Use of Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 2021Course Guide Course Guide Exmouth

2021 2021COURSE GUIDE COURSE GUIDE EXMOUTH CARNARVON GERALDTON BATAVIA COAST MARITIME INSTITUTE Contents TECHNOLOGY PARK IT ALL STARTS HERE 2 MOORA At Central Regional TAFE we’ll help you find your career, find your calling, find your start. KALGOORLIE MERREDIN LET’S GET THE FACTS 4 NORTHAM Why choose Vocational Education & Training? LEARN BY DOING 5 Simulated workplace learning HELPING YOU SUCCEED 6 Contact us Student Services 1800 672 700 JOBS & SKILLS CENTRES 7 [email protected] We can make it easier! centralregionaltafe.wa.edu.au WHERE ARE YOU HEADING? 8 VETDSS, PAIS, Pre-Apprenticeship, Apprenticeship/ Traineeship, University Pathways, Qualifications Batavia Coast Kalgoorlie Maritime Institute 34 Cheetham St 133 Separation Point Cl Kalgoorlie WA 6430 GET STRAIGHT INTO IT 10 Geraldton WA 6530 Pre-apprenticeships, Apprenticeships & Traineeships Merredin Carnarvon 42 Throssell Rd FOR ALL YOUR TRAINING NEEDS 11 14 Camel Ln Merredin WA 6415 Workforce solutions Carnarvon WA 6701 Moora Exmouth 242 Berkshire Valley Rd MAKING TRAINING AFFORDABLE 12 Ningaloo Centre Moora WA 6510 Don’t put your future on hold Cnr Murat Rd & Truscott Cres Northam Exmouth WA 6707 GET SKILLS READY 13 LOT 1 Hutt St There’s never been a better time to get into training Geraldton Northam WA 6401 173 – 175 Fitzgerald St Technology Park Geraldton WA 6530 STUDY OPTIONS FOR ALL 14 Cnr Deepdale Rd & What study mode suits you? Arthur Rd Geraldton WA 6532 THE NEXT STEP 15 How to enrol CRTAFE acknowledges the Aboriginal peoples of the Midwest, Gascoyne, Wheatbelt and Goldfields regions as traditional custodians COURSE INDEX 67 of the lands and waters. -

Australian Exchange (Kalgoorlie) 2017

Australian Exchange (Kalgoorlie) 2017 Erena Hosford—RMIP Wairarapa We are all visitors to this time, this place. We are just passing through. Our purpose here is to observe, to learn, to grow, to love… and then we return home. – Australian Aboriginal Proverb The super pit In July 2017 I was lucky enough to be given the opportunity to be placed in rural Western Australia for two weeks of my 5th year medical training. I was placed at Kalgoorlie Hospital in the city of Kalgoorlie-Boulder, which is in the goldfields 595km inland from Perth. The town has a population of over 32,000 people and was founded in 1893 during the gold rush. The largest employer in the area is the ‘Super pit’, an open cut gold mine, which is over 3 km long. The evening my fellow RMIP classmate and I landed in Kalgoorlie we were greeted at the airport by staff from the medical school who took us to our accommodation. There we met some of the Australian rural medical students. They had just started their mid year break but were still happy to take us out for dinner and show us around the town. The next day we started at the hospital. Kalgoorlie Hospital has an incredibly large catchment area, with some patients having travelled over 900km to attend clinics. While in Kalgoorlie I was on the Paediatric and General Medicine teams. I found the medicine there to be really interesting. There were many indigenous Australian patients, as well as a surprisingly large amount of New Zealanders (who move to Kalgoorlie to work in the mines). -

A Guide to Main Roads Rest Areas and Roadside Amenities

! Animal Alert Many of the major rural highways areunfenced due to the vast expanse of land, thereforeno barriers are A Guide to present to prevent wild or Main Roads rest areas pastoral animals wandering and roadside amenities across the road. ON MAJOR ROUTES IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA Be alert for animals on the road, particularly dusk and dawn. Watch out for warning signs on the road, different regions have different animals. Slow down and sound your horn if you encounter an animal. MWain Roads estern Australia Don Aitken Centre ,, Waterloo Crescent East Perth WA 6004 Phone138 138 | www.mainroads.wa.gov.au Please be aware that while every effort is made to ensure the currency of the information, data can be altered subsequent to original distribution and can also become quickly out- of-date. Information provided on this publication is also available on the Main Roads website. Please subscribe to the Rest Areas page for any updates. MARCH 2015 Fatigue is a silent killer on Western Australian roads. Planning ahead is crucial to managing fatigue on long A roadside stopping place is an area beside the road road trips. designed to provide a safe place for emergency stopping or special stopping (e.g. rest areas, scenic lookouts, Distances between remote towns can information bays , road train assembly areas). Entry signs indicate what type of roadside stopping place it is. Facilities be vast and in some cases conditions within each vary. can be very hot and dry with limited fuel, water and food available. 24 P Rest area 24 hour Information Parking We want you to enjoy your journey rest area but more importantly we want you to stay safe. -

Submission of Form BA20 Notice of Consent to the Department of Housing

Submission of Form BA20 Notice of Consent to the Department of Housing The following contact details should be used in relation to obtaining written consent from the Department of Housing as the adjoining property owner along a shared property boundary. 1. Where the Department of Housing property is occupied or construction has been completed the attached list of suburbs should be used to identify the Regional Office responsible for that suburb. The Notice of Consent Form BA20 and relevant documentation should be submitted to the Regional Manager using the details provided for that particular office. 2. Where construction has not yet commenced on the Department of Housing property or where construction is still in progress then the Notice of Consent Form BA20 and relevant documentation should be submitted to the Manager Professional Services using the details provided. NOTE – Approval will be delayed if the Notice of Consent Form BA20 and relevant documentation is not submitted to the correct processing area. -

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’S Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’S

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’s Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’s Western Australia PART 1. GWW NORTHERN Southern Cross Kalgoorlie Widgiemooltha birds are in our nature ® Australia AUSTRALIA Introduction The birds and places of the north-west region of the Great Western Woodlands are presented in this booklet. This area includes tall woodlands on red soils, shrublands on yellow sand plains and mallee on sand and loam soils. Landforms include large granite outcrops, Banded Ironstone Formation (BIF) Ranges, extensive natural salt lakes and a few freshwater lakes. The Great Western Woodlands At 16 million hectares, the Great Western Woodlands (GWW) is close to three quarters the size of Victoria and is the largest remaining intact area of temperate woodland in the world. It is located between the Western Australian Wheatbelt and the Nullarbor Plain. BirdLife Australia and The Nature Conservancy joined forces in 2012 to establish a long-term project to study the birds of this unique region and to determine how we can best conserve the woodland birds that occur here. Kalgoorlie 1 Groups of volunteers carry out bird surveys each year in spring and autumn to find out the species present, their abundance and to observe their behaviour. If you would like to know more visit http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/great-western-woodlands If you would like to participate as a volunteer contact [email protected]. All levels of experience are welcome. The following six pages present 48 bird species that typically occur in four different habitats of the north-west region of the GWW, although they are not restricted to these. -

Roads 2030 Strategies for Significant Local Government Roads – Goldfields Esperance Region P a G E

Roads 2030 Strategies for Significant Local Government Roads – Goldfields Esperance Region Page | i CONTENTS ROADS2030REGIONALSTRATEGIESFORSIGNIFICANTLOCALROADS GOLDFIELDSESPERANCEREGION INTRODUCTION REGIONAL MAP ROAD/ROUTES PAGE ALBIONDOWNS–YEELIRRIEROAD………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 BANDYA–BANJAWARNROUTE……………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 BARWIDGEE–YANDALROUTE…………………………………………………………………………………………. 7 BLACKSTONE–WARBURTONROAD………………………………………………………………………………… 8 BROADARROW–CARBINEROUTE………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 BULONGROAD…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….. 10 BURRAROCKROAD…………………………………………………………………………………………………….……. 11 CAPELEGRANDROAD………………………………………………………………………………………………….….. 12 CARINSROAD…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….. 13 CASCADESROAD…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 14 CAVEHILLROAD………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 15 COOLGARDIE–MENZIESROUTE………………………………………………………………………………….…… 16 COOLINUPROAD……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….. 17 DARLOTROAD………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………. 18 DAYLUPROAD……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………. 19 DURKINROAD………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 20 ELEVENMILEBEACHROAD………………………………………………………………………………………………. 21 ELORA–MTWELDROAD…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 22 ERLISTOUNROAD…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 23 ESPERANCETOWNROADS………………………………………………………………………………………………. 24 FISHERIESROAD………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 25 GILES–MULGAPARKROAD………………………………………………………………………………………….... 26 GLENORN–YUNDAMINDRA……………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Regions and Local Government Areas Western Australia

IRWIN THREE 115°E 120°E 125°E SPRINGS PERENJORI YALGOO CARNAMAH MENZIES COOROW Kimberley DALWALLINU MOUNT MARSHALL REGIONS AND LOCAL Pilbara MOORA DANDARAGAN Gascoyne KOORDA MUKINBUDIN GOVERNMENT AREAS WONGAN-BALLIDU Midwest DOWERIN WESTONIA YILGARN Goldfields-Esperance VICTORIA PLAINS TRAYNING GOOMALLING NUNGARIN WESTERN AUSTRALIA - 2011 Wheatbelt GINGIN Perth WYALKATCHEM Peel CHITTERING South West Great KELLERBERRIN Southern TOODYAY CUNDERDIN MERREDIN NORTHAM TAMMIN YORK TIMOR QUAIRADING BRUCE ROCK NAREMBEEN 0 50 100 200 300 400 SEA BEVERLEY SERPENTINE- Kilometres BROOKTON JARRAHDALE CORRIGIN KONDININ 15°S MANDURAH WANDERING PINGELLY 15°S MURRAY CUBALLING KULIN WICKEPIN WAROONA BODDINGTON Wyndham NARROGIN WYNDHAM-EAST KIMBERLEY LAKE GRACE HARVEY WILLIAMS DUMBLEYUNG KUNUNURRA COLLIE WAGIN BUNBURY DARDANUP WEST ARTHUR CAPEL RAVENSTHORPE WOODANILLING KENT DONNYBROOK- KATANNING BUSSELTON BALINGUP BOYUP BROOK BROOMEHILL- AUGUSTA- KOJONUP JERRAMUNGUP MARGARET BRIDGETOWN- TAMBELLUP RIVER GREENBUSHES GNOWANGERUP NANNUP CRANBROOK Derby MANJIMUP DERBY-WEST KIMBERLEY PLANTAGENET BROOME KIMBERLEY ALBANY DENMARK Fitzroy Crossing Halls Creek INSET BROOME INDIAN OCEAN HALLS CREEK 20°S 20°S PORT HEDLAND Wickham Y Dampier PORT HEDLAND KARRATHA Roebourne R ROEBOURNE O T I R Onslow EAST PILBARA Pannawonica PILBARA R Exmouth E T ASHBURTON N EXMOUTH Tom Price R E H Paraburdoo Newman T R O N CARNARVON GASCOYNE UPPER GASCOYNE CARNARVON 25°S 25°S MEEKATHARRA NGAANYATJARRAKU WILUNA Denham MID WEST SHARK BAY MURCHISON Meekatharra A I L CUE A R NORTHAMPTON T Kalbarri -

EAST YILGARN GEOSCIENCE DATABASE, 1:100 000 GEOLOGY of the LEONORA– LAVERTON REGION, EASTERN GOLDFIELDS GRANITE–GREENSTONE TERRANE — an EXPLANATORY NOTE by M

REPORT EAST YILGARN GEOSCIENCE DATABASE 84 1:100 000 GEOLOGY OF THE LEONORA–LAVERTON REGION EASTERN GOLDFIELDS GRANITE–GREENSTONE TERRANE — AN EXPLANATORY NOTE by M. G. M. Painter, P. B. Groenewald, and M. McCabe GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA REPORT 84 EAST YILGARN GEOSCIENCE DATABASE, 1:100 000 GEOLOGY OF THE LEONORA– LAVERTON REGION, EASTERN GOLDFIELDS GRANITE–GREENSTONE TERRANE — AN EXPLANATORY NOTE by M. G. M. Painter, P. B. Groenewald, and M. McCabe Perth 2003 MINISTER FOR STATE DEVELOPMENT Hon. Clive Brown MLA DIRECTOR GENERAL, DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRY AND RESOURCES Jim Limerick DIRECTOR, GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Tim Griffin REFERENCE The recommended reference for this publication is: PAINTER, M. G. M., GROENEWALD, P. B., and McCABE, M., 2003, East Yilgarn Geoscience Database, 1:100 000 geology of the Leonora–Laverton region, Eastern Goldfields Granite–Greenstone Terrane — an explanatory note: Western Australia Geological Survey, Report 84, 45p. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-publication entry Painter, M. G. M. East Yilgarn Geoscience Database, 1:100 000 geology of the Leonora–Laverton region, Eastern Goldfields Granite–Greenstone Terrane — an explanatory note Bibliography. ISBN 0 7307 5739 0 1. Geology — Western Australia — Eastern Goldfields — Databases. 2. Geological mapping — Western Australia — Eastern Goldfields — Databases. I. Groenewald, P. B. II. McCabe, M., 1965–. III. Geological Survey of Western Australia. IV. Title. (Series: Report (Geological Survey of Western Australia); 84). 559.416 ISSN 0508–4741 Grid references in this publication refer to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 1994 (GDA94). Locations mentioned in the text are referenced using Map Grid Australia (MGA) coordinates, Zone 51. All locations are quoted to at least the nearest 100 m. -

What Questions Does the History of a Tri-Border School Raise?

Submission – Education in Rural and Complex Environments What questions does the history of a tri-border school raise? Max Angus 4 March 2020 Introduction This submission presents a brief history of a particular school located in the tri-border region of Central Australia. The account is confined to the years 1934 – 1990 and addresses most of the Committee’s terms of refence. It is drawn from a larger work in progress. The submission does not document the school’s more recent history; however, the argument can be made that the die was cast during the earlier years, and what happened during those years is an important factor shaping how schooling is provided today. In addition, arising from the history I make a number of observations about issues that are germane to the Committee’s term of reference. The views expressed are my own. The particular school to which most of the remarks refer Is today known as the Ngaanyatjarra Lands School, a composite of eight campuses, though until 1978 there was only a single institution - Warburton Range Primary School. Obviously, any generalisations to other schools should made with caution. The sub-category of schools to which generalisations about Warburton best fit are those with the following characteristics: • They are located within an Aboriginal-governed community in the tri-border region; • The vernacular speech is a Western Desert dialect; • There is no local industry in or near the community offering employment opportunities; • Entry to the community has always required a permit, isolating it from European society; and • There continues to be a strong attachment to the Tjukurrpa and the Law; this attachment overrides the usual civic obligations that apply in predominantly European settlements. -

Goldfields-Esperance Recovery Plan

Goldfields-Esperance Recovery Plan The Goldfields-Esperance Recovery Plan is part of the next step in our COVID-19 journey. It’s part of WA’s $5.5 billion overarching State plan, focused on building infrastructure, economic, health and social outcomes. The Goldfields-Esperance Recovery Plan will deliver a pipeline of jobs in sectors including construction, manufacturing, tourism and hospitality, renewable energy, education and training, agriculture, conservation and mining. WA’s recovery is a joint effort, it’s about Government working with industry together. We managed the pandemic together as a community. Together, we will recover. Investing in our Schools and Rebuilding our TAFE Sector • $500,000 to Kalgoorlie-Boulder Community High School for a refurbishment of the Performing Arts area • $10 million to Central Regional TAFE’s Kalgoorlie campus for a new Heavy Plant and Engineering Trades Workshop, to expand training for mechanic and engineering trades, tailored to support resource sector needs • $25 million for free TAFE short courses to upskill thousands of West Australians, with a variety of free courses available at Central Regional TAFE’s Kalgoorlie campus • $32 million to expand the Lower Fees, Local Skills program and significantly reduce TAFE fees across 39 high priority courses • $4.8 million for the Apprenticeship and Traineeship Re-engagement Incentive that provides employers with a one-off payment of $6,000 for hiring an apprentice and $3,000 for hiring a trainee, whose training contract was terminated on, or after, March -

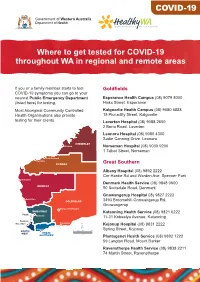

Where to Get Tested for COVID-19 in Regional and Remote WA

COVID-19 Where to get tested for COVID-19 throughout WA in regional and remote areas If you or a family member starts to feel Goldfields COVID-19 symptoms you can go to your nearest Public Emergency Department Esperance Health Campus (08) 9079 8000 (listed here) for testing. Hicks Street, Esperance Most Aboriginal Community Controlled Kalgoorlie Health Campus (08) 9080 5888 Health Organisations also provide 15 Piccadilly Street, Kalgoorlie testing for their clients. Laverton Hospital (08) 9088 2600 2 Beria Road, Laverton Leonora Hospital (08) 9080 4300 Sadie Canning Drive, Leonora KIMBERLEY Broome Norseman Hospital (08) 9039 9200 1 Talbot Street, Norseman Port Hedland Karratha PILBARA Great Southern Albany Hospital (08) 9892 2222 Cnr Hardie Rd and Warden Ave, Spencer Park Carnarvon Denmark Health Service (08) 9848 0600 MIDWEST 50 Scotsdale Road, Denmark Gnowangerup Hospital 08) 9827 2222 Geraldton GOLDFIELDS 3493 Broomehill-Gnowangerup Rd, Gnowangerup Kalgoorlie-Boulder WHEATBELT Katanning Health Service (08) 9821 6222 Perth Northam 11-31 Kobeelya Avenue, Katanning Bunbury Busselton Esperance Kojonup Hospital (08) 9831 2222 Albany Spring Street, Kojonup SOUTH 0 100 200 400 WEST GREAT km SOUTHERN Plantagenet Health Service (08) 9892 1222 59 Langton Road, Mount Barker Ravensthorpe Health Service (08) 9838 2211 74 Martin Street, Ravensthorpe Kimberley Pilbara Broome Health Campus (08) 9194 2222 Hedland Health Campus (08) 9174 1000 26 Robinson Street, Broome 26-34 Calebatch Way, South Hedland Derby Hospital (08) 9193 3333 Karratha Health -

Major Resource Projects, Western Australia

112° 114° 116° 118° 120° 122° 124° 126° 128° 10° 10° JOINT PETROLEUM MAJOR RESOURCE PROJECTS DEVELOPMENT AREA Western Australia — 2021 Principal resource projects operating with sales >$5 million in 2019–20 are in blue text NORTHERN TERRITORY WESTERN AUSTRALIA Resource projects currently under construction are in green text m 3000 Planned mining and petroleum projects with at least a pre-feasibility study (or equivalent) completed are in red text Principal resource projects recently placed on care and maintenance, or shut are in purple text Ashmore Reef West I East I 12° 114° 116° Middle I 2000 m 2000 TERRITORY OF ASHMORE 12° INSET A AND CARTIER ISLANDS T I M O R S E A SCALE 1:1 200 000 50 km Hermes Lambert Athena m 1000 Angel Searipple Persephone Cossack INDONESIA Perseus Wanaea AUSTRALIA North Rankin SHELF COMMONWEALTH 'ADJACENT AREAS' BOUNDARY Chandon Goodwyn Holothuria Reef Keast Trochus I Sculptor Tidepole Dockrell Pyxis Lady Nora Pemberton Prelude Troughton I Cape Londonderry SIR GRAHAM Cape Wheatstone Talbot Ichthys Parry HarbourTroughton Passage MOORE IS Lesueur I Jansz–Io Eclipse Is Pluto Cassini I Cape Rulhieres WEST Mary I Iago Torosa NAPIER 20° Browse I Oyster Rock Passage Vansittart Xena BROOME Blacktip Bay Scott Reef Fenelon I BAY 200 m 200 Yankawinga I Reindeer Kingsmill Is 14° Cone Mountain RIVER JOSEPH BONAPARTE 14° Brunello Brecknock Maret Is Prudhoe Is MONTAGUE ADMIRALTY GULF 20° Chrysaor/Dionysus Turbin I SOUND GULF Reveley I Calliance Warrender Hill RIVER Carson River Buckle Head Wandoo GEORGE BIGGE I Mt Connor Mt