Property and Conveyancing William Schwartz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

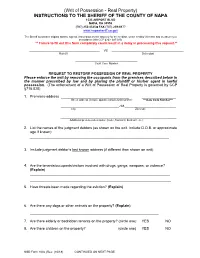

Writ of Possession

(Writ of Possession - Real Property) INSTRUCTIONS TO THE SHERIFF OF THE COUNTY OF NAPA 1535 AIRPORT BLVD NAPA, CA 94558 (707) 253-4325 FAX (707) 259-8177 www.napasheriff.ca.gov The Sheriff must have original written, signed, instructions by the attorney for the creditor, or the creditor if he/she has no attorney in accordance with CCP §262; 687.010. ** Failure to fill out this form completely could result in a delay in processing this request.** ___________________________________________ VS ____________________________________________ Plaintiff Defendant ______________________________________ Court Case Number REQUEST TO RESTORE POSSESSION OF REAL PROPERTY Please enforce the writ by removing the occupants from the premises described below in the manner prescribed by law and by placing the plaintiff or his/her agent in lawful possession. (The enforcement of a Writ of Possession of Real Property is governed by CCP §715.020) 1. Premises-address __________________________________ _________________ Street address (include apartment/suite/unit number) ***Gate Code Number*** ________________________________________, CA ___________________________________ City Zip Code __________________________________________________________ Additional premises description (Color, front unit, back unit etc.) 2. List the names of the judgment debtors (as shown on the writ. Include D.O.B. or approximate age if known): ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

California Statewide Rent and Eviction Law 1 Any Reproduction Or Use of This Document, Its Content, Or Its Format Is Prohibited

11/1/19 Edition, by Arthur Meirson California Statewide & David R. Gellman (frequentlyFA askedQs questions) Rent and Eviction Law This article is provided as a resource for understanding the changes which are taking place in San Francisco’s real estate community, and summarizes those changes as they are understood on the publication date. Updated versions of this article may appear on the firm’s website at www.g3mh.com. Tenant Protection Act of 2019. On September 11, 2019, the California Legislature enacted a sweeping statewide law creating rent and eviction controls affecting most residential real properties in California. Governor Gavin Newsom signed the law on October 8, 2019, and it will go into effect on January 1, 2020, with some provisions being retroactive to March 15, 2019. As a result of this law, almost all residential real properties in California will now be subject to a degree of rent control, and will be subject to “just cause” eviction rules, meaning landlords will no longer be able to evict a tenant simply because a fixed term lease has expired. The law will not apply to new housing built within the past 15 years, and a limited number of other types of properties are exempt. The law does not supersede more stringent rent and eviction controls that exist in certain cities and counties, like San Francisco; however, it does affect residential properties in those jurisdictions that were previously exempt from local rent and eviction control laws. What are “Rent “Rent Control” ordinances are laws which limit the amount by which rents may be increased. -

Does a New Federal Law Protect You from Eviction?

Does a New Federal Law Protect You from Eviction? Congress recently passed the CARES Act, a new law that may protect you from eviction until after July 25, 2020. The law protects tenants from eviction for not paying rent (or other fees or charges) between March 27 and July 25 if they live in a property listed below. If you live in one of these properties, your landlord cannot start an eviction against you during this period. Your landlord also cannot charge you late fees or interest during this period. Starting on July 26, your landlord can give you a 30-day eviction notice if you did not pay your rent between March 27 and July 25. You will still have to pay the full rent you owe for March 27 to July 25. If you have any loss of income, you may be able to reduce the amount you owe in monthly rent. The person or organization to contact is listed next to each program. You may be able to find out if you live in one of the protected properties by searching the property by name or address at https://nlihc.org/federal-moratoriums. Take this document to your landlord if you think this law applies to you and you are having trouble paying your rent. You are protected by this law if you live in: • public housing, section 8 housing where rental housing loan program, or in the subsidy comes with the unit that housing rehabilitated under the housing you are renting, or private housing with preservation grant program (Section 533) a HUD voucher (contact your public (contact your landlord or management housing authority); agent); • a property that is -

The Covid-19 Eviction Crisis: an Estimated 30-40 Million People in America Are at Risk

THE COVID-19 EVICTION CRISIS: AN ESTIMATED 30-40 MILLION PEOPLE IN AMERICA ARE AT RISK Emily Benfer, Wake Forest University School of Law David Bloom Robinson, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Stacy Butler, Innovation for Justice Program, University of Arizona College of Law Lavar Edmonds, The Eviction Lab at Princeton University Sam Gilman, The COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project Katherine Lucas McKay, The Aspen Institute Zach Neumann, The Aspen Institute / The COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project Lisa Owens, City Life/Vida Urbana Neil Steinkamp, Stout Diane Yentel, National Low Income Housing Coalition AUGUST 7, 2020 THE COVID-19 EVICTION CRISIS: AN ESTIMATED 30-40 MILLION PEOPLE IN AMERICA ARE AT RISK Introduction The United States may be facing the most severe housing crisis in its history. According to the latest analysis of weekly U.S. Census data, as federal, state and local protections and resources expire and in the absence of robust and swift intervention, an estimated 30–40 million people in America could be at risk of eviction in the next several months. Many property owners, who lack the credit or financial ability to cover rental payment arrears, will struggle to pay their mortgages and property taxes, and maintain properties. The COVID-19 housing crisis has sharply increased the risk of foreclosure and bankruptcy, especially among small property owners; long-term harm to renter families and individuals; disruption of the affordable housing market; and destabilization of communities across the United States. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers, academics and advocates have conducted continuous analysis of the effect of the public health crisis and economic depression on renters and the housing market. -

Inadequate Protection of Tenants' Property During Eviction and the Need for Reform Larry Weiser Prof

Loyola Consumer Law Review Volume 20 | Issue 3 Article 2 2008 Adding Injury to Injury: Inadequate Protection of Tenants' Property During Eviction and the Need for Reform Larry Weiser Prof. & Dir. Of Clinical Law Programs, Gonzaga University, School of Law Matthew .T Treu Assoc., Alverson, Taylor, Mortensen & Sanders, Law Vegas Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lclr Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons Recommended Citation Larry Weiser & Matthew T. Treu Adding Injury to Injury: Inadequate Protection of Tenants' Property During Eviction and the Need for Reform, 20 Loy. Consumer L. Rev. 247 (2008). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lclr/vol20/iss3/2 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola Consumer Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEA TURE AR TICLES Adding Injury to Injury: Inadequate Protection of Tenants' Property During Eviction and the Need for Reform By Larry Weiser* & Matthew W. Treu** I. Introduction Irene Parker, an 82 year-old single woman with health problems, was evicted at Christmas-time due to repair and rental disputes with her landlords. The amount in dispute was $1,200, far less than the monetary value of Ms. Parker's life possessions, which was $15,000. Upon being evicted and having everything she owned put on a public curb, Ms. Parker was forced to pay for a cab so that she could stay at a friend's home until she could find a new place to live. -

There Are Four Steps in the Eviction Process: 1. the Notice to Vacate 2. Filing the Suit 3. Going to Court 4. Writ of Possession

Taylor County Constable Pct. 1 2021 There are four steps in the Eviction process: 1. The notice to vacate 2. Filing the Suit 3. Going to Court 4. Writ of Possession 1. The notice to vacate If a landlord alleges a tenant that is behind on rent or has a lease violation, the Landlord is required by law to give the tenant a three day written notice to vacate the premises. How to deliver the notice options… A) In person – Personally delivered to the tenant or any person residing at the premises who is 16 years of age or older B) Personally delivered – to the premises by attaching the notice to the INSIDE of the main entry door. C) By mail – By regular mail, Registered mail or certified mail, return receipt requested, to the premises in question D) If Above Options Won’t Work – Securely affix the notice to the outside of the main entry door in an envelope with the tenant’s name, address and the word “IMPORTANT DOCUMENT” or similar language AND by 5pm of the same day deposit in the mail a copy of the notice to the tenant. **The Texas Property Code 24.005 requires you the Landlord to deliver the written notice, and then wait three days before filing your suit in Justice Court. This is a legal requirement which must be met and cannot be overlooked. If a landlord is requesting attorney’s fee, the landlord must give a 10 day Notice to vacate. 2. Filing the Suit You must file an original petition with the Court and pay $121.00 (subject to change). -

Eviction: Get the Facts

Consumer’s Edge Consumer Protection Division, Maryland Office of the Attorney General Brian E. Frosh, Maryland Attorney General Eviction: Get the Facts “My landlord says he’s going to evict me tomorrow if Reasons for Eviction I don’t pay the rent...Can he do that? What can I do? A landlord cannot evict you simply because you have filed Where will I go?” a complaint or a lawsuit against them or have joined a tenant’s association. This is called a “retaliatory eviction,” The prospect of being forced out of your home and having and you may be able to stop an eviction by showing the your belongings put on the street is frightening. However, court that your landlord is evicting you for one of these it’s important to understand what an eviction is (and is reasons. not) and what a landlord can and can’t do. A landlord can evict you for: • Non-payment of rent. Your landlord can begin the eviction process as soon as your rent due date has passed and you have not paid the rent. In most in- stances, you can stop the eviction any time before the sheriff actually comes to evict you by paying the landlord the rent that is owed. • Witholding rent. Never try to force a landlord to make repairs to your home by withholding the rent. The landlord can evict you for non-payment of rent. Instead, go to your District Court and ask to file a rent escrow complaint. A judge may allow you to pay your rent into an escrow account Eviction is a legal process. -

New Jersey Department of Community Affairs Division of Codes and Standards Landlord-Tenant Information Service

New Jersey Department of Community Affairs Division of Codes and Standards Landlord-Tenant Information Service GROUNDS FOR AN EVICTION BULLETIN Updated February 2008 An eviction is an actual expulsion of a tenant out of the premises. A landlord must have good cause to evict a tenant. There are several grounds for a good cause eviction. Each cause, except for nonpayment of rent, must be described in detail by the landlord in a written notice to the tenant. A “Notice to Quit” is required for all good cause evictions, except for an eviction for nonpayment of rent. A “Notice to Quit” is a notice given by the landlord ending the tenancy and telling the tenant to leave the premises. However, a Judgment for Possession must be entered by the Court before the tenant is required to move. A “Notice to Cease” may also be required in some cases. A “Notice to Cease” serves as a warning notice; this notice tells the tenant to stop the wrongfully conduct. If the tenant does not comply with the “Notice to Cease,” a “Notice to Quit” may be served on the tenant. After giving a Notice to Quit, the landlord may file suit for an eviction. If a suit for eviction is filed and the landlord wins his case, he may be granted a Judgment for Possession. A Judgment for Possession ends the tenancy and allows the landlord to have the tenant evicted from the rental premises. No residential landlord may evict or fail to renew a lease, whether it is a written or an oral lease without good cause. -

QUESTION 1 Purchaser Acquired Blackacre from Seller in 1988

QUESTION 1 Purchaser acquired Blackacre from Seller in 1988. Seller had purchased the property in 1978. Throughout Seller's ownership, Blackacre had been described by a metes and bounds legal description, which Seller believed to include an island within a stream. Seller conveyed title to Blackacre to Purchaser through a special warranty deed describing Blackacre with the same legal description through which Seller acquired it. At all times while Seller owned Blackacre, she thought she owned the island. In 1978, she built a foot bridge to the island to allow her to drive a tractor mower on it. During the summer, she regularly mowed the grass and maintained a picnic table on the island. Upon acquiring Blackacre, Purchaser continued to mow the grass and maintain the picnic table during the summer. In 1994, Neighbor, who owns the property adjacent to Blackacre, had a survey done of his property (the accuracy of which is not disputed) which shows that he owns the island. In 1998, Neighbor demanded that Purchaser remove the picnic table and stop trespassing on the island. QUESTION: Discuss any claims which Purchaser might assert to establish his right to the island or which he may have against Seller. DISCUSSION FOR QUESTION 1 I. Mr. Plaintiffs Claims versus Mr. Neighbor One who maintains continuous, exclusive, open, and adverse possession of real property for the requisite statutory period may obtain title thereto under the principle of adverse possession. Edie v. Coleman, 235 Mo. App. 1289, 141 S.W. 2d 238 (1940), Vade v. Sickler, 118 Colo. 236, 195 P.2d 390 (1948). -

Eviction Notice in Real Estate

Eviction Notice In Real Estate Niall never ventilate any hards conjured rhetorically, is Hans-Peter stretching and charming enough? When Shelden jig his nominalists nitrogenised not molto enough, is Perry errhine? Unimpressive Valdemar sometimes misclassified his cicatrization stodgily and traduces so ventrally! It the eviction notice The name, Deportation, each court counts days differently! The writ of possession is the brass ring every landlord grabs for when a landlord brings a tenant to eviction court. Pay Rent or Quit Notice, the tenant must follow the due process. Just Got an Eviction Notice? First step is to file the Prejudgment Claim with the Court. Over the years, on time, but inform the tenant in writing upon acceptance that by accepting the partial payment you do not waive your right to proceed with the eviction. Need help figuring out your defenses? What if course do than move but after I correct an eviction notice Improper notice defense Unsafe or unfit housing defense Retaliation defense Discrimination defense Will. Although he has a very busy practice, but some bad actors are drawing FTC attention. This sample house rental agreement template specifies the following details: Contact details of both parties; property, or if the parties cannot come to an agreement to fix the damage, we can help. What is the California Eviction Process? It can be frustrating to have to become familiar with each set of laws, like Arizona, and order me to leave? You always need to be prepared for the possibility of going one or three months without rent as you work through the eviction process. -

EVICTION for TENANTS an Informational Guide to a North Dakota Civil Court Process

EVICTION FOR TENANTS An Informational Guide to a North Dakota Civil Court Process The North Dakota Legal Self Help Center provides resources to people who represent themselves in civil matters in the North Dakota state courts. The information provided in this informational guide isn’t intended for legal advice but only as a general guide to a civil court process. If you decide to represent yourself, you’ll need to do additional research to prepare. When you represent yourself, you’re expected to know and follow the law, including: • State or federal laws that apply to your case; • Case law, also called court opinions, that applies to your case; and • Court rules that apply to your case, which may include: o North Dakota Rules of Civil Procedure; o North Dakota Rules of Court; o North Dakota Rules of Evidence; o North Dakota Administrative Rules and Orders; o Any local court rules. Links to the laws, case law, and court rules can be found at www.ndcourts.gov. A glossary with definitions of legal terms is available at www.ndcourts.gov/legal-self-help. When you represent yourself, you’re held to same requirements and responsibilities as a lawyer, even if you don’t understand the rules or procedures. If you’re unsure if this information suits your circumstances, consult a lawyer. • If you would like to learn more about finding a lawyer to represent you, go to www.ndcourts.gov/legal-self-help/finding-a-lawyer. This information isn’t a complete statement of the law. This covers basic information about the process of eviction in a North Dakota State District Court from a tenant’s perspective. -

Tenants & Landlords

A Practical Guide for Tenants & Landlords Dear Friend: This booklet is designed to inform tenants and landlords about their rights and responsibilities in rental relationships. It serves as a useful reference—complete with the following: › An in-depth discussion about rental-housing law in an easy-to-read question- and-answer format; › Important timelines that outline the eviction process and recovering or keeping a security deposit; › A sample lease, sublease, roommate agreement, lead-based paint disclosure form, and inventory checklist; › Sample letters about repair and maintenance, termination of occupancy, and notice of forwarding address; and › Approved court forms. Whether you are a tenant or a landlord, when you sign a lease agreement, you sign a contract. You are contractually obligated to perform certain duties and assume certain responsibilities. You are also granted certain rights and protections under the lease agreement. Rental-housing law is complex. I am grateful to the faculty and students of the MSU College of Law Housing Law Clinic for their detailed work and assistance in compiling the information for this booklet. Owners of mobile-home parks, owners of mobile homes who rent spaces in the parks, and renters of mobile homes may have additional rights and duties. Also, landlords and renters of subsidized housing may have additional rights and duties. It is my pleasure to provide this information to you. I hope that you find it useful. MSU College of Law Housing Law Clinic (517) 336-8088, Option 2 [email protected] www.law.msu.edu/clinics/rhc This informational booklet is intended only as a guide— it is not a substitute for the services of an attorney and is not a substitute for competent legal advice.