Book Review.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PCD LAGDO.Pdf

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix – Travail – Patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland ********* *********** MINISTERE DE L’ADMINISTRATION MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL TERRITORIALE ET DE LA ADMINISTRATION DECENTRALISATION AND DECENTRALISATION *********** *********** REGION DU NORD NORTH REGION *********** *********** DEPARTEMENT DE LA BENOUE BENUE DIVISION *********** *********** COMMUNE DE LAGDO LADGO COUNCIL *********** *********** PLAN COMMUNAL DE DEVELOPPEMENT D E L A G D O PLANIFICATION COMMUNALE AVEC L’APPUI DU PNDP juin 2015 Programme National de Développement Participatif (PNDP)-Cellule Régionale de Coordination du Nord -Tél : 22 27 10 70 / 98 49 89 91 – E Mail : [email protected]– Site Web : www.pndp.org g i SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE ......................................................................................................................................................... ii RESUME DU PCD ................................................................................................................................................ vi LISTE DES ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................... vii LISTE DES TABLEAUX ......................................................................................................................................... xii LISTE DES PHOTOS ........................................................................................................................................... xiii LISTE DES CARTES -

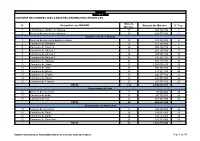

De 40 MINMAP Région Du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES

MINMAP Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine de Garoua 11 847 894 350 3 2 Services déconcentrés régionaux 20 528 977 000 4 Département de la Bénoué 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 283 500 000 6 4 Commune de Barndaké 13 376 238 000 7 5 Commune de Bascheo 16 305 482 770 8 6 Commune de Garoua 1 11 201 187 000 9 7 Commune de Garoua 2 26 498 592 344 10 8 Commune de Garoua 3 22 735 201 727 12 9 Commune de Gashiga 21 353 419 404 14 10 Commune de Lagdo 21 2 026 560 930 16 11 Commune de Pitoa 18 360 777 700 18 12 Commune de Bibémi 18 371 277 700 20 13 Commune de Dembo 11 300 277 700 21 14 Commune de Ngong 12 235 778 000 22 15 Commune de Touroua 15 187 777 700 23 TOTAL 214 6 236 070 975 Département du Faro 16 Services déconcentrés 5 96 500 000 25 17 Commune de Beka 15 230 778 000 25 18 Commune de Poli 22 481 554 000 26 TOTAL 42 808 832 000 Département du Mayo-Louti 19 Services déconcentrés 6 196 000 000 28 20 Commune de Figuil 16 328 512 000 28 21 Commune de Guider 28 534 529 000 30 22 Commune de Mayo Oulo 24 331 278 000 32 TOTAL 74 1 390 319 000 MINMAP / DIVISION DE LA PROGRAMMATION ET DU SUIVI DES MARCHES PUBLICS Page 1 de 40 MINMAP Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés Département du Mayo-Rey 23 Services déconcentrés 7 152 900 000 35 24 Commune de Madingring 14 163 778 000 35 24 Commune de Rey Bouba -

Cameroon : Adamawa, East and North Rgeions

CAMEROON : ADAMAWA, EAST AND NORTH RGEIONS 11° E 12° E 13° E 14° E N 1125° E 16° E Hossere Gaval Mayo Kewe Palpal Dew atan Hossere Mayo Kelvoun Hossere HDossere OuIro M aArday MARE Go mbe Trabahohoy Mayo Bokwa Melendem Vinjegel Kelvoun Pandoual Ourlang Mayo Palia Dam assay Birdif Hossere Hosere Hossere Madama CHARI-BAGUIRMI Mbirdif Zaga Taldam Mubi Hosere Ndoudjem Hossere Mordoy Madama Matalao Hosere Gordom BORNO Matalao Goboum Mou Mayo Mou Baday Korehel Hossere Tongom Ndujem Hossere Seleguere Paha Goboum Hossere Mokoy Diam Ibbi Moukoy Melem lem Doubouvoum Mayo Alouki Mayo Palia Loum as Marma MAYO KANI Mayo Nelma Mayo Zevene Njefi Nelma Dja-Lingo Birdi Harma Mayo Djifi Hosere Galao Hossere Birdi Beli Bili Mandama Galao Bokong Babarkin Deba Madama DabaGalaou Hossere Goudak Hosere Geling Dirtehe Biri Massabey Geling Hosere Hossere Banam Mokorvong Gueleng Goudak Far-North Makirve Dirtcha Hwoli Ts adaksok Gueling Boko Bourwoy Tawan Tawan N 1 Talak Matafal Kouodja Mouga Goudjougoudjou MasabayMassabay Boko Irguilang Bedeve Gimoulounga Bili Douroum Irngileng Mayo Kapta Hakirvia Mougoulounga Hosere Talak Komboum Sobre Bourhoy Mayo Malwey Matafat Hossere Hwoli Hossere Woli Barkao Gande Watchama Guimoulounga Vinde Yola Bourwoy Mokorvong Kapta Hosere Mouga Mouena Mayo Oulo Hossere Bangay Dirbass Dirbas Kousm adouma Malwei Boulou Gandarma Boutouza Mouna Goungourga Mayo Douroum Ouro Saday Djouvoure MAYO DANAY Dum o Bougouma Bangai Houloum Mayo Gottokoun Galbanki Houmbal Moda Goude Tarnbaga Madara Mayo Bozki Bokzi Bangei Holoum Pri TiraHosere Tira -

Forecasts and Dekadal Climate Alerts for the Period 11Th to 20Th July 2021

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix-Travail-Patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland ----------- ----------- OBSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUR NATIONAL OBSERVATORY LES CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES ON CLIMATE CHANGE ----------------- ----------------- DIRECTION GENERALE DIRECTORATE GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- ONACC www.onacc.cm; [email protected]; Tel : (+237) 693 370 504 / 654 392 529 BULLETIN N° 86 Forecasts and Dekadal Climate Alerts for the Period 11th to 20th July 2021 th 11 July 2021 © NOCC July 2021, all rights reserved Supervision Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathe, Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). Production Team (NOCC) Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathe, Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). BATHA Romain Armand Soleil, PhD student and Technical staff, NOCC. ZOUH TEM Isabella, M.Sc. in GIS-Environment and Technical staff, NOCC. NDJELA MBEIH Gaston Evarice, M.Sc. in Economics and Environmental Management. MEYONG Rene Ramses, M.Sc. in Physical Geography (Climatology/Biogeography). ANYE Victorine Ambo, Administrative staff, NOCC. MEKA ZE Philemon Raissa, Administrative staff, NOCC. ELONG Julien Aymar, -

Valorization of Non-Timber Forest Products in Mayo-Rey (North Cameroon) Journal of Applied Biosciences 108: 10491-10499

Tchingsabe et al., J. Appl. Biosci. 2016 Valorization of non-timber forest products in Mayo-Rey (North Cameroon) Journal of Applied Biosciences 108: 10491-10499 ISSN 1997-5902 Valorization of non-timber forest products in Mayo- Rey (North Cameroon) Obadia Tchingsabe* 1, 3 , Arlende Flore Ngomeni1, Pierre Marie Mapongmetsem2, Nwegueh Alfred Bekwake 1, Ronald Noutcheu 3, Siergfried Didier Dibong 3, Mathurin Tchatat 1 and Guidawa Fawa 2 1. The Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (IRAD), Nkolbison, B.P. 2067 Yaoundé, Cameroon 2. Laboratory of Biodiversity and Sustainable Development, University of Ngoundere, B.P. 454 Ngaoundere, Cameroon 3. Laboratory of Biology and Plant Physiology of Organisms of Douala, B.P. 2701 Douala, Cameroon. *1, 3 Corresponding author email: [email protected] Original submitted in on 19 th October 2016. Published online at www.m.elewa.org on 31 st December 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jab.v108i1.2 ABSTRACT Objective: Studies were conducted to characterize the Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) from the locality of Mayo- Rey in the North Region of Cameroon for their subsequent domestication. Methodology and Results: An ethnobotanical survey was conducted among 200 people drawn from four ethnic groups (Laka, Lamé, Peulh and Toupouri). This study has identified 107 plant species including 54 species food (vegetables, fruits and traditional drinks). The species Dioscorea bulbifera , Burnatia sp., Parkia biglobosa , Detarium microcarpum , Adansonia digitata, Vitellaria paradoxa , Ziziphus mauritiana , Ximenia americana and Vitex doniana were identified as major species of this town, due to their socio-economic importance. Plant parts used in the diet are descending fruits (53.70%), seeds (25.92%), leaves (22.22%), tubers (16.66%), the flowers (3.70%) and other (3.7%).Analyses on food uses indicates that 40 respondents use them as recipes involve fruits and 11 use them to prepare sauce. -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Cameroon/2019 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights August 2019 2,300,000 • More than 118,000 people have benefited from UNICEF’s # of children in need of humanitarian assistance humanitarian assistance in the North-West and South-West 4,300,000 regions since January including 15,800 in August. # of people in need (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2019) • The Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) strategy, Displacement established in the South-West region in June, was extended 530,000 into the North-West region in which 1,640 people received # of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the North- WASH kits and Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs) in West and South-West regions (OCHA Displacement Monitoring, July 2019) August. 372,854 # of IDPs and Returnees in the Far-North region • In August, 265,694 children in the Far-North region were (IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix 18, April 2019) vaccinated against poliomyelitis during the final round of 105,923 the vaccination campaign launched following the polio # of Nigerian Refugees in rural areas (UNHCR Fact Sheet, July 2019) outbreak in May. UNICEF Appeal 2019 • During the month of August, 3,087 children received US$ 39.3 million psychosocial support in the Far-North region. UNICEF’s Response with Partners Total funding Funds requirement received Sector Total UNICEF Total available 20% $ 4.5M Target Results* Target Results* Carry-over WASH: People provided with 374,758 33,152 75,000 20,181 $ 3.2 M access to appropriate sanitation 2019 funding Education: Number of boys and requirement: girls (3 to 17 years) affected by 363,300 2,415 217,980 0 $39.3 M crisis receiving learning materials Nutrition**: Number of children Funding gap aged 6-59 months with SAM 60,255 39,727 65,064 40,626 $ 31.6M admitted for treatment Child Protection: Children reached with psychosocial support 563,265 160,423 289,789 87,110 through child friendly/safe spaces C4D: Persons reached with key life- saving & behaviour change 385,000 431,034 messages *Total results are cumulative. -

Cameroon Page 1 of 19

Cameroon Page 1 of 19 Cameroon Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 28, 2005 Cameroon is a republic dominated by a strong presidency. Despite the country's multiparty system of government, the Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (CPDM) has remained in power since the early years of independence. In October, CPDM leader Paul Biya won re-election as President. The primary opposition parties fielded candidates; however, the election was flawed by irregularities, particularly in the voter registration process. The President retains the power to control legislation or to rule by decree. He has used his legislative control to change the Constitution and extend the term lengths of the presidency. The judiciary was subject to significant executive influence and suffered from corruption and inefficiency. The national police (DGSN), the National Intelligence Service (DGRE), the Gendarmerie, the Ministry of Territorial Administration, Military Security, the army, the civilian Minister of Defense, the civilian head of police, and, to a lesser extent, the Presidential Guard are responsible for internal security; the DGSN and Gendarmerie have primary responsibility for law enforcement. The Ministry of Defense, including the Gendarmerie, DGSN, and DRGE, are under an office of the Presidency, resulting in strong presidential control of internal security forces. Although civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces, there were frequent instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of government authority. Members of the security forces continued to commit numerous serious human rights abuses. The majority of the population of approximately 16.3 million resided in rural areas; agriculture accounted for 24 percent of gross domestic product. -

II. CLIMATIC HIGHLIGHTS for the PERIOD 21St to 30Th JANUARY, 2020

OBSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUR Dekadal Bulletin from 21st to 30th January, 2020 LES CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES Bulletin no 33 NATIONAL OBSERVATORY ON CLIMATE CHANGE DIRECTION GENERALE - DIRECTORATE GENERAL ONACC ONACC-NOCC www.onacc.cm; email: [email protected]; Tel (237) 693 370 504 CLIMATE ALERTS AND PROBABLE IMPACTS FOR THE PERIOD 21st to 30th JANUARY, 2020 Supervision NB: It should be noted that this forecast is Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director, National Observatory on Climate Change developed using spatial data from: (ONACC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. - the International Institute for Climate and Ing. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director, National Observatory on Climate Change Society (IRI) of Columbia University, USA; (ONACC). - the National Oceanic and Atmospheric ProductionTeam (ONACC) Administration (NOAA), USA; Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director, ONACC and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. - AccuWeather (American Institution specialized in meteorological forecasts), USA; Eng . FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director, ONACC. BATHA Romain Armand Soleil, Technical staff, ONACC. - the African Centre for Applied Meteorology ZOUH TEM Isabella, MSc in GIS-Environment. for Development (ACMAD). NDJELA MBEIH Gaston Evarice, M.Sc. in Economics and Environmental Management. - Spatial data for Atlantic Ocean Surface MEYONG René Ramsès, M.Sc. in Climatology/Biogeography. Temperature (OST) as well as the intensity of ANYE Victorine Ambo, Administrative staff, ONACC the El-Niño episodes in the Pacific. ELONG Julien Aymar, M.Sc. Business and Environmental law. - ONACC’s research works. I. INTRODUCTION This ten-day alert bulletin n°33 reveals the historical climatic conditions from 1979 to 2018 and climate forecasts developed for the five Agro-ecological zones for the period January 21 to 30, 2020. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Division De La Programmation Et Du Suivi Des Marchés Publics Page 1 De 36 Région Du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES

MINMAP Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine de Garoua 10 1 855 000 000 3 2 Services déconcentrés régionaux 15 728 400 000 4 Département de la Bénoué 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 6 113 030 000 6 4 Commune de Barndaké 12 184 000 000 6 5 Commune de Bascheo 18 378 500 000 8 6 Commune de Bibémi 18 514 195 416 10 7 Commune de Dembo 5 108 000 000 12 8 Commune de Garoua 1 14 294 824 000 12 9 Commune de Garoua 2 12 568 897 796 14 10 Commune de Garoua 3 11 274 080 000 15 11 Commune de Gashiga 5 120 500 000 16 12 Commune de Lagdo 17 393 000 000 18 13 Commune de Ngong 7 205 000 000 19 14 Commune de Pitoa 11 229 000 000 20 15 Commune de Touroua 7 148 124 000 21 TOTAL 143 3 531 151 212 Département du Faro 16 Services déconcentrés départementaux 4 177 000 000 22 17 Commune de Beka 14 237 000 000 22 18 Commune de Poli 16 432 058 220 24 TOTAL 34 846 058 220 Département du Mayo-Louti 19 Services déconcentrés départementaux 9 205 000 000 26 20 Commune de Figuil 11 174 500 000 27 21 Commune de Guider 16 237 600 000 28 22 Commune de Mayo Oulo 24 368 000 000 29 TOTAL 60 985 100 000 Division de la Programmation et du Suivi des Marchés Publics Page 1 de 36 Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés Département du Mayo-Rey 23 Services déconcentrés départementaux 5 147 056 000 32 24 Commune de Madingring 7 106 000 000 32 -

Monthly Humanitarian Situation Report CAMEROON Date: 27Th May 2013

Monthly Humanitarian Situation Report CAMEROON Date: 27th May 2013 Highlights The Health and Nutrition week (SASNIM) was organized in the 10 regions from 26 to 30 April; 1,152,045 children aged 6-59 months received vitamin A and 1,349,937 children aged 12-59 months were dewormed in the Far North and North region. 1,727,391 (101%) children under 5 received Polio drops (OPV), and 38,790 pregnant women received Intermittent Preventive treatment (IPT). A mass screening of acute malnutrition in the North and Far North region was carried out during [the Mother and Child Health and Nutrition Action Week (SASNIM), reaching 90% of children. Out of 1,420,145 children 6-59 months estimated to be covered, 1,288,475 children were enrolled in the mass screening with MUAC, 425,892 in the North region and 862,583 in the Far North. 50,583 MAM cases and 9,269 SAM cases were found and referred to outpatient centres. 10 health districts out of 43 require urgent action. A 10 member delegation led by the UN Foundation team consisting of US Congressional aides and Rotary International visited Garoua - North Region to look at Child Survival and HIV initiatives from April 27 – May 2nd 2013. Following the declaration of state of emergency on May 14 in Nigeria, the actions carried out by Nigerian Government towards the Boko Haram rebels in Maiduguru State (neighbor of Cameroon) may lead to displacement of population from Nigeria to Cameroun. Some Cameroonians living near Nigeria Borno State are moving into Far North region of Cameroon. -

N.Pmruixior Uurrrm DIRECTION DES RESSOURCES RESOURCES HUMAINES

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Rf,PUBLTC OF CAMEROON Paix-Travail-Patrie Peace.Work-Fatherlând MINISTERE DE L'EDUCATION DE MINISTRY OF BASIC EDUCATION BASE GENERAL SECRETARIAT SECRETARIAT Gf,NERAL n.pmruixior uurrrm DIRECTION DES RESSOURCES RESOURCES HUMAINES TROISIEME PROGRAMME DE CONTRACTUALISATION DES INSTITUTEURS AU MINISTERE DE L'EDUCATION DE BASE DEUXIEME OPERATION AU TITRE DE L'EXERCICE 2O2O usrE DEs EcoLEs NECESSTTEUSES (JOB POSTING ) REGION DU NORD N" REGION DEPARTEMENT ARRONDISSEMENT NOM DE L'ECOLE 1 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO ECOLE PUBLIQUE DE BASCHEO 2 NORD BEN OU E BASCHEO EP BANTAYE-BASCH EO 3 NORD BE NOU E BASCHEO EP BARGOUMA 4 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP BOMBOL 5 NORD BENOU E BASCHEO EP DARAM 6 NORD BE NOU E BASCHEO EP DARPATA 7 NORD BE NOU E BASCHEO EP DJALINGO.BELEL 8 NORD BEN OU E BASCHEO EP DJAOURO-MOUSSA 9 NORD BEN OU E BASCHEO EP DJARENGOL 10 NORD BEN OU E BASCHEO EP DORBA 11 NORD B ENOU E BASCHEO EP FOULBERE 72 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP GASSIRE -15 NORD B ENOU E BASCHEO EP HAMAKOUSSOU 14 NORD B ENOU E BASCHEO EP HAMAYEL 15 NORD BENO U E BASCHEO EP HARKOU NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP KATAKO 17 NORD 8 ENOU E BASCHEO EP KATCHATCHIA 18 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP KERZING 19 NORD BENOUE EASCHEO EP KOBOSSI 20 NORD B ENOU E BASCHEO EP LARIA 2t NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP MALKOUROU NORD BENOU E BASCHEO EP MAPOUTKI 23 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP MAYO-OULO-FALI 24 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP MBABI 25 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP MBOULMI 26 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP NARO-KOUBADJE 27 NORD 8 ENOU E BASCHEO EP NASSARAO 28 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP NGOUROU-DABA 29 NORD BENOUE BASCHEO EP