Inadequate Protection of Tenants' Property During Eviction and the Need for Reform Larry Weiser Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

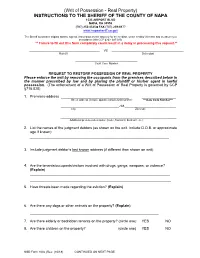

Writ of Possession

(Writ of Possession - Real Property) INSTRUCTIONS TO THE SHERIFF OF THE COUNTY OF NAPA 1535 AIRPORT BLVD NAPA, CA 94558 (707) 253-4325 FAX (707) 259-8177 www.napasheriff.ca.gov The Sheriff must have original written, signed, instructions by the attorney for the creditor, or the creditor if he/she has no attorney in accordance with CCP §262; 687.010. ** Failure to fill out this form completely could result in a delay in processing this request.** ___________________________________________ VS ____________________________________________ Plaintiff Defendant ______________________________________ Court Case Number REQUEST TO RESTORE POSSESSION OF REAL PROPERTY Please enforce the writ by removing the occupants from the premises described below in the manner prescribed by law and by placing the plaintiff or his/her agent in lawful possession. (The enforcement of a Writ of Possession of Real Property is governed by CCP §715.020) 1. Premises-address __________________________________ _________________ Street address (include apartment/suite/unit number) ***Gate Code Number*** ________________________________________, CA ___________________________________ City Zip Code __________________________________________________________ Additional premises description (Color, front unit, back unit etc.) 2. List the names of the judgment debtors (as shown on the writ. Include D.O.B. or approximate age if known): ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

California Statewide Rent and Eviction Law 1 Any Reproduction Or Use of This Document, Its Content, Or Its Format Is Prohibited

11/1/19 Edition, by Arthur Meirson California Statewide & David R. Gellman (frequentlyFA askedQs questions) Rent and Eviction Law This article is provided as a resource for understanding the changes which are taking place in San Francisco’s real estate community, and summarizes those changes as they are understood on the publication date. Updated versions of this article may appear on the firm’s website at www.g3mh.com. Tenant Protection Act of 2019. On September 11, 2019, the California Legislature enacted a sweeping statewide law creating rent and eviction controls affecting most residential real properties in California. Governor Gavin Newsom signed the law on October 8, 2019, and it will go into effect on January 1, 2020, with some provisions being retroactive to March 15, 2019. As a result of this law, almost all residential real properties in California will now be subject to a degree of rent control, and will be subject to “just cause” eviction rules, meaning landlords will no longer be able to evict a tenant simply because a fixed term lease has expired. The law will not apply to new housing built within the past 15 years, and a limited number of other types of properties are exempt. The law does not supersede more stringent rent and eviction controls that exist in certain cities and counties, like San Francisco; however, it does affect residential properties in those jurisdictions that were previously exempt from local rent and eviction control laws. What are “Rent “Rent Control” ordinances are laws which limit the amount by which rents may be increased. -

Does a New Federal Law Protect You from Eviction?

Does a New Federal Law Protect You from Eviction? Congress recently passed the CARES Act, a new law that may protect you from eviction until after July 25, 2020. The law protects tenants from eviction for not paying rent (or other fees or charges) between March 27 and July 25 if they live in a property listed below. If you live in one of these properties, your landlord cannot start an eviction against you during this period. Your landlord also cannot charge you late fees or interest during this period. Starting on July 26, your landlord can give you a 30-day eviction notice if you did not pay your rent between March 27 and July 25. You will still have to pay the full rent you owe for March 27 to July 25. If you have any loss of income, you may be able to reduce the amount you owe in monthly rent. The person or organization to contact is listed next to each program. You may be able to find out if you live in one of the protected properties by searching the property by name or address at https://nlihc.org/federal-moratoriums. Take this document to your landlord if you think this law applies to you and you are having trouble paying your rent. You are protected by this law if you live in: • public housing, section 8 housing where rental housing loan program, or in the subsidy comes with the unit that housing rehabilitated under the housing you are renting, or private housing with preservation grant program (Section 533) a HUD voucher (contact your public (contact your landlord or management housing authority); agent); • a property that is -

The Covid-19 Eviction Crisis: an Estimated 30-40 Million People in America Are at Risk

THE COVID-19 EVICTION CRISIS: AN ESTIMATED 30-40 MILLION PEOPLE IN AMERICA ARE AT RISK Emily Benfer, Wake Forest University School of Law David Bloom Robinson, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Stacy Butler, Innovation for Justice Program, University of Arizona College of Law Lavar Edmonds, The Eviction Lab at Princeton University Sam Gilman, The COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project Katherine Lucas McKay, The Aspen Institute Zach Neumann, The Aspen Institute / The COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project Lisa Owens, City Life/Vida Urbana Neil Steinkamp, Stout Diane Yentel, National Low Income Housing Coalition AUGUST 7, 2020 THE COVID-19 EVICTION CRISIS: AN ESTIMATED 30-40 MILLION PEOPLE IN AMERICA ARE AT RISK Introduction The United States may be facing the most severe housing crisis in its history. According to the latest analysis of weekly U.S. Census data, as federal, state and local protections and resources expire and in the absence of robust and swift intervention, an estimated 30–40 million people in America could be at risk of eviction in the next several months. Many property owners, who lack the credit or financial ability to cover rental payment arrears, will struggle to pay their mortgages and property taxes, and maintain properties. The COVID-19 housing crisis has sharply increased the risk of foreclosure and bankruptcy, especially among small property owners; long-term harm to renter families and individuals; disruption of the affordable housing market; and destabilization of communities across the United States. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers, academics and advocates have conducted continuous analysis of the effect of the public health crisis and economic depression on renters and the housing market. -

DCCA Opinion No. 01-CV-1437: Sylvia Maalouf V. Imran Butt, Et

Notice: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the Atlantic and Maryland Reporters. Users are requested to notify the Clerk of the Court of any formal errors so that corrections may be made before the bound volumes go to press. DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA COURT OF APPEALS No. 01-CV-1437 SYLVIA MAALOUF, APPELLANT, V. IMRAN BUTT, et al., APPELLEES. Appeal from the Superior Court of the District of Columbia (SC-20704-00) (Hon. Milton C. Lee, Hearing Commissioner) (Hon. Steffen W. Graae, Trial Judge) (Submitted November 19, 2002 Decided February 20, 2003) Sylvia Maalouf, pro se. Sean D. Hummel was on the brief, for appellees. Before TERRY and STEADMAN, Associate Judges, and FERREN, Senior Judge. FERREN, Senior Judge: In this small claims case, appellant Maalouf, proceeding pro se, sought damages from appellee Butt for the loss of her car at Butt’s repair shop. The hearing commissioner, sustained by a trial judge, found for Maalouf but awarded her only $150 for the loss of the car radio. Maalouf contends on appeal that the commissioner erred in denying full damages for loss of the car on the ground that Maalouf had failed to present sufficient evidence of the car’s value (in addition to the value of the radio) as of the time she brought the vehicle to Butt’s shop for repair. We reverse and remand for further 2 proceedings. Maalouf testified that her car, while under Butt’s control, had been vandalized twice and eventually stolen. The hearing commissioner accepted her testimony as true for purposes of decision, and the issue thus became the amount of recovery.1 “The traditional standard for calculating damages for conversion is the fair market value of the property at the time of the conversion”– here, as of the time Maalouf brought the car to Butt’s shop for repair. -

Four Property Wrongs of Self Storage

FOUR PROPERTY WRONGS OF SELF-STORAGE LAW Jeffrey Douglas Jones Table of Contents Introduction: Setting Aside the Constitutional Question I. The Wild, Wild Lease: Self-Storage Agreements and Default Practices A. Owner’s Liens B. Lien Attachment and Risk of Loss C. From Default to Lien Enforcement D. Lien Enforcement Transferring Title to Landlord E. Lien Enforcement by Public Auction II. The Property Wrongs of Self-Storage Law A. The “Crap” Rule B. Tort Law Misfires and the Elimination of Bailments C. Ignored Parallels to Residential Landlord-Tenant Reform D. Treasure Trove and Self-Storage Treasure Hunters III. Conclusion: Legal Reform, Voluntariness, and the Property Ethic “Own Less” Jeffrey Douglas Jones, Associate Professor of Law, Lewis & Clark Law School; J.D., The University of Michigan Law School-Ann Arbor; Ph.D. Philosophy, The University of Wisconsin-Madison. [Thanks] 1 Jones / Four Property Wrongs of Self-Storage Law Introduction: Setting Aside the Constitutional Question Self-storage leases are troubling. Under such leases, self-storage facility owners may freely dispose of defaulting tenants’ medical and tax records, family ashes, heirlooms, etc. in the same manner as they would treat fungible items such as chairs or a bookshelf. Facility owners are legally entitled to do so through facility-sponsored auctions, most of which are unrestricted by any duty to conduct commercially reasonable sales. Still worse, these legal self- storage practices have generated a clandestine culture of treasure-hunting that often leaves tenants—some of whom default due to medical emergencies, bankruptcy or who are homeless working poor—with little opportunity either to regain good standing or obtain fair market value for their belongings. -

There Are Four Steps in the Eviction Process: 1. the Notice to Vacate 2. Filing the Suit 3. Going to Court 4. Writ of Possession

Taylor County Constable Pct. 1 2021 There are four steps in the Eviction process: 1. The notice to vacate 2. Filing the Suit 3. Going to Court 4. Writ of Possession 1. The notice to vacate If a landlord alleges a tenant that is behind on rent or has a lease violation, the Landlord is required by law to give the tenant a three day written notice to vacate the premises. How to deliver the notice options… A) In person – Personally delivered to the tenant or any person residing at the premises who is 16 years of age or older B) Personally delivered – to the premises by attaching the notice to the INSIDE of the main entry door. C) By mail – By regular mail, Registered mail or certified mail, return receipt requested, to the premises in question D) If Above Options Won’t Work – Securely affix the notice to the outside of the main entry door in an envelope with the tenant’s name, address and the word “IMPORTANT DOCUMENT” or similar language AND by 5pm of the same day deposit in the mail a copy of the notice to the tenant. **The Texas Property Code 24.005 requires you the Landlord to deliver the written notice, and then wait three days before filing your suit in Justice Court. This is a legal requirement which must be met and cannot be overlooked. If a landlord is requesting attorney’s fee, the landlord must give a 10 day Notice to vacate. 2. Filing the Suit You must file an original petition with the Court and pay $121.00 (subject to change). -

Eviction: Get the Facts

Consumer’s Edge Consumer Protection Division, Maryland Office of the Attorney General Brian E. Frosh, Maryland Attorney General Eviction: Get the Facts “My landlord says he’s going to evict me tomorrow if Reasons for Eviction I don’t pay the rent...Can he do that? What can I do? A landlord cannot evict you simply because you have filed Where will I go?” a complaint or a lawsuit against them or have joined a tenant’s association. This is called a “retaliatory eviction,” The prospect of being forced out of your home and having and you may be able to stop an eviction by showing the your belongings put on the street is frightening. However, court that your landlord is evicting you for one of these it’s important to understand what an eviction is (and is reasons. not) and what a landlord can and can’t do. A landlord can evict you for: • Non-payment of rent. Your landlord can begin the eviction process as soon as your rent due date has passed and you have not paid the rent. In most in- stances, you can stop the eviction any time before the sheriff actually comes to evict you by paying the landlord the rent that is owed. • Witholding rent. Never try to force a landlord to make repairs to your home by withholding the rent. The landlord can evict you for non-payment of rent. Instead, go to your District Court and ask to file a rent escrow complaint. A judge may allow you to pay your rent into an escrow account Eviction is a legal process. -

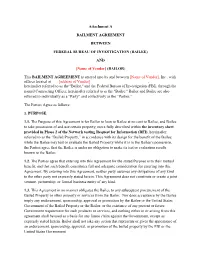

(BAILOR) This BAILMENT

Attachment A BAILMENT AGREEMENT BETWEEN FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION (BAILEE) AND [Name of Vendor] (BAILOR) This BAILMENT AGREEMENT is entered into by and between [Name of Vendor], Inc., with offices located at [address of Vendor] , hereinafter referred to as the "Bailor," and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), through the named Contracting Officer, hereinafter referred to as the "Bailee." Bailor and Bailee are also referred to individually as a “Party” and collectively as the “Parties.” The Parties Agree as follows: 1. PURPOSE. 1.1. The Purpose of this Agreement is for Bailor to loan to Bailee at no cost to Bailee, and Bailee to take possession of and use certain property, more fully described within the inventory sheet provided in Phase 2 of the Network testing Request for Information (RFI), hereinafter referred to as the “Bailed Property,” in accordance with its design for the benefit of the Bailee; while the Bailee may test or evaluate the Bailed Property while it is in the Bailee’s possession, the Parties agree that the Bailee is under no obligation to make its test or evaluation results known to the Bailor. 1.2. The Parties agree that entering into this Agreement for the stated Purpose is to their mutual benefit, and that such benefit constitutes full and adequate consideration for entering into this Agreement. By entering into this Agreement, neither party assumes any obligations of any kind to the other party not expressly stated herein. This Agreement does not constitute or create a joint venture, partnership, or formal business entity of any kind. 1.3. -

New Jersey Department of Community Affairs Division of Codes and Standards Landlord-Tenant Information Service

New Jersey Department of Community Affairs Division of Codes and Standards Landlord-Tenant Information Service GROUNDS FOR AN EVICTION BULLETIN Updated February 2008 An eviction is an actual expulsion of a tenant out of the premises. A landlord must have good cause to evict a tenant. There are several grounds for a good cause eviction. Each cause, except for nonpayment of rent, must be described in detail by the landlord in a written notice to the tenant. A “Notice to Quit” is required for all good cause evictions, except for an eviction for nonpayment of rent. A “Notice to Quit” is a notice given by the landlord ending the tenancy and telling the tenant to leave the premises. However, a Judgment for Possession must be entered by the Court before the tenant is required to move. A “Notice to Cease” may also be required in some cases. A “Notice to Cease” serves as a warning notice; this notice tells the tenant to stop the wrongfully conduct. If the tenant does not comply with the “Notice to Cease,” a “Notice to Quit” may be served on the tenant. After giving a Notice to Quit, the landlord may file suit for an eviction. If a suit for eviction is filed and the landlord wins his case, he may be granted a Judgment for Possession. A Judgment for Possession ends the tenancy and allows the landlord to have the tenant evicted from the rental premises. No residential landlord may evict or fail to renew a lease, whether it is a written or an oral lease without good cause. -

![[1] the Basics of Property Division](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2246/1-the-basics-of-property-division-1212246.webp)

[1] the Basics of Property Division

RESTATEMENT OF THE LAW FOURTH, PROPERTY PROJECTED OVERALL TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME [1] THE BASICS OF PROPERTY DIVISION ONE: DEFINITIONS Chapter 1. Meanings of “Property” Chapter 2. Property as a Relation Chapter 3. Separation into Things Chapter 4. Things versus Legal Things Chapter 5. Tangible and Intangible Things Chapter 6. Contracts as Property [pointers to Contracts Restatement and UCC] Chapter 7. Property in Information [pointer to Intellectual Property Restatement(s)] Chapter 8. Entitlement and Interest Chapter 9. In Rem Rights Chapter 10. Residual Claims Chapter 11. Customary Rights Chapter 12. Quasi-Property DIVISION TWO: ACCESSION Chapter 13. Scope of Legal Thing Chapter 14. Ad Coelum Chapter 15. Airspace Chapter 16. Minerals Chapter 17. Caves Chapter 18. Accretion, etc. [cross-reference to water law, Vol. 2, Ch. 2] Chapter 19. Fruits, etc. Chapter 20. Fixtures Chapter 21. Increase Chapter 22. Confusion Chapter 23. Improvements DIVISION THREE: POSSESSION Chapter 24. De Facto Possession Chapter 25. Customary Legal Possession Chapter 26. Basic Legal Possession Chapter 27. Rights to Possess Chapter 28. Ownership versus Possession Chapter 29. Transitivity of Rights to Possess Chapter 30. Sequential Possession, Finders Chapter 31. Adverse Possession Chapter 32. Adverse Possession and Prescription Chapter 33. Interests Not Subject to Adverse Possession Chapter 34. State of Mind in Adverse Possession xvii © 2016 by The American Law Institute Preliminary draft - not approved Chapter 35. Tacking in Adverse Possession DIVISION FOUR: ACQUISITION Chapter 36. Acquisition by Possession Chapter 37. Acquisition by Accession Chapter 38. Specification Chapter 39. Creation VOLUME [2] INTERFERENCES WITH, AND LIMITS ON, OWNERSHIP AND POSSESSION Introductory Note (including requirements of possession) DIVISION ONE: PROPERTY TORTS Chapter 1. -

Property and Conveyancing William Schwartz

Annual Survey of Massachusetts Law Volume 1960 Article 4 1-1-1960 Chapter 1: Property and Conveyancing William Schwartz Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/asml Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, William (1960) "Chapter 1: Property and Conveyancing ," Annual Survey of Massachusetts aL w: Vol. 1960, Article 4. Schwartz: Chapter 1: Property and Conveyancing PAR T I Private Law CHAPTER 1 Property and Conveyancing WILLIAM SCHWARTZ §I.I. Landlord and tenant: Termination of tenancy at will by con veyance. In Stedfast v. Rebon Realty Co.} the Supreme Judicial Court held that an existing tenancy at will was terminated by a con veyance of the leased premises to a corporation dominated by the land lord, and that the receipt of rent after the conveyance to the corpora tion resulted in the creation of a new tenancy at will between the tenant and the corporation. This new tenancy (which may be created even though the tenant has no notice of the conveyance to the corpora tion) is governed by a different tort standard than the old tenancy; the obligation of the corporate landlord is to use reasonable care to main tain the common passageways within its control in as good a condition as they were, or appeared to be, at the time of the creation of the new tenancy. Although the landlord's conveyance of his realty to a corpo ration dominated by the landlord may be motivated by business and estate planning considerations and may not have been viewed primaril~ as an attempt to reduce the landlord's tort obligations, we still cannot lose sight of the adverse and detrimental effect that the Stedfast rule has on injured tenants.