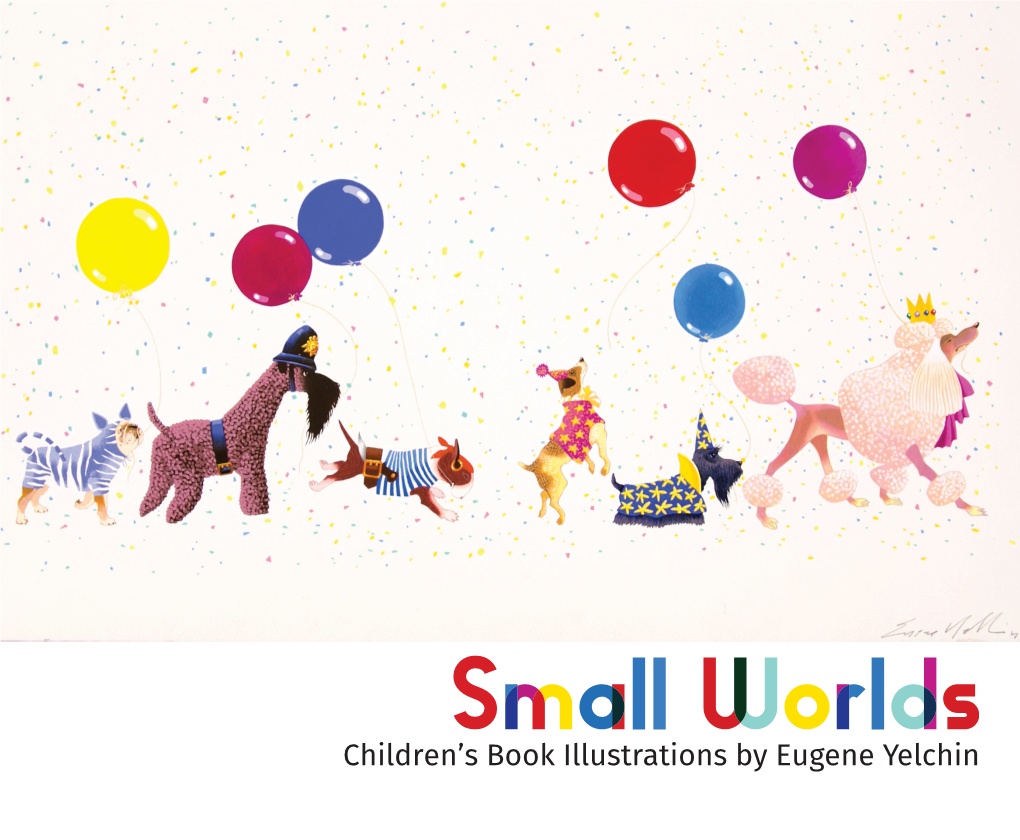

Children's Book Illustrations by Eugene Yelchin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Different Drummers

Special Issue: Different Drummers March/April 2013 Volume LXXXIX Number 2 ® Features Barbara Bader 21 Z Is for Elastic: The Amazing Stretch of Paul Zelinsky A look at the versatile artist’s career. Roger Sutton 30 Jack (and Jill) Be Nimble: An Interview with Mary Cash and Jason Low Independent publishers stay flexible and look to the future. Eugene Yelchin 41 The Price of Truth Reading books in a police state. Elizabeth Burns 47 Reading: It’s More Than Meets the Eye Making books accessible to print-disabled children. Columns Editorial Roger Sutton 7 See, It’s Not Just Me In which we celebrate the nonconforming among us. The Writer’s Page Polly Horvath and Jack Gantos 11 Two Writers Look at Weird Are they weird? What is weird, anyway? And will Jack ever reply to Polly? Different Drums What’s the strangest children’s book you’ve ever enjoyed? Elizabeth Bird 18 Seven Little Ones Instead Luann Toth 20 Word Girl Deborah Stevenson 29 Horrible and Beautiful Kristin Cashore 39 Embracing the Strange Susan Marston 46 New and Strange, Once Elizabeth Law 58 How Can a Fire Be Naughty? Christine Taylor-Butler 71 Something Wicked Mitali Perkins 72 Border Crossing Vaunda Micheaux Nelson 79 Wiggiling Sight Reading Leonard S. Marcus 54 Wit’s End: The Art of Tomi Ungerer A “willfully perverse and subversive individualist.” (continued on next page) March/April 2013 ® Columns (continued) Field Notes Elizabeth Bluemle 59 When Pigs Fly: The Improbable Dream of Bookselling in a Digital Age How one indie children’s bookstore stays SWIM HIGH ACROSS T H E SKY afloat. -

Play, Literacy, and Youth

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 10 Number 1 Spring 2012 ISSN 1542-9806 The PLAY issue: Play, Literacy, and Youth Sendak, Riordan, Joyce: Read More About ’Em! Making Mentoring Work PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT Table Contents● ofVolume 10, Number 1 Spring 2012 Notes 25 Instruction, a First Aid Kit, and Communication 2 Editor’s Note Necessary Components in the Sharon Verbeten Mentoring Relationship Meg Smith Features 27 Beyond Library Walls Improving Kindergarten Readiness SPECIAL FOCUS: in At-Risk Communities Play and Literacy Kim Snell 3 We Play Here! Bringing the Power of Play 30 Newbies and Newberys into Children’s Libraries Reflections from First-Time Betsy Diamant-Cohen, Tess Prendergast, Christy Estrovitz, Newbery Honor Authors Carrie Banks, and Kim van der Veen Sandra Imdieke 11 The Preschool Literacy And You 37 Inside Over There! (PLAY) Room Sendak Soars in Skokie Creating an Early Literacy Play Area in Your Library 38 An Exploratory Study of Constance Dickerson Children’s Views of Censorship Natasha Isajlovic-Terry and Lynne (E.F.) McKechnie 16 A Museum in a Library? Science, Literacy Blossom at 44 The Power of Story Children’s Library Discovery Center The Role of Bibliotherapy for the Library Sharon Cox James -

Newbery Medal and Honor Books, 2012-2018

Newbery Medal and Honor Books, 2012-2018 2018 Medal Winner: Hello, Universe by Erin Entrada Kelly (Greenwillow/HarperCollins) Honor Books: ● Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut, written by Derrick Barnes, illustrated by Gordon C. James (Bolden/Agate) ● Long Way Down, by Jason Reynolds (Atheneum/Simon & Schuster Children’s) ● Piecing Me Together, by Renée Watson (Bloomsbury) 2017 Medal Winner: The Girl Who Drank the Moon by Kelly Barnhill (Algonquin Young Readers/Workman) Honor Books: ● Freedom Over Me: Eleven Slaves, Their Lives and Dreams Brought to Life by Ashley Bryan, written and illustrated by Ashley Bryan (Atheneum/Simon & Schuster) ● The Inquisitor’s Tale: Or, The Three Magical Children and Their Holy Dog, written by Adam Gidwitz, illustrated by Hatem Aly (Dutton/Penguin Random House) ● Wolf Hollow, by Lauren Wolk (Dutton/Penguin Random House) 2016 Medal Winner: Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña (G.P. Putnam's Sons/Penguin) Honor Books: ● The War that Saved My Life by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley (Dial Books for Young Readers/Penguin) ● Roller Girl by Victoria Jamieson (Dial Books for Young Readers/Penguin) ● Echo by Pam Muñoz Ryan (Scholastic Press/Scholastic Inc.) 2015 Medal Winner: The Crossover by Kwame Alexander (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) Honor Books: ● El Deafo by Cece Bell (Amulet Books, an imprint of ABRAMS) ● Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson (Nancy Paulsen Books, an imprint of Penguin Group LLC) 2014 Medal Winner: Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures by Kate DiCamillo (Candlewick Press) Honor Books: ● Doll Bones by Holly Black (Margaret K. McElderry Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing) ● The Year of Billy Miller by Kevin Henkes (Greenwillow Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) ● One Came Home by Amy Timberlake (Alfred A. -

Newbery Award Committee, the Caldecott Award Committee, the Sibert Award Committee, the Wilder Award Committee, and the Notable Children’S Books Committee

RANDOLPH CALDECOTT MEDAL COMMITTEE MANUAL June 2009 Randolph Caldecott Medal Committee Manual – Formatted August 2015 1 FOREWORD Randolph Caldecott The Caldecott Medal is named for Randolph Caldecott (1846-1886), a British illustrator best known for his nursery storybooks, including The Babes in the Wood, The Hey Diddle Diddle Picture Book, Sing a Song of Sixpence. Many of the scenes illustrated in these works depict the English Countryside and the people who lived there. Although Caldecott began sketching as a child, his parents saw no future for him in art and sent him to work at a bank in the city. He still found time to sketch, though, and in addition to the farmlands of his youth, Caldecott began to draw urban scenes and people, including caricatures of some bank customers. When his drawings were accepted for publication in the Illustrated London News and other papers, Caldecott quit his bank job to become a freelance illustrator. In his thirties, shortly after gaining recognition as a book illustrator, Caldecott began working with Edmund Evans, an engraver and printer who experimented with color. Together they created the nursery storybooks for which Caldecott became famous. It is believed by some that Caldecott’s illustrations were the reason many nursery stories became popular. Caldecott traveled to the United States in December, 1885, with his wife, but the stormy sea voyage to New York and long train ride to Florida sapped his already frail health. He died in February, 1886 and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery in St. Augustine, Florida. His gravesite is maintained by the Randolph Caldecott Society of North America. -

2020 OLA Intermediate Sequoyah Smorgasbord the Assassination of Brangwain Spurge by M.T

2020 OLA Intermediate Sequoyah Smorgasbord The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge By M.T. Anderson and Eugene Yelchin Citation: Anderson, M.T., and Eugene Yelchin. The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge. Somerville: Candlewick Press, 2018. 544p. (Grades 5-8) Annotation: Elf historian, Brangwain Spurge is on a mission. Fly into the foul goblin kingdom, find his host Werfel the Archivist, deliver a gift of peace to Gogh the “Evil One” and send images back to the spymaster in Elfland. What could possibly go wrong? Told through a combination of prose, illustrations, and spymaster reports, this story delivers a humorous tale of misinformation, identity and acceptance. Booktalk: Elf Historian, Brangwain Spurge, has been catapulted (quite literally) into the arms of his nation’s greatest enemy, the goblin kingdom, on a mission to observe his surroundings and deliver a gift to the mysterious ruler Ghohg. Survival is optional. Eagerly awaiting the arrival of his invited guest is Goblin historian, Werfel the Archivist. Ever the patient and kind host, Werfel immerses Spurge in goblin culture. Meanwhile, ill-tempered Spurge is spying and sending Top Secret Transmission images back to the Order of the Clean Hand, but there is more to the story than meets the eye. This side-splitting illustrated novel is a fantastical comedy of manners that will tickle the readers’ funny bone while simultaneously asking them to think critically about the consequences of cultural perception, bias, and misinformation. Reviews: ● Booklist (Starred), 06/01/2018 ● -

Frankfurt 2020 Power of Story Catalog TABLE of CONTENTS

Frankfurt 2020 Power of Story Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS BOARD BOOKS 3 PICTURE BOOKS 6 ACORN, BRANCHES, AND CHAPTER BOOKS 44 GRAPHIC NOVELS 50 MIDDLE GRADE 60 YOUNG ADULT 103 NON FICTION 138 2 BOARD BOOKS 3 Power of Story Frankfurt 2020 Future Engineer (Future Baby) Lori Alexander, Allison Black Summary Flip a switch. Turn a gear. Could Baby be an engineer? Find out in this STEM-themed addition to the Future Baby series! Engineers want to know how things work. And so does Baby! Does Baby have what it takes to become an engineer? That's a positive! Discover all the incredible ways that prove Baby already has what it takes to become an engineer in whatever field they choose, be it electrical, mechanical, civil, or more! Includes lots of fun engineer facts to help foster curiosity and empower little ones to keep trying . Cartwheel Books 9781338312232 . and learning! Pub Date: 9/17/2019 Board Book Future Baby is an adorable board book series that takes a playful peek into an 24 Pages assortment of powerful careers and shows little ones how their current skills match up Ages 0 to 3, Grades P to P with the job at hand. With Future Baby, babies can be anything! Juvenile Nonfiction / Careers Series: Future Baby Contributor Bio 7 in H | 6.5 in W Before Lori was a children's book author, she worked in Human Resources, filling important positions like Mechanical Engineer, Cancer Biologist, Patent Attorney, and CFO. Luckily, Lori always found the right baby for the job! She is the author of the picture books Backhoe Joe and Famously Phoebe, and received a Sibert Honor for her chapter book All in a Drop. -

Macmillan Children's Publishing Group

macmillan children’s publishing group Frankfurt 2014 Farrar, Straus and Giroux Books for Young Readers Feiwel & Friends First Second Henry Holt Books for Young Readers Roaring Brook Press Swoon Reads and also including St. Martin’s Press and Tor/Starscape Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group Foreign Subsidiary Rights Contacts For Farrar, Straus and Giroux Books for Young Readers, First Second, Henry Holt Books for Young Readers, and Roaring Brook Press: Holly Hunnicutt Deputy Director, Subsidiary Rights 646-307-5297 [email protected] Samantha Metzger Assistant Manager, Subsidiary Rights 646-307-5298 [email protected] Miriam Miller Subsidiary Rights Assistant 646-307-5031 [email protected] For Feiwel & Friends, St. Martin’s Press & Tor/Starscape: Kerry Nordling VP, Director, Subsidiary Rights 646-307-5718 [email protected] Marta Fleming Subsidiary Rights Manager 646-307-5715 [email protected] Witt Phillips Foreign Rights Associate 646-307-5016 [email protected] Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group Jonathan Yaged, President and Publisher Editors: Farrar, Straus and Giroux Books for Young Readers Joy Peskin, Editorial Director Margaret Ferguson, Publisher, Margaret Ferguson Books Wesley Adams, Executive Editor Janine O’Malley, Senior Editor Grace Kendall, Editor Susan Dobinick, Associate Editor Feiwel & Friends Jean Feiwel, SVP, Publishing Director Liz Szabla, Editor-in-Chief Holly West, Associate Editor Anna Roberto, Associate Editor Swoon Reads Lauren Scobell, Editorial -

Newbery Award and Honor Book List

Association for Library Service to Children Newbery Medal Winners & Honor Books, 1922 – Present 2015 Medal Winner: The Crossover by Kwame Alexander (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) 2015 Honor Books: El Deafo by Cece Bell (Amulet Books, an imprint of ABRAMS) Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson ( Nancy Paulsen Books, an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) LLC) 2014 Medal Winner: Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures by Kate DiCamillo (Candlewick Press) 2014 Honor Books: Doll Bones by Holly Black (Margaret K. McElderry Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing) The Year of Billy Miller by Kevin Henkes (Greenwillow Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) One Came Home by Amy Timberlake (Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books) Paperboy by Vince Vawter (Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books) 2013 Medal Winner: The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate (HarperCollins Children's Books) 2013 Honor Books: Splendors and Glooms by Laura Amy Schlitz (Candlewick Press) Bomb: The Race to Build—and Steal—the World’s Most Dangerous Weapon by Steve Sheinkin (Flash Point/Roaring Brook Press) Three Times Lucky by Sheila Turnage (Dial/Penguin Young Readers Group) 2012 Medal Winner: Dead End in Norvelt by Jack Gantos (Farrar Straus Giroux) 2012 Honor Books: Inside Out & Back Again by Thanhha Lai (HarperCollins Children's Books, a division of HarperCollins Publishers) Breaking Stalin's Nose by Eugene Yelchin (Henry Holt and Company, LLC) 2011 Medal Winner: Moon over Manifest by Clare Vanderpool (Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children's Books) 2011 Honor Books: Turtle in Paradise by Jennifer L. -

Best Children's Books of the Year Twelve to Fourteen 2019 Edition

Best Children’s Books of the Year Twelve to Fourteen 2019 Edition Read Aloud Mature Content (11-15) Suggested Age Range Graphic Format - Diversity FICTION COMING OF AGE ADVENTURE AND MYSTERY *Be Prepared written and illustrated by Vera Brosgol, colors by Alec Dry Longstreth by Neal Shusterman and Jarrod Shusterman (First Second/Roaring Brook Press/Holtzbrinck, $22.99) (Simon & Schuster BFYR, $18.99) 978-1-4814-8196-0 978-1-62672-444-0 When California’s water supply is severely curtailed, a Struggling to fit in with American kids, immigrant Vera group of teens try desperately to survive as dire thirst tries Russian sleepaway camp. Can she survive the slowly drives citizens to lawlessness. (12-15) stinky latrines, forced marching, and mean girls? Clean- lined panel artwork. (11-13) Squirm by Carl Hiaasen *Between the Lines (Alfred A. Knopf BFYR/Random House/PRH, $18.99) by Nikki Grimes 978-0-385-75297-8 (Nancy Paulsen Books/Penguin YR/PRH, $17.99) A search for his dad sends Billy on a wild adventure to 978-0-399-24688-3 save endangered species and to discover the real In this companion to 2003’s Bronx Masquerade, meaning of family and love. (11-13) realistic, sensitively drawn characters grow to meet life’s challenges as they examine inner fears, pain, and loneliness via their poetry. (12-14) Trapped! (Framed! series) by James Ponti Confusion Is Nothing New (Aladdin/Simon & Schuster, $17.99) 978-1-5344-0891-3 by Paul Acampora Twelve-year-old undercover spies Florian and Margaret (Scholastic Press, $16.99) 978-1-338-20999-0 love their friendly FBI contact. -

Best of Best ALL Book Lists

Best of Best Workshop 2019 Book Lists 1 Best of the Best 2019 Middle Grades and YA Lists Realistic/Contemporary YA Fiction by Dr. Stacey Reese, West High School Top 10 Book List: 1. Internment - Samira Ahmed 2. Hot Dog Girl - Jennifer Dugan 3. The Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali - Sabina Khan 4. Two Can Keep a Secret - Karen McManus 5. White Rose - Kip Wilson 6. We Regret to Inform You - Ariel Kaplan 7. People Kill People - Ellen Hopkins 8. XL - Scott Brown 9. Jacked Up - Erica Sage 10. The Downstairs Girl - Stacey Lee **Patron Saints of Nothing - Randy Ribay (Bonus title!) Notable Titles: Dream Country by Shannon Gibney Let’s Go Swimming on Doomsday by Natalie C. Anderson How to Make Friends with the Dark by Kathleen Glasgow Field Notes on Love by Jennifer E. Smith Hope and Other Punchlines by Julie Buxbaum We Walked the Sky by Lisa Fiedler The Princess and the Fangirl by Ashley Poston If I’m Being Honest by Emily Wibberley and Austin Siegemund-Broka Dealing in Dreams by Lilliam Rivera If You’re Out There by Katy Loutzenhiser The Universal Laws of Marco by Carmen Rodrigues Death Prefers Blondes by Caleb Roehrig On the Come Up by Angie Thomas How It Feels to Float by Helena Fox Let Me Hear a Rhyme by Tiffany D. Jackson Somewhere Only We Know by Maureen Goo Ray needs and Delilah’s Midnite Matinee by Jeff Zentner Heroine by Mindy McGinnis With the Fire on High by Elizabeth Acevedo The Rest of the Story by Sarah Dessen What if It’s Us by Becky Albertalli and Adam Silvera The Music of What Happens by Bill Konigsberg Best of Best Workshop 2019 Book Lists 2 Young Adult Speculative Fiction Angela M. -

![The Best Children's Books of the Year [2019 Edition]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8515/the-best-childrens-books-of-the-year-2019-edition-11158515.webp)

The Best Children's Books of the Year [2019 Edition]

Bank Street College of Education Educate The Center for Children's Literature 4-4-2019 The Best Children's Books of the Year [2019 edition] Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee (2019). The Best Children's Books of the Year [2019 edition]. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl/ 9 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Center for Children's Literature by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Best Children’s Books of the Year 2019 Edition Books Published in 2018 BANK STREET COLLEGE OF EDUCATION THE BEST CHILDREN’S BOOKS OF THE YEAR 2019 EDITION OFBOOKS THE PUBLISHED YEAR IN 2018 SELECTED BY THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COMMITTEE THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COMMITTEE Jina Miharu Accardo Caren Leslie Marilyn Ackerman Elizabeth (Liz) Levy Rita Auerbach Muriel Mandell Alice Belgray Roberta Mitchell Jennifer Brown Caitlyn Morrissey Sheila Browning Karina Otoya-Knapp Allie Bruce Kathryn Payne Miriam Lang Budin Susan Pine Christie Clark Jaïra Placide Deb Cohen Candice Ralph Linda Colarusso Ellen Rappaport Ayanna Coleman Martha Rosen Carmen Colón Caroline Schill Becky Eisenberg Elizabeth C. Segal Gillian Engberg Charissa Sgouros Margery Fisher Dale Singer Helen Freidus Jo Stein Alex Grannis Susan Stires Melinda Greenblatt Hadassah Tannor Linda Greengrass Jane Thompson Catherine Hong Margaret Tice Todd Jackson Morika Tsujimura Andee Jorisch Leslie Wagner Gloria Koster Cynthia Weill Mollie Welsh Kruger Todd Zinn Patricia Lakin MEMBERS EMERITI Margaret Cooper Lisa Von Drasek MEMBERS ON LEAVE OR AT LARGE Beryl Bresgi Laurent Linn Ann Levine Rivka Widerman TIPS FOR PARENTS • Share your enjoyment of books with your child. -

Talking Book Topics May-June 2017

Talking Book Topics May–June 2017 Volume 83, Number 3 About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics is published bimonthly in audio, large-print, and online formats and distributed at no cost to participants in the Library of Congress reading program for people who are blind or have a physical disability. An abridged version is distributed in braille. This periodical lists digital talking books and magazines available through a network of cooperating libraries and carries news of developments and activities in services to people who are blind, visually impaired, or cannot read standard print material because of an organic physical disability. The annotated list in this issue is limited to titles recently added to the national collection, which contains thousands of fiction and nonfiction titles, including bestsellers, classics, biographies, romance novels, mysteries, and how-to guides. Some books in Spanish are also available. To explore the wide range of books in the national collection, visit the NLS Union Catalog online at www.loc.gov/nls or contact your local cooperating library. Talking Book Topics is also available in large print from your local cooperating library and in downloadable audio files on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site at https://nlsbard.loc.gov. An abridged version is available to subscribers of Braille Book Review. Library of Congress, Washington 2017 Catalog Card Number 60-46157 ISSN 0039-9183 About BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download. To use BARD, contact your cooperating library or visit https://nlsbard.loc.gov for more information.