O:\CIVIL\Wyeth V. Mylan\Markman Hearing\Markman Order 5.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Responding to Mylan's Inadequate Tender Offer

Responding To Mylan’s Inadequate Tender Offer: Perrigo’s Board Recommends That You Reject the Offer and Do Not Tender September 2015 Important Information Forward Looking Statements Certain statements in this presentation are forward-looking statements. These statements relate to future events or the Company’s future financial performance and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors that may cause the actual results, levels of activity, performance or achievements of the Company or its industry to be materially different from those expressed or implied by any forward-looking statements. In some cases, forward-looking statements can be identified by terminology such as “may,” “will,” “could,” “would,” “should,” “expect,” “plan,” “anticipate,” “intend,” “believe,” “estimate,” “predict,” “potential” or other comparable terminology. The Company has based these forward-looking statements on its current expectations, assumptions, estimates and projections. While the Company believes these expectations, assumptions, estimates and projections are reasonable, such forward-looking statements are only predictions and involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties, many of which are beyond the Company’s control, including future actions that may be taken by Mylan in furtherance of its unsolicited offer. These and other important factors, including those discussed under “Risk Factors” in the Perrigo Company’s Form 10-K for the year ended June 27, 2015, as well as the Company’s subsequent filings with the Securities and Exchange -

Print Layout 1

TECHNICAL PROGRAM Monday, March 19 5:00 – 8:00 pm Welcome Reception Tuesday, March 20 8:00 – 10:00 Session 1: Setting the Conference Context and Drivers Chair: Geoff Slaff (Amgen) Roger Perlmutter (Amgen) Conquering the Innovation Deficit in Drug Discovery Helen Winkle (CDER, FDA) Regulatory Modernization 10:00 – 10:30 Break Vendor and poster review 10:30 – 12:30 Session 2: Rapid Cell Line Development and Improved Expression System Development Chairs: Timothy Charlebois (Wyeth) and John Joly (Genentech) Amy Shen (Genentech) Stable Antibody Production Cell-Line Development with an Improved Selection Process and Accelerated Timeline Mark Leonard (Wyeth) High-Performing Cell-Line Development within a Rapid and Integrated Platform Process Control Pranhitha Reddy (Amgen) Applying Quality-by-Design to Cell Line Development Lin Zhang (Pfizer) Development of a Fully-Integrated Automated System for High-Throughput Screening and Selection of Single Cells Expressing Monoclonal Antibodies 12:30 – 2:00 Lunch Vendor and poster review 2:00 – 4:30 Session 3: High-Throughput Bulk Process Development Chairs: Brian Kelley (Wyeth) and Jorg Thommes (Biogen Idec) Colette Ranucci (Merck) Development of a Multi-Well Plate System for High-Throughput Process Development Min Zhang (SAFC Biosciences) CHO Media Library – an Efficient Platform for Rapid Development and Optimization of Cell Culture Media Supporting High Production of Pharmaceutical Proteins in Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells Nigel Titchener-Hooker The Use of Ultra-Scale-Down Approaches to Enable Rapid Investigation -

Pfizer and Mylan Will Own 57% and 43% of the New Company (“Newco”), Respectively

DEAL PROFILE PFIZER | MYLAN VALUES 57% 43% $12.0bn PFIZER SHARE OF NEWCO MYLAN SHARE OF NEWCO NEW DEBT RAISED Pfizer Inc. (NYSE:PFE) Pfizer Inc. (“Pfizer”) is a pharmaceutical company that develops, manufactures, and sells products in internal medicine, vaccines, oncology, inflammation & immunology, and rare diseases. Upjohn, a subsidiary of Pfizer, is composed of Pfizer’s oral solid generics and off-patent drugs franchise, such as Viagra, Lipitor, and Xanax. Upjohn has a strong focus in emerging markets, and is headquartered in Shanghai, China. TEV: $265.4bn LTM EBITDA: $22.5bn LTM Revenue: $55.7bn Mylan N.V. (NASDAQ:MYL) Mylan N.V. (“Mylan”) is a pharmaceutical company that develops, manufactures, and commercializes generic, branded-generic, brand-name, and over-the-counter products. The company focuses in the following therapeutic areas: cardiovascular, CNS and anesthesia, dermatology, diabetes and metabolism, gastroenterology, immunology, infectious disease, oncology, respiratory and allergy, and women’s health. Mylan was founded in 1961 and is headquartered in Canonsburg, PA. TEV: $23.9bn LTM EBITDA: $3.5bn LTM Revenue: $11.3bn Bourne Partners provides strategic and financial advisory services to BOURNE clients throughout the business evolution life cycle. In order to provide PARTNERS the highest level of service, we routinely analyze relevant industry MARKET trends and transactions. These materials are available to our clients and partners and provide detailed insight into the pharma, pharma services, RESEARCH OTC, consumer health, and biotechnology sectors. On July 29, 2019, Pfizer announced the spin-off of its off-patent drug unit, Upjohn, in order to merge the unit with generic drug manufacturer, Mylan. -

Mylan Signs Agreement with Gilead to Enhance Access to Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF)- Based HIV Treatments in Developing Countries

December 1, 2014 Mylan Signs Agreement with Gilead to Enhance Access to Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF)- based HIV Treatments in Developing Countries PITTSBURGH and HYDERABAD, India, Dec. 1, 2014 /PRNewswire/ -- Mylan Inc. (Nasdaq: MYL) today announced that its subsidiary Mylan Laboratories Limited has entered into an agreement with Gilead Sciences, Inc. under which Mylan has licensed the non-exclusive rights to manufacture and distribute Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) as both a single agent product and in combination with other drugs. Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) is an investigational antiretroviral drug for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. The license being granted to Mylan extends to 112 countries, which together account for more than 30 million people living with HIV, representing 84% of those infected globally.1 Mylan CEO Heather Bresch said, "Mylan's mission is to provide the world's 7 billion people access to high quality medicines and set new standards in health care. By working with partners like Gilead to help ensure access to innovative new products such as Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) in the countries hardest hit by this disease, we can help stem the tide of HIV/AIDS around the world." As part of the licensing agreement, on U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, Mylan will receive a technology transfer from Gilead, enabling the company to manufacture low-cost versions of Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF), if approved as a single agent or in approved combinations containing Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) for developing markets. Phase III trials by Gilead Sciences met their primary objective supporting the potential for Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) to provide a new treatment option for individuals living with HIV. -

Moderna Vaccine Day Presentation

Zika Encoded VLP mRNA(s) RSV CMV + EBV SARS-CoV- RSV-ped 2 Flu hMPV/PIV3 H7N9 Encoded mRNA(s) Ribosome Protein chain(s) First Vaccines Day April 14, 2020 © 2020 M oderna Therapeutics Forward-looking statements and disclaimers This presentation contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, as amended including, but not limited to, statements concerning; the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the Company’s clinical trials and operations; the timing and finalization of a dose-confirmation Phase 2 study and planning for a pivotal Phase 3 study for mRNA-1647; the status and outcome of the Phase 1 clinical trial for mRNA-1273 being conducted by NIH; the next steps and ultimate commercial plan for mRNA-1273; the size of the potential market opportunity for mRNA-1273; the size of the potential commercial market for novel vaccines produced by Moderna or others; the potential peak sales for the Company’s wholly-owned vaccines; the probability of success of the Company’s vaccines individually and as a portfolio; and the ability of the Company to accelerate the research and development timeline for any individual product or the platform as a whole. In some cases, forward-looking statements can be identified by terminology such as “will,” “may,” “should,” “expects,” “intends,” “plans,” “aims,” “anticipates,” “believes,” “estimates,” “predicts,” “potential,” “continue,” or the negative of these terms or other comparable terminology, although not all forward-looking statements contain these words. The forward-looking statements in this press release are neither promises nor guarantees, and you should not place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements because they involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other factors, many of which are beyond Moderna’s control and which could cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed or implied by these forward-looking statements. -

Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc., a Subsidiary of Pfizer Inc Mylotarg

Mylotarg FDA ODAC Briefing Document 11 July 2017 WYETH PHARMACEUTICALS INC., A SUBSIDIARY OF PFIZER INC MYLOTARG (gemtuzumab ozogamicin; PF-05208747) In combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of previously untreated de novo CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia and as monotherapy for the treatment of CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse FDA ONCOLOGIC DRUGS ADVISORY COMMITTEE BRIEFING DOCUMENT (BLA 761060) Meeting Date: 11 July 2017 ADVISORY COMMITTEE BRIEFING MATERIALS: AVAILABLE FOR PUBLIC RELEASE 090177e18c1aa788\Approved\Approved On: 12-Jun-2017 13:05 (GMT) Page 1 Mylotarg FDA ODAC Briefing Document 11 July 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS...........................................................................................................2 LIST OF TABLES.....................................................................................................................5 LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................6 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................7 1.1. Introduction..............................................................................................................7 1.2. Rationale for Mylotarg Dosing Regimens ...............................................................8 1.3. Mylotarg in Patients With Previously Untreated De Novo AML............................9 1.4. Mylotarg in Patients With AML in First Relapse..................................................11 -

Merck & Co., Inc

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on February 25, 2021 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D. C. 20549 _________________________________ FORM 10-K (MARK ONE) ☒ Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ Transition Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 1-6571 _________________________________ Merck & Co., Inc. 2000 Galloping Hill Road Kenilworth New Jersey 07033 (908) 740-4000 New Jersey 22-1918501 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation) (I.R.S Employer Identification No.) Securities Registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol(s) Name of Each Exchange on which Registered Common Stock ($0.50 par value) MRK New York Stock Exchange 1.125% Notes due 2021 MRK/21 New York Stock Exchange 0.500% Notes due 2024 MRK 24 New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2026 MRK/26 New York Stock Exchange 2.500% Notes due 2034 MRK/34 New York Stock Exchange 1.375% Notes due 2036 MRK 36A New York Stock Exchange Number of shares of Common Stock ($0.50 par value) outstanding as of January 31, 2021: 2,530,315,668. Aggregate market value of Common Stock ($0.50 par value) held by non-affiliates on June 30, 2020 based on closing price on June 30, 2020: $195,461,000,000. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Fellow Shareholders, Since Perrigo Company

Fellow Shareholders, Since Perrigo Company plc (NYSE and TASE: PRGO) rejected Mylan N.V.’s (NASDAQ: MYL) unsolicited offer, I have spent a great deal of time speaking with our shareholders and sharing our views on why Mylan’s offer substantially undervalues Perrigo. We are confident in our bright prospects and firmly convinced of the standalone value of Perrigo. I have also engaged with you not only about value, but also about the right way to run a company. I have always believed that good corporate governance creates value for shareholders while bad corporate governance can destroy it. Since becoming the CEO of the Perrigo Company, I have had the privilege of working alongside a Board that shares my commitment to shareholder value creation and sound corporate governance. Together, we believe deeply in our responsibility to shareholders, who are Perrigo’s true owners, and in our obligation to build sustainable, long-term value, which informs everything we do. This commitment has rewarded Perrigo shareholders with a total return exceeding 970 percent since 2007. I have watched with increasing distress the contrast in attitude to shareholders and governance principles that Mylan has presented in its pursuit of Perrigo. Our Board has considered Mylan’s offer in good faith and we have been earnest and straightforward in explaining why we think it substantially undervalues Perrigo and creates significant risks. We have also engaged with you to explain how Perrigo’s ‘Base Plus, Plus, Plus’ strategy is poised to continue to create value in the future for our shareholders. In recent weeks, it has become clear to me that Mylan’s pursuit of Perrigo at all costs has further highlighted some very troubling corporate governance values. -

Amgen and Wyeth Statement on FDA Announcement About Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Blockers

Amgen and Wyeth Statement on FDA Announcement About Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Blockers August 4, 2009 THOUSAND OAKS, Calif. and COLLEGEVILLE, Pa., Aug. 4 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Amgen (Nasdaq: AMGN) and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, a division of Wyeth (NYSE: WYE), issued a statement in response to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announcement regarding the results of a safety review of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) blockers [marketed as Remicade (infliximab), Enbrel (etanercept), Humira (adalimumab), Cimzia (certolizumab pegol) and Simponi (golimumab)]. This safety review was the subject of an FDA Early Communication in June 2008 pertaining to cases of malignancy in pediatric patients exposed to a TNF blocker. As a result of this review, the FDA has required strengthened warnings about the occurrence of lymphoma and other cancers in children and young adults using these medicines. AMGEN AND WYETH STATEMENT: Amgen and Wyeth believe that ENBREL continues to offer a favorable benefit-risk relationship for patients with the diseases for which it is indicated to treat, including moderate to severe Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA). JIA can be a serious and potentially debilitating condition. Amgen will work with the FDA to update the U.S. Prescribing Information, and Medication Guide for ENBREL as described in the FDA communication which can be read at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm175803.htm. In addition, Amgen and Wyeth will communicate the revised product labeling to both physicians and patients. ENBREL was first approved for JIA in the U.S. in 1999. It is estimated through postmarketing data that approximately 13,847 pediatric patients have been treated with ENBREL globally through February 2009, accounting for approximately 44,600 patient-years of exposure. -

1:19-Cv-02226 Document #: 1 Filed: 04/01/19 Page 1 of 74 Pageid #:1

Case: 1:19-cv-02226 Document #: 1 Filed: 04/01/19 Page 1 of 74 PageID #:1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS WELFARE PLAN OF THE INTERNATIONAL UNION OF OPERATING ENGINEERS LOCALS 137, 137A, 137B, 137C, 137R, on behalf of itself Civil Action No.______________ and all others similarly situated, CLASS ACTION Plaintiff, v. JURY TRIAL DEMANDED ABBVIE INC., ABBVIE BIOTECHNOLOGY LTD, and AMGEN INC., Defendants. CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Case: 1:19-cv-02226 Document #: 1 Filed: 04/01/19 Page 2 of 74 PageID #:2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODCUTION ...............................................................................................................1 II. PARTIES .............................................................................................................................3 III. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ..........................................................................................5 IV. THE REGULATORY FRAMEWORK OF BIOLOGICS ..................................................6 A. Cost Concerns Prompt Congress to Enact the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act ..............................................................................6 1. New biologic drug approval under the BPCIA ............................................7 2. Biosimilar drug approval under the BPCIA .................................................8 3. Biosimilar entrants’ effect on marketplace ..................................................9 B. Patent Challenges Under the BPCIA .....................................................................11 -

Mvx List.Pdf

MVX_CODE manufacturer_name Notes status last updated date manufacturer_id AB Abbott Laboratories includes Ross Products Division, Solvay Inactive 16-Nov-17 1 ACA Acambis, Inc acquired by sanofi in sept 2008 Inactive 28-May-10 2 AD Adams Laboratories, Inc. Inactive 16-Nov-17 3 ALP Alpha Therapeutic Corporation Inactive 16-Nov-17 4 AR Armour part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 5 AVB Aventis Behring L.L.C. part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 6 AVI Aviron acquired by Medimmune Inactive 28-May-10 7 BA Baxter Healthcare Corporation-inactive Inactive 28-May-10 8 BAH Baxter Healthcare Corporation includes Hyland Immuno, Immuno International AG,and North American Vaccine, Inc./acquired somInactive 16-Nov-17 9 BAY Bayer Corporation Bayer Biologicals now owned by Talecris Inactive 28-May-10 10 BP Berna Products Inactive 28-May-10 11 BPC Berna Products Corporation includes Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute Berne Inactive 16-Nov-17 12 BTP Biotest Pharmaceuticals Corporation New owner of NABI HB as of December 2007, Does NOT replace NABI Biopharmaceuticals in this codActive 28-May-10 13 MIP Emergent BioSolutions Formerly Emergent BioDefense Operations Lansing and Michigan Biologic Products Institute Active 16-Nov-17 14 CSL bioCSL bioCSL a part of Seqirus Inactive 26-Sep-16 15 CNJ Cangene Corporation Purchased by Emergent Biosolutions Inactive 29-Apr-14 16 CMP Celltech Medeva Pharmaceuticals Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 17 CEN Centeon L.L.C. Inactive 28-May-10 18 CHI Chiron Corporation Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 19 CON Connaught acquired by Merieux Inactive 28-May-10 21 DVC DynPort Vaccine Company, LLC Active 28-May-10 22 EVN Evans Medical Limited Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 23 GEO GeoVax Labs, Inc. -

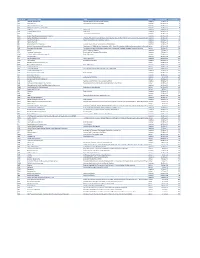

FDA Listing of Authorized Generics As of July 1, 2021

FDA Listing of Authorized Generics as of July 1, 2021 Note: This list of authorized generic drugs (AGs) was created from a manual review of FDA’s database of annual reports submitted to the FDA since January 1, 1999 by sponsors of new drug applications (NDAs). Because the annual reports seldom indicate the date an AG initially entered the market, the column headed “Date Authorized Generic Entered Market” reflects the period covered by the annual report in which the AG was first reported. Subsequent marketing dates by the same firm or other firms are not included in this listing. As noted, in many cases FDA does not have information on whether the AG is still marketed and, if not still marketed, the date marketing ceased. Although attempts have been made to ensure that this list is as accurate as possible, given the volume of d ata reviewed and the possibility of database limitations or errors, users of this list are cautioned to independently verify the information on the list. We welcome comments on and suggested changes (e.g., additions and deletions) to the list, but the list may include only information that is included in an annual report. Please send suggested changes to the list, along with any supporting documentation to: [email protected] A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V X Y Z NDA Applicant Date Authorized Generic Proprietary Name Dosage Form Strength Name Entered the Market 1 ACANYA Gel 1.2% / 2.5% Bausch Health 07/2018 Americas, Inc.