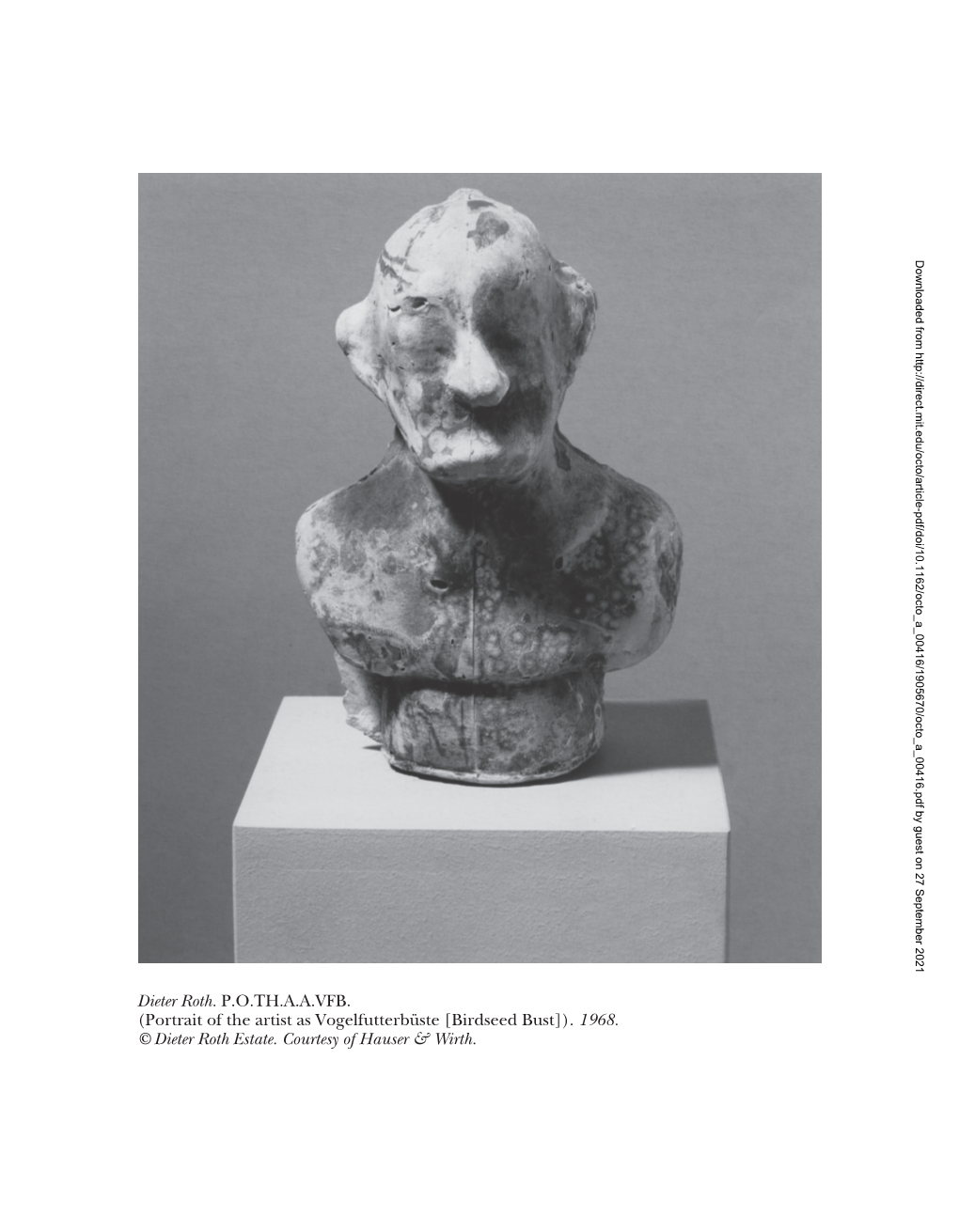

Dieter Roth. POTH.AAVFB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mews Dealers

Bernard Villersbq. Didier hb%ieu. For sukrscrlption (2 issues a >.ear) for French-English edition in November and May, 120 FF for Europe and 160 FF outside the MEWS European Union. Send to the above address in Saint- Urieix-la-Perche, France. Eric Gilt Conference $i Exhibitions, to be heEd in Sokember 2000, at the Gni\ersits of Notre Dame ~ith The Cotnambia College Chicago Ceates for Bwk & ,a conference on Eric Gill and the Guild of St. Pager Arts has moved to 1104 So. Wabash, Znd flr., Dominic. There uall also be: esltaibi~onsat the Sniae Chicago, EL 60605. Phone: (3 12)3446630, fax: L",.~seua?.,of Art and the Sfesbazrgh Libra3 Specid (3 i2(343-8082, e-snail: Coilections. Call for Papers due in Msch 2000, and BookdPir~er2~u~mail.coltlm.edu and website: ihe fo11ouing web site: Iktt~:/h~~w,coham.edu/cenPemh~ii I:t!p:i ?t\~$%i.,nd ed-LLJ-jsinem~anlgiiiJ Ann 3foore has been named director of the Center for Library and Archi~talExhibitierras are now on the Web Book Am in New Uork City. She formerly was at the at &ttg:lIwwu.siP.si.cduiSliLP~tbEicaQiunsi~n1inc- Alien Memorial Apt Museum Ga31ery of OberIin EsAibitions/onlia~c-exhibitions-titIeehtis the site %iiai"i Coiiege in Oberlin, Ohio. 3SO-c links, DEALERS Reparation da: Poesie Artist Book #I 1. Send 100 Paul-Uon Bisson-Millet has a new list, available Ifom originzl pages or multiple. a ~sualart. rnaiiB art. \ isud Saarserassc 62, D-=69 I5 f. Ncckargemund, Germany. poetq, postcards, computer art, cop) apt. -

PRESS RELEASE Art Into Life!

Contact: Anne Niermann / Sonja Hempel Press and Public Relations Heinrich-Böll-Platz 50667 Cologne Tel + 49 221 221 23491 [email protected] [email protected] PRESS RELEASE Art into Life! Collector Wolfgang Hahn and the 60s June 24 – September 24, 2017 Press conference: Thursday, June 22, 11 a.m., preview starts at 10 a.m. Opening: Friday, June 23, 7 p.m. In the 1960s, the Rhineland was already an important center for a revolutionary occurrence in art: a new generation of artists with international networks rebelled against traditional art. They used everyday life as their source of inspiration and everyday objects as their material. They went out into their urban surroundings, challenging the limits of the art disciplines and collaborating with musicians, writers, filmmakers, and dancers. In touch with the latest trends of this exciting period, the Cologne painting restorer Wolfgang Hahn (1924–1987) began acquiring this new art and created a multifaceted collection of works of Nouveau Réalisme, Fluxus, Happening, Pop Art, and Conceptual Art. Wolfgang Hahn was head of the conservation department at the Wallraf Richartz Museum and the Museum Ludwig. This perspective influenced his view of contemporary art. He realized that the new art from around 1960 was quintessentially processual and performative, and from the very beginning he visited the events of new music, Fluxus events, and Happenings. He initiated works such as Daniel Spoerri’s Hahns Abendmahl (Hahn’s Supper) of 1964, implemented Lawrence Weiner’s concept A SQUARE REMOVAL FROM A RUG IN USE of 1969 in his living room, and not only purchased concepts and scores from artists, but also video works and 16mm films. -

René Block Curating: Politics and Display René Block Interviewed by Sylvia Ruttimann and Karin Seinsoth

Interview with René Block Curating: politics and display René Block interviewed by Sylvia Ruttimann and Karin Seinsoth I. Gallery and Fair / Art and Capital Lueg and KH Hödicke had just left the academy; KP Brehmer and Sigmar Polke were still students, as Sylvia Ruttimann & Karin Seinsoth: In 1964, were Palermo, Knoebel and Ruthenbeck. All of them at the age of twenty-two, you founded your own started in the mid-sixties from point zero, like gallery in Berlin and went down in the history of the myself. We started together and we grew up together. art world for doing so. What inspired you to take that Wolf Vostell and, naturally, Joseph Beuys represented risk? the older generation, but hardly anyone was taking notice of their work back then. Th is made them René Block: Well, to begin with, it wasn’t a risk equal to the artists of the young generation from the at all but simply a necessity. From the time I was point of commerce. Even though artistically they seventeen, when I was a student at the Werkkunsts- have been more experienced. Th at was the “German chule (school of applied arts) Krefeld, I had the programme”. At the same time, I was also interested opportunity to experience close up how the museum in the boundary-transcending activities of the inter- director Paul Wember realized a unique avant-garde national Fluxus movement. Nam June Paik, George exhibition programme at the Museum Hans Lange, Brecht, Arthur Køpcke, Dick Higgins, Allison and also how he purchased works from those exhibi- Knowles, Emmet Williams, Dieter Roth, Robert tions for his museum. -

Selected Bibliography Cabanne, Pierre

selected bibliography Cabanne, Pierre. Dialogues with Marcel Gigerenzer, Gerd, et al. The Empire of Duchamp. Trans. Ron Padgett. New York: Chance: How Probability Changed Science Da Capo Press, 1987. and Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. Cage, John. Silence. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961. Hacking, Ian. The Taming of Chance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Caillois, Roger. Man, Play, and Games Press, 1990. (1958). Trans. Meyer Barash. New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1961. Hamilton, Ross. Accident: A Philosophical and Literary History. Chicago: University Caws, Mary Ann, ed. Surrealist Painters BOOKS Bourriaud, Nicolas, François Bon, and of Chicago Press, 2007. and Poets: An Anthology. Cambridge, MA: Kaira Marie Cabanas. Villeglé: Jacques Vil- Ades, Dawn, ed. The Dada Reader: A MIT Press, 2001. Henderson, Linda Dalrymple. Duchamp leglé. Paris: Flammarion, 2007. Critical Anthology. Chicago: University of in Context: Science and Technology in the Dalí, Salvador. Conquest of the Irrational. Chicago Press, 2006. Brecht, George. Chance-Imagery. New Large Glass and Related Works. Princeton, Trans. David Gascoyne. New York: Julien York: Great Bear Pamphlet / Something NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998. Andreotti, Libero, and Xavier Costa, Levy Gallery, 1935. Else Press, 1966. eds. Theory of the Dérive and other Situation- Hendricks, Jon. Fluxus Codex. Detroit: Diaz, Eva. “Chance and Design: Experi- ist Writings on the City. Barcelona: Museu Breton, André. Conversations: The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collec- mentation at Black Mountain College.” d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, 1996. Autobiography of Surrealism. Trans. Mark tion; New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988. PhD diss., Princeton University, 2008. Polizzotti. New York: Paragon House, Arp, Jean (Hans). -

Dorothy Iannone

Dorothy Iannone Air de Paris www.airdeparis.com [email protected] Dorothy Iannone, Berlin, 2009. © Jason Schmidt Air de Paris www.airdeparis.com [email protected] Dorothy Iannone was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1933. She attended Boston University and Brandeis University where she majored in Literature. In 1961 she successfully sued the U.S. Government on behalf of Henry Miller's "Tropic of Cancer", which until then was censured in the U.S., to allow its importation into the country. She begins painting in 1959 and travels extensively with her husband to Europe and the Far East. From 1963 until 1967, she runs a co-operative gallery on Tenth Street. New York together with her husband. In 1966 they live for some months in the South of France where she begins a close friendship with Robert Filliou and other artists from Fluxus. She meets and falls in love with German- Swiss artist Dieter Roth during a journey to Reykjavik and will share his life in different European cities until 1974. Two years later Iannone moves to Berlin after receiving a grant from the DAAD Berlin Artists' Program. She still lives and works in Berlin, where she pursues her artistic production. Since the beginning of her career in the 1960's, Dorothy Iannone has been making vibrant paintings, drawings, prints, films, objects and books, all with a markedly narrative and overtly autobiographical visual feel. Her oeuvre is likean exhilarating ode to an unbridled sexuality and celebration of ecstatic unity, unconditional love, and a singular attachment to Eros as a philosophical concept. -

Exhibition Checklist

Exhibition Checklist Dieter Roth Born 1930, Hannover, Germany. Died June 1998. Ohne Titel [roter Klee] (Untitled [Red clover]) 1944 Pencil and watercolor on paper 11 5/8 x 8 1/4" (29.5 x 21 cm) Kunstmuseum Bern, Toni Gerber Collection, Bern. Gift, 1983 Ohne Titel (farbiger Entwurf) (Untitled [Color design]) 1944 Pencil and watercolor on paper 8 3/16 x 5 13/16" (20.8 x 14.7 cm) Kunstmuseum Bern, Toni Gerber Collection, Bern. Gift, 1983 Selbstbildnis (Self-portrait) 1946 Enamel and charcoal on paper and frottage 9 9/16 x 9 13/16" (24.2 x 25 cm) Kunstmuseum Bern, Toni Gerber Collection, Bern. Gift, 1983 Aareufer in Solothurn (Bank of the Aare in Solothurn) 1947–48 Ink and oil on pressboard panel 13 x 18 7/8" (33 x 48 cm) Dieter Roth Foundation, Hamburg Pimpfe mit Fahne (Cubs with flag) 1947 Linocut 7 15/16 x 6 5/8" (20.2 x 16.8 cm) Kunstmuseum Bern, Toni Gerber Collection, Bern. Gift, 1983 In Bellach 1948 Watercolor on paper 6 5/16 x 9 13/16" (16 x 25 cm) (irreg.) Dieter Roth Foundation, Hamburg Stilleben (Still Life) 1948 Gouache on pressboard panel 5 3/4 x 7 5/16" (14.5 x 18.5 cm) Dieter Roth Foundation, Hamburg Druckstock (Electrotype) 1949 Chip carving in tea-box plywood 17 1/8 x 17 1/8" (43.5 x 43.5 cm) Dieter Roth Foundation, Hamburg Katze (Cat) 1950 Distemper on canvas 24 x 15 9/16" (61 x 39.5 cm) Dieter Roth Foundation, Hamburg Musikplakat (Music poster) c. -

Multiples in Late Modern Sculpture: Influences Within and Beyond

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Faculty Publications School of Design 6-2015 Multiples in Late Modern Sculpture: Influences Within and Beyond Daniel Spoerri’s 1959 Edition MAT Leda Cempellin South Dakota State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/design_pubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Cempellin, Leda. “Multiples in Late Modernism: Influences Within and Beyond Daniel Spoerri’s 1959 Edition MAT.” Nierika: Revista de Estudios de Arte (Ibero Publicaciones), vol. 7, special issue Las piezas múltiples en la escultura (June 2015): 58-73. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Design at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 58 Multiples in Late Modern nierikaARTÍCULOS ATEMÁTICOSRTÍCULOS TEMÁTICOS Sculpture: Influences Within and Beyond Daniel Spoerri’s 1959 Edition MAT 1 1 Acknowledgments: Daniel Spoerri and Leda Cempellin Barbara Räderscheidt; South Dakota State University Corinne Beutler and the [email protected] Daniel Spoerri Archives at the Swiss National Library; Hilton M. Briggs Library, South Dakota State University; Adamo Cempellin, Severina Armida Sparavier, Mary Harden, Danilo Restiotto. Fig. 1: Daniel Spoerri, Claus and Nusch Bremer reading concrete poems at the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf, 1959. Cour- tesy Daniel Spoerri. Abstract The firstEdition MAT was founded by Daniel Spoerri in 1959 and recreated in collaboration with Karl Gerstner in 1964 and 1965, with a special Edition MAT Mot the same year. -

INTERSECTIONS, BOUNDARIES and PASSAGES: TRANSGRESSING the CODEX October 2011 Intersections, Boundaries and Passages: Transgressing the Codex

Keith Dietrich INTERSECTIONS, BOUNDARIES AND PASSAGES: TRANSGRESSING THE CODEX October 2011 Intersections, Boundaries and Passages: Transgressing the Codex Inaugural lecture presented on 4 October 2011 Prof. K.H. Dietrich Department of Visual Arts Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Editor: SU Language Centre Design: Keith Dietrich Printing: Sunprint ISBN: 978-0-7972-1335-7 Keith Dietrich was born in Johannesburg in 1950 and studied graphic design at Stellenbosch University, where he graduated with a BA degree in Visual Arts in 1974. Between 1975 and 1977 he studied painting at the National Higher Institute for Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. He obtained his MA in Fine Arts (cum laude) in 1983 and his D Litt et Phil in Art History in 1993, both at the University of South Africa (Unisa). He has lectured at the University of Pretoria and Unisa, and is currently Chair INTRODUCTION of the Department of Visual Arts at Stellenbosch University. He has participated in over thirty community interaction projects in southern Africa and has received a number of awards, in South Africa and abroad, for both his creative and his academic work. He has participated in group exhibitions and biennials in Belgium, Botswana, Chile, Egypt, Germany, Italy, Namibia, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the USA, and has held 20 solo exhibi- tions in South Africa. His work is represented in 34 corporate and public collections in South Africa and abroad. Given that the convention of an inaugural lecture Artists’ books lie at the intersection of disciplines in excludes art practice, I decided to present an inaugural ex- both the visual arts and literature, and include poetry, prose, hibition. -

Dieter Roth “Drawings” April 5 - May 3, 2008

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Dieter Roth “Drawings” April 5 - May 3, 2008 Gladstone Gallery is pleased to announce an exhibition of over 500 drawings by German- born Swiss artist Dieter Roth. Covering a vast terrain throughout his career, producing prints, sculpture, installation, audio and video, Roth thoroughly documented his subjective view of the world while eluding any easy classification. The thirty-six bundled groups of drawings on view were created between 1977 and 1990 and represent a central part of his oeuvre, despite their rare showings during his life. While appearing in the Kopiebucher (Copy Books) that he created in small editions during his life, this exhibition marks the US debut of some of these most telling and essential works from this fascinating artist. Roth collected and bound these works on paper in unique books that he mostly kept private during his life, turning them into a wondrous archive of the artist’s mind. Just as he exhibited the dexterity of his skill in creating objects from such disparate materials, such as chocolate and sausage, his drafting techniques range from simple graphite lines to more swirling compositions rendered from multiple layers of ink and gouache over-painting. Working in series allowed Roth to sustain his flowing train of thought, while permitting his constant experimentation with texture and imagery. Though some works may seem unfinished, failed, or hastily dashed-off, in each work his gestural fluidity spirals closer to a portrait of the mind in constant production. The diary would be an apt metaphor for the position these played in his conceptual view of the world, as the continued insistence upon his working mind as subject shades each group of drawings with the impressions and feelings that filled his day- to-day life. -

Art, Food, and the Social and Meliorist Goals of Somaesthetics

Page 85-101 Art, Food, and the Social and Meliorist Goals of Somaesthetics Art, Food, and the Social and Meliorist Goals of Somaesthetics Else Marie Bukdahl Abstract: In his somaesthetics, Richard Shusterman emphasizes, to a much greater degree than other contemporary pragmatists, the importance of corporality for all aspects of human existence. He focuses particularly on “the critical study and cultivation of how the living body (or soma) is used as the site of sensory appreciation (aesthesis) and creative self-stylization.”1 Somaesthetics is grounded as an interdisciplinary project of theory and practice. Many in the academic field have asked Richard Shusterman why he has not included “the art of eating” in his somaesthetics. He recently decided to do this and he has held lectures on this subject in Italy with the title The Art of Eating. L’Art di mangiare at the conference Food, Philosophy and Art - CIBO, Filosofia e Arte, Convergence Pollenzo, April 4-5, 2013 in collaboration with students from the University of Gastronomic Sciences. He has opened a new field, which is discussed in this article. The main subject of this article on visual art and eating will be a presentation of the internationally renowned Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija, who has created many surprising installations in Thailand, other countries in the east, Europe and particularly the US, where he resides and is professor at Columbia University. His installations often take the form of stages or rooms for sharing meals, cooking, reading and playing music. The architecture or other structures he uses always form the framework for different social events. -

Intense Singularities: Dieter Roth's and Henning Christiansen's

INTENSE SINGULARITIES: DIETER ROTH’S AND HENNING CHRISTIANSEN’S PROCESSUAL AESTHETICS LESLIE SCHUMACHER A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO December 2017 © Leslie Schumacher, 2017 Abstract This thesis examines the potential flux and indeterminacy within an aesthetic experience, with a particular focus on the works of Dieter Roth and Henning Christiansen. This study looks at the desires, forces, and energies that are at work in the aesthetic experience, and further, aims to evoke the nature of the intensities that are generated through each interaction. Informed by Jean- Francois Lyotard and Julia Kristeva, this research shifts the perspective from a fixed systematic approach that is concerned with the works objective qualities, inherent essence, or material properties, to a processual approach that works through the nuances, ambiguities, and energies that constitute arts vitality. Applying Lyotard’s libidinal aesthetics to works of art whose materiality is transitory adds further complexity to an understanding of the energies and forces that are at work in an aesthetic experience, initiating a theory of perpetual flux, fragmentation, and singular intensities. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract........................................................................................................................ii Table of Contents.........................................................................................................iii -

Dieter Roth Shit Sublime

Diter Rot Dieter Rot Dieter Roth Dieterich Roth Karl-Dietrich Roth Shit Sublime For the exhibition, a richly illustrated catalogue will be issued containing the complete list of Dieter Roth’s works in the Museum Ostwall Collection and of the works on Dieter Roth permanent loan from the Spankus Dieter Roth Collection. Shit Sublime 21 May - 28 August 2016 www.facebook.com/museum.ostwall www.instagram.com/museumostwall www.twitter.com/MuseumOstwall #schönescheisse_mo #museumostwall The Museum Ostwall in the Dortmund U Tower Leonie-Reygers-Terrasse 44137 Dortmund Germany + 49 (0)231 5024723 An exhibition by the Museum Ostwall in the Dortmund [email protected] U Tower including works of the Museum Ostwall Collection www.museumostwall.dortmund.de and Spankus Dieter Roth Collection Groundplan skylight hall Collaborations Poetry as truth? The indeterminate self Records of everyday life View of the World “Automatic beauty” with holes and lines Introduction To some, the title chosen for the exhibition may seem e.g. graphic prints, music, mould pictures, video art and blatantly provocative. In fact, however, it is intended even poetry. With self-irony he restrains his envy of fel- literally. Firstly, Dieter Roth often resorted to the low artists, girding himself against criticism at the same imagery of digestion to describe his work and, secondly, time. He publishes a series of volumes of poetry entitled his entire output as an artist was pervaded by a desire “shit books” because “I wanted to be able to offer shit- to unite the supposed opposites of beauty and waste, of tiness with impunity […].” Roth, a jack-of-all-trades and dilettantism and artistic mastery.