Goldsmiths College History Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

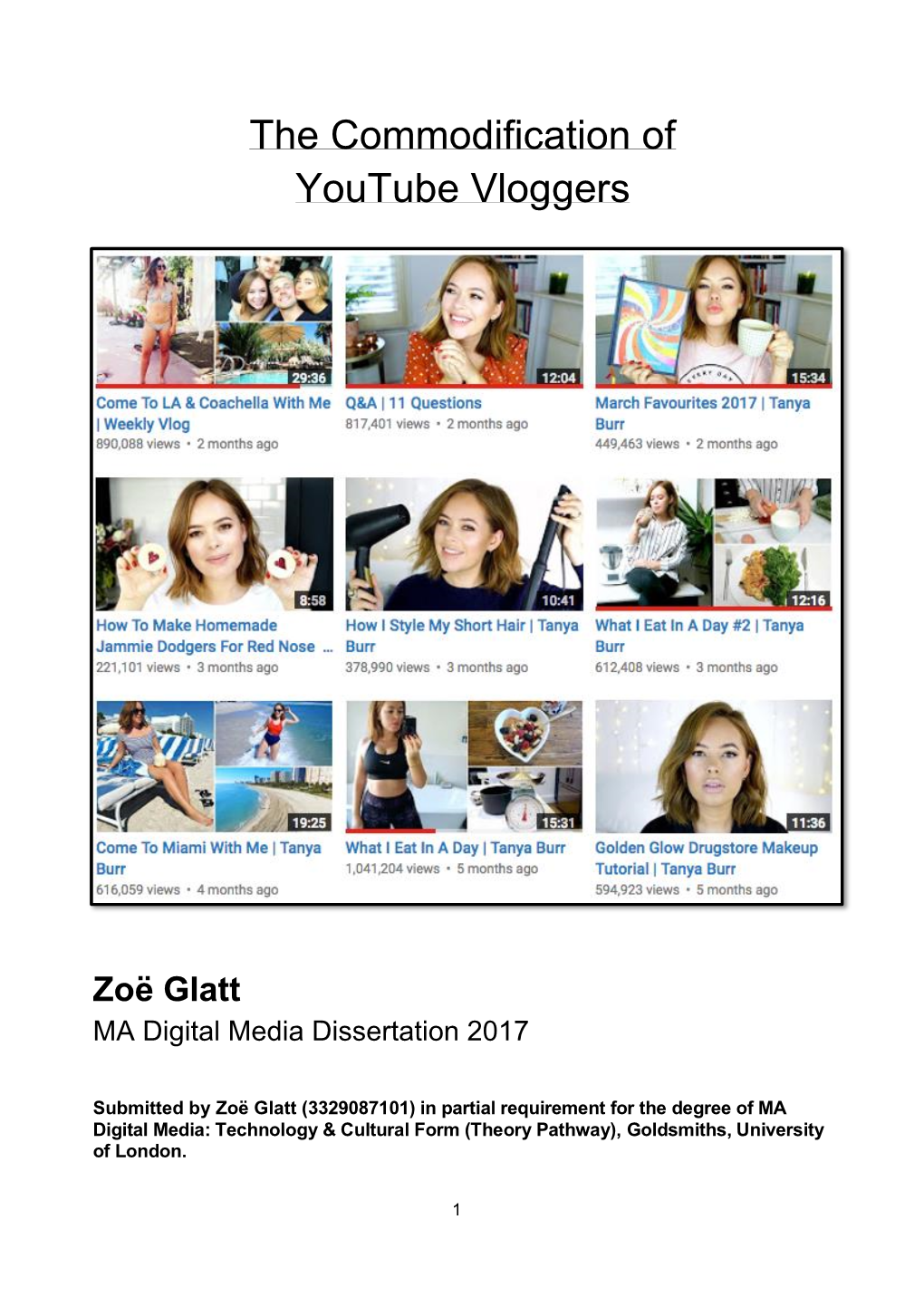

In the Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the Youtuber Zoella

In The Time of the Microcelebrity Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella Jerslev, Anne Published in: International Journal of Communication Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY-ND Citation for published version (APA): Jerslev, A. (2016). In The Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella. International Journal of Communication, 10, 5233-5251. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5078/1822 Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 5233–5251 1932–8036/20160005 In the Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella ANNE JERSLEV University of Copenhagen, Denmark This article discusses the temporal changes in celebrity culture occasioned by the dissemination of digital media, social network sites, and video-sharing platforms, arguing that, in contemporary celebrity culture, different temporalities are connected to the performance of celebrity in different media: a temporality of plenty, of permanent updating related to digital media celebrity; and a temporality of scarcity distinctive of large-scale international film and television celebrities. The article takes issue with the term celebrification and suggests that celebrification on social media platforms works along a temporality of permanent updating, of immediacy and authenticity. Taking UK YouTube vlogger and microcelebrity Zoella as the analytical case, the article points out that microcelebrity strategies are especially connected with the display of accessibility, presence, and intimacy online; moreover, the broadening of processes of celebrification beyond YouTube may put pressure on microcelebrities’ claim to authenticity. Keywords: celebrification, microcelebrity, YouTubers, vlogging, social media, celebrity culture YouTubers are a huge phenomenon online. -

Make a Mini Dance

OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Parent Guide Read the “Directions” sheets for step-by-step instructions. SUMMARY In this activity children will watch two very short videos online, then create their own mini dances. WHY This activity will get children thinking about the ways their bodies move. They will think about how movements can represent shapes, such as letters in a word. TIME ■ 10–20 minutes RECOMMENDED AGE GROUP This activity will work best for children in kindergarten through 4th grade. GET READY ■ Read Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring together. Ballet for Martha tells the story of three artists who worked together to make a treasured work of American art. For tips on reading this book together, check out the Guided Reading Activity (http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/pdf/dance/dance_reading.pdf). ■ Read the Step Back in Time sheets. YOU NEED ■ Directions sheets (attached) ■ Ballet for Martha book (optional) ■ Step Back in Time sheets (attached) ■ ThinkAbout sheet (attached) ■ Open space to move ■ Video camera (optional) ■ Computer with Internet and speakers/headphones More information at http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/activities/dance/. OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Directions, page 1 of 2 For adults and kids to follow together. 1. On May 11, 2011, the Internet search company Google celebrated Martha Graham’s birthday with a special “Google Doodle,” which spelled out G-o-o-g-l-e using a dancer’s movements. Take a look at the video (http://www.google.com/logos/2011/ graham.html). -

The Pointless Book: Started by Alfie Deyes, Finished by You Free

FREE THE POINTLESS BOOK: STARTED BY ALFIE DEYES, FINISHED BY YOU PDF Alfie Deyes | 192 pages | 04 Sep 2014 | Bonnier Books Ltd | 9781905825905 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom The Pointless Book (The Pointless Book, #1) by Alfie Deyes Rainy afternoon? Not sure when your friends are going to arrive? Another twenty minutes before Finished by You bus comes? The Pointless Book will have something silly to keep you chuckling until then. Alfie Dayes is the inimitable Finished by You sensation who has channelled his cheery, upbeat personality into creating this book full of hilarious activities, pranks and games. The perfect book to keep you distracted and amused, no matter the situation. The Pointless Book is exactly what it says Finished by You is: a book brimming with random, pointless ideas. What The Pointless Book: Started by Alfie Deyes need to know though is just how much it will make you laugh as you make your way through its pages. Unfortunately, this seems to be a complete page-by-page copy of Wreck This Journal with a 'youtubers' name stuck on the front page. The 'activities' are unoriginal and it seems like a severe lack Lot's of things Finished by You do, my goal is to complete this fully by the end of the year. It's a really fun, clever book. I'd recommend this book to anyone. Just bought this book and it's amazing. Lots of hidden things within this book! Really fun and creative! Please sign in to write a review. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will update your details. -

2045 the Year Man Becomes Immortal by LEV GROSSMAN Thursday, Feb

2045 The Year Man Becomes Immortal By LEV GROSSMAN Thursday, Feb. 10, 2011 Photo--Illustration by Phillip Toledano for TIME On Feb. 15, 1965, a diffident but self-possessed high school student named Raymond Kurzweil appeared as a guest on a game show called I've Got a Secret. He was introduced by the host, Steve Allen, then he played a short musical composition on a piano. The idea was that Kurzweil was hiding an unusual fact and the panelists — they included a comedian and a former Miss America — had to guess what it was. On the show (see the clip on YouTube), the beauty queen did a good job of grilling Kurzweil, but the comedian got the win: the music was composed by a computer. Kurzweil got $200. (See TIME's photo-essay "Cyberdyne's Real Robot.") Kurzweil then demonstrated the computer, which he built himself — a desk-size affair with loudly clacking relays, hooked up to a typewriter. The panelists were pretty blasé about it; they were more impressed by Kurzweil's age than by anything he'd actually done. They were ready to move on to Mrs. Chester Loney of Rough and Ready, Calif., whose secret was that she'd been President Lyndon Johnson's first-grade teacher. But Kurzweil would spend much of the rest of his career working out what his demonstration meant. Creating a work of art is one of those activities we reserve for humans and humans only. It's an act of self-expression; you're not supposed to be able to do it if you don't have a self. -

Universidade Federal Do Rio De Janeiro Centro De Filosofia E Ciências Humanas Escola De Comunicação

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO MEU ÍNTIMO, UM MERCADO: CURADORIA DE VIDA EM ZOELLA Júlia Ceciliano Nasra Rio de Janeiro/RJ 2018 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO MEU ÍNTIMO, UM MERCADO: CURADORIA DE VIDA EM ZOELLA Júlia Ceciliano Nasra Monografia de graduação apresentada à Escola de Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Bacharel em Comunicação Social, Habilitação em Produção Editorial. Orientadora: Prof. Dr.ª Amaury Fernandes da Silva Júnior Rio de Janeiro/ RJ 2018 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) N264 Nasra, Júlia Ceciliano Meu íntimo, um mercado: curadoria de vida em Zoella / Júlia Ceciliano Nasra. – 2018. 71 f.: il. Orientador: Prof. Dr Amaury Fernandes da Silva Júnior Monografia (graduação) – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Escola de Comunicação, Habilitação Produção Editorial, Rio de Janeiro, 2018. 1. Redes sociais. 2. YouTube. 3. Celebridade. 4. Intimidade. I. Silva Júnior, Amaury Fernandes da. II. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Escola de Comunicação. CDD: 302.3 Elaborada por: Érica dos Santos Resende CRB-7/5105 AGRADECIMENTO Aos meus pais, Bianca, Marcelo, Maurício e Luciane, por incentivarem e proporcionarem minha educação. Essa conquista também é de vocês. Ao meu irmão Pedro, a quem sempre quero dar o exemplo da dedicação e comprometimento. Ao meu irmão de quatro patas, Guga, pela companhia durante as tardes de escrita. Ao meu Guigo, por me aguentar falar sobre a monografia incessantemente e por ter um abraço que sempre me acalma. -

In What Way Is the Rhetoric Used in Youtube Videos Altering the Perception of the LGBTQ+ Community for Both Its Members and Non-Members?

In What Way Is the Rhetoric Used in YouTube Videos Altering the Perception of the LGBTQ+ Community for Both Its Members and Non-Members? NATALIE MAURER Produced in Thomas Wright’s Spring 2018 ENC 1102 Introduction The LBGTQ community has become a much more prevalent part of today's society. Over the past several years, the LGBTQ community has been recognized more equally in comparison to other groups in society. June 2015 was a huge turning point for the community due to the legalization of same sex marriage. The legalization of same sex marriage in June 2015 had a great impact on the LBGTQ community, as well as non-members. With an increase in new media platforms like YouTube, content on the LGBTQ community has become more accessible and more prevalent than decades ago. LGBTQ media has been represented in movies, television shows, short videos, and even books. The exposure of LQBTQ characters in a popular 2000s sitcom called Will & Grace paved the way for LGBTQ representation in media. A study conducted by Edward Schiappa and others concluded that exposure to LGBTQ communities through TV helped educate Americans, therefore reducing sexual prejudice. Unfortunately, the way the LBGTQ community is portrayed through online media such as YouTube has an effect on LGBTQ members and non-members, and it has yet to be studied. Most “young people's experiences are affected by the present context characterized by the rapidly increasing prevalence of new (online) media” because of their exposure to several media outlets (McInroy and Craig 32). This gap has led to the research question does the LGBTQ representation on YouTube negatively or positively represent this community to its members, and in what way is the community impacted by this representation as well as non- members? One positive way the LGBTQ community was represented through media was on the popular TV show Will & Grace. -

A Walled Garden Turned Into a Rain Forest

A Walled Garden Turned Into a Rain Forest Pelle Snickars More than ten months after the iPhone was introduced, Lev Grossman in Time Magazine, reflected upon the most valuable invention of 2007. At first he could not make up his mind. Admittedly, he argued, there had been a lot written about the iPhone —and if truth be told, a massive amount of articles, extensive media coverage, hype, “and a lot of guff too.” Grossman hesitated: he confessed that he could not type on the iPhone; it was too slow, too expensive, and even too big. “It doesn’t support my work e- mail. It’s locked to AT&T. Steve Jobs secretly hates puppies. And—all together now— we’re sick of hearing about it!” Yet, when Grossman had finished with his litany of complains, the iPhone was nevertheless in his opinion, “the best thing invented this year.” He gave five reasons why this was the case. First of all, the iPhone had made design important for smartphones. At a time when most tech companies did not treat form seriously at all, Apple had made style a trademark of their seminal product. Of course, Apple had always knew that good design was as important as good technology, and the iPhone was therefore no exception. Still, it was something of a stylistic epitome, and to Grossman even “pretty”. Another of his reasons had to do with touch. Apple didn’t invent the touchscreen, but according to Grossman the company engineers had finally understood what to do with it. In short, Apple’s engineers used the touchscreen to sort of innovate past the GUI, which Apple once pioneered with the Mac, to create “a whole new kind of interface, a tactile one that gives users the illusion of actually physically manipulating data with their hands.” Other reasons, in Grossman view, why the iPhone was the most valuable invention of 2007, was its benefit to the mobile market in general. -

GCSE MEDIA STUDIES Close Study Products

1 GCSE MEDIA STUDIES Close Study Products For candidates entering for the 2020 examination To be issued to candidates at the start of their course of study. Information • These Close Study Products (CSPs) have been selected as a starting point for the analysis of media products as part of the GCSE Media Studies course. • Some questions in the GCSE Media Studies Examination Papers will focus on these CSPs. • You must study all of these products. • You are advised to supplement this list with other products. • You cannot take this booklet into the examinations. 2 Close Study Products Introduction What are Close Study Products? Close Study Products (CSPs) are a range of media products that you must study in order to meet the requirements of the specification and prepare for the exams. A ‘product’ means something produced by a media industry for a media audience, for example, a television programme, a website or a video game. How are the CSPs chosen? The CSPs are chosen by the exam board. Between them, they enable you to study examples of all the following media forms: • Television • Film • Radio • Newspapers • Magazines • Advertising and marketing • Online, social and participatory media • Video games • Music video. Some of these forms must be studied in depth: including at least one audio/visual form, one print form and one online, social and participatory media form. What does ‘in depth study’ mean? The forms you will study in depth are: • Television (audio/visual) • Newspapers (Print) • Online, social and participatory media • Video games. For this specification you will study some linked online, social and participatory media products in conjunction with associated video games. -

HOW to MAKE MONEY with Youtube Earn Cash, Market Yourself, Reach Your Customers, and Grow Your Business on the World’S Most Popular Video-Sharing Site

HOW TO MAKE MONEY WITH YouTube Earn Cash, Market Yourself, Reach Your Customers, and Grow Your Business on the World’s Most Popular Video-Sharing Site BRAD AND DEBRA SCHEPP New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2009 by Brad and Debra Schepp. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the pub- lisher. ISBN: 978-0-07-162618-7 MHID: 0-07-162618-2 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-162136-6, MHID: 0-07-162136-9. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trade- mark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative please visit the Contact Us page at www.mhprofessional.com. How to Make Money with YouTube is no way authorized by, endorsed, or affiliated with YouTube or its sub- sidiaries. All references to YouTube and other trademarkedproperties are used in accordance with the Fair Use Doctrine and are not meant to imply that this book is a YouTube product for advertising or other com- mercial purposes. -

How Harry Potter Became the Boy Who Lived Forever

12/17/12 How Harry Potter Became the Boy Who Lived Forever ‑‑ Printout ‑‑ TIME Back to Article Click to Print Thursday, Jul. 07, 2011 The Boy Who Lived Forever By Lev Grossman J.K. Rowling probably isn't going to write any more Harry Potter books. That doesn't mean there won't be any more. It just means they won't be written by J.K. Rowling. Instead they'll be written by people like Racheline Maltese. Maltese is 38. She's an actor and a professional writer — journalism, cultural criticism, fiction, poetry. She describes herself as queer. She lives in New York City. She's a fan of Harry Potter. Sometimes she writes stories about Harry and the other characters from the Potterverse and posts them online for free. "For me, it's sort of like an acting or improvisation exercise," Maltese says. "You have known characters. You apply a set of given circumstances to them. Then you wait and see what happens." (See a Harry Potter primer.) Maltese is a writer of fan fiction: stories and novels that make use of the characters and settings from other people's professional creative work. Fan fiction is what literature might look like if it were reinvented from scratch after a nuclear apocalypse by a band of brilliant pop-culture junkies trapped in a sealed bunker. They don't do it for money. That's not what it's about. The writers write it and put it up online just for the satisfaction. They're fans, but they're not silent, couchbound consumers of media. -

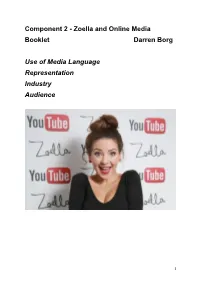

Zoella and Online Media Booklet Darren Borg Use

Component 2 - Zoella and Online Media Booklet Darren Borg Use of Media Language Representation Industry Audience 1 Full name: Zoe Elizabeth Sugg Age: 28 She was working as an apprentice at an interior design company when she created her first blog, "Zoella", in February 2009 The fashion, beauty and lifestyle blog expanded into a YouTube channel in 2009, while she was working for British clothing retailer New Look She was named as one of the National Citizen Service’s ambassadors in 2013, helping to promote the newly launched youth service. The following year she was named as the first "Digital Ambassador" for Mind, the mental health charity Her main channel, Zoella, is mostly fashion, beauty hauls, and "favourites" videos (showing her favourite products of the previous month). Her second channel, MoreZoella, contains mostly vlogs where she shows her viewers what she does in her day. YouTube subscribers – in excess of 11 million Partner is Alfie Deyes, creator of PointlessBlog She is the named author of three novels, aimed at a young audience and detailing the life of a fictitious female blogger, although she works with an editorial team and a ‘ghost-writer’ through her publisher, Penguin Books She launched a range of beauty products under the brand name Zoella Beauty in September 2014 2 ACTIVITY Watch the first ten minutes of the ‘Rise of the Superstar Vloggers’ documentary (BBC 4) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h_rn1h_tCaQ) What has vlogging revolutionised? The way we connect with each other What is there a tendency to do? Share everything -

Is Parkland's SONALI the Next Big Thing in Pop?

THE MUSIC Is Parkland’s SONALI the next big thing in pop? ISSUE EXPERIENCE THIS SUMMER DAN MARINO, OFFICIAL BRAND AMBASSADOR DON’T MISS A SPECIAL MEET & GREET AT ENCORE RESORT WITH NFL HALL OF FAMER DAN MARINO ON AUGUST 18TH CALL 407.410.4388 FOR MORE DETAILS! Imagine vacationing in a luxurious 4 to 13-bedroom home just 5 minutes from Disney for less than the cost of a hotel room.Each home features a private pool, gourmet kitchen, living and dining rooms and so much more. Just steps away from your door, you will enjoy the thrills of our Encore Clubhouse and AquaPark dedicated to resort-style euphoria with restaurants, bar, fitness center, concierge, shuttle services to the parks, an incredible kids splash area, water slides, pool, cabanas, bar & grille and arcade. Why settle for ordinary when you can stay in extraordinary at Encore Resort at Reunion. BOOK 3 NIGHTS GET THE 4TH NIGHT FREE WHEN YOU BOOK BETWEEN JULY 1ST AND DECEMBER 20TH. MENTION BOOKING CODE: LSBUY34C* EncoreReunion.com | 877.795.6085 | 7635 Fairfax Drive, Reunion, FL 34747 *Offer subject to availability and to change without notice. Offer may not be combined with any other offers or discounts. Offer may not be used on previously booked stays. Blackout dates are July 4, 2018, November 18, 2018 through November 25, 2018, and December 16, 2018 through January 5, 2019. Reservations are not guaranteed, and homes are based on availability. ENCORE AD-LM-7.18.indd 1 6/5/2018 11:51:34 AM OUR NAME WILL BRING YOU IN, EXPERIENCE BUT OUR FOOD WILL BRING YOU BACK! THIS SUMMER DAN MARINO, OFFICIAL BRAND AMBASSADOR Mike Ponluang, Owner & Executive Chef DON’T MISS A SPECIAL MEET & GREET AT ENCORE RESORT TH WITH NFL HALL OF FAMER DAN MARINO ON AUGUST 18 Savor chef/owner Mike Ponluang’s delectable Thai and Asian fusion cuisine, along with his CALL 407.410.4388 FOR MORE DETAILS! sublime selection of sushi, sashimi, and specialty rolls, for lunch and dinner.