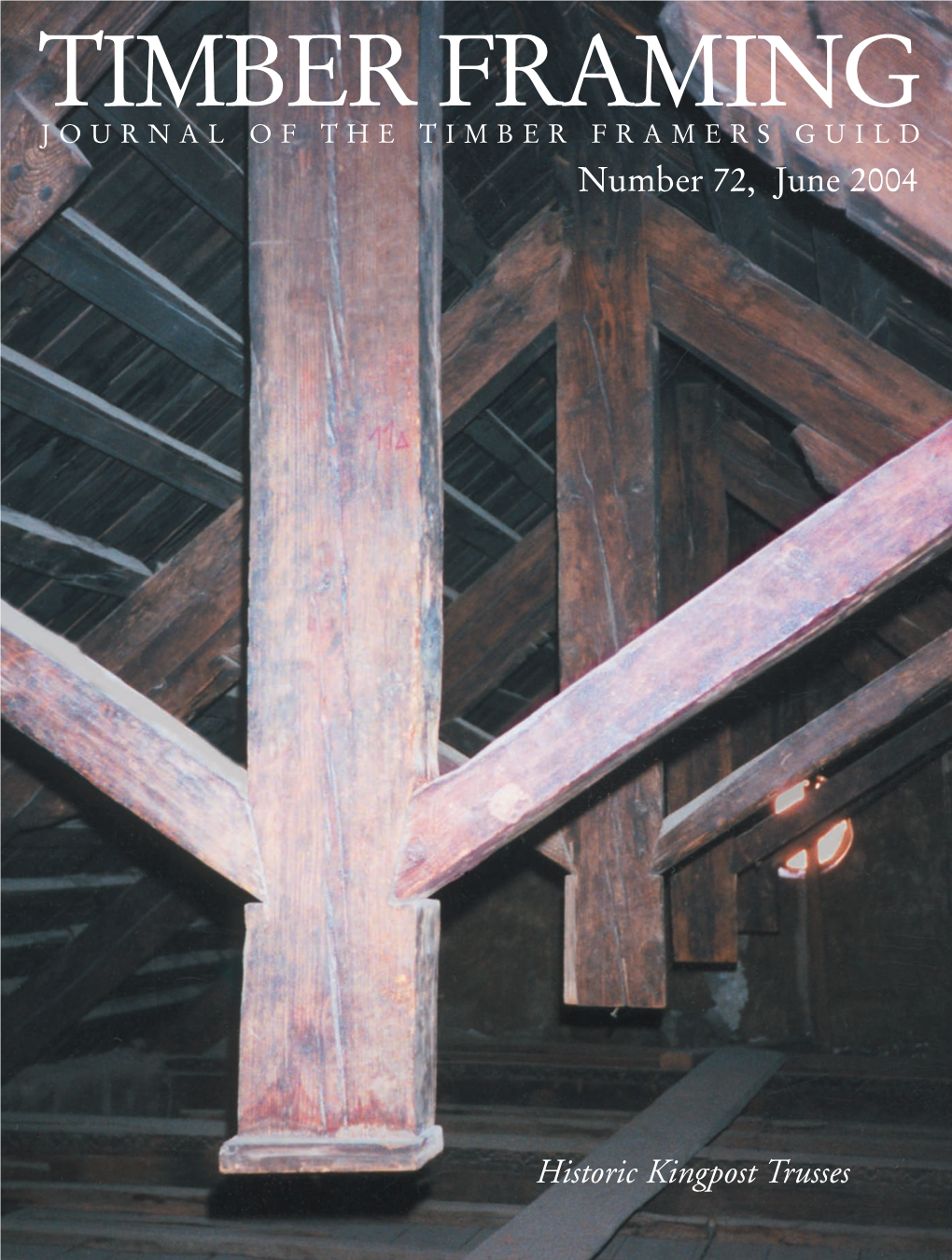

TIMBER FRAMING JOURNAL of the TIMBER FRAMERS GUILD Number 72, June 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 061053 - Miscellaneous Rough Carpentry

SECTION 061053 - MISCELLANEOUS ROUGH CARPENTRY PART 1 - GENERAL 1.1 RELATED DOCUMENTS A. Drawings and general provisions of the Contract, including General and Supplementary Conditions and Division 01 Specification Sections, apply to this Section. 1.2 SUMMARY A. This Section includes the following: 1. Wood framing, blocking, and nailers 2. Wood battens, shims, and furring (for wall panel attachment). 3. Plywood sheathing for miscellaneous structures and replacement of deteriorated roof sheathing. B. Related Sections include the following: 1. Section 075216 "SBS Modified Bituminous Membrane Roofing" for adhesively applied 2-ply, SBS bituminous membrane roofing, with self-adhered base ply sheet. 2. Section 076200 "Sheet Metal Flashing and Trim" for installing sheet metal flashing and trim integral with roofing. 1.3 DEFINITIONS A. Dimension Lumber: Lumber of 2-inches nominal or greater but less than 5-inches nominal in least dimension. B. Lumber grading agencies, and the abbreviations used to reference them, include the following: 1. NLGA: National Lumber Grades Authority. 2. WCLIB: West Coast Lumber Inspection Bureau. 3. WWPA: Western Wood Products Association. 1.4 QUALITY ASSURANCE A. Testing Agency Qualifications: For testing agency providing classification marking for fire- retardant treated material, an inspection agency acceptable to authorities having jurisdiction that periodically performs inspections to verify that the material bearing the classification marking is representative of the material tested. PRSD – Thompson Elementary School Roof Replacement 061053 – MISCELLANEOUS ROUGH CARPENTRY July, 2012 Page 1 of 7 B. Forest Certification: For the following wood products, provide materials produced from wood obtained from forests certified by an FSC-accredited certification body to comply with FSC 1.2, "Principles and Criteria": 1. -

Step 4. Roof-Bearing Assemblies

Step 4. Roof-Bearing Assemblies ilclcngCI First, to have previously selected, from a wide variety of options, the combination of roof-bearing assembly (RBA) and tie-down system that is "right" for you and for your design. Second, to get the segments of your RBA safely up onto the wall (unless you have chosen to create the RBA in place, on top of the wall) and to make strong connections where they meet. Third, to "tie" this assembly to the foundation in such a way that the maximum expected wind velocity (a.k.a. the design wind load) cannot turn the RBA/roof into an ILFO (identified low-flying object). Walk-Through Jt extend continuously around the structure. Every wall carrying any roof load will need an • During the process of finalizing your RBA, but modern roof designs for square and design and creating plans, you will have rectangular buildings very seldom bear on selected the type of RBA to be used. Among more than two of the four walls (assuming a the factors that can influence this decision square or rectangular building). Even so, one are: might still choose to have the RBA be a —whether the RBA will act as a lintel over continuous collar, in order to tie the whole openings; [This would allow you to use less building together. A rigid, continuous RBA wood in creating the nonbearing door and could also serve as the lintel over all door and window frames, but may bring you to use window openings in the building, thus more wood in the RBA itself. -

LP Solidstart LVL Technical Guide

U.S. Technical Guide L P S o l i d S t a r t LV L Technical Guide 2900Fb-2.0E Please verify availability with the LP SolidStart Engineered Wood Products distributor in your area prior to specifying these products. Introduction Designed to Outperform Traditional Lumber LP® SolidStart® Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) is a vast SOFTWARE FOR EASY, RELIABLE DESIGN improvement over traditional lumber. Problems that naturally occur as Our design/specification software enhances your in-house sawn lumber dries — twisting, splitting, checking, crowning and warping — design capabilities. It ofers accurate designs for a wide variety of are greatly reduced. applications with interfaces for printed output or plotted drawings. Through our distributors, we ofer component design review services THE STRENGTH IS IN THE ENGINEERING for designs using LP SolidStart Engineered Wood Products. LP SolidStart LVL is made from ultrasonically and visually graded veneers arranged in a specific pattern to maximize the strength and CODE EVALUATION stifness of the veneers and to disperse the naturally occurring LP SolidStart Laminated Veneer Lumber has been evaluated for characteristics of wood, such as knots, that can weaken a sawn lumber compliance with major US building codes. For the most current code beam. The veneers are then bonded with waterproof adhesives under reports, contact your LP SolidStart Engineered Wood Products pressure and heat. LP SolidStart LVL beams are exceptionally strong, distributor, visit LPCorp.com or for: solid and straight, making them excellent for most primary load- • ICC-ES evaluation report ESR-2403 visit www.icc-es.org carrying beam applications. • APA product report PR-L280 visit www.apawood.org LP SolidStart LVL 2900F -2.0E: AVAILABLE SIZES b FRIEND TO THE ENVIRONMENT LP SolidStart LVL 2900F -2.0E is available in a range of depths and b LP SolidStart LVL is a building material with built-in lengths, and is available in standard thicknesses of 1-3/4" and 3-1/2". -

Carpentry/Carpenter

Job Ready Credential Blueprint 46.0201- Carpentry/Carpenter Carpentry Code: 4215 / Version: 01 Copyright © 2017. All Rights Reserved. Carpentry General Assessment Information Blueprint Contents General Assessment Information Sample Written Items Written Assessment Information Performance Assessment Information Specic Competencies Covered in the Test Sample Performance Job Test Type: The Carpentry industry-based credential is included in NOCTI’s Job Ready assessment battery. Job Ready assessments measure technical skills at the occupational level and include items which gauge factual and theoretical knowledge. Job Ready assessments typically oer both a written and performance component and can be used at the secondary and post-secondary levels. Job Ready assessments can be delivered in an online or paper/pencil format. Revision Team: The assessment content is based on input from secondary, post-secondary, and business/industry representatives from the states of Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Pennsylvania, and Texas. CIP Code 46.0201- Carpentry/Carpenter Career Cluster 2- Architecture and Construction 47-2031.01 – Construction Carpenters The Association for Career and Technical Education (ACTE), the leading professional organization for career and technical educators, commends all students who participate in career and technical education programs and choose to validate their educational attainment through rigorous technical assessments. In taking this assessment you demonstrate to your school, your parents and guardians, your -

18Th Annual Eastern Conference of the Timber Framers Guild

Timber Framers Guild 18th Annual Eastern Conference November 14–17, 2002, Burlington, Vermont The Timber Framer’s Panel Company www.foardpanel.com P.O. Box 185, West Chesterfield, NH 03466 ● 603-256-8800 ● [email protected] Contents FRANK BAKER Healthy Businesses. 3 BRUCE BEEKEN Furniture from the Forest . 4 BEN BRUNGRABER AND GRIGG MULLEN Engineering Day to Day ENGINEERING TRACK . 6 BEN BRUNGRABER AND DICK SCHMIDT Codes: the Practical and the Possible ENGINEERING TRACK . 8 RUDY CHRISTIAN Understanding and Using Square Rule Layout WORKSHOP . 13 RICHARD CORMIER Chip Carving PRE-CONFERENCE WORKSHOP . 14 DAVID FISCHETTI AND ED LEVIN Historical Forms ENGINEERING TRACK . 15 ANDERS FROSTRUP Is Big Best or Beautiful? . 19 ANDERS FROSTRUP Stave Churches . 21 SIMON GNEHM The Swiss Carpenter Apprenticeship . 22 JOE HOWARD Radio Frequency Vacuum Drying of Large Timber: an Overview . 24 JOSH JACKSON Plumb Line and Bubble Scribing DEMONSTRATION . 26 LES JOZSA Wood Morphology Related to Log Quality. 28 MICHELLE KANTOR Construction Law and Contract Management: Know your Risks. 30 WITOLD KARWOWSKI Annihilated Heritage . 31 STEVE LAWRENCE, GORDON MACDONALD, AND JAIME WARD Penguins in Bondage DEMO 33 ED LEVIN AND DICK SCHMIDT Pity the Poor Rafter Pair ENGINEERING TRACK . 35 MATTHYS LEVY Why Buildings Don’t Fall Down FEATURED SPEAKER . 37 JAN LEWANDOSKI Vernacular Wooden Roof Trusses: Form and Repair . 38 GORDON MACDONALD Building a Ballista for the BBC . 39 CURTIS MILTON ET AL Math Wizards OPEN ASSISTANCE . 40 HARRELSON STANLEY Efficient Tool Sharpening for Professionals DEMONSTRATION . 42 THOMAS VISSER Historic Barns: Preserving a Threatened Heritage FEATURED SPEAKER . 44 Cover illustration of the Norwell Crane by Barbara Cahill. -

UFGS 06 10 00 Rough Carpentry

************************************************************************** USACE / NAVFAC / AFCEC / NASA UFGS-06 10 00 (August 2016) Change 2 - 11/18 ------------------------------------ Preparing Activity: NAVFAC Superseding UFGS-06 10 00 (February 2012) UNIFIED FACILITIES GUIDE SPECIFICATIONS References are in agreement with UMRL dated July 2021 ************************************************************************** SECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS DIVISION 06 - WOOD, PLASTICS, AND COMPOSITES SECTION 06 10 00 ROUGH CARPENTRY 08/16, CHG 2: 11/18 PART 1 GENERAL 1.1 REFERENCES 1.2 SUBMITTALS 1.3 DELIVERY AND STORAGE 1.4 GRADING AND MARKING 1.4.1 Lumber 1.4.2 Structural Glued Laminated Timber 1.4.3 Plywood 1.4.4 Structural-Use and OSB Panels 1.4.5 Preservative-Treated Lumber and Plywood 1.4.6 Fire-Retardant Treated Lumber 1.4.7 Hardboard, Gypsum Board, and Fiberboard 1.4.8 Plastic Lumber 1.5 SIZES AND SURFACING 1.6 MOISTURE CONTENT 1.7 PRESERVATIVE TREATMENT 1.7.1 Existing Structures 1.7.2 New Construction 1.8 FIRE-RETARDANT TREATMENT 1.9 QUALITY ASSURANCE 1.9.1 Drawing Requirements 1.9.2 Data Required 1.9.3 Humidity Requirements 1.9.4 Plastic Lumber Performance 1.10 ENVIRONMENTAL REQUIREMENTS 1.11 CERTIFICATIONS 1.11.1 Certified Wood Grades 1.11.2 Certified Sustainably Harvested Wood 1.11.3 Indoor Air Quality Certifications 1.11.3.1 Adhesives and Sealants 1.11.3.2 Composite Wood, Wood Structural Panel and Agrifiber Products SECTION 06 10 00 Page 1 PART 2 PRODUCTS 2.1 MATERIALS 2.1.1 Virgin Lumber 2.1.2 Salvaged Lumber 2.1.3 Recovered Lumber -

D12 – Collar Beam Roof

D12 – Collar Beam Roof FRILO Software GmbH www.frilo.com [email protected] As of 21/04/2016 D12 D12 – Collar Beam Roof Note: This document describes the Eurocode-specific application. Documents containing old standards are available in our documentation archive at www.frilo.de >> Dokumentation >>Manuals>Archive. Contents Application options 4 Basis of calculation 5 Definition of the structural system 6 Definition via coordinates 6 Projection-related definition 8 Spanwise definition 9 Supports/purlins 10 Collar beam support 11 Cross section 12 Loads 13 Output 14 Output profile 14 Options - settings 16 Further information and descriptions are available in the relevant documentations: FDC – Basic Operating Instructions General instructions for the manipulation of the user interface FDC – Menu items General description of the typical menu items of Frilo software applications FDC – Output and printing Output and printing FDC - Import and export Interfaces to other applications (ASCII, RTF, DXF …) FCC Frilo.Control.Center - the easy-to-use administration module for projects and items FDD Frilo.Document.Designer - document management based on PDF Frilo.System.Next Installation, configuration, network, database FRILO Software GmbH Page 3 Collar Beam Roof Application options The D12 application allows the calculation of conventional collar beam roofs with sway/non-sway collar beams as well as rafter roofs. Available standards . EN 1995-1-1:2004/2008/2014 . DIN EN 1995-1-1:2010/2013 . ÖNORM EN 1995-1-1:2009/2010/2015 . BS EN 1995-1-1:2012 . UNI EN 1995-1/NTC still optionally available: . DIN 1052:2004/2008 In addition to typical roof loads such as uniformly distributed, weight, snow and wind loads, additional loads can be defined as uniform linear loads, concentrated or trapezoidal loads and assigned to groups of action. -

La Taxe D'aménagement

YONNE La Taxe d’Aménagement - TA - CompignyCompigny VinneufVinneuf Courlon-Courlon-Courlon- VilleneuveVilleneuve Plessis-Plessis- PerceneigePerceneige VilleneuveVilleneuve sur-sur-sur- sur-sur-sur- Saint-Saint- la-Guyardla-Guyardla-Guyard Saint-Saint- YonneYonne SerginesSergines YonneYonne JeanJeanJean PaillyPailly Saint-Maurice-aux-Saint-Maurice-aux- VilleblevinVilleblevin SerbonnesSerbonnes Riches-HommesRiches-Hommes ChampignyChampigny MicheryMichery ChaumontChaumont LaLa Thorigny-sur-OreuseThorigny-sur-Oreuse Saint-AgnanSaint-Agnan Saint-AgnanSaint-Agnan VillemanocheVillemanoche Chapelle-Chapelle- Gisy-les-Gisy-les- Chapelle-Chapelle- CourgenayCourgenay Pont-sur-Pont-sur- sur-sur- LaLa PostollePostolle Pont-sur-Pont-sur- NoblesNobles sur-sur-sur- LaLa PostollePostolle YonneYonne OreuseOreuse VillethierryVillethierry EEvvvrrryyy VillethierryVillethierry LaillyLailly BagneauxBagneaux VilleperrotVilleperrot CuyCuy VoisinesVoisines Saint-Saint- SoucySoucy LixyLixy VillenavotteVillenavotte Villeneuve-Villeneuve- SérotinSérotin Villeneuve-Villeneuve- Saint-Denis-lès-SensSaint-Denis-lès-Sens ValleryVallery Foissy-Foissy- l'Archevêquel'Archevêquel'Archevêque ValleryVallery Courtois-sur-Courtois-sur- Fontaine-la-Fontaine-la- LesLesLes Foissy-Foissy- BrannayBrannay Saint-ClémentSaint-Clément Gaillarde sur-sur-sur- NaillyNailly YonneYonne Saint-ClémentSaint-Clément GaillardeGaillarde ClérimoisClérimois sur-sur- MolinonsMolinons SalignySaligny DollotDollot Saint-Martin-Saint-Martin- VanneVanne FlacyFlacy VillebougisVillebougis Saint-Martin-Saint-Martin- -

Designing for Durability CONTINUING EDUCATION Strategies for Achieving Maximum Durability with Wood-Frame Construction Sponsored by Rethink Wood

EDUCATIONAL-ADVERTISEMENT Designing for Durability EDUCATION CONTINUING Strategies for achieving maximum durability with wood-frame construction Sponsored by reThink Wood rchitects specify wood for many Examples of wood buildings that have (glulam), cross laminated timber (CLT), and reasons, including cost, ease and stood for centuries exist all over the world, nail-laminated timber, along with a variety A efficiency of construction, design including the Horyu-ji temple in Ikaruga, of structural composite lumber products, are versatility, and sustainability—as well as Japan, built in the eighth century, stave enabling increased dimensional stability and its beauty and the innate appeal of nature churches in Norway, including one in Urnes strength, and greater long-span capabilities. and natural materials. Innovative new built in 1150, and many more. Today, wood These innovations are leading to taller, technologies and building systems are also is being used in a wider range of buildings highly innovative wood buildings. Examples leading to the increased use of wood as a than would have been possible even 20 years include (among others) a 10-story CLT structural material, not only in houses, ago. Next-generation lumber and mass timber apartment building in Australia, a 14-story schools, and other traditional applications, products, such as glue-laminated timber timber-frame apartment in Norway, but in larger, taller, and more visionary wood buildings. But even as the use of wood is expanding, one significant characteristic of wood buildings is often underestimated: their durability. Misperceptions still exist that buildings made of materials such as concrete or steel last longer than buildings made of wood. -

06 10 00 --- Rough Carpentry

DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION GUIDELINES AND STANDARDS DIVISION 6 WOODS & PLASTICS 06 10 00 • ROUGH CARPENTRY SECTION INCLUDES Dimensional Wood Framing Sheathing Prefabricated Trusses Wood Blocking Engineered Wood Framing Termite Shield RELATED SECTIONS 03 30 00 Concrete 06 20 00 Finish Carpentry 06 50 00 Structural Plastics & Composites 06 65 00 Plastic and Composite Trim 07 62 00 Sheet Metal Trim & Flashing ABBREVIATIONS-TESTING, CERTIFYING AND GRADING AGENCIES AITC- American Institute of Timber Construction www.aitc-glulam.org ALSC- American Lumber Standards Committee www.alsc.org ANSI- American National Standards Institute www.ansi.org APA- The Engineered Wood Association, (formerly American Plywood Association) www.apawood.org AWPA- American Wood Protection Association www.awpa.com CSA- Canadian Standards Association www.csa.ca FSC- Forest Stewardship Council www.fscus.org NIST- National Institute for Standards and Technology www.nist.gov SFI-Sustainable Forest Initiative www.sfiprogram.org TPI- Truss Plate Institute www.tpint.org LOAD CALCULATIONS DESIGN Calculate loads and specify the fiber stress for lumber. Avoid over-designing that will result in unnecessarily high material costs. Spruce, Pine or Fir should be adequate for most conditions; provide a rationale for any other species. ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES PRODUCTS Use of wood from well-managed forests is preferred. Specify one or more of the following standards: Forest Stewardship Council (FSC); Sustainable Forest Initiative (SFI); or Canadian Standards Association (CSA). Using certified wood encourages a well-managed forest industry. Look for engineered wood products with certified wood content, recycled or recovered wood, and/or products that are produced within 500 miles of the project site. The use of engineered wood should be evaluated on R 06 10 00 ROUGH CARPENTRY………. -

Platform Frame Construction (Part 2)

STRUCTURAL TIMBER 4 ENGINEERING BULLETIN Timber frame structures – platform frame construction (part 2) Introduction Horizontal diaphragms and bracing In Timber Engineering Bulletin No. 3 (part 1 in this sub-series on platform Horizontal diaphragms in platform frame buildings are provided by the frame construction), the composition and terminology used for platform intermediate floors (with a wood-based subdeck material fixed directly to the timber frame building structures, and the structural engineering checks which joists) and the roof structure (with either a wood-based ‘sarking’ board or are required to verify the adequacy of the vertical load paths and the strength discrete diagonal bracing members) (Figure 3). These horizontal structural and stiff ness of the individual framing members, was introduced. diaphragms transfer horizontal loads acting on the building to the foundations by means of their connections to the wall panels (or vertical diaphragms). This Timber Engineering Bulletin introduces the engineering checks for overall building stability and the stability checks required for the wall diaphragms which provide shear (or racking) resistance to a platform timber frame structure. Robustness and disproportionate collapse design considerations for platform timber frame buildings are addressed in part 3 of this sub-series. Overall stability To achieve its stability, platform timber frame construction relies on the diaphragm action of floor structures to transfer horizontal forces to a distributed arrangement of loadbearing walls. The load bearing walls provide both vertical support and horizontal racking and shear resistance. Due to the presence of open-plan or asymmetric layouts or the occurrence of large openings in loadbearing walls, it may be necessary to provide other means of providing stability to the building, for example by the use of ‘portalised’ or ‘rigid’ frames or discrete braced bays as indicated in Figure 1. -

Creating a Timber Frame House

Creating a Timber Frame House A Step by Step Guide by Brice Cochran Copyright © 2014 Timber Frame HQ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. ISBN # 978-0-692-20875-5 DISCLAIMER: This book details the author’s personal experiences with and opinions about timber framing and home building. The author is not licensed as an engineer or architect. Although the author and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time, the author and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. Except as specifically stated in this book, neither the author or publisher, nor any authors, contributors, or other representatives will be liable for damages arising out of or in connection with the use of this book. This is a comprehensive limitation of liability that applies to all damages of any kind, including (without limitation) compensatory; direct, indirect or consequential damages; income or profit; loss of or damage to property and claims of third parties. You understand that this book is not intended as a substitute for consultation with a licensed engineering professional. Before you begin any project in any way, you will need to consult a professional to ensure that you are doing what’s best for your situation.