Study of the Economic Impact of Cabotage, and Alternative Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multi-Vessel Drydocking & Repair Contract Employee

FEBRUARYTHE 2015 • VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 2 A LEGACY OF GREATNESS, INNOVATING FOR THE FUTURE MULTI-VESSEL DRYDOCKING & REPAIR CONTRACT FOR US ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS EMPLOYEE ARTICLE “YOUR REPUTATION IS ON THE LINE WITH EVERY TOW” - CAPTAIN MIKE PATTERSON NEW EMPLOYEE FEATURE DIRECTOR OF OPERATIONS PLUS & COMPLIANCE: LINDSAY R. DEW ABOUT US OUR HISTORY FACILITY & EQUIPMENT SHIPYARD ORDER BOOK VENDORS CUSTOMERS EMPLOYEES THE GREAT LAKES TOWING COMPANY & GREAT LAKES SHIPYARD PHOTO: @CAPTAINPT PHOTO: INSTAGRAM PHOTO OF THE MONTH FEBRUARYTHE 2015 • VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 2 A LEGACY OF GREATNESS, INNOVATING FOR THE FUTURE FEATURED SHIPYARD PROJECT 4 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 15 ARTICLES 5 EMPLOYEE 6 SHIPYARD ORDER BOOK TUG CONSTRUCTION 16 ABOUT US BARGE CONSTRUCTION 20 OVERVIEW 7 CUSTOM FABRICATION 22 HISTORY & HERITAGE 7 USCG VESSELS 25 OFFICIALS & DIRECTORS 8 RESEARCH VESSELS 28 LEGACY EMPLOYEES 8 TUGS, FERRIES, LAKERS & MORE 32 BARGE REPAIRS 41 COMPANIES THE GREAT LAKES 9 PARTNERS TOWING COMPANY PARTNERS 45 GREAT LAKES SHIPYARD 10 CUSTOMERS, CHARTERERS 50 FACILITIES & EQUIPMENT 11 & AGENCIES PUERTO RICO TOWING 12 SUPPLIERS, VENDORS 52 & BARGE CO. & SERVICE PROVIDERS TUGZ INTERNATIONAL LLC 12 SOO LINEHANDLING 13 CONTACT US 55 SERVICES, INC. LOYALTY & REWARDS 13 EXPANSION PROJECT 14 COMMUNITY OUTREACH 15 & PHILANTHROPY FEBRUARY 2015 FEATURED PROJECT GREAT LAKES SHIPYARD GREAT LAKES SHIPYARD AWARDED MULTI-VESSEL DRYDOCKING & REPAIR CONTRACT BY US ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS Great Lakes Shipyard has been includes underwater hull cleaning and This will be the first time the Corps’ awarded a repair contract by maintenance, as well as inspection and tugs and barges have been drydocked the United States Army Corps of testing of propulsion systems; overhaul using Great Lakes Shipyard’s 700 Engineers (USACE) Buffalo District for of sea valves and shaft bearings and metric ton capacity Marine Travelift. -

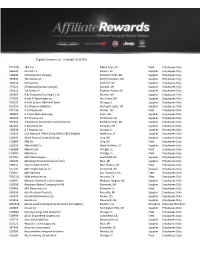

Eligible Company List - Updated 12/1/2016

Eligible Company List - Updated 12/1/2016 S31083 2V Industries Inc Supplier Employees Only S15122 2-Way Communication LLC Supplier Employees Only S10009 3 Dimensional Services Supplier Employees Only S65830 3BL Media LLC Supplier Employees Only S65361 3CSI LLC Supplier Employees Only S66495 3D Sales Inc Supplier Employees Only S69510 3D Systems Supplier Employees Only S65364 3IS Inc Supplier Employees Only S15863 3LK Construction LLC Supplier Employees Only F05233 3M Company Fleet Employees Only S70521 3R Manufacturing Company Supplier Employees Only S61313 7th Sense LP Supplier Employees Only D18911 84 Lumber Company DCC Employees Only S42897 A & S Industrial Coating Co Inc Supplier Employees Only S73205 A and D Technology Inc Supplier Employees Only S57425 A G Manufacturing Supplier Employees Only S86063 A G Simpson Automotive Inc Supplier Employees Only F02130 A G Wassenaar Fleet Employees Only S12115 A M G Industries Inc Supplier Employees Only S19787 A OK Precision Prototype Inc Supplier Employees Only S62637 A Raymond Tinnerman Automotive Inc Supplier Employees Only S82162 A Schulman Inc Supplier Employees Only D80005 A&E Television Networks DCC Employees Only S80904 A.J. Rose Manufacturing Supplier Employees Only S78336 A.T. Kearney, Inc. Supplier Employees Only S34746 A1 Specialized Services Supplier Employees Only S58421 A2MAC1 LLC Supplier Employees Only D60014 AAA East Central DCC Employees & Members S36205 AAA National Office (Only EMPLOYEES Eligible) Supplier Employees Only D60013 AAA Ohio Auto Club DCC Employees & Members -

NCITEC National Center for Intermodal Transportation for Economic Competitiveness

National Center for Intermodal Transportation for Economic Competitiveness Final Report 525 The Impact of Modifying the Jones Act on US Coastal Shipping by Asaf Ashar James R. Amdal UNO Department of Planning and Urban Studies NCITEC National Center for Intermodal Transportation for Economic Competitiveness Supported by: 4101 Gourrier Avenue | Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70808 | (225) 767-9131 | www.ltrc.lsu.edu TECHNICAL REPORT STANDARD PAGE 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA/LA.525 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date The Impact of Modifying the Jones Act on US Coastal June 2014 Shipping 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Asaf Ashar, Professor Research, UNOTI LTRC Project Number: 13-8SS James R. Amdal, Sr. Research Associate, UNOTI State Project Number: 30000766 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. University of New Orleans Department of Planning and Urban Studies 11. Contract or Grant No. 368 Milneburg Hall, 2000 Lakeshore Dr. New Orleans, LA 70148 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Louisiana Department of Transportation and Final Report Development July 2012 – December 2013 P.O. Box 94245 Baton Rouge, LA 70804-9245 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Conducted in Cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovative Technology Administration (RITA), Federal Highway Administration 16. Abstract The study assesses exempt coastal shipping defined as exempted from the US-built stipulation of the Jones Act, operating with functional crews and exempted from Harbor Maintenance Tax (HMT). The study focuses on two research questions: (a) the impact of the US-built exemption on the cost of coastal shipping; and (b) the competitiveness of exempt services. -

Page | 71 CABOTAGE REGIMES and THEIR EFFECTS on STATES

NAUJILJ 9 (1) 2018 CABOTAGE REGIMES AND THEIR EFFECTS ON STATES’ ECONOMY Abstract Countries around the world especially coastal States establish cabotage laws which apply to merchant ships so as to protect the domestic shipping industry from foreign competition by eliminating or limiting the use of foreign vessels in domestic coastal trade. Coastal States’ deep dependence on the seas and its resources remains integral to their economic wellbeing and survival as nations. Due mainly to the importance of maritime trade and the critical role that coastwise and inland waterway transportation play in nations’ economy, these States had always created cabotage laws aimed at protecting the integrity of their coastal waters, preserving domestically owned shipping infrastructure for national security purposes, ensuring safety in congested territorial waters and protecting their domestic economy by restricting the rights of foreign vessels within their territorial waters. The concept of cabotage has however been broadened lately to include air, railway and road transportations. In view of the forgone disquisition, this paper discussed inter alia the basis on which nations anchor their decisions in determining which form of cabotage policy to adopt. The work also investigated into the likely implications of each cabotage regime on the economy of the States adopting it. This work found out that liberalized/relaxed maritime cabotage is the best form of cabotage for both advanced and growing economies and recommended that States should consider it. The work employed doctrinal and analytical research approaches. Keywords: Cabotage, State Security, State Economy, Foreign Vessels, Cabotage Regimes 1. Introduction The term cabotage connotes coastal trading1. It is the transport of goods or passengers between two points/ports within a country’s waterways2. -

Tenth Session of the Statistics Division

STA/10-WP/6 International Civil Aviation Organization 2/10/09 WORKING PAPER TENTH SESSION OF THE STATISTICS DIVISION Montréal, 23 to 27 November 2009 Agenda Item 1: Civil aviation statistics — ICAO classification and definition REVIEW OF DEFINITIONS OF DOMESTIC AND CABOTAGE AIR SERVICES (Presented by the Secretariat) SUMMARY Currently, ICAO uses two different definitions to identify the traffic of domestic flight sectors of international flights; one used by the Statistics Programme, based on the nature of a flight stage, and the other, used for the economic studies on air transport, based on the origin and final destination of a flight (with one or more flight stages). Both definitions have their shortcomings and may affect traffic forecasts produced by ICAO for domestic operations. A similar situation arises with the current inclusion of cabotage services under international operations. After reviewing these issues, the Fourteenth Meeting of the Statistics Panel (STAP/14) agreed to recommend that no changes be made to the current definitions and instructions. Action by the division is in paragraph 5. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 In its activities in the field of air transport economics and statistics, ICAO is currently using two different definitions to identify the domestic services of an air carrier. The first one used by the Statistics Programme has been reaffirmed and clarified during Ninth Meeting of the Statistics Division (STA/9) and it is the one currently shown in the Air Transport Reporting Forms. The second one is being used by the Secretariat in the studies on international airline operating economics which have been carried out since 1976 and in pursuance of Assembly Resolution A36-15, Appendix G (reproduced in Appendix A). -

2010 Top 100 For-Hire

Europe: 1,052,045 Class 8 Luxembourg: 13,629 HCVs China: United States: 2,447 Concrete Mixers 6,692,703 Class 6–8 VIO 2010 April Reg Kansas City: • 82.1% cash 1,277 Class 8, 2005–2010 YM, purchases Freightliners • 17.9% loans Wayne County, MI: Chengdu City: 114,965 Commercial Pickups 321 Concrete Mixers Better Decisions. No Boundaries. The level of geography you want at the level of detail you need. When it comes to understanding which commercial vehicles are in your markets, having the world’s best data in-hand is crucial. Our data-driven solutions for the commercial vehicle industry help you maximize market share, identify emerging market trends, optimize inventory and target your best prospects – locally, globally or somewhere in between. Data-Driven Solutions for the Global Commercial Vehicle Industry www.polk.com/commercialvehicle A Word From the Publisher he headline for the 2010 TRANSPORT TOP- hire carriers are becoming more deeply involved in ICS’ Top 100 For-Hire Carriers was this: managing the movement of freight across many dif- “The Recovery Appears to Take Hold.” ferent modes and to and from many different places And while some trucking companies have in the world. reacted to positive economic news by ex- Still, it’s important to remember that over-the-road Tpanding the size of their fleets, many of the largest for- trucking is not going to disappear, or even shrink in hire carriers are taking a different approach — size. keeping a lid on the number of tractors and trailers American Trucking Associations said it expects rail while shifting the focus of their operations from long- intermodal tonnage will rise 83% to 253.1 million tons haul freight movement to local and regional distribu- in 2021 from 138.6 million tons in 2009. -

Code-Share Agreements: a Developing Trend in U.S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Indiana Law Journal Volume 72 | Issue 2 Article 12 Spring 1997 Code-Share Agreements: A Developing Trend in U.S. Bilateral Aviation Negotiations Robert F. Barron II Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Transportation Law Commons Recommended Citation Barron, Robert F. II (1997) "Code-Share Agreements: A Developing Trend in U.S. Bilateral Aviation Negotiations," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 72 : Iss. 2 , Article 12. Available at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol72/iss2/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Code-Share Agreements: A Developing Trend in U.S. Bilateral Aviation Negotiations ROBERT F. BARRON II* INTRODUCTION Consumers who intend to travel internationally in 1996 and who will originate their journey from interior U.S. cities may be surprised to discover that they are flying on an airline other than the one they thought they booked. Indeed, in accordance with current government regulation of the airline industry, literally thousands of consumers each day find themselves flying on a carrier different from the one indicated on their airline tickets. This is not an aberration-no last minute flight cancellations; no flight protections on another carrier made in the best interest of the consumer. -

Eligible Company List - Updated 1/21/2021

Eligible Company List - Updated 1/21/2021 F011RQ 18 K Inc Eighty Four, PA Fleet Employees Only S66234 2A USA Inc Auburn, AL Supplier Employees Only S10009 3 Dimensional Services Rochester Hills, MI Supplier Employees Only S65830 3BL Media LLC North Hampton, MA Supplier Employees Only S69510 3D Systems Rock Hill, SC Supplier Employees Only S70521 3R Manufacturing Company Goodell, MI Supplier Employees Only S61313 7th Sense LP Bingham Farms, MI Supplier Employees Only S42897 A & S Industrial Coating Co Inc Warren, MI Supplier Employees Only S73205 A and D Technology Inc Ann Arbor, MI Supplier Employees Only S38187 A Finkl & Sons DBA Finkl Steel Chicago, IL Supplier Employees Only S01250 A G Simpson (USA) Inc Sterling Heights, MI Supplier Employees Only F02130 A G Wassenaar Denver, CO Fleet Employees Only S80904 A J Rose Manufacturing Avon, OH Supplier Employees Only S64720 A P Plasman Inc Fort Payne, AL Supplier Employees Only S62637 A Raymond Tinnerman Automotive Inc Rochester Hills, MI Supplier Employees Only S82162 A Schulman Inc Fairlawn, OH Supplier Employees Only S78336 A T Kearney Inc Chicago, IL Supplier Employees Only S36205 AAA National Office (Only EMPLOYEES Eligible) Heathrow, FL Supplier Employees Only S14541 Aarell Process Controls Group Troy, MI Supplier Employees Only F05894 ABB Inc Cary, NC Fleet Employees Only S10035 Abbott Ball Co West Hartford, CT Supplier Employees Only F66984 Abbott Labs Chicago, IL Fleet Employees Only FOOF92 AbbVie Inc Chicago, IL Fleet Employees Only S57205 ABC Technologies Southfield, MI Supplier -

Headquarters

Headquarters Northeast Florida Company Name Company Description Type of Headquarters Employees Florida Blue Health Insurance State Headquarters Regional 5,700 Southeastern Grocers Corporate HQ & Grocery Distribution Center Corporate 5,700 GATE Petroleum Company Petroleum Products Corporate Headquarters Corporate 3,000 CSX Corporation Railroad Corporate Headquarters Corporate 2,900 AT&T Telecommunications Regional Headquarters Regional 2,600 Brooks Rehabilitation Medical Rehabilitation Corporate 2,240 Black Knight Mortgage software development Corporate 2,120 Newfold Web Designers and Online Marketing Corporate 2,000 One Call Workers Compensation Services Corporate 1,970 Johnson & Johnson Vision Contact lens manufacturing Division 1,800 Fanatics E-Commerce Retailer Corporate 1,700 FIS Banking Services Software Provider Corporate 1,500 Wells Fargo Banking Regional 1,450 VyStar Credit Union Credit Union Corporate 1,410 TIAA Bank Banking and Mortgage Services Corporate 1,400 GuideWell Medicare administration Corporate 1,300 Miller Electric Company Electrical Contractors Corporate 1,300 Crowley Maritime Corporation Marine Transportation & Logistics Corporate 1,200 Fidelity National Financial Title Insurance Company Corporate 1,168 Citizens Property Insurance Corporation Insurance Corporate 1,040 Landstar System Inc. Transportation Logistics Corporate 1,000 McKesson Medical-Surgical Medical Supplies Provider to the Physician Market Division 1,000 Medtronic Inc. Surgical Products Manufacturer Division 900 06/2021 jaxusa.org BAKER CLAY DUVAL -

Regulatory Reform in the Civil Aviation Sector

OECD REVIEWS OF REGULATORY REFORM REGULATORY REFORM IN FRANCE REGULATORY REFORM IN THE CIVIL AVIATION SECTOR ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT © OECD (2004). All rights reserved. 1 ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention signed in Paris on 14th December 1960, and which came into force on 30th September 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shall promote policies designed: • to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in Member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy; • to contribute to sound economic expansion in Member as well as non-member countries in the process of economic development; and • to contribute to the expansion of world trade on a multilateral, non-discriminatory basis in accordance with international obligations. The original Member countries of the OECD are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The following countries became Members subsequently through accession at the dates indicated hereafter: Japan (28th April 1964), Finland (28th January 1969), Australia (7th June 1971), New Zealand (29th May 1973), Mexico (18th May 1994), the Czech Republic (21st December 1995), Hungary (7th May 1996), Poland (22nd November 1996), Korea (12th December 1996) and the Slovak Republic (14th December 2000). The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD (Article 13 of the OECD Convention). Publié en français sous le titre : La réforme de la réglementation dans le secteur de l’aviation civile © OECD 2004. -

US-EU Air Transport: Open Skies but Still Not Open Transatlantic Air Services.”

“US-EU Air Transport: Open Skies But Still Not Open Transatlantic Air Services.” Julia Anna Hetlof Institute of Air and Space Law, McGill University, Montreal August 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of LL.M in Air and Space Law. © Julia Hetlof, 2009 Table of Contents Acknowledgments Abstract/Resume Bibliography TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................1 PART 1: DEREGULATION AND LIBERALIZATION OF AIR TRANSPORT REGIMES IN THE UNITED STATES AND EUROPEAN UNION............................4 I. EVOLUTION OF U.S. AIR TRANSPORTATION REGIME: REGULATION, DEREGULATION AND THE PRESENT. ….........................................................5 1. 1938-1978 Era of Governmental Regulation.................................................5 2. 1978 Deregulation of U.S. Domestic Airline Industry..................................8 3. Post-Deregulation Airline Industry Outlook...............................................10 4. Re-regulation or other proposals for Change?............................................12 II. LIBERALIZATION OF AIR TRANSPORTATION REGIME IN THE EUROPEAN UNION............................................................................................15 1. Introduction/History......................................................................................15 2. Liberalization of European Air Transport Market: Three Packages.......16 2.1 First Package (1987)............................................................................16 -

The Impact of International Air Service Liberalisation on Chile

The Impact of International Air Service Liberalisation on Chile Prepared by InterVISTAS-EU Consulting Inc. July 2009 LIBERALISATION REPORT The Impact of International Air Service Liberalisation on Chile Prepared by InterVISTAS-EU Consulting Inc. July 2009 LIBERALISATION REPORT Impact of International Air Service Liberalisation on Chile i Executive Summary At the invitation of IATA, representatives of 14 nation states and the EU met at the Agenda for Freedom Summit in Istanbul on the 25th and 26th of October 2008 to discuss the further liberalisation of the aviation industry. The participants agreed that further liberalisation of the international aviation market was generally desirable, bringing benefits to the aviation industry, to consumers and to the wider economy. In doing so, the participants were also mindful of issues around international relations, sovereignty, infrastructure capacity, developing nations, fairness and labour interests. None of these issues were considered insurmountable and to explore the effects of further liberalisation the participants asked IATA to undertake studies on 12 countries to examine the impact of air service agreement (ASA) liberalisation on traffic levels, employment, economic growth, tourism, passengers and national airlines. IATA commissioned InterVISTAS-EU Consulting Inc. (InterVISTAS) to undertake the 12 country studies. The aim of the studies was to investigate two forms of liberalisation: market access (i.e., liberalising ASA arrangements) and foreign ownership and control.1 This report documents the analysis undertaken to examine the impact of liberalisation on Chile.2 History of Air Service Agreements and Ownership and Control Restrictions Since World War II, international air services between countries have operated under the terms of bilateral air service agreements (ASAs) negotiated between the two countries.