India's Internal Security Situation Present Realities and Future Pathways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Krishna HO Sites.Xlsx

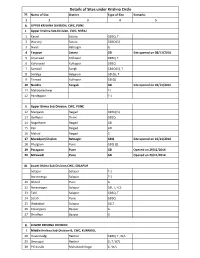

Details of Sites under Krishna Circle SL. Name of Site District Type of Site Remarks 12 3 4 5 A. UPPER KRISHNA DIVISION, CWC, PUNE I. Upper Krishna Sub‐Division, CWC, MIRAJ 1 Karad Satara GDSQ, T 2 Warunji Satara GDSQ (S) 3 Nivali Ratnagiri G 4 Targaon Satara GD Site opened on 08/11/2016 5 Arjunwad Kolhapur GDSQ, T 6 Kurunwad Kolhapur GDSQ 7 Samdoli Sangli GDSQ (S), T 8 Sadalga Belgaum GD (S), T 9 Terwad Kolhapur GD (S) 10 Nandre Sangali GD Site opened on 03/11/2016 11 Mahabaleshwar T‐I 12 Pandegaon T‐1 II. Upper Bhima Sub Division, CWC, PUNE 12 Mangaon Raigad GDSQ( S) 13 Badlapur Thane GDSQ 14 Nagathone Raigad GD 15 Pen Raigad GD 16 Mahad Raigad G 17 Muradpur/Chiplun Ratnagiri GDQ Site opened on 10/11/2016 18 Phulgaon Pune GDQ (S) 19 Paragaon Pune GD Opened on 29/11/2014 20 Mirawadi Pune GD Opened on 29/11/2014 III. Lower Bhima Sub Division,CWC, SOLAPUR Solapur Solapur T‐1 Boriomerga Solapur T‐1 21 Dhond Pune G 22 Narasingpur Solapur GD, T, FCS 23 Takli Solapur GDSQ, T 24 Sarati Pune GDSQ 25 Wadakbal Solapur GD,T 26 Kokangaon Bijapur G 27 Shirdhon Bijapur G B. LOWER KRISHNA DIVISION I Middle Krishna Sub‐Division‐II, CWC, KURNOOL 28 Huvenhedgi Raichur GDSQ, T, W/L 29 Deosugur Raichur G, T, W/L 30 P D Jurala Mahaboob Nagar G, W/L 31 K Agraharam Mahaboob Nagar G, T, W/L 32 Yadgir Yadgir GDSQ, T, W/L 33 Malkhed Gulbarga GDSQ, T 34 Jewangi Ranga Reddy G, T 35 Suddakallu Mahaboob Nagar GDSQ, T Opened on 20/11/2014 II. -

Malkangiri District

Orissa Review (Census Special) MALKANGIRI DISTRICT Andhra Pradesh on the east and Bastar district of Chhattisgarh state on the west. Malkangiri district is full of natural beauty. Long- The district having 5,791 sq. kms of th range hills, dense forests, rivers, streams, reservoir geographical area occupied the 13 rank in the and waterfalls are the major attractions of the state during 2001 Census. The average height of district. On the whole, the landscape of the district the district is 350m above the sea level having the presents a scenic beauty. highest elevation of 926 meters above Sea Level. Malkangiri district bears some The population of the district is mythological importance. It is situated in enumerated in 2001 Census to be 5.04 lakh of Dandakaranya region, where ‘Dandaka’ Rushi which 50.08 percent are males and 49.92 percent was residing. Lord Rama with Sita and Laxman females. The decadal growth rate during 1991- spent some years in this forest during their 14 years 2001 is 1.37 percent arithmetically averaged Banabasa. Some people say that the name annually. The area of the district is 5791 sq.km, Malkangiri has been derived from the name of a thus the calculated population density is 87 hill “Malyabanta giri”. Some historians believe that persons per sq km. The percentage of population the name Malkangiri takes after the name of a living in urban area is 6.87. The Scheduled Caste fort “Mallakimar danagarh” constructed by the population is 21.35 percent of the total population king Krishna Deo (1676-81) of Nandapur and of these the Namasudra (72.57 percent), kingdom. -

Seilen Haokip

Journal of North East India Studies Vol. 9(1), Jan.-Jun. 2019, pp. 83-93. Centennial Year of Kuki Rising, 1917-2017: Reflecting the Past Hundred Years Seilen Haokip The year 2017 marks the centennial year of the Kuki Rising, 1917-1919. The spirit of the rising that took place during First World War, also evident in Second World War, when the Kuki people fought on the side of the Axis group, has persisted. Freedom and self-determination remain a strong aspiration of the Kukis. One hundred years on, the history of the Kukis, segmented into three parts are: a) pre-British, b) British period, and c) present-day, in post-independent India. a) The pre-British period An era of self-rule marked the pre-British period. A nation in its own right, governance of Kuki country was based on traditional Haosa kivaipo (Chieftainship). Similar to the Greek-City states, each village was ruled by a Chief. Chieftainship, a hereditary institution, was complete with an administrative structure. The essential features comprised a two-tiered bicameral system: a) Upa Innpi or Bulpite Vaipohna (Upper House) and: b) Haosa Inpi or Kho Haosa Vaipohna (Lower House). Semang and Pachong (council of ministers and auxiliary members) assisted the Chief in the day- to-day administration. Cha’ngloi (Assistant), Lhangsam (Town Crier), Thiempu (High Priest and Judge), Lawm Upa (Minister of Youth & Cultural Affairs), Thihpu (Village Blacksmith) comprisedother organs of the Government (For details read Lunkim 2013). b) The British period The British administered Kuki country through the traditional institution of Chieftainship. However, the rights of the Chiefs were substantially reduced and house tax was imposed. -

DISTRICT-LEVEL STUDY on CHILD MARRIAGE in INDIA What Do We Know About the Prevalence, Trends and Patterns?

DISTRICT-LEVEL STUDY ON CHILD MARRIAGE IN INDIA What do we know about the prevalence, trends and patterns? PADMAVATHI SRINIVASAN NIZAMUDDIN KHAN RAVI VERMA International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), India DORA GIUSTI JOACHIM THEIS SUPRITI CHAKRABORTY United Nations International Children’s Educational fund (UNICEF), India International Center for Research on Women ICRW where insight and action connect 1 1 This report has been prepared by the International Center for Research on Women, in association with UNICEF. The report provides an analysis of the prevalence of child marriage at the district level in India and some of its key drivers. Suggested Citation: Srinivasan, Padmavathi; Khan, Nizamuddin; Verma, Ravi; Giusti, Dora; Theis, Joachim & Chakraborty, Supriti. (2015). District-level study on child marriage in India: What do we know about the prevalence, trends and patterns? New Delhi, India: International Center for Research on Women. 2 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), New Delhi, in collaboration with United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), New Delhi, conducted the District-level Study on Child Marriage in India to examine and highlight the prevalence, trends and patterns related to child marriage at the state and district levels. The first stage of the project, involving the study of prevalence, trends and patterns, quantitative analyses of a few key drivers of child marriage, and identification of state and districts for in-depth analysis, was undertaken and the report prepared by Dr. Padmavathi Srinivasan, with contributions from Dr. Nizamuddin Khan, under the strategic guidance of Dr. Ravi Verma. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms. -

India's Child Soldiers

India’s Child Soldiers: Government defends officially designated terror groups’ record on the recruitment of child soldiers before the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child Asian Centre For Human Rights India’s Child Soldiers: Government defends officially designated terror groups’ record on the recruitment of child soldiers before the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child A shadow report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict Asian Centre For Human Rights India’s Child Soldiers Published by: Asian Centre for Human Rights C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi 110058 INDIA Tel/Fax: +91 11 25620583, 25503624 Website: www.achrweb.org Email: [email protected] First published March 2013 ©Asian Centre for Human Rights, 2013 No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. ISBN : 978-81-88987-31-3 Suggested contribution Rs. 295/- Acknowledgement: This report is being published as a part of the ACHR’s “National Campaign for Prevention of Violence Against Children in Conflict with the Law in India” - a project funded by the European Commission under the European Instrument for Human Rights and Democracy – the European Union’s programme that aims to promote and support human rights and democracy worldwide. The views expressed are of the Asian Centre for Human Rights, and not of the European Commission. Asian Centre for Human Rights would also like to thank Ms Gitika Talukdar of Guwahati, a photo journalist, for the permission to use the photographs of the child soldiers. -

SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES a Biannual Journal of South Asian Studies

ISSN 0974 – 2514 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES A Biannual Journal of South Asian Studies Sixth Year of Publication Vol. 6 January – June 2013 No. 1 Editor Prof. Mohanan B Pillai SOCIETY FOR SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PONDICHERRY UNIVERSITY PUDUCHERRY, INDIA GUIDELINES FOR SUBMISSION OF MANUSCRIPTS Original papers that fall within the scope of the Journal shall be submitted by e- mail. An Abstract of the article in about 150 words must accompany the papers. The length of research papers shall be between 5000 and 7000 words. However, short notes, perspectives and lengthy papers will be published if the contents could justify. 1. The paper may be composed in MS-Words format, Times New Roman font with heading in Font Size 14 and the remaining text in the font size 12 with 1.5 spacing. 2. Notes should be numbered consecutively, superscripted in the text and attached to the end of the article. References should be cited within the text in parenthesis. e.g. (Sen 2003:150). 3. Spelling should follow the British pattern: e.g. ‘colour’, NOT ‘color’. 4. Quotations should be placed in double quotation marks. Long quotes of above 4 (four) lines should be indented in single space. 5. Use italics for title of the books, newspaper, journals and magazines in text, end notes and bibliography. 6. In the text, number below 100 should be mentioned in words (e.g. twenty eight). Use “per cent”, but in tables the symbol % should be typed. 7. Bibliography should be arranged alphabetically at the end of the text and must be complete in all respect. -

(PPMG) Police Medal for Gallantry (PMG) President's

Force Wise/State Wise list of Medal awardees to the Police Personnel on the occasion of Republic Day 2020 Si. Name of States/ President's Police Medal President's Police Medal No. Organization Police Medal for Gallantry Police Medal (PM) for for Gallantry (PMG) (PPM) for Meritorious (PPMG) Distinguished Service Service 1 Andhra Pradesh 00 00 02 15 2 Arunachal Pradesh 00 00 01 02 3 Assam 00 00 01 12 4 Bihar 00 07 03 10 5 Chhattisgarh 00 08 01 09 6 Delhi 00 12 02 17 7 Goa 00 00 01 01 8 Gujarat 00 00 02 17 9 Haryana 00 00 02 12 10 Himachal Pradesh 00 00 01 04 11 Jammu & Kashmir 03 105 02 16 12 Jharkhand 00 33 01 12 13 Karnataka 00 00 00 19 14 Kerala 00 00 00 10 15 Madhya Pradesh 00 00 04 17 16 Maharashtra 00 10 04 40 17 Manipur 00 02 01 07 18 Meghalaya 00 00 01 02 19 Mizoram 00 00 01 03 20 Nagaland 00 00 01 03 21 Odisha 00 16 02 11 22 Punjab 00 04 02 16 23 Rajasthan 00 00 02 16 24 Sikkim 00 00 00 01 25 Tamil Nadu 00 00 03 21 26 Telangana 00 00 01 12 27 Tripura 00 00 01 06 28 Uttar Pradesh 00 00 06 72 29 Uttarakhand 00 00 01 06 30 West Bengal 00 00 02 20 UTs 31 Andaman & 00 00 00 03 Nicobar Islands 32 Chandigarh 00 00 00 01 33 Dadra & Nagar 00 00 00 01 Haveli 34 Daman & Diu 00 00 00 00 02 35 Puducherry 00 00 00 CAPFs/Other Organizations 13 36 Assam Rifles 00 00 01 46 37 BSF 00 09 05 24 38 CISF 00 00 03 39 CRPF 01 75 06 56 12 40 ITBP 00 00 03 04 41 NSG 00 00 00 11 42 SSB 00 04 03 21 43 CBI 00 00 07 44 IB (MHA) 00 00 08 23 04 45 SPG 00 00 01 02 46 BPR&D 00 01 47 NCRB 00 00 00 04 48 NIA 00 00 01 01 49 SPV NPA 01 04 50 NDRF 00 00 00 00 51 LNJN NICFS 00 00 00 00 52 MHA proper 00 00 01 15 53 M/o Railways 00 01 02 (RPF) Total 04 286 93 657 LIST OF AWARDEES OF PRESIDENT'S POLICE MEDAL FOR GALLANTRY ON THE OCCASION OF REPUBLIC DAY-2020 President's Police Medal for Gallantry (PPMG) JAMMU & KASHMIR S/SHRI Sl No Name Rank Medal Awarded 1 Abdul Jabbar, IPS SSP PPMG 2 Gh. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

Yearbook Peace Processes.Pdf

School for a Culture of Peace 2010 Yearbook of Peace Processes Vicenç Fisas Icaria editorial 1 Publication: Icaria editorial / Escola de Cultura de Pau, UAB Printing: Romanyà Valls, SA Design: Lucas J. Wainer ISBN: Legal registry: This yearbook was written by Vicenç Fisas, Director of the UAB’s School for a Culture of Peace, in conjunction with several members of the School’s research team, including Patricia García, Josep María Royo, Núria Tomás, Jordi Urgell, Ana Villellas and María Villellas. Vicenç Fisas also holds the UNESCO Chair in Peace and Human Rights at the UAB. He holds a doctorate in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford, won the National Human Rights Award in 1988, and is the author of over thirty books on conflicts, disarmament and research into peace. Some of the works published are "Procesos de paz y negociación en conflictos armados” (“Peace Processes and Negotiation in Armed Conflicts”), “La paz es posible” (“Peace is Possible”) and “Cultura de paz y gestión de conflictos” (“Peace Culture and Conflict Management”). 2 CONTENTS Introduction: Definitions and typologies 5 Main Conclusions of the year 7 Peace processes in 2009 9 Main reasons for crises in the year’s negotiations 11 The peace temperature in 2009 12 Conflicts and peace processes in recent years 13 Common phases in negotiation processes 15 Special topic: Peace processes and the Human Development Index 16 Analyses by countries 21 Africa a) South and West Africa Mali (Tuaregs) 23 Niger (MNJ) 27 Nigeria (Niger Delta) 32 b) Horn of Africa Ethiopia-Eritrea 37 Ethiopia (Ogaden and Oromiya) 42 Somalia 46 Sudan (Darfur) 54 c) Great Lakes and Central Africa Burundi (FNL) 62 Chad 67 R. -

Malkangiri District, Orissa

Govt. of India MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MALKANGIRI DISTRICT, ORISSA South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar March, 2013 MALKANGIRI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl ITEMS Statistics No 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) 5791 ii. Administrative Divisions as on 31.03.2007 Number of Tehsil / Block 3 Tehsils, 7 Blocks Number of Panchayat / Villages 108 Panchayats 928 Villages iii Population (As on 2011 Census) 612,727 iv Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1437.47 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units Hills, Intermontane Valleys, Pediment - Inselberg complex and Bazada Major Drainages Kolab, Potteru, Sileru 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km.) a) Forest Area 1,430.02 b) Net Sown Area 1,158.86 c) Cultivable Area 1,311.71 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Ultisols, Alfisols 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROP Pulses etc. : 91,871 Ha 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Areas and Number of Structures) Dugwells 2,033 Ha Tube wells / Borewells Tanks / ponds 1,310 Ha Canals 71,150 Ha Other sources - Net irrigated area 74,493 Ha Gross irrigated area 74,493 Ha 7. NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB( As on 31-3-2011) No of Dugwells 29 No of Piezometers 4 10. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS Granites, Granite Gneiss, Granulites & its variants, Basic intrusives 11. HYDROGEOLOGY Major Water bearing formation Granites, Granite Gneiss Pre-monsoon Depth to water level during 2011 2.37 – 9.02 Post-monsoon Depth to water level during 2011 0.45 – 4.64 Long term water level trend in 10 yrs (2001-2011) in m/yr Mostly rise: 0.034 – 0.304(59%) Some Fall : 0.010 – 0.193(41%) 12. -

Article on Experience of My NCC Life Today I Am Going to Share My NCC Life Experience with You

Reg. No. AS18SDA133163 CSUO BISHAL DAS 4th ASSAM BATTALION NCC, KARIMGANJ KARIMGANJ COLLEGE, KARIMGANJ (ASSAM) Pin- 788710 Group SILCHAR NER DIRECTORATE Article on Experience of my NCC life Today I am going to share my NCC life experience with you. I had a dream to serve the country. That's why I want to join the Indian Army. When I passed HS, I first applied for recruitment in the Indian Army. 3rd January 2018 I was my first recruitment then I was physical and medical clear then I was very happy then gave us the date of written examination by recruitment agencie. I and one of my brothers, both, had passed, together, we both started preparing for the written examination. When we went to take the exam, my brother had a C-Certificate of NCC, that is why he did not have to give his written examination and I had to give the exam. When the results came, there was no Mara name in that list, but my brother's name was, My brother got a job in the Indian Army. Then I thought I would also join NCC. Then I reported in which college NCC is very good in our district. I got 4th Assam BN NCC at Karimganj in Karimganj College. Then I first joined the college, and to join the NCC, I approached the unit and told them to talk to the college's ANO. Then I saw the NCC enrollment notice in the college notic board and I contacted them and filed the form for joining NCC.He gave me the date of NCC selection 5th August 2018 I was very pleased. -

The Ion N) .$S S Is Are on Ed Ces Ive Ve Nd Ion T Is of an Ng to Ip. Ing Ing Cal an an Nd Is Nd * +DUDJRSDO This Note Is an Ac

Vol. 8(1) Socio-Legal Review 2012 The second one is establishing RHRIs at the sub-regional level through the THE M AOIST M OVEMENT AND active cooperation of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation THE INDIAN S TATE : M EDIATING PEACE (SAARC) in South Asia, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) LQ6RXWK(DVW$VLDDQGWKH3DFLÀF,VODQGV)RUXP 3,) LQWKH3DFLÀFUHJLRQ$V *+DUDJRSDO a starting point, the establishment of sub-regional human rights mechanisms is important for the protection of human rights in the region, and once there are This note is an account of the mediation/ negotiation at two separate sub-regional arrangements, they can work toward a human rights institution on kidnapping incidents- in Gurtendu in Andhra Pradesh in 1987 and the regional level. in Malkangiri in Orissa in February 2011 (in which the author was SHUVRQDOO\LQYROYHG ,WH[DPLQHVWKHUHVSRQVHRI WKH6WDWHWKHHQVXLQJ The third one is strengthening the role of the APF. The APF was established SHDFHWDONVDQGDQDO\]HVZKHWKHUDQ\GHPRFUDWLFVSDFHVZHUHRSHQHGXS to enhance the capacity of member NHRIs for better human rights practices consequently. at the national level and astrengthened domestic environment for effective implementation of international human rights standards. It will ultimately move I. BRIEF BACKGROUND AND H ISTORY OF THE NAXALITE M OVEMENT .............114 governments to establish RHRIs in the region. The development of the APF and its network of member NHRIs will also mobilize civil societies across the region 1. The Origin of the Movement ....................................................................114 to reach regional consensus for establishing RHRIs and the recognition that it is 2. The Politics of the State’s Response .........................................................115 necessary to have a regional human rights protection system.