Proceedings of the 2004 NERR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGENDA 6:00 PM, MONDAY, NOVEMEBR 20Th, 2017 COUNCIL CHAMBERS OCONEE COUNTY ADMINISTRATIVE COMPLEX

AGENDA 6:00 PM, MONDAY, NOVEMEBR 20th, 2017 COUNCIL CHAMBERS OCONEE COUNTY ADMINISTRATIVE COMPLEX 1. Call to Order 2. Invocation by County Council Chaplain 3. Pledge of Allegiance 4. Approval of Minutes a. November 6th, 2017 5. Public Comment for Agenda and Non-Agenda Items (3 minutes) 6. Staff Update 7. Election of Chairman To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 8. Discussion on Planning Commission Schedule for 2018 To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 9. Discussion on the addition of the Traditional Neighborhood Development Zoning District To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 10. Discussion on amending the Vegetative Buffer [To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 11. Discussion on the Comprehensive Plan review To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 12. Old Business [to include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required] 13. New Business [to include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required] 14. Adjourn Anyone wishing to submit written comments to the Planning Commission can send their comments to the Planning Department by mail or by emailing them to the email address below. Please Note: If you would like to receive a copy of the agenda via email please contact our office, or email us at: [email protected]. -

Stream-Temperature Characteristics in Georgia

STREAM-TEMPERATURE CHARACTERISTICS IN GEORGIA By T.R. Dyar and S.J. Alhadeff ______________________________________________________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4203 Prepared in cooperation with GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION Atlanta, Georgia 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 3039 Amwiler Road, Suite 130 Denver Federal Center Peachtree Business Center Box 25286 Atlanta, GA 30360-2824 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and scope . 2 Previous investigations. 2 Station-identification system . 3 Stream-temperature data . 3 Long-term stream-temperature characteristics. 6 Natural stream-temperature characteristics . 7 Regression analysis . 7 Harmonic mean coefficient . 7 Amplitude coefficient. 10 Phase coefficient . 13 Statewide harmonic equation . 13 Examples of estimating natural stream-temperature characteristics . 15 Panther Creek . 15 West Armuchee Creek . 15 Alcovy River . 18 Altamaha River . 18 Summary of stream-temperature characteristics by river basin . 19 Savannah River basin . 19 Ogeechee River basin. 25 Altamaha River basin. 25 Satilla-St Marys River basins. 26 Suwannee-Ochlockonee River basins . 27 Chattahoochee River basin. 27 Flint River basin. 28 Coosa River basin. 29 Tennessee River basin . 31 Selected references. 31 Tabular data . 33 Graphs showing harmonic stream-temperature curves of observed data and statewide harmonic equation for selected stations, figures 14-211 . 51 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing locations of 198 periodic and 22 daily stream-temperature stations, major river basins, and physiographic provinces in Georgia. -

Hiking the Appalachian and Benton Mackaye Trails

10 MILES N # Chattanooga 70 miles Outdoor Adventure: NORTH CAROLINA NORTH 8 Nantahala 68 GEORGIA Gorge Hiking the Appalachian MAP AREA 74 40 miles Asheville co and Benton MacKaye Trails O ee 110 miles R e r Murphy i v 16 Ocoee 64 Benton MacKaye Trail Whitewater Center Appalachian Trail Big Frog 64 Wilderness 69 175 1 Springer Mountain (Trail Copperhill TENNESSEE NORTH CAROLINA Terminus for AT & BMT) GEORGIA GEORGIA McCaysville GEORGIA 75 2 Three Forks 15 Epworth spur 3 Long Creek Falls T 76 o 60 Hiwassee 2 c 2 5 c 129 4 Woody Gap Cohutta o Wilderness S BR Scenic RRa 60 Young F R Harris 288 5 Neels Gap, Walasi-Yi iv e Mineral r Center 14 Blu 2 6 Tesnatee Gap, Richard Mercier Brasstown Russell Scenic Hwy. Orchards F Bald S 64 13 Lake Morganton Blairsville 7 Unicoi Gap Blue 515 17 Ridge old 8 Toccoa River & Swinging Blue 76 Ridge 129 Bridge A s k a 60 9 Wilscot Gap, Hwy 60 R oa 180 Benton TrailMacKaye d 7 10 Shallowford Bridge 12 10 11 Stanley Creek Rd. 9 Vogel Cooper Creek State Park 11 Scenic Area 12 Fall Branch Falls Rich Mtn. 75 Dyer Gap Wilderness 13 515 8 180 5 14 Watson Gap Tocc 6 oa River 348 15 Jacks River Trail 52 BMT Trail Section Distances (miles) (6.0) Springer Mountain - Three Forks 19 Helen (Dally Gap) (1.1) Three Forks - Long Creek Falls 3 60 16 Thunder Rock (8.8) Three Forks - Swinging Bridge FS Ellijay (14.5) Swinging Bridge - Wilscot Gap 58 Suches Campground (7.5) Wilscot Gap - Shallowford Bridge F S Three (33.0) Shallowford Bridge - Dyer Gap 4 Forks 4 75 (24.1) Dyer Gap - US 64 2 2 Main Welcome Center Appalachian Trail -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2014 to 09/30/2014 Francis Marion and Sumter National Forests This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R8 - Southern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Chattooga River Boating - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:11/2014 11/2014 James Knibbs Access Notice of Initiation 07/24/2013 803-561-4078 EA Est. Comment Period Public [email protected] Notice 07/2014 Description: The Forest Service is proposing to establish access points for boaters on the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River within the boundaries of three National Forests (Chattahoochee, Nantahala and Sumter). Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=42568 Location: UNIT - Chattooga River Ranger District, Nantahala Ranger District, Andrew Pickens Ranger District. STATE - Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina. COUNTY - Jackson, Macon, Oconee, Rabun. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Access points for boaters:Nantahala RD - Green Creek; Norton Mill and Bull Pen Bridge; Chattooga River RD - Burrells Ford Bridge; and, Andrew Pickens RD - Lick Log. Southern Region Caves and - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Completed Actual: 06/02/2014 07/2014 Dennis Krusac Mine Closures 404-347-4338 CE [email protected] Description: The purpose of the action is to close caves and mines to minimize the transmission potential of white nose -

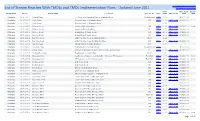

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

Recreational Rock Hounding

Designated Areas On the Nantahala and Pisgah NFs Wilderness (6) – 66,388 ac Wilderness Study Areas (5) • Ellicott Rock – 3,394 ac • Craggy Mountain – 2,380 ac • Joyce Kilmer/Slickrock- 13,562ac • Harper Creek – 7,140 ac • Linville Gorge – 11,786 • Lost Cove – 5,710 ac • Overflow – 3,200 ac • Middle Prong – 7,460 Roan Mountain • Shining Rock – 18,483 • Snowbird – 8,490 ac • Southern Nantahala – 11,703 Experimental Forests (3) Wild and Scenic Rivers (3) • Bent Creek – 5,242 ac • Chattooga • Blue Valley – 1,400 ac • Horsepasture • Coweeta – 5,482 ac • Wilson Creek National Scenic Trail (1) Balds – 3,880 ac • Appalachian Trail– 12,450 ac, approximately 240 miles Whiteside Mountain Roan Mountain – 7,900 ac Research Natural Areas (2) • Walker Cove – 53 Designated areas on the forest • Black Mountain – 1,405 include areas that are nationally Special Interest Areas (40) – 40,787 ac designated (i.e. wilderness, • Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest – 3,840 ac National Historic Area (1) roadless areas) and those that are • Santeetlah Crk Bluffs – 495 ac • Cradle of Forestry – 6,540 ac designated in the current forest • Bonas Defeat Gorge – 305 ac plan with a particular • Bryson Branch – 44 ac Inventoried Roadless Areas (33) – management that differs from • Cole Mountain-Shortoff Mountain – 56 ac 124,000 ac • Cullasaja Gorge – 1,425 ac general forest management. • Bald Mountain – 11,227 ac • Ellicott Rock-Chattooga River – 1,997 ac • Balsam Cone – 10,651 ac Designated areas are generally • Kelsey Track – 256 ac • Barkers Creek (Addition) – 974 ac unsuitable for timber production. • Piney Knob Fork – 32 ac • Bearwallow – 4,112 ac • Scaly Mountain and Catstairs – 130 ac Total designated area is • Big Indian (Addition) – 1,152 ac • Slick Rock – 11 ac • Boteler Peak – 4,215 ac approximately 268,000 acres, • Walking Fern Cove – 19 ac • Cheoah Bald – 7,802 ac ~34% of the total forest. -

Resolved by the Senate and House Of

906 PUBLIC LAW 90-541-0CT. I, 1968 [82 STAT. Public Law 90-541 October 1, 1968 JOINT RESOLUTION [H.J. Res, 1461] Making continuing appropriations for the fiscal year 1969, and for other purposes. Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatimes of tlie United Continuing ap propriations, States of America in Congress assernbled, That clause (c) of section 1969. 102 of the joint resolution of June 29, 1968 (Public Law 90-366), is Ante, p. 475. hereby further amended by striking out "September 30, 1968" and inserting in lieu thereof "October 12, 1968". Approved October 1, 1968. Public Law 90-542 October 2, 1968 AN ACT ------[S. 119] To proYide for a Xational Wild and Scenic Rivers System, and for other purPoses. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Wild and Scenic United States of America in Congress assembled, That (a) this Act Rivers Act. may be cited as the "vVild and Scenic Rivers Act". (b) It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States that certain selected rivers of the Nation which, with their immediate environments, possess outstandin~ly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural, or other similar values, shall be preserved in free-flowing condition, and that they and their immediate environments shall be protected for the benefit and enjoy ment of l?resent and future generations. The Congress declares that the established national policy of dam and other construction at appro priate sections of the rivers of the United States needs to be com plemented by a policy that would preserve other selected rivers or sections thereof m their free-flowing condition to protect the water quality of such rivers and to fulfill other vital national conservation purposes. -

Geologic Controls on the Morphology of the Chattooga River

Geologic Controls on the Morphology of the Chattooga River Scott E. Brame Geological Sciences Clemson University Clemson, SC 29634 and Robert D. Hatcher, Jr. Earth and Planetary Sciences and Science Alliance Center of Excellence University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37996–1410 Abstract The East fork of the Wild and Scenic Chattooga River drains the south side of Whiteside Mountain in North Carolina and flows in a predominant southwesterly direction following the predominant joint direction, and to a much lesser extent the foliation, until it turns sharply to the southeast becoming part of the Savannah River system and flows to the Atlantic Ocean. Paralleling the northeast to southwest trend is the Brevard fault zone and two other river systems, the Chauga River in South Carolina and the Chattahoochee River in Georgia. The Chauga follows a pattern similar to that of the Chattooga, turning sharply to the southeast after flowing predominantly to the southwest from its headwaters. The locations that mark the abrupt turn of the flow of the Chattooga and Chauga Rivers from the southwest to the southeast are likely the result of stream piracy as proposed by Acker and Hatcher. The upper sections of the Chattooga and Chauga represent an extension of the Dahlonega Plateau with a topographic surface that has a maximum elevation of approximately 1600 feet. The 1600’ surface is a piedmont surface at the base of the Blue Ridge. Differential erosion along northeast- and northwest-trending joint sets has exerted a powerful control on the development of the landscape. The northwest-trending joint sets have encouraged headward erosion and breaching of the Dahlonega Plateau surface resulting in stream capture of both the Chattooga and Chauga watersheds by the Savannah River system. -

Outdoor Recreation Plan

SCORP 2014 South Carolina State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan i SOUTH CAROLINA STATE COMPREHENSIVE OUTDOOR RECREATION PLAN (SCORP) 2014 Nikki R. Haley Governor of South Carolina Duane Parrish Director, South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Phil Gaines Director, State Park Service State Liaison Officer South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism 1205 Pendleton Street Columbia, South Carolina 29201 803-734-1658 www.discoversouthcarolina.com www.scprt.com The preparation of this report was financed by the South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks go to the following: Charleston County Park and Recreation Commission James Island County Park, the Lexington County Recreation and Aging Commission Cayce Tennis and Fitness Center, and Greenville County Recreation for the use of meeting facilities for the regional public hearings. Numerous public hearing participants and representatives of the more than 50 agencies and organizations that actively participated in the SCORP planning process, provided current information and data, submitted recommendations and contributed valuable comments and insight for the draft document. The Institute for Public Service and Policy Research, University of South Carolina, for their work on the 2014 South Carolina Outdoor Recreation Plan. Amy Blinson, Alternate State Liaison Officer, S.C. Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism, for her work on the 2014 South Carolina Outdoor Recreation Plan. Perry Baker, Interactive Manager/DiscoverSouthCarolina.com, for valuable assistance with the photos provided for the 2014 South Carolina Outdoor Recreation Plan. The main cover photo of this publication is Hunting Island State Park and the back cover is Table Rock State Park. -

The Savannah River System L STEVENS CR

The upper reaches of the Bald Eagle river cut through Tallulah Gorge. LAKE TOXAWAY MIDDLE FORK The Seneca and Tugaloo Rivers come together near Hartwell, Georgia CASHIERS SAPPHIRE 0AKLAND TOXAWAY R. to form the Savannah River. From that point, the Savannah flows 300 GRIMSHAWES miles southeasterly to the Atlantic Ocean. The Watershed ROCK BOTTOM A ridge of high ground borders Fly fishermen catch trout on the every river system. This ridge Chattooga and Tallulah Rivers, COLLECTING encloses what is called a EASTATOE CR. SATOLAH tributaries of the Savannah in SYSTEM watershed. Beyond the ridge, LAKE Northeast Georgia. all water flows into another river RABUN BALD SUNSET JOCASSEE JOCASSEE system. Just as water in a bowl flows downward to a common MOUNTAIN CITY destination, all rivers, creeks, KEOWEE RIVER streams, ponds, lakes, wetlands SALEM and other types of water bodies TALLULAH R. CLAYTON PICKENS TAMASSEE in a watershed drain into the MOUNTAIN REST WOLF CR. river system. A watershed creates LAKE BURTON TIGER STEKOA CR. a natural community where CHATTOOGA RIVER ARIAIL every living thing has something WHETSTONE TRANSPORTING WILEY EASLEY SYSTEM in common – the source and SEED LAKEMONT SIX MILE LAKE GOLDEN CR. final disposition of their water. LAKE RABUN LONG CREEK LIBERTY CATEECHEE TALLULAH CHAUGA R. WALHALLA LAKE Tributary Network FALLS KEOWEE NORRIS One of the most surprising characteristics TUGALOO WEST UNION SIXMILE CR. DISPERSING LAKE of a river system is the intricate tributary SYSTEM COURTENAY NEWRY CENTRALEIGHTEENMILE CR. network that makes up the collecting YONAH TWELVEMILE CR. system. This detail does not show the TURNERVILLE LAKE RICHLAND UTICA A River System entire network, only a tiny portion of it. -

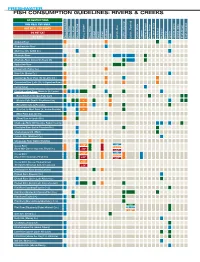

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T.