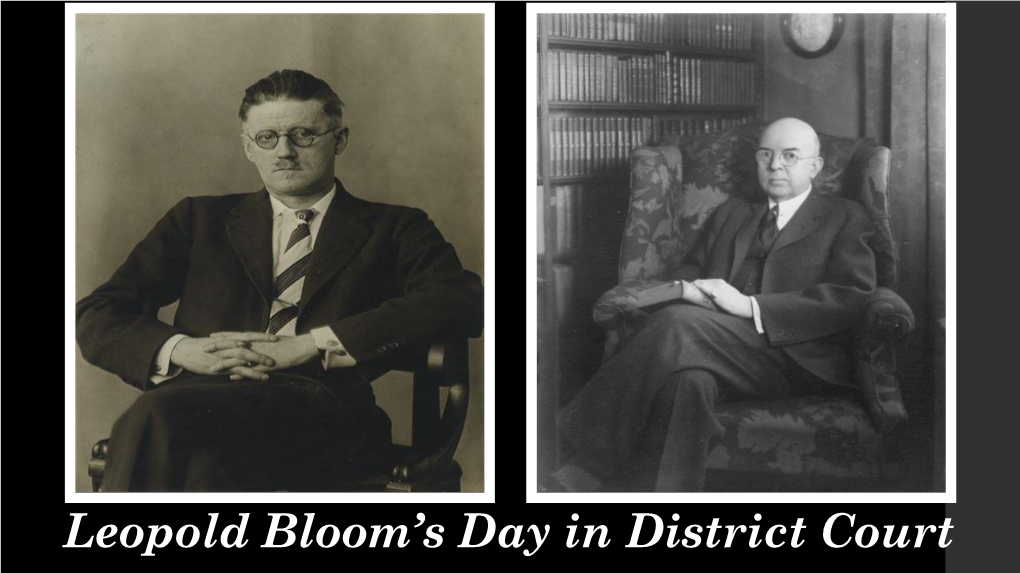

Leopold Bloom's Day in District Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1974.Ulysses in Nighttown.Pdf

The- UNIVERSITY· THEAtl\E Present's ULYSSES .IN NIGHTTOWN By JAMES JOYCE Dramatized and Transposed by MARJORIE BARKENTIN Under the Supervision of PADRAIC COLUM Direct~ by GLENN ·cANNON Set and ~O$tume Design by RICHARD MASON Lighting Design by KENNETH ROHDE . Teehnicai.Direction by MARK BOYD \ < THE CAST . ..... .......... .. -, GLENN CANNON . ... ... ... : . ..... ·. .. : ....... ~ .......... ....... ... .. Narrator. \ JOHN HUNT . ......... .. • :.·• .. ; . ......... .. ..... : . .. : ...... Leopold Bloom. ~ . - ~ EARLL KINGSTON .. ... ·. ·. , . ,. ............. ... .... Stephen Dedalus. .. MAUREEN MULLIGAN .......... .. ... .. ......... ............ Molly Bloom . .....;. .. J.B. BELL, JR............. .•.. Idiot, Private Compton, Urchin, Voice, Clerk of the Crown and Peace, Citizen, Bloom's boy, Blacksmith, · Photographer, Male cripple; Ben Dollard, Brother .81$. ·cavalier. DIANA BERGER .......•..... :Old woman, Chifd, Pigmy woman, Old crone, Dogs, ·Mary Driscoll, Scrofulous child, Voice, Yew, Waterfall, :Sutton, Slut, Stephen's mother. ~,.. ,· ' DARYL L. CARSON .. ... ... .. Navvy, Lynch, Crier, Michael (Archbishop of Armagh), Man in macintosh, Old man, Happy Holohan, Joseph Glynn, Bloom's bodyguard. LUELLA COSTELLO .... ....... Passer~by, Zoe Higgins, Old woman. DOYAL DAVIS . ....... Simon Dedalus, Sandstrewer motorman, Philip Beau~ foy, Sir Frederick Falkiner (recorder ·of Dublin), a ~aviour and · Flagger, Old resident, Beggar, Jimmy Henry, Dr. Dixon, Professor Maginni. LESLIE ENDO . ....... ... Passer-by, Child, Crone, Bawd, Whor~. -

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses Assistant Teacher Haider Ghazi Jassim AL_Jaberi AL.Musawi University of Babylon College of Education Dept. of English Language and Literature [email protected] Abstract Technically accounting, Intertextuality designates the interdependence of a literary text on any literary one in structure, themes, imagery and so forth. As a matter of fact, the term is first coined by Julia Kristeva in 1966 whose contention was that a literary text is not an isolated entity but is made up of a mosaic of quotations, and that any text is the " absorption, and transformation of another"1.She defies traditional notions of the literary influence, saying that Intertextuality denotes a transposition of one or several sign systems into another or others. Transposition is a Freudian term, and Kristeva is pointing not merely to the way texts echo each other but to the way that discourses or sign systems are transposed into one another-so that meanings in one kind of discourses are heaped with meanings from another kind of discourse. It is a kind of "new articulation2". For kriszreve the idea is a part of a wider psychoanalytical theory which questions the stability of the subject, and her views about Intertextuality are very different from those of Roland North and others3. Besides, the term "Intertextuality" describes the reception process whereby in the mind of the reader texts already inculcated interact with the text currently being skimmed. Modern writers such as Canadian satirist W. P. Kinsella in The Grecian Urn4 and playwright Ann-Marie MacDonald in Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet) have learned how to manipulate this phenomenon by deliberately and continually alluding to previous literary works well known to educated readers, namely John Keats's Ode on a Grecian Urn, and Shakespeare's tragedies Romeo and Juliet and Othello respectively. -

James Joyce and His Influences: William Faulkner and Anthony Burgess

James Joyce and His Influences: William Faulkner and Anthony Burgess An abstract of a Dissertation by Maxine i!3urke July, Ll.981 Drake University Advisor: Dr. Grace Eckley The problem. James Joyce's Ulysses provides a basis for examining and analyzing the influence of Joyce on selected works of William Faulkner and Anthony Bur gess especially in regard to the major ideas and style, and pattern and motif. The works to be used, in addi tion to Ulysses, include Faulkner's "The Bear" in Go Down, Moses and Mosquitoes and Burgess' Nothing Like the Sun. For the purpose, then, of determining to what de gree Joyce has influenced other writers, the ideas and techniques that explain his influence such as his lingu istic innovations, his use of mythology, and his stream of-consciousness technique are discussed. Procedure. Research includes a careful study of each of the works to be used and an examination of var ious critics and their works for contributions to this influence study. The plan of analysis and presentation includes, then, a prefatory section of the dissertation which provides a general statement stating the thesis of this dissertation, some background material on Joyce and his Ulysses, and a summary of the material discussed in each chapter. Next are three chapters which explain Joyce's influence: an introduction to Joyce and Ulysses; Joyce and Faulkner; and Joyce and Burgess. Thus Chapter One, for the purpose of showing how Joyce influences other writers, discusses the ideas and techniques that explain his influences--such things as his linguistic innovations, his use of mythology, and his stream-of consciousness method. -

The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2013 Getting on Nicely in the Dark: The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses Barbara Nelson The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Nelson, Barbara, "Getting on Nicely in the Dark: The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses" (2013). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 491. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/491 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GETTING ON NICELY IN THE DARK: THE PERILS AND REWARDS OF ANNOTATING ULYSSES By BARBARA LYNN HOOK NELSON B.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, 1983 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English The University of Montana Missoula, MT December 2012 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Associate Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School John Hunt, Chair Department of English Bruce G. Hardy Department of English Yolanda Reimer Department of Computer Science © COPYRIGHT by Barbara Lynn Hook Nelson 2012 All Rights Reserved ii Nelson, Barbara, M.A., December 2012 English Getting on Nicely in the Dark: The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses Chairperson: John Hunt The problem of how to provide useful contextual and extra-textual information to readers of Ulysses has vexed Joyceans for years. -

Advertising and Plenty in Joyce's Ulysses

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Fall 2009 All the Beef to the Heels Were in: Advertising and Plenty in Joyce's Ulysses Mindy Jo Ratcliff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ratcliff, Mindy Jo, "All the Beef to the Heels Were in: Advertising and Plenty in Joyce's Ulysses" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 175. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/175 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―All the beef to the heels were in‖: Advertising and Plenty in Joyce‘s Ulysses by MINDY JO RATCLIFF (Under the Direction of Howard Keeley) ABSTRACT Privileging a historicist approach, this document explores the presence of consumer culture, particularly advertising, in James Joyce‘s seminal modernist novel, Ulysses (1922). It interrogates Joyce‘s awareness of how a broad upswing in Ireland‘s post-Famine economy precipitated advertising-intensive consumerism in both rural and urban Ireland. Foci include the late-nineteenth-century transition in agriculture from arable farming to cattle-growing (grazier pastoralism), which, spurring economic growth, facilitated the emergence of a ―strong farmer‖ rural bourgeoisie. The thesis considers how Ulysses inscribes and critiques that relatively affluent coterie‘s expenditures on domestic cultural tourism, as well as hygiene-related products, whose presence on the Irish scene was complicated by a British discourse on imperial cleanliness. -

And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

“TWO NOTES IN ONE THERE”: COUNTERPOINT AS PARADIGM IN JAMES JOYCE’S ULYSSES by FRANCES VICTORIA LOVELACE (Under the Direction of Adam Parkes) ABSTRACT In this study of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) I discuss the limits and dangers of using analogies between musical and literary works without firmly understanding the musical model that is being brought into comparison with the novel in question. Conversely, I show that a musical paradigm such as counterpoint, if properly defined, can be a very useful method by which to read and understand Joyce, since the syntax of music is as important to (and ever- present within) the world of Ulysses as that of the English language. I demonstrate that a contrapuntal reading of the often-overlooked “Wandering Rocks” episode serves to uncover some darkly ironic questions about Anglo-Irish politics, and that while the fugal structure that Joyce claimed for “Sirens” is a deeply suspect analogy, a reading of the musical notation within the episode leads to a new understanding of Leopold Bloom in relation to his wife, Molly. INDEX WORDS: James Joyce, Music and Literature, Counterpoint “TWO NOTES IN ONE THERE”: COUNTERPOINT AS PARADIGM IN JAMES JOYCE’S ULYSSES by FRANCES VICTORIA LOVELACE BA, University of Warwick, UK, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2012 © 2012 Frances Victoria Lovelace All Rights Reserved “TWO NOTES IN ONE THERE”: COUNTERPOINT AS PARADIGM IN JAMES JOYCE’S ULYSSES by FRANCES VICTORIA LOVELACE Major Professor: Adam Parkes Committee: Aidan Wasley Elizabeth Kraft Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2012 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated with grateful thanks for all the support to my family and friends, especially Layne, Rowland, Maggie, Angela, Kalpen, Jamie, Katherine, and Christine. -

The Conscious and Unconscious Formation of Leopold Bloom's Identity in James Joyce's Ulysses

The Conscious and Unconscious Formation of Leopold Bloom's Identity in James Joyce's Ulysses Čakarević Kršul, Ivan Vid Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Rijeci, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:186:956407 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-24 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of the University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences - FHSSRI Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Ivan Vid Čakarević Kršul The Conscious and Unconscious Formation of Leopold Bloom’s Identity in James Joyce’s Ulysses Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the B.A. in English Language and Literature and German Language and Literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Doc. dr. sc. Aidan O'Malley Rijeka, September 2020 Abstract: Leopold Bloom, the protagonist of Janes Joyce Ulysses, is the modern Everyman by virtue of his mundaneness and hybridity. He is the son of a Hungarian Jewish immigrant and an Irish Protestant, and he has converted to Catholicism to marry the daughter of an Irish military officer and his Spanish wife. Bloom’s identity is nuanced. His religious beliefs are haphazard amalgamation of Judaism, Christianity and atheism; he considers himself to be simultaneously Irish and Jewish; and some of his fellow Dubliners try to constrain him to a Jewish identity informed by anti-Semitic attitudes that were very common throughout Europe in 1904. This thesis will examine how Bloom’s identity is consciously formed in the Lotus Eaters, Ithaca, Penelope and Cyclops episodes and how it is unconsciously formed in Circe by introducing Jung’s notions of archetypes and the collective origin of myths. -

Myth, Modernism and Mentorship: Examining François Fénelon's Influence on James Joyce's Ulysses by Robert Curran a Thesis

Myth, Modernism and Mentorship: Examining François Fénelon’s Influence on James Joyce’s Ulysses by Robert Curran A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Robert Curran ii Myth, Modernism and Mentorship: Examining Francois Fenelon’s Influence on James Joyce’s Ulysses by Robert Curran This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor, Dr. Julieann V. Ulin, Department of English, and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: 1/ u~ Jujjeann V. Ulin, Ph D. Thesis Advisor Mary FarftciFar/ci, Ph D. John C. Leeds, Ph D. Eric L. Berlatsky, Ph D. Chair, Department of English Heather Coltman, D.M.A. Dean, Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters crt is/a.ou,» Jpfborah L. Floyd, Ed.D. Date / Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express sincere gratitude to his committee members for all of their guidance and support. I am deeply indebted to my committee chair, Professor Ulin, whose mentorship made this thesis a reality. Professor Leeds provided me with an important understanding of literary criticism. I am indebted to Professor Faraci for igniting my passion for literature. The author is grateful for the help and assistance he received from the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, as well as from Florida Atlantic University’s Marvin and Sybil Weiner Spirit of America Collection. -

Empathy Across Gender Boundaries in James Joyce's Ulysses

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 2 2016 “See Ourselves as Others See Us”: Empathy Across Gender Boundaries in James Joyce’s Ulysses Madison V. Chartier Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chartier, Madison V. (2016) "“See Ourselves as Others See Us”: Empathy Across Gender Boundaries in James Joyce’s Ulysses," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 2 , Article 20. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol2/iss1/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “See Ourselves as Others See Us”: Empathy Across Gender Boundaries in James Joyce’s Ulysses Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank Dr. Lee Garver of Butler University’s Department of English for his editing assistance and guidance on the craft of this paper. This paper was inspired by Dr. Garver’s seminar on James Joyce’s Ulysses. This article is available in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol2/ iss1/20 BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 2 “SEE OURSELVES AS OTHERS SEE US”: EMPATHY ACROSS GENDER BOUNDARIES IN JAMES JOYCE’S ULYSSES MADISON V. CHARTIER, BUTLER UNIVERSITY MENTOR: LEE GARVER Abstract Many critics originally attacked James Joyce’s Ulysses for its dark representation of gender relations. -

PDQ Joyce Syllabus (OLLI Short, February 1-5, 2020)

PDQ Joyce Syllabus (OLLI Short, February 1-5, 2020) We will discuss and read aloud an abridged version of Ulysses consisting of the script of highlights previously used in 2016 for an OLLI Bloomsday reading (attached to home page of Bloomsday by OLLI website at https://sites.google.com/site/bloomsdaybyolli/home/bloomsday---2017). OBJECTIVE: The objective of this 5-class study group is to share the enjoyment of reading Janes Joyce’s Ulysses. Ulysses is certainly Joyce’s master work, although there is much to be said for just about everything that he wrote. SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE (HOPEFULLY): For people who have not read Ulysses, there will be some background about the author and his writing, and some direct experience of the book. It should be fun because Joyce was a genius with a fine sense of humor. The script of highlights that we will use provides a good sample of Ulysses, and a good way of getting into the book. For those already familiar with Joyce and Ulysses this is an opportunity to re-experience something pleasurable. It is remarkable that even upon multiple readings Ulysses always seems to present something new - passages that do not seem to have been present before or new interpretations, relationships or references. This is not surprising because the author purposely mined the book with ironic puzzles and riddles. In a sense reading and re-reading Ulysses is like reviewing the work of a mischievous poet. Our sampling of Ulysses is, of course, not a substitute for the entire book, and it is a challenge to choose highlights because there are many fine passages. -

James Joyce, Leopold Bloom and the Modernist Archetype

Papers on Joyce 10/11 (2004-2005): 143-62 “The Greatest Jew of All”: James Joyce, Leopold Bloom and the Modernist Archetype MORTON P. LEVITT Abstract Holding a veteran scholar’s reflection on the experience of rereading Ulysses over more than four decades, this paper examines the Jewishness of Leopold Bloom. The paper locates this Jewishness at the very heart of Bloom’s identity, bemused as it is by legal dismissals of authenticity, mildly riled by the citizen’s bigotry, troubled by the suicide of his father, and pained by the loss of his son. Among the paper’s lines of argument are error-prone evocations of Jewishness, the meeting of Stephen and Bloom, and the strains of pro- and anti-Semitic thought in prominent Modernist writers. f the many critical clichés engendered by the readers and critics of O Joyce, the most useful, it seems to me, is Joseph Frank’s advisory that we cannot read Ulysses, but can only re-read it. This perception perfectly captured my own experience, first as an undergraduate reading what at the time seemed this most intimidating book; I later found it useful advice to share with my students, whom I wanted to be aware of Joyce’s challenge but free of intimidation; and now I find―in retirement from full-time teaching and thus free to work as I will―that it has become a useful sort of self- injunction. For I not only feel the continuing need to read Ulysses as I have for many years, opening it often at random, reminding myself of old textual pleasures and continuing to discover new ones; I also now find myself re- reading and re-thinking my own writing over the years on this greatest and most influential novel of the great Modernist age of the novel, hoping in the process to re-affirm and expand old insights and searching always for new ones. -

Madness As Redemption in “Circe”

Papers on Joyce 16 (2010): 123-137 Madness as Redemption in “Circe” EUNICE ROJAS Abstract The article explores the relationship between hallucination and forms of madness in the “Circe” episode of Ulysses. The author studies the function of madness in relation to the notions of guilt and sinfulness and as a means of atonement and salvation. Keywords: madness, guilt, sinfulness, atonement, salvation, “Circe.” In his schemata James Joyce identified the art of the “Circe” episode of Ulysses as “magic” and its technic as “hallucination.” Without a doubt, not only do both Bloom and Stephen spend the entire episode passing back and forth between dream-like visions and reality, but their hallucinations of each often fuse together, and the staged format of “Circe” allows even the objects of both protagonists‟ subconscious to be heard, either in onomatopoeic exclamations or in actual coherent speech. In fact, the hallucinatory nature of the episode even spreads at times to the stage directions, which in some cases clearly represent Bloom‟s consciousness rather than the third person narration typical of such directions. Joyce‟s use of hallucination in this episode is by no means arbitrary but instead the visions of Bloom and Stephen act as a form of madness. In choosing the technic of hallucination in this MADNESS AS REDEMPTION IN “CIRCE” episode Joyce is free to employ the many different uses of madness that have been made in literature to delve into the psyche of its characters. Most importantly, Joyce‟s use of madness is ultimately one of an attempted vehicle for redemption from sin.