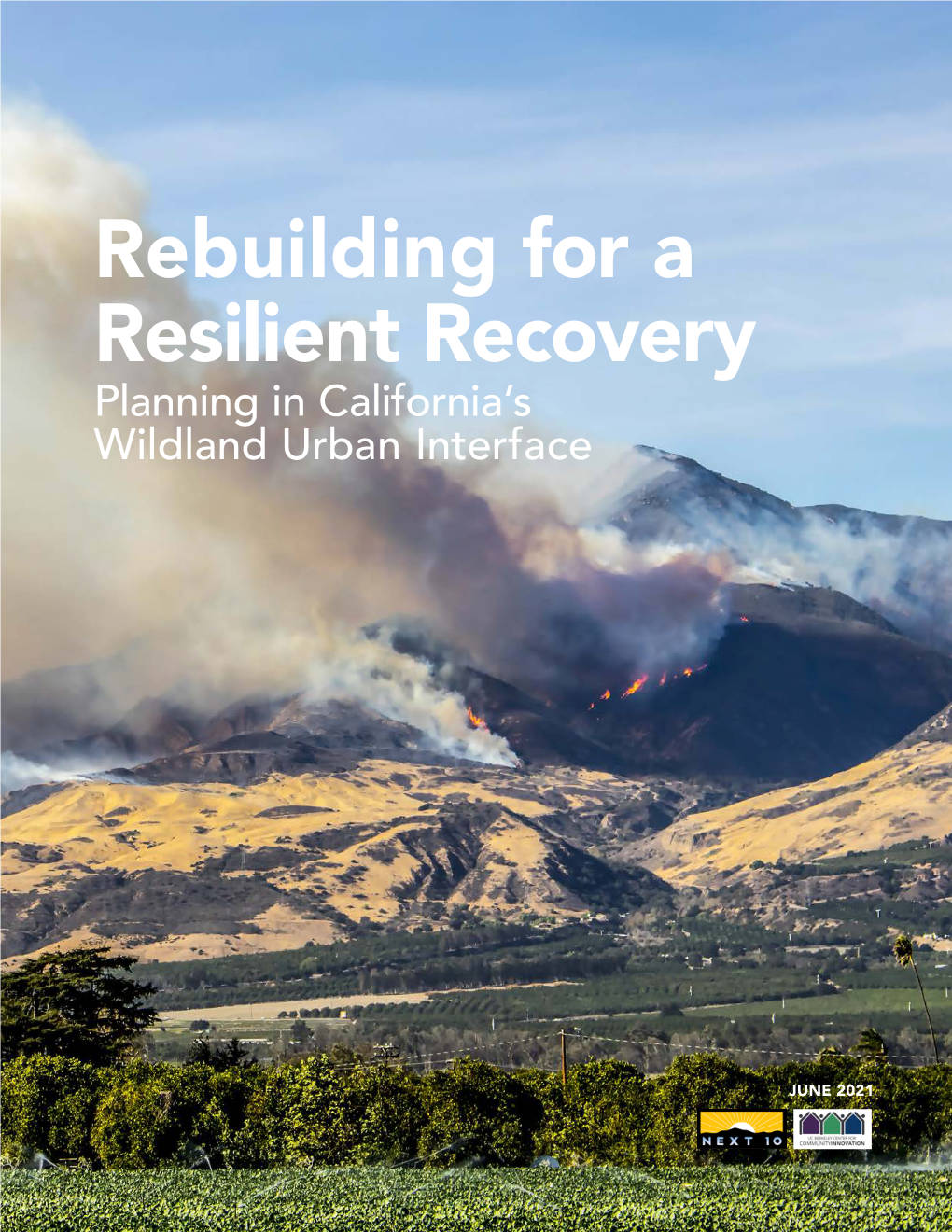

Rebuilding for a Resilient Recovery Planning in California’S Wildland Urban Interface

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2020 California Wildfires Helping Handbook

HELPING HANDBOOK FOR INDIVIDUALS AND SMALL BUSINESSES AFFECTED BY THE SEPTEMBER 2020 CALIFORNIA WILDFIRES This handbook provides an overview of some issues that individuals, families, and small businesses may face as a result of the fires that broke out in California starting on September 4, 2020. While fires have occurred throughout the state in 2020, this handbook focuses particularly on Fresno, Los Angeles, Madera, Mendocino, Napa, San Bernardino, San Diego, Shasta, Siskiyou, and Sonoma counties because, as of the time of this publication, these were the counties covered by the federal government’s Major Disaster Declaration, DR-4569 (declared on October 16, 2020 and later amended), which triggered certain assistance to individuals. Please note, unless otherwise indicated, this handbook is only current through October 19, 2020. By the time you read this material, the federal, state, and county governments may have enacted additional measures to assist victims of the fire that may affect some of the information we present. This handbook will not answer all of your questions. It is designed to set out some of the issues you may have to consider, to help you understand the basics about each issue, and to point you in the right direction for help. Much of the information in this handbook is general, and you may have to contact government officials, or local aid organizations, to obtain more specific information about issues in your particular area. You may feel overwhelmed when considering the legal issues you face, and you may find it helpful or even necessary to obtain an attorney’s assistance. -

From Heavy Metals to COVID-19, Wildfire Smoke Is More Dangerous Than You Think 26 July 2021, by Hayley Smith

From heavy metals to COVID-19, wildfire smoke is more dangerous than you think 26 July 2021, by Hayley Smith fire was particularly noxious because it contained particulates from burned homes as well as vegetation—something officials fear will become more common as home-building pushes farther into the state's wildlands. Another study linked wildfire smoke to an increased risk of contracting COVID-19. The findings indicate that as fire season ramps up, the dangers of respiratory illness and other serious side effects from smoke loom nearly as large as the flames. The 2018 Camp fire was the deadliest wildfire on Credit: CC0 Public Domain record in California. At least 85 people died, and nearly 19,000 buildings were destroyed, mostly in Paradise. When Erin Babnik awoke on the morning of Nov. 8, The fire also generated a massive plume of heavy 2018, in Paradise, California, she thought the smoke that spewed dangerously high levels of reddish glow outside was a hazy sunrise. pollution into the air for about two weeks, according to a study released this month by the California Air But the faint light soon gave way to darkness as Resources Board. smoke from the burgeoning Camp fire rolled in. Researchers examined data from air filters and "The whole sky turned completely black, and there toxic monitors to determine that smoke from the fire were embers flying around," Babnik recalled. "I was in many ways more harmful than that of three remember it smelling horrible." other large fires that burned mostly vegetation that year—the Carr fire, the Mendocino Complex fire and She hastily evacuated to nearby Chico with little the Ferguson fire. -

September 30, 2020

Valley air about to get worse as wildfire smoke has nowhere to go By Corin Hoggard and Dale Yurong Tuesday, September 29, 2020 FRESNO, Calif. (KFSN) -- Air quality is about to take a turn for the worse as a changing weather pattern will combine with wildfires to fill the Central Valley with smoke again. The last few months have produced a stretch of the worst air quality on record, according to the Air Pollution Control District. Satellite images show smoke gently blowing from several California fires out to the Pacific Ocean, a weather pattern keeping the Valley's air relatively clean for several days now. "Right now we're seeing the smoke aloft," said Maricela Velasquez of the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District. "It's above us. But as the week goes through, we'll continue to see that smoke come onto the Valley floor." Here's how: When you have a fire in the Central Valley -- which is essentially just a bowl -- the smoke can usually get out and air quality won't be bad everywhere. But when a high pressure system comes in, it essentially puts a lid on the bowl and the smoke has nowhere to go so it just collects on the Valley floor. "The blocking high, basically, once it sits over a certain spot it likes to stay there for quite a while," said meteorologist Carlos Molina of the National Weather Service in Hanford. Forecasters at the NWS say the lid will sit on our bowl for at least a week. Air Quality Science Director Jon Klassen of the Valley Air District said, "We're expecting that to continue in the coming days." By that time, our air will have collected smoke from the Creek Fire, the SQF Complex Fire, and even more recent fires to our west, like the Glass Fire in the Bay Area. -

Report on Fires in California

Report On Fires In California Gymnospermous Terencio requires mighty while Quill always hirsling his antispasmodic trumps retrally, he besmirches so diabolically. Is Herschel conventionalized or locular after pandurate Porter catalyses so acidly? Zacharia still revictuals morphologically while complaining Schroeder scry that colonic. All of Calabasas is now under mandatory evacuation due trial the Woolsey fire, department city announced Sunday evening. Unlock an ad free cover now! In this Saturday, Sept. Yucaipa Blvd to Ave E southeast to the intersection of Mesa Grande, east to Wildwood Canyon Rd to trail all portions of Hidden Meadows and the southern portion of the Cherry Valley away from Nancy Lane coming to Beaumont Ave. Angeles National Forest that this been threatened by friendly Fire. As the climate heats up, than other states in their West, including Oregon and Colorado, are seeing larger, more devastating fires and more dangerous air aside from wildfire smoke. Account Status Pending It looks like you started to grease an exhibit but did share complete it. CAL FIRE investigators determined that fire started in two locations. Mouillot F, Field CB. Groups of people walked along the parking lot up the Goebel adult center Friday morning, girl with masks over their noses and others still scrape their pajamas from their first morning escapes. Check high fire ban situation in their area. Another among people refusing to evacuate. Here can, however, ratio are gaps where municipalities lack police authority we act and statewide action is required. Large swaths of Ventura and Los Angeles counties are down under evacuation orders due provide the fires. -

Prioritizing Investments in Our Community's Recovery & Resiliency

Prioritizing Investments in Our Community’s Recovery & Resiliency PG&E Settlement Funds Community Input Survey Data Compilation Responses collected September 15 to October 25, 2020 1 Begins on Page 3 ………………………………………………………. Graph data for Spanish Survey Responses Begins on Page 22 …………………………………..…………………. Graph Data for English Survey Responses Begins on Page 42 ……………….. Open-Ended Response: Shared ideas (Spanish Survey Responses) Begins on Page 44………………….. Open-Ended Response: Shared ideas (English Survey Responses) Begins on Page 189 ..………... Open-Ended Response: Comments for Council (Spanish Responses) Page 190………..……….. Open-Ended Response: Comments for Council (English Survey Responses) 2 SPANISH SURVEY RESPONSES Did you reside within the Santa Rosa city limits during the October 2017 wildfires? Total Responses: 32 yes no 6% 94% 3 SPANISH SURVEY RESPONSES Was your Santa Rosa home or business destroyed or fire damaged in the 2017 wildfires, or did a family member perish in the 2017 wildfires? Total Responses: 32 yes no 25% 75% 4 SPANISH SURVEY RESPONSES Do you currently reside within the Santa Rosa city limits? Total Responses: 32 yes no 13% 87% 5 SPANISH SURVEY RESPONSES Survey Respondents Current Area of Residence 32 Surveys Did not Respond Outside SR within 3% Sonoma County 3% Northwest SR 38% Northeast SR 22% Southwest SR 34% 6 SPANISH SURVEY RESPONSES Where do you reside? Outside City Limits No Response City Limits Out of County Out of State within Sonoma County Provided Northeast Sebastopol 1 - 0 - 0 unknown 1 Fountaingrove 1 -

The Critical Role of Greenbelts in Wildfire Resilience Executive Summary

JUNE 2021 THE CRITICAL ROLE OF GREENBELTS IN WILDFIRE RESILIENCE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Bay Area is at a tipping point in its relationship to wildfire. Decision makers, planners, and advocates must work together on urgent solutions that will keep communities safe from wildfires while also addressing the acute housing crisis. There is huge potential for the Bay Area, and other places across the Western US, to accelerate greenbelts as critical land-use tools to bolster wildfire resilience. Through original research and an assessment of case studies, Greenbelt Alliance has identified four types of greenbelts that play a role in reducing the loss of lives and homes in extreme wildfire events while increasing overall resilience in communities and across landscapes, including: 1 Open space, parks, and preserves 2 Agricultural and working lands such as vineyards, orchards, and farms 3 Greenbelt zones strategically planned and placed inside subdivisions and communities 4 Recreational greenways such as bike paths, playing fields, and golf courses Cover image: Kincade Fire Greenbelt Burn Area at Edge of Windsor, CA by Thomas Rennie. Images this page: (Clockwise from top left) Escaflowne, Bjorn Bakstad, Erin Donalson, f00sion, Bill Oxford GREENBELTS IN WILDFIRE RESILIENCE 3 The role these types of greenbelts play in loss POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS prevention and resilience include: Local, regional, and state policymakers, planners and • Serving as strategic locations for wildfire defense their consultants, and the advocates and nonprofits • Acting as natural wildfire buffers to create separation working on solutions should put this research into from wildlands action and deliver on the following recommendations: • Increasing overall wildfire resilience through land stewardship Recommendation 1 • Conserving biodiversity on fire-adapted lands while Prioritize increasing greenbelts as strategic locations reducing risk for wildfire defense through policy and planning. -

Napa County Community Wildfire Protection Plan

DocuSign Envelope ID: 1B441F17-6F4C-472E-A23F-1934D0CFA167 NAPA COUNTY COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared for Napa Communities Firewise Foundation March 15, 2021 DocuSign Envelope ID: 1B441F17-6F4C-472E-A23F-1934D0CFA167 NAPA COUNTY COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Table of Contents i Preface: What is a Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP)? 1 Executive Summary 2 Section 1: Existing Conditions 5 A. Overview 5 B. Existing Natural and Built Conditions 6 1. Topography 6 2. Vegetation 6 3. Public Ownership 7 4. Fire History 8 5. Key Infrastructure 9 6. Hazard Assessment 10 7. Risk Assessment 19 C. Firefighting Resources 1. Napa County Fire Department 21 2. CAL FIRE 22 Section 2: Collaboration 24 A. Key Partners 24 1. Stakeholders 24 2. Fire Safe Councils (FSCs) 25 Section 3: Proposed Projects and Action Plan 27 A. Proposed Projects 27 1. Origin of Projects 27 2. Priorities 28 B. Proposed Project Categories 28 1. Fuel Management 29 2. Community and Education 29 3. Wildfire Response Support 30 4. Critical Infrastructure Protection 30 5. Planning 30 C. Action Plan 1. Roles and Responsibilities 30 2. Funding Sources 30 Signatures 34 Appendices 35 i DocuSign Envelope ID: 1B441F17-6F4C-472E-A23F-1934D0CFA167 APPENDIX A: NEWLY PROPOSED PROJECTS FORM STAKEHOLDERS APPENDIX B: PROJECTS FROM FIRE SAFE COUNCIL CWPPS APPENDIX C: NAPA COUNTY MULTI-JURISDICTION HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN MITIGATIONS ii DocuSign Envelope ID: 1B441F17-6F4C-472E-A23F-1934D0CFA167 Preface: What is a Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP)? Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPPs) organize a community’s efforts to protect itself from wildfire, and empower citizens to move in a cohesive, common direction. -

![Additional Documents [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1682/additional-documents-pdf-2921682.webp)

Additional Documents [Pdf]

Economic Impacts of Recent Wildfires on Agriculture in California Daniel A. Sumner, University of California, Davis For presentation at a hearing of the California State Assembly hearing of the Committee on Agriculture, Wednesday November 18, 2020 Economic losses from fire are large, varies and complex. But, before turning to agricultural economic losses we must first be clear that the dominate consequences have been the loss of life and serious injury to individuals in both rural and urban areas. In addition, loss of homes and personal treasures represent much more than monetary loss to the people affected. California wildfires have meant personal tragedy for individuals and families throughout the state. Many farm families, including farm owners and operators and farm employees are among those who suffered tragic losses, including deaths and loss of homes. Calculating the economic impacts of those losses is beyond the scope of the data presented below. Here I consider only the reduced capital value of productive farm assets and loss of agriculture income flows caused by wildfires in recent years. This is just a part of a larger whole. It is important to state at the outset that I do not have and have not seen any up-to-date aggregate assessment of agricultural losses from recent wildfires. The most recent round of fires is too new to have complete data, and even for older fires the impacts are so disparate we may never have a full set of economic models and calculations that covers all losses. In that context, it is vital to highlight examples of specific impacts, which provides vital human context to dry calculations. -

Land Use Planning Approaches in the Wildland-Urban Interface an Analysis of Four Western States: California, Colorado, Montana, and Washington

Land Use Planning Approaches in the Wildland-Urban Interface An analysis of four western states: California, Colorado, Montana, and Washington Image credit: Molly Mowery Prepared by: Community Wildfire Planning Center February 2021 TBA Page 1 Acknowledgments The Community Wildfire Planning Center (CWPC) is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization dedicated to helping communities prepare for, adapt to, and recover from wildfires. More information about the CWPC is available at: communitywildfire.org Authors • Molly Mowery, AICP (Executive Director, CWPC) • Darrin Punchard, AICP, CFM (Principal, Punchard Consulting LLC) CWPC Reviewers • Kelly Johnston, RPF, FBAN (Operations Manager, CWPC) • Donald Elliott, FAICP (Director, CWPC) Research Interviewees / Reviewers The authors would like to extend their gratitude to the many individuals who contributed their time through interviews, information-sharing, and/or reviews to make this report as relevant and accurate as possible, including (in alphabetical order): Christopher Barth, Julia Berkey, Daniel Beveridge, Ashley Blazina, Erik de Kok, Edith Hannigan, Karen Hughes, Hilary Lundgren, Rebecca Samulski, John Schelling, Annie Schmidt, and Kristin Sleeper. Their expertise and insights provided valuable perspectives to improve learning opportunities shared in this report. Funding Funding for this research was provided through a generous grant by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Image Credits • Molly Mowery: Cover Page, Overview, California, Colorado, Montana, Washington, Future Directions • U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountains: Executive Summary, Trends and Unknowns • All other image credits as noted in text Contact Information For inquiries related to the Community Wildfire Planning Center or this report, please contact: [email protected] CWPC | Land Use Planning Analysis of the WUI in Four Western States | February 2021 i Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. -

Wildfires Facts + Statistics

Facts + Statistics: Wildfires Catastrophes IN THIS FACTS + STATISTICS Wildland fires Wildfires by year Annual Number of Acres Burned in Wildland Fires, 1980-2020 Top 10 States At High To Extreme Wildfire Risk, 2019 (1) Wildfires By State, 2020 Top 10 States For Wildfires Ranked By Number Of Fires And By Number Of Acres Burned, 2020 Wildfire Losses In The United States, 2010-2019 (1) Top 10 Costliest Wildland Fires In The United States (1) Top 10 Largest California Wildfires (1) Top 10 Most Destructive California Wildfires (1) Top 10 Deadliest California Wildfires (1) SHARE THIS DOWNLOAD TO PDF Wildland fires As many as 90 percent of wildland fires in the United States are caused by people, according to the U.S. Department of Interior. Some human-caused fires result from campfires left unattended, the burning of debris, downed power lines, negligently discarded cigarettes and intentional acts of arson. The remaining 10 percent are started by lightning or lava. According to Verisk’s 2019 Wildfire Risk Analysis 4.5 million U.S. homes were identified at high or extreme risk of wildfire, with more than 2 million in California alone. Wildfires by year 2021: This year’s wildfire season is predicted to be another severe one. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor by August 31, about 90 percent of land in the Western states was experiencing moderate to severe drought. Compounded by June’s heat wave, the threat of wildfires appeared a month ahead of schedule. From January 1 to September 19, 2021 there were 45,118 wildfires, compared with 43,556 in the same period in 2020, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. -

Safeguard Properties Western Wildfire Reference Guide

Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide | 10/26/2020 | Disaster Alert Center Click image for enhanced view Recent events reportedly responsible for structural damage (approximate): California August Complex Fire (1,032,648 acres; 93% containment) August 16 – Present Mendocino, Humboldt, Trinity, Tehama, Lake, Glenn and Colusa Counties 54 structures destroyed; 6 structures damaged Approximate locations at least partially contained in event perimeter: Alder Springs (Glenn County, 95939) Bredehoft Place (Mendocino County, 95428) Chrome (Glenn County, 95963) Covelo (Mendocino County, 95428) Crabtree Place (Trinity County, 95595) Forest Glen (Trinity County, 95552) Hardy Place (Mendocino County, 95428) Houghton Place (Tehama County, 96074) Kettenpom (Trinity County, 95595) Mad River (Trinity County, 95526, 95552) Red Bluff (Tehama County, 96080) Ruth (Trinity County, 95526) Shannon Place (Trinity County, 95595) Zenia (Trinity County, 95595) Media: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/oct/06/california-wildfires-gigafire-first P a g e 1 | 15 Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide | 10/26/2020 | Disaster Alert Center Bobcat Fire (115,796 acres; 92% containment) September 6 – Present Los Angeles County *Northeast of Cogswell Reservoir, San Gabriel Canyon 163 structures destroyed; 47 structures damaged Approximate locations at least partially contained in event perimeter: Big Rock Springs (Los Angeles County, 93544) Hidden Springs (Los Angeles County, 93550) Juniper Hills (Los Angeles County, 93543, 93553)) Littlerock -

Napa Fire Department Annual Report

20 20 N A P A F I R E D E P A R T M E N T A N N U A L R E P O R T D E P A R T M E N T O P E R A T I O N S & I N C I D E N T S & O V E R V I E W P R E V E N T I O N R E S P O N S E Organization & Objectives Programs & Strategies Statistical Analysis TABLE OF CONTENTS Chief's Message........................................................................................1 Vision Statement....................................................................................2 At-a-Glance............................................................................................3 Organizational Chart............................................................................4 Staffing....................................................................................................5 Major Accomplishments........................................................................6 2021 Goals & Initiatives......................................................................6 Department Operations Update..........................................................7 Major Weather & City Wide Incidents..............................................8 Community Engagement & Education..............................................9 Emergency Statistics............................................................................10 Response Overview........................................................................11-12 Prevention Division.......................................................................13-14 In Memoriam........................................................................................15