visitors to Ellicott City are encouraged to look for George out and about in town this fall on October 24, 31 and November 8 between noon & 4pm. When they spot George, individuals can snap a photo, share it in a Facebook post using the hashtag #IFoundGeorgeinEC and tag @EC250. All photos shared will be entered in a random drawing to win a one‐of‐a‐kind, handmade wooden bank featuring an original ornate metal P.O. Box door from Ellicott City’s old Main Street Post Office. George Ellicott was born in Bucks County Pennsylvania in 1760 to Ellicott City founding father Andrew Ellicott and his wife Elizabeth. George Ellicott married Elizabeth Brooke and together they had 7 children. George moved to Maryland as a teenager and assisted in surveying new roads early in the mill town's development. George Ellicott lived for forty years in a locally quarried granite house built on the east side of the Patapsco River. His home sat on the site of what is now the former Wilkins‐Rogers flour mill. In 1972 the structure was flooded during Tropical Storm Agnes. -

HO-737 Ilchester Mill/Dismal Mill Sites

HO-737 Ilchester Mill/Dismal Mill Sites Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 05-03-2004 - HO 737, llchester Mill/Dismal Mill, ca. 1761, 1833, 1885. Ellicott City vicinity, llchester area, public access. Capsule Summary, page 1. Description: No remains are visible above ground for the mill site. Documentary sources reveal that seven structures stood on the site. The earliest, ca. 1761, was a frame grist mill--called the Dismal Mill--built by Baltimore resident John Cornthwaite; it had a wooden dam secured by stone abutments. Structure number two was a three-story flour mill, most likely of stone construction, with a step gable fronting a gable roof. -

HO-73 Ellicott Mill Original Historic Site

HO-73 Ellicott Mill Original Historic Site Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 05-03-2004 HO 73, Ellicotts Lower Mills Sites, / - 1772, 1809, ca. 1870, 1917-1918. Ellicott City vicinity, llchester area, private access. Capsule Summary, page 1. This document updates the existing Inventory form. Description: Much important evidence has come to light concerning the original appearance and later changes made to Ellicotts Lower Mills. In particular the records of the 1798 Federal Direct Tax, which detail not only the original stone merchant mill, but also the full complex of ten industrial and craft structures, four ancillary buildings, a meeting house, sixteen dwellings and ten residential outbuildings. -

Benjamin Banneker and the Survey of the District of Columbia, 1791

Benjamin Bannekerand the Survey of the District of Columbia, 1791 SILVIO A. BEDINI A he name of Benjamin Banneker, the Afro-American self-taught mathematician and almanac-maker, occurs again and again in the several published accounts of the survey of Washington City begun in 1791, but with conflicting reports of the role which he played. Writers have implied a wide range of involvement, from the keeper of the horses or supervisor of the woodcutters, to the full responsibil- ity of not only the survey of the ten mile square but the design of the city as well. None of these accounts has described the contribution which Banneker actually made. He was, in fact, the scientific assistant of the surveyor, Major Andrew Ellicott, and his work was limited to making astronomical observations and calculations with Ellicott's instruments maintained in the field camp, for the period of the first three months of the project. Banneker has become a familiar figure in Afro-American history and numerous accounts of his life and achievements have been pub- lished during the past century and a half and more. One such bio- graphical sketch, based on earlier published sources, appeared in the Records in 1917.1 Banneker was a free Negro born on November 9, 1731, in Balti- more County, on a farm located within a mile from the present Elli- cott City. His grandmother was a white English-woman who was arrested for a minor offense and sent to Maryland as a transported convict. After serving her period of indenture, she developed a small farm and purchased two slaves, whom she subsequently freed. -

Ellicott Mill of 1809, Then by the Patapsco Mill (Circa 1830'S)

:ormNo. 10-300 . \Q-1 &V UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC XJL EmGCOTT'S MILLS (SITE) HISTORIC DISTRICT AND/OR COMMON OELLA, ELLICQIT CITY LOCATION STREET* NUMBER East and Vfest side of Maryland Route 144, South of Patapsco River Bridge —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT OELLA /w-U i __ VICINITY OF SIXTH STATE CODE COUNTY CODE MARYLAND 24 BALTIMORE 005 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X_DISTRICT —PUBLIC •^-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING<S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^PRIVATE RESIDENCE X —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _|N PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED XINDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME MULTIPLE PRIVATE OWNERS STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE __ VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEos.ETC. BALTIMDRE COUNTY COURTHOUSE STREET & NUMBER WASHINGTON AVENUE CITY. TOWN STATE TOWSON MARYLAND REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE BALTUVDRE COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY HISTORIC BUILDINGS SURVEY DATE 1964-1975 —FEDERAL _STATE ^.COUNTY 2^LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS BALTIMORE HISTORICAL SOCIETY CITY. TOWN STATE MARYLAND CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED XX—ORIGINALSITE XX.GOOD —RUINS XX-ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR XXUNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Elliootts 1 Mills Historic District (Baltimore County) is located on the east bank of the Patapsco River, opposite Ellicott City (Howard County). -

THE ARLINGTON BOUNDARY STONES by June Robinson*

THE ARLINGTON BOUNDARY STONES By June Robinson* In the July heat of Philadelphia, 1787, shortly after the compromise had been reached which allowed members of the Constitutional Convention to continue with their work of writing a constitution, other issues arose which threatened to tear the delegations apart. One of these issues was the location of the seat of government. Where should it be located? Convincing arguments were put forth for New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, Annapolis, and other established cities, as well as for undeveloped areas in a number of other sites. The matter was solved - as were several other controversial issues, by agreeing that the choice would be left up to the Congress of the new government. By September 5, when the Committee of Eleven reported, the following statement was read: 'To exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever over such district (not exceeding ten miles square) as may by cession of particular States and the acceptance of the Legislature become the seat of the Government of the United States ... " 1 Several years later, after the Constitution had been ratified, the first seat of government was designated by the old Congress before it voted itself out of existence. The new Congress would meet in New York, just as it had met. 0 The First Federal Congress was scheduled to assemble the first Wednesday in March, 1789. The House of Representatives was not able to assemble a quorum until April 1; the Senate, until April 6. Congressmen gave weather, bad roads, and poor transportation as excuses. Southerners gave the incon venience of New York as a major reason for the delay.