Code-Share Agreements: a Developing Trend in U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page | 71 CABOTAGE REGIMES and THEIR EFFECTS on STATES

NAUJILJ 9 (1) 2018 CABOTAGE REGIMES AND THEIR EFFECTS ON STATES’ ECONOMY Abstract Countries around the world especially coastal States establish cabotage laws which apply to merchant ships so as to protect the domestic shipping industry from foreign competition by eliminating or limiting the use of foreign vessels in domestic coastal trade. Coastal States’ deep dependence on the seas and its resources remains integral to their economic wellbeing and survival as nations. Due mainly to the importance of maritime trade and the critical role that coastwise and inland waterway transportation play in nations’ economy, these States had always created cabotage laws aimed at protecting the integrity of their coastal waters, preserving domestically owned shipping infrastructure for national security purposes, ensuring safety in congested territorial waters and protecting their domestic economy by restricting the rights of foreign vessels within their territorial waters. The concept of cabotage has however been broadened lately to include air, railway and road transportations. In view of the forgone disquisition, this paper discussed inter alia the basis on which nations anchor their decisions in determining which form of cabotage policy to adopt. The work also investigated into the likely implications of each cabotage regime on the economy of the States adopting it. This work found out that liberalized/relaxed maritime cabotage is the best form of cabotage for both advanced and growing economies and recommended that States should consider it. The work employed doctrinal and analytical research approaches. Keywords: Cabotage, State Security, State Economy, Foreign Vessels, Cabotage Regimes 1. Introduction The term cabotage connotes coastal trading1. It is the transport of goods or passengers between two points/ports within a country’s waterways2. -

Tenth Session of the Statistics Division

STA/10-WP/6 International Civil Aviation Organization 2/10/09 WORKING PAPER TENTH SESSION OF THE STATISTICS DIVISION Montréal, 23 to 27 November 2009 Agenda Item 1: Civil aviation statistics — ICAO classification and definition REVIEW OF DEFINITIONS OF DOMESTIC AND CABOTAGE AIR SERVICES (Presented by the Secretariat) SUMMARY Currently, ICAO uses two different definitions to identify the traffic of domestic flight sectors of international flights; one used by the Statistics Programme, based on the nature of a flight stage, and the other, used for the economic studies on air transport, based on the origin and final destination of a flight (with one or more flight stages). Both definitions have their shortcomings and may affect traffic forecasts produced by ICAO for domestic operations. A similar situation arises with the current inclusion of cabotage services under international operations. After reviewing these issues, the Fourteenth Meeting of the Statistics Panel (STAP/14) agreed to recommend that no changes be made to the current definitions and instructions. Action by the division is in paragraph 5. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 In its activities in the field of air transport economics and statistics, ICAO is currently using two different definitions to identify the domestic services of an air carrier. The first one used by the Statistics Programme has been reaffirmed and clarified during Ninth Meeting of the Statistics Division (STA/9) and it is the one currently shown in the Air Transport Reporting Forms. The second one is being used by the Secretariat in the studies on international airline operating economics which have been carried out since 1976 and in pursuance of Assembly Resolution A36-15, Appendix G (reproduced in Appendix A). -

Regulatory Reform in the Civil Aviation Sector

OECD REVIEWS OF REGULATORY REFORM REGULATORY REFORM IN FRANCE REGULATORY REFORM IN THE CIVIL AVIATION SECTOR ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT © OECD (2004). All rights reserved. 1 ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention signed in Paris on 14th December 1960, and which came into force on 30th September 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shall promote policies designed: • to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in Member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy; • to contribute to sound economic expansion in Member as well as non-member countries in the process of economic development; and • to contribute to the expansion of world trade on a multilateral, non-discriminatory basis in accordance with international obligations. The original Member countries of the OECD are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The following countries became Members subsequently through accession at the dates indicated hereafter: Japan (28th April 1964), Finland (28th January 1969), Australia (7th June 1971), New Zealand (29th May 1973), Mexico (18th May 1994), the Czech Republic (21st December 1995), Hungary (7th May 1996), Poland (22nd November 1996), Korea (12th December 1996) and the Slovak Republic (14th December 2000). The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD (Article 13 of the OECD Convention). Publié en français sous le titre : La réforme de la réglementation dans le secteur de l’aviation civile © OECD 2004. -

US-EU Air Transport: Open Skies but Still Not Open Transatlantic Air Services.”

“US-EU Air Transport: Open Skies But Still Not Open Transatlantic Air Services.” Julia Anna Hetlof Institute of Air and Space Law, McGill University, Montreal August 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of LL.M in Air and Space Law. © Julia Hetlof, 2009 Table of Contents Acknowledgments Abstract/Resume Bibliography TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................1 PART 1: DEREGULATION AND LIBERALIZATION OF AIR TRANSPORT REGIMES IN THE UNITED STATES AND EUROPEAN UNION............................4 I. EVOLUTION OF U.S. AIR TRANSPORTATION REGIME: REGULATION, DEREGULATION AND THE PRESENT. ….........................................................5 1. 1938-1978 Era of Governmental Regulation.................................................5 2. 1978 Deregulation of U.S. Domestic Airline Industry..................................8 3. Post-Deregulation Airline Industry Outlook...............................................10 4. Re-regulation or other proposals for Change?............................................12 II. LIBERALIZATION OF AIR TRANSPORTATION REGIME IN THE EUROPEAN UNION............................................................................................15 1. Introduction/History......................................................................................15 2. Liberalization of European Air Transport Market: Three Packages.......16 2.1 First Package (1987)............................................................................16 -

The Impact of International Air Service Liberalisation on Chile

The Impact of International Air Service Liberalisation on Chile Prepared by InterVISTAS-EU Consulting Inc. July 2009 LIBERALISATION REPORT The Impact of International Air Service Liberalisation on Chile Prepared by InterVISTAS-EU Consulting Inc. July 2009 LIBERALISATION REPORT Impact of International Air Service Liberalisation on Chile i Executive Summary At the invitation of IATA, representatives of 14 nation states and the EU met at the Agenda for Freedom Summit in Istanbul on the 25th and 26th of October 2008 to discuss the further liberalisation of the aviation industry. The participants agreed that further liberalisation of the international aviation market was generally desirable, bringing benefits to the aviation industry, to consumers and to the wider economy. In doing so, the participants were also mindful of issues around international relations, sovereignty, infrastructure capacity, developing nations, fairness and labour interests. None of these issues were considered insurmountable and to explore the effects of further liberalisation the participants asked IATA to undertake studies on 12 countries to examine the impact of air service agreement (ASA) liberalisation on traffic levels, employment, economic growth, tourism, passengers and national airlines. IATA commissioned InterVISTAS-EU Consulting Inc. (InterVISTAS) to undertake the 12 country studies. The aim of the studies was to investigate two forms of liberalisation: market access (i.e., liberalising ASA arrangements) and foreign ownership and control.1 This report documents the analysis undertaken to examine the impact of liberalisation on Chile.2 History of Air Service Agreements and Ownership and Control Restrictions Since World War II, international air services between countries have operated under the terms of bilateral air service agreements (ASAs) negotiated between the two countries. -

Australian and International Pilots Association

18 May 2015 General Manager Small Business, Competition and Consumer Policy Division The Treasury Langton Crescent PARKES ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] Dear Mr Dolman, COMMENTS ON THE COMPETITION POLICY REVIEW FINAL REPORT The Australian & International Pilots Association (AIPA) is the largest Association of professional airline pilots in Australia. We represent nearly all Qantas pilots and a significant percentage of pilots flying for the Qantas subsidiaries (including Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd). AIPA represents over 2,100 professional airline transport category flight crew and we are a key member of the International Federation of Airline Pilot Associations (IFALPA) which represents over 100,000 pilots in 100 countries. From the outset, AIPA would like to acknowledge the complexity and breadth of the task that Professor Harper and his team undertook and congratulate the Panel on what we believe to be an exceptional achievement. We also accept and understand that the timeline for the Review was never going to provide the time and space for the Panel to fully inform themselves on the complexities of every suggestion or proposal put to them by respondents to the Review. Nonetheless, we are concerned that, regardless of whatever external constraints may have pragmatically required a very superficial coverage of a very complex space, both the public and the Government may not recognise those inherent limitations in some of the Panel’s recommendations. We previously advised the Panel that they may well benefit from referring to a very recent contribution to the OECD1 (which AIPA understands was provided by the ACCC) that reflects the status quo for airline competition in Australia as best we understand it. -

International Air Service Controversies: Frequently Asked Questions

International Air Service Controversies: Frequently Asked Questions Rachel Y. Tang Analyst in Transportation and Industry May 4, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44016 International Air Service Controversies: Frequently Asked Questions Summary “Open skies” agreements are a form of international civil air service agreement that facilitates international aviation in a deregulated environment. They eliminate government involvement in airline decisionmaking about international routes, capacity, and prices. Since 1992, the United States has reached 114 open skies agreements governing international air passenger and air freight services. There are two ongoing controversies that are related to open skies agreements. One controversy involves some U.S. network airlines’ and labor unions’ opposition to the expansion of three fast- growing airlines based in the Persian Gulf region—Emirates Airline, Etihad Airways, and Qatar Airways. The U.S. carriers allege the subsidies and support that these three Persian Gulf carriers purportedly receive from their government owners contravene fair competitive practices requirements of their home countries’ open skies agreements with the United States. The U.S. carriers have urged the Administration to freeze the number of flights Gulf carriers operate to the United States and to renegotiate the open skies accords with Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Similar protests have occurred in Europe, initiated by Lufthansa Group and Air France-KLM, and organized labor. The other controversy concerns Norwegian Air International (NAI), an airline that is registered in Ireland and plans to operate transatlantic flights to U.S. destinations. NAI’s application has met strong opposition from labor groups and some airlines that allege that NAI violates a provision of the U.S.-EU open skies agreement that governs labor standards. -

AIR TRAFFIC RIGHTS: Deregulation and Liberalization

AIR TRAFFIC RIGHTS: Deregulation and Liberalization Professor Dr. Paul Stephen Dempsey Director, Institute of Air & Space Law McGill University Copyright © 2015 by Paul Stephen Dempsey The Chicago Convention . Article 1 recognizes that each State enjoys complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory. Article 5 gives non-scheduled flights 1st and 2nd Freedom rights, but restricts carriage for compensation on 3rd and 4th Freedoms to “such regulations, conditions or limitations” as the underlying State deems desirable. Article 6 provides that no scheduled flight my operate over or into the territory of a State without its permission, and pursuant to any terms or conditions thereon. The Chicago Conference produced two multilateral documents to exchange such rights – the Transit Agreement (exchanging First and Second Freedom rights), and the Transport Agreement (exchanging the first Five Freedoms). The former has been widely adopted, while the latter has received few ratifications. First Freedom The civil aircraft of one State has the right to fly over the territory of another State without landing, provided the overflown State is notified in advance and approval is given. Second Freedom A civil aircraft of one State has the right to land in another State for technical reasons, such as refueling or maintenance, without offering any commercial service to or from that point. The First and Second Freedoms were multilaterally exchanged in the Transit Agreement concluded at the Chicago Conference in 1944. 126 States have ratified the Transit Agreement. However, several large States have not ratified the Transit Agreement, including the Russian Federation, Canada, China, Brazil, and Indonesia. -

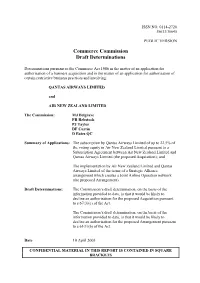

Commerce Commission Draft Determinations

ISSN NO. 0114-2720 J5633/J5645 PUBLIC VERSION Commerce Commission Draft Determinations Determinations pursuant to the Commerce Act 1986 in the matter of an application for authorisation of a business acquisition and in the matter of an application for authorisation of certain restrictive business practices and involving: QANTAS AIRWAYS LIMITED and AIR NEW ZEALAND LIMITED The Commission: MJ Belgrave PR Rebstock PJ Taylor DF Curtin D Bates QC Summary of Applications: The subscription by Qantas Airways Limited of up to 22.5% of the voting equity in Air New Zealand Limited pursuant to a Subscription Agreement between Air New Zealand Limited and Qantas Airways Limited (the proposed Acquisition); and The implementation by Air New Zealand Limited and Qantas Airways Limited of the terms of a Strategic Alliance arrangement which creates a Joint Airline Operation network (the proposed Arrangement) Draft Determinations: The Commission’s draft determination, on the basis of the information provided to date, is that it would be likely to decline an authorisation for the proposed Acquisition pursuant to s 67(3)(c) of the Act. The Commission’s draft determination, on the basis of the information provided to date, is that it would be likely to decline an authorisation for the proposed Arrangement pursuant to s 61(1)(b) of the Act. Date 10 April 2003 CONFIDENTIAL MATERIAL IN THIS REPORT IS CONTAINED IN SQUARE BRACKETS CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................ 9 Proposed -

The Ownership and Control Requirement in US

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 66 | Issue 2 Article 6 2001 The Ownership and Control Requirement in U.S. and European Union Air Law and U.S. Maritime Law - Policy; Consideration; Comparison Kirsten Bohmann Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Kirsten Bohmann, The Ownership and Control Requirement in U.S. and European Union Air Law and U.S. Maritime Law - Policy; Consideration; Comparison, 66 J. Air L. & Com. 689 (2001) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol66/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL REQUIREMENT IN U.S. AND EUROPEAN UNION AIR LAW AND U.S. MARITIME LAW-POLICY; CONSIDERATION; COMPARISON KIRSTEN BOHMANN* I. INTRODUCTION T HE NATURE of international trade has significantly changed over the last decades. Government-imposed barri- ers to the free trade of goods and services have been reduced, and that has contributed to the development of a unified global market economy. Considering the increasing importance of ser- vices, many nations are trying to enhance their participation in the free trade of services, particularly in the international air services market. For decades, many countries owned and controlled their na- tional airlines, mainly for reasons of national prestige and secur- ity. They viewed their "national air carriers" as vital to their national economic interests and, consequently, they supported and sustained their aviation industry. -

The Bermuda Agreement Revisited: a Look at the Past, Present and Future of Bilateral Air Transport Agreements Barry R

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 41 | Issue 3 Article 3 1975 The Bermuda Agreement Revisited: A Look at the Past, Present and Future of Bilateral Air Transport Agreements Barry R. Diamond Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Barry R. Diamond, The Bermuda Agreement Revisited: A Look at the Past, Present and Future of Bilateral Air Transport Agreements, 41 J. Air L. & Com. 419 (1975) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol41/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE BERMUDA AGREEMENT REVISITED: A LOOK AT THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF BILATERAL AIR TRANSPORT AGREEMENTS BARRY R. DIAMOND* INTRODUCTION THE BERMUDA Agreement' between the United States and the United Kingdom has governed both countries' policy con- cerning the exchange of international commercial air traffic rights since its negotiation in 1946. The Bermuda Agreement operates, in the larger context of bilateral air transport agreements (BATA's),' and has been present in international civil aviation since the period prior to World War I. The aim of this article is to examine the operation of the Bermuda Agreement, past and present, and to venture some predictions as to its future role in international air transportation. To achieve this aim the following approach has been adopted. First, the general subject of BATA's is considered, with attention being focused on their background, elements, types, and manner of negotiation. -

EU External Aviation Policy

Briefing May 2016 EU external aviation policy SUMMARY The 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation ('Chicago Convention') is the chief regulatory framework for international civil aviation, but also the most important primary source of public international aviation law and the umbrella under which bilateral air service agreements have been developed. While in the early days bilateral air service agreements between states were quite restrictive, having been written with the intention of protecting their respective flag carriers, in the early 1990s the United States proposed a more flexible model of bilateral air services agreements, the so-called 'Open Skies' agreements. Challenged on the grounds that some of their provisions were not in conformity with Community law, these agreements led in 2002 to the European Court of Justice's 'Open Skies' judgments. These judgments triggered the development of an EU external aviation policy, which has led to the conclusion of over 50 horizontal agreements as well as to the negotiation and conclusion of comprehensive EU agreements with some neighboring countries and key trading partners. To tackle the challenges currently facing international air transport and, in particular, the increased competition from third countries, the Commission adopted in December 2015 a new aviation strategy for Europe that places great emphasis on the external dimension. The European Parliament is now examining this strategy. In this briefing: The international civil aviation framework Development of the EU's external