Copyright by Nathaniel Andrew Rossi 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Center Presents Downtown LA's Largest July 4Th

Contact: Bonnie Goodman FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For Grand Park 213-308-9539 direct [email protected] The Music Center Presents Downtown LA’s Largest July 4th Celebration with Grand Park’s 4th of July Block Party – Free Blockbuster Event Will Light Up the Sky from the Rooftops Surrounding Grand Park – LOS ANGELES (June 3, 2015) – Angelenos will take over the civic center as they come together for an LA-style July 4th celebration at the third annual Grand Park’s 4th of July Block Party, presented by The Music Center. The free event, which runs from 3:00 p.m. – 9:30 p.m. on Saturday, July 4, 2015, will feature music, art, dancing, food, family, friends and fireworks for a feel-good, hometown event unlike any other Downtown LA has seen. Grand Park will light up the civic center skyline with a new, first-ever rooftop fireworks display set to iconic American music. The block party will be spread over eight city blocks, from Temple Street to 2nd Street, and from Grand Avenue to Main Street. Grand Park’s Fourth of July Block Party is supported by the County of Los Angeles, City Councilmember José Huizar, Bank of America and KCRW. During the block party, Grand Park’s green spaces will be transformed into giant picnic areas, while two dedicated stages – THE FRONT YARD on Grand Park’s Performance Lawn between Grand Avenue and Hill Street and THE BACKYARD on Grand Park’s Event Lawn between Broadway and Spring Street – will showcase a diverse lineup of LA-based musical artists, dancers, jump rope experts and spoken word artists. -

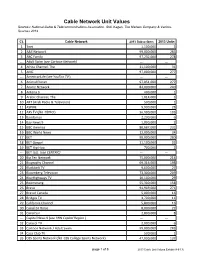

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, the Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, The Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013 Ct. Cable Network 2013 Subscribers 2013 Units 1 3net 1,100,000 3 2 A&E Network 99,000,000 283 3 ABC Family 97,232,000 278 --- Adult Swim (see Cartoon Network) --- --- 4 Africa Channel, The 11,100,000 31 5 AMC 97,000,000 277 --- AmericanLife (see YouToo TV ) --- --- 6 Animal Planet 97,051,000 277 7 Anime Network 84,000,000 240 8 Antena 3 400,000 1 9 Arabic Channel, The 1,014,000 3 10 ART (Arab Radio & Television) 500,000 1 11 ASPIRE 9,900,000 28 12 AXS TV (fka HDNet) 36,900,000 105 13 Bandamax 2,200,000 6 14 Bay News 9 1,000,000 2 15 BBC America 80,687,000 231 16 BBC World News 12,000,000 34 17 BET 98,000,000 280 18 BET Gospel 11,100,000 32 19 BET Hip Hop 700,000 2 --- BET Jazz (see CENTRIC) --- --- 20 Big Ten Network 75,000,000 214 21 Biography Channel 69,316,000 198 22 Blackbelt TV 9,600,000 27 23 Bloomberg Television 73,300,000 209 24 BlueHighways TV 10,100,000 29 25 Boomerang 55,300,000 158 26 Bravo 94,969,000 271 27 Bravo! Canada 5,800,000 16 28 Bridges TV 3,700,000 11 29 California Channel 5,800,000 16 30 Canal 24 Horas 8,000,000 22 31 Canal Sur 2,800,000 8 --- Capital News 9 (see YNN Capital Region ) --- --- 32 Caracol TV 2,000,000 6 33 Cartoon Network / Adult Swim 99,000,000 283 34 Casa Club TV 500,000 1 35 CBS Sports Network (fka CBS College Sports Network) 47,900,000 137 page 1 of 8 2013 Cable Unit Values Exhibit (4-9-13) Ct. -

2013 Post Hispanic Upfront Television Guide a Digital Supplement to Broadcasting & Cable and Hispanicad.Com

2013 post hispanic upfront television guide a digital supplement to broadcasting & cable and hispanicad.com With Drop Shadow Published by: Without Drop Shadow For Black Background For Black & White in color For Black & White in color For Black & White in white mcn_standard.indd 3 5/15/2013 8:29:52 PM Q A THE QUEST TO& CLOSE THE AD GAP UNIVISION’S CESAR CONDE BELIEVES HISPANIC TELEVISION WILL CONTINUE TO GROW. CONVINCING CLIENTS TO PARTICIPATE REMAINS AN INDUSTRY FRUSTRATION. Univision Networks president Cesar Conde is excited about the attention Spanish- language television—and forthcoming English-language offerings targeting Latinos— is getting from the mainstream media. In this Q&A with Adam R Jacobson, Conde discusses his network’s plans for 2013, including its digital initiatives and the vital importance of research in making the proper programming decisions across all screens. Spanish-language Adam R Jacobson: Cesar Conde: As evidenced by the have witnessed rst-hand the power of television conti nues to att ract the lion’s number of new Hispanic o erings Spanish-language media. e challenge share of Hispanic adverti sing dollars, cropping up across the media industry for us all is to close the ad gap. and new networks have emerged in the these days, the size, importance and last year—namely MundoFox, Univision Univision seems to be a in uence of the U.S. Hispanic community ARJ: Deportes, TLNovelas, and the revamped communicati ons company in is nally receiving the widespread NuvoTV. It’s clear that the thirst for transformati on, with TeleFutura acknowledgement it deserves. -

Un Dia Nos Volveremos

DIRECTORIO LIC. JAVIER CORRAL JURADO Gobernador Constitucional del Estado de Chihuahua DR. VÍCTOR QUINTANA SILVEYRA Secretario de Desarrollo Social del Gobierno del Estado de Chihuahua. LIC. EMMA SALDAÑA LOBERA Directora General del Instituto Chihuahuense de las Mujeres LIC. JESÚS ANTONIO PINEDO CORNEJO Coordinador de Comunicación Social PRESENTACIÓN Nuestra sociedad se encuentra lastimada, caracterizada por altos índices de violencia contra las mujeres y por un machismo recalcitrante que aún permea en la entidad, aspectos que han traído como consecuencia la diseminación de un cáncer que daña lo más profundo de la dignidad colectiva. Ante dicho escenario, el respeto y garantía de los Derechos Humanos es un enfoque prioritario y transversal de nuestra administración, cuya obligación ha sido, además, generar una alianza con la sociedad civil a fin de garantizar una debida respuesta a las víctimas y familiares de la violencia contra las mujeres. Es menester del trabajo institucional privilegiar en sus objetivos el empoderamiento de las víctimas y dentro de su esfuerzo por lograr la reparación integral, sobresale la necesidad de buscar la reparación colectiva. De ahí la importancia de esta compilación de historias de vida, la cual corresponde a la deuda histórica que se tiene con las familias, para reconocer y hacer notar, lejos de frías estadísticas, el cúmulo de huellas que dejaron las mujeres a quienes despiadadamente se les arrebató su vida. Conocer de ellas, reconocerlas como parte importante de nuestra sociedad, reflejarnos en su vida, en sus anhelos y en sus actividades diarias, visualizar las cicatrices que contribuyan a fortalecernos y a solidarizarnos, debe llevar a construirnos en una gran comunidad de justicia y de paz, con la que soñamos. -

Comcast Xfinity Tv

Channel Comparison Hunters Ridge COMCAST XFINITY TV Prism™ Complete DIGITAL STARTER DIGITAL FAVORITES Common Name Key # Channel Name # Channel Name # Channel Name 24 hour 15 24 Hours News and Weather (WINKDT2) A&E 166 A&E General AETV 50 A&E 95 A&E A&E HD 1166 A&E HD PrismTV General AETVHD 410 A&E HD 488 A&E HD ABC (WZVN) 7 ABC (WZVN) Local WZVN 7 ABC (WZVN) 6 ABC 7 WZVN ABC (WZVN) HD 1007 ABC HD (WZVNDT) PrismTV 431 ABC (WZVN) HD 406 ABC 7 WZVN HD ABC FAMILY 178 ABC Family Family ABCF 46 ABC FAMILY 62 ABC Family ABC FAMILY HD 1178 ABC Family HD PrismTV Family ABCFHD 444 ABC FAMILY HD 432 ABC Family HD AccuWeather 27 AccuWeather AMC 795 AMC Movies AMC 53 AMC 84 AMC AMC HD 1795 AMC HD PrismTV Movies AMCHD 429 AMC HD 479 AMC HD American Heroes 259 American Heroes Channel Educational AHC American Heroes Channel HD Educational 1259 American Heroes HD AHCHD ANIMAL PLANET 252 Animal Planet Educational APL 68 ANIMAL PLANET 61 ANIMAL PLANET ANIMAL PLANET HD 1252 Animal Planet HD Educational APLHD 426 ANIMAL PLANET HD 420 ANIMAL PLANET HD AXS TV HD 1105 AXS TV PrismTV Movies AXSTV 493 AXS TV HD AZTECA AMERICA (WANA) 231/611 AZTECA AMERICA (WANA) BABY FIRST 310 Baby First TV Family BABY1 BBC AMERICA 188 BBC America General BBCA 114 BBC AMERICA 51 BBC AMERICA BBC America HD 1188 BBC America HD General BBCAHD BBC WORLD 115 BBC WORLD BEIN SPORTS 214 belN Sports BEIN SPORTS HD 502 belN Sports HD BEIN SPORTS Espanol BET 155 BET General BET 22 BET 85 BET BET GOSPEL 114 BET GOSPEL BET HD 1155 BET HD PrismTV General BETHD 475 BET HD 499 BET HD BLOOMBERG -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

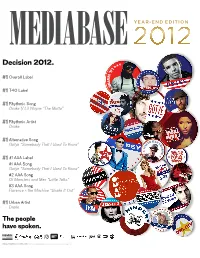

Decision 2012

YEAR-END EDITION MEDIABASE 2012 Decision 2012. #1 Overall Label #1 T40 Label #1 Rhythmic Song Drake f/ Lil Wayne “The Motto” #1 Rhythmic Artist Drake Alternative Song #1 HAW ER T Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” Y H A O M R N H E H #1 #1 AAA Label #1 AAA Song Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” #2 AAA Song Of Monsters and Men “Little Talks” #3 AAA Song Florence + the Machine “Shake It Out” #1 Urban Artist Drake The people have spoken. www.republicrecords.com c 2012 Universal Republic Records, a Division of UMG Recordings, Inc. REPUBLIC LANDS TOP SPOT OVERALL Republic Top 40 Champ Island Def Jam Takes Rhythmic & Urban Republic t o o k t h e t o p s p o t f o r t h e 2 0 1 2 c h a r t y e a r, w h i c h w e n t f r o m N o v e m b e r 2 0 , 2 0 1 1 - N o v e m b e r 17, 2012. The label was also #1 at Top 40 and Triple A, while finishing #2 at Rhythmic, #3 at Urban, and #4 at AC. Their overall share was 13.5%. Leading the way for Republic was newcomer Gotye, who had one of the year’s biggest hits with “Somebody That I Used To Know.” A big year from Drake and Nicki Minaj also contributed to the label’s success, as well as strong performances for Florence + The Machine, Volbeat, and Of Monsters And Men to name a few. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/09/2016 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/09/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Crazy - Patsy Cline Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Don't Stop Believing - Journey Love Yourself - Justin Bieber Shake It Off - Taylor Swift Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond My Girl - The Temptations Like I'm Gonna Lose You - Meghan Trainor Girl Crush - Little Big Town Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Ex's & Oh's - Elle King Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Let It Go - Idina Menzel Me Too - Meghan Trainor Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-a-Lot EXPLICIT Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals H.O.L.Y. - Florida Georgia Line Hello - Adele Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd When We Were Young - Adele Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Jackson - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Summer Nights - Grease Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Can't Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Piano Man - Billy Joel I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys All Of Me - John Legend Turn The Page - Bob Seger These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley My Way - Frank Sinatra (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's 7 Years - Lukas Graham Wannabe - Spice Girls A Whole New World - -

See TV in a Whole

1505 MTV2 HD 1856 Showtime Showcase HD (E) NEW 3128 De Película NEW 1045 My Network TV HD (KUTPDT) 1857 Showtime Showcase HD (W) NEW 3129 De Película Clásico NEW 1172 MyDestination.TV HD NEW 1866 Showtime Women HD (E) NEW 3102 Discovery en Espanol 1264 NASA TV HD NEW 1867 Showtime Women HD (W) NEW 3103 Discovery Familia 1267 Nat Geo WILD HD NEW 1118 Smithsonian Channel HD (E) NEW 3051 Disney en Espanol 1266 National Geographic Channel HD 1119 Smithsonian Channel HD (W) NEW 3052 Disney XD Espanol See TV in a whole 1012 NBC HD (KPNXDT) 1791 Sony Movie Channel HD NEW 3302 ESPN Deportes 1640 NBC Sports HD 1146 Spike TV HD 3077 EWTN en Espanol 1630 NFL Network HD 1642 Sportsman Channel HD 3303 FOX Deportes 1629 NFL RedZone HD (Pay Per View) 1337 Sprout HD 3304 GolTV 1638 NHL Network HD 1908 Starz! Cinema HD (E) NEW 3104 History en Espanol 1314 Nickelodeon HD 1904 Starz! Edge HD NEW 3056 La Familia Cosmovision 1185 NUVOtv HD NEW 1902 Starz! HD (E) NEW 3017 Latele Novela 1209 One America News HD NEW 1903 Starz! HD (W) NEW 3149 Ritmoson Latino NEW 1256 Oprah Winfrey Network HD 1906 Starz! In Black HD NEW 3078 TBN Enlace 1680 Outdoor Channel HD 1912 Starz! Kids and Family HD NEW 3143 TeleHit NEW 1844 OuterMAX HD 1931 Starz! On Demand 3024 TV Chile 1678 Outside TV HD NEW 1152 Syfy HD 3020 Video Rola 1531 Ovation HD 1113 TBS HD 3013 WAPA America 1368 Oxygen HD 1039 Telemundo HD (KTAZDT) 1683 PAC-12 Arizona HD NEW 1006 The CW HD (KASWDT) 1684 PAC-12 Bay Area HD NEW 1335 The Hub HD International Channels 1685 PAC-12 Los Angeles HD NEW 1225 The Weather -

Channel Lineup

632 Centroamérica TV 314 The Movie Channel HD^^ Pay-Per-View 633 TBN-Enlace USA 533 Starz 634 BabyFirst Americas (en 535 Starz Edge 440-449 TEAM PPV Español) 537 Starz in Black 450 TEAMHD PPV^^ 636 Discovery Familia 538 Starz Cinema 459 GAMEHD2 PPV^^ 637 EWTN Español 539 Starz Kids & Family 460 GAMEHD PPV^^ 639 Univision West 540 Starz Comedy 461-470 GAME PPV 640 Pasiones 543 Playboy TV 477-480 GAME PPV 641 Once Mexico 550 HBO East 829 iN DEMAND HD PPV^^ 642 Vme Kids 551 HBO West 830-832 iN DEMAND PPV 643 Sur Peru 552 HBO 2 833-838 ESPN Sports PPV 644 TV Dominicana 554 HBO Signature 840 TEN 646 Telefe Internacional 556 HBO Family 841 Xtsy 647 Utilísima 558 HBO Latino 842 Playboy TV 648 CBTV Michoacan 559 HBO Comedy 844 Real 649 HITN-TV 560 HBO Zone 845 Penthouse TV 650 WAPA America 561 Cinemax West 651 TVE Internacional 562 Cinemax East Channel Lineup 652 TeleHit 564 MoreMax 653 Ritmoson 566 ActionMax 654 Bandamax 567 5StarMAX 655 De Pelicula 575 Showtime Effective January 2013 656 De Pelicula Clásico 577 Showtime Too 579 Showtime Showcase MultiLatino Max 581 Showtime Extreme 583 Showtime Next Only available as a component of 584 Showtime FamilyZone MultiLatino Max and Ultra packages 585 Showtime Women and includes the following channels: 586 FLIX BBC America, Bravo, ESPN, ESPN 590 The Movie Channel 2, Galavisión (where available), 592 The Movie Channel Xtra The Golf Channel, Lifetime Movie Network, MTV, NBC Sports Network, International Premium Services Nickelodeon, PBS KIDS Sprout, Comcast SportsNet Chicago, Spike 427/683 NEO Cricket (Indian) TV, Syfy, TBS, TLC, TNT, VH1 and, 660 ABP News where available, the corresponding 661 Life OK HD channels for these networks. -

Paulina Rubio

® Visítanos también en internet ociolatino.com OCIOYMáS Más de UN MILLÓN de visitas a nuestras secciones: GUIA DEL OCIO LATINO con todos los locales latinos OCIO LATINO TELEVISIÓN con vídeos de la colonia latina, OCIO LATINO RADIO sólo música y sin interferencias OcioLatino AÑO XVI • Nº 311 • OCTUBRE Primera agencia de colocación laboral GALERIA DE FOTOS Oficina Central: Tel.: 91 477 14 79 Correo Electrónico: [email protected] Manpower ha obtenido la autorización que empleo autonómicos. de nuestra gente Web Site: www.ociolatino.com concede el Ministerio de Trabajo e La autorización permite a Manpower des- para descargarlas y compartirlas Inmigración para trabajar como agencia de arrollar su labor de intermediación en todas Edita : DISEÑO LATINOAMERICANO S.L. C/ Puerto de Suebe, 13 - local 28038 Madrid colocación en toda España y realizará las comunidades autónomas y, según ha FACEBOOK Dirección: José Luis Salvatierra Dirección Publicitaria: labores de intermediación en el mercado señalado la directora general de la agencia Para hacer amigos Nilton López Ubilla Jefe de Redacción: Yolanda Vaccaro laboral para el sector público. de colocación de Manpower, Dolors Departamento Comercial: Nilton López (Madrid) Juan Zeña La empresa es el primer grupo de Poblet, el objetivo es “tener actividad en CONSULTA JURIDICA (Madrid) Carlos Pucutay (Barcelona) Manuel López (Barcelona) Soluciones de Recursos Humanos que todas ellas” ya que están preparados para Para asesoría gratuita Colaboran: Profesor Mércury, Ricardo Serrano. Félix Lam Distribuye: Flash Latina obtiene autorización como Agencia de dar cobertura en todo el país. ACTUALIDAD Depósito Legal: M1081/1998 ISSN 1138848 Colocación. La empresa dispone de instalaciones y con información diaria OCIO LATINO es una marca registrada en la Oficina Española de Patentes y Los servicios de Manpower como agencia recursos en Madrid, Cataluña, Aragón, Marcas con el Nº 2.087.283-6. -

SPAANS Artiest Titel 1940S Standards Bésame Mucho (Spanish Vocal) 1950S Standards Quien Sera (Sway) ABBA Chiquitita (Spanish Ve

SPAANS Artiest Titel 1940s Standards Bésame mucho (Spanish Vocal) 1950s Standards Quien Sera (Sway) ABBA Chiquitita (Spanish version) Aitana Ocaña & Ana Guerra Lo malo Alabina Alabina Aladdin Un mundo ideal Alaska ¿A quién le importa? Alaska & Los Pegamoides Bailando Alberto Cortez El vagabundo Alejandra Guzmán Soy solo un secreto Alejandro Fernández Te voy a perder Alejandro Fernández Se me va la voz Alejandro Fernández Me estoy enamorando Alejandro Fernández Eres Alejandro Lerner Todo a pulmón Alejandro Lerner No hace falta que lo digas Alejandro Lerner Amarte Asi Alejandro Sanz Tú no tienes alma Alejandro Sanz Desde cuando Alejandro Sanz Corazón partío Alejandro Sanz Aprendiz Alejandro Sanz feat. Marc Anthony Deja que te bese Álex Ubago Siempre en mi mente Álex Ubago Dame tu aire Álex Ubago A gritos de esperanza Álex Ubago feat. OBK Dime si no es amor Alfred García & Amaia Romero (Eurovision) Tu canción Álvaro Soler Sofia Álvaro Soler Libre (feat. Emma Marrone) Álvaro Soler La Cintura Álvaro Soler El mismo sol Álvaro Soler Animal Álvaro Soler feat. Morat Yo contigo, tù conmigo Álvaro Soler feat. Paty Cantú Libre Amaia Montero Caminando Amaral Mi alma perdida Ana Belén & David San José Cuéntame Ana Torroja in duet with Aleks Syntek Duele el amor Andrea Bocelli Bésame mucho Andrea Bocelli feat. Chris Botti Contigo en la distancia Andrea Bocelli feat. Jennifer Lopez Quizás, quizás, quizás Andrea Bocelli in duet with Laura Pausini Vive Ya Andrea Bocelli in duet with Marta Sanchez Vivo por ella Antonio Banderas & Los Lobos Canción Del Mariachi (Morena De Mi Corazón) Antonio Carmona feat. Alejandro Sanz Para que tú no llores Antonio José feat.