Mennonites in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELECTORAL DISTRICTS Proposal for the Province of Ontario Published

ELECTORAL DISTRICTS Proposal for the Province of Ontario Published pursuant to the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act Table of Contents Preamble ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Process for Electoral Readjustment ................................................................................................ 3 Notice of Sittings for the Hearing of Representations .................................................................... 4 Requirements for Making Submissions During Commission Hearings ......................................... 5 Rules for Making Representations .................................................................................................. 6 Reasons for the Proposed Electoral Boundaries ............................................................................. 8 Schedule A – Electoral District Population Tables....................................................................... 31 Schedule B – Maps, Proposed Boundaries and Names of Electoral Districts .............................. 37 2 FEDERAL ELECTORAL BOUNDARIES COMMISSION FOR THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO PROPOSAL Preamble The number of electoral districts represented in the House of Commons is derived from the formula and rules set out in sections 51 and 51A of the Constitution Act, 1867. This formula takes into account changes to provincial population, as reflected in population estimates in the year of the most recent decennial census. The increase -

The Historical Development of Agricultural Policy and Urban Planning in Southern Ontario

Settlement, Food Lands, and Sustainable Habitation: The Historical Development of Agricultural Policy and Urban Planning in Southern Ontario By: Joel Fridman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Geography, Collaborative Program in Environmental Studies Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto © Copyright by Joel Fridman 2014 Settlement, Food Lands, and Sustainable Habitation: The Historical Development of Agricultural Policy and Urban Planning in Southern Ontario Joel Fridman Masters of Arts in Geography, Collaborative Program in Environmental Studies Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto 2014 Abstract In this thesis I recount the historical relationship between settlement and food lands in Southern Ontario. Informed by landscape and food regime theory, I use a landscape approach to interpret the history of this relationship to deepen our understanding of a pertinent, and historically specific problem of land access for sustainable farming. This thesis presents entrenched barriers to landscape renewal as institutional legacies of various layers of history. It argues that at the moment and for the last century Southern Ontario has had two different, parallel sets of determinants for land use operating on the same landscape in the form of agricultural policy and urban planning. To the extent that they are not purposefully coordinated, not just with each other but with the social and ecological foundations of our habitation, this is at the root of the problem of land access for sustainable farming. ii Acknowledgements This thesis is accomplished with the help and support of many. I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Harriet Friedmann, for kindly encouraging me in the right direction. -

Consent Agenda 2020.01.20

THE CORPORATION OF THE TOWNSHIP OF ST. JOSEPH CONSENT AGENDA JANUARY 20,2021 I a. Ken Leffler Receive Re: Request to open part of the walking trail for golf carts. 2-* a. Town of Lincoln Receive Re: Supporting Resolution re: Cannabis Retail Stores ;-t c. Region of Peel / Township of Huron-Kinloss Support Re: Property Tax Exemptions for Veteran Clubs 34a Loyalist Township Support Re: funding for community Groups and service clubs affected by pandemic lo ^t(e City of St. Catharines Receive Re: Development Approval Requirements for Landfills (Bill 197) 1213. Corporation of the Municipality of West Grey Support Re: Schedule 8 of the Provincial Budget Bill22g, Support and Recovery from COVtn- 19 Act tq - lJ g. Town of Kingsville / United Counties of Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry Support Re: Letter of Support for Small Businesses Itf 9 h. Municipality if Mississippi Mills Support Re: Request for Revisions to Municipal Elections Huron North Community Economic Alliance Receive 2cat' Re: Member Update for November 2020 eej General Hillier Receive Re: COVID-I9 Vaccination update 8?24U. Peter Julian, Mp - New Westminster - Burnaby Support Re: Canada Pharmacare Act M,d Solicitor General Receive Re: Community Safety and Well-Being Plan deadline extension Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs Receive *l-X^.(J/ ' Re: Updates to Ontario Wildlife Damage Compensation Program (OWDCP) Qq$A. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs Receive Re: Amendments to Drainage Act A4'o Ministry of Solicitor General Receive Re: Declaration of Provincial Emergency 3v41p Ministry of Transportation Receive Re: connecting the North: A Draft Transportation Plan for Northem ontario J6-L{l U. -

Brookfield Place Calgary East Tower

BROOKFIELD PLACE CALGARY EAST TOWER UP TO 78,162 SF FOR SUBLEASE 225 - 6th Avenue SW CALGARY, ALBERTA ALEX BROUGH JAMES MCKENZIE CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD ULC Executive Vice President Vice President 250 - 6th Avenue SW, Suite 2400 Calgary, Alberta T2P 3H7 403 261 1186 403 261 1140 403 261 1111 [email protected] [email protected] cushmanwakefield.com FOR SUBLEASE Brookfield Place Calgary - East Tower 225 - 6th Avenue SW | Calgary, AB Property Details Building Amenities Address 225 - 6th Avenue SW • +15 connected to Stephen Avenue Place & Year Built 2017 Bow Valley Square • Large urban plaza features a south facing Landlord Brookfield Place (Calgary) LP landscaped courtyard with extensive Property Management Brookfield Properties Canada seating and common areas Management LP • In-house Porter Service Total Building Size 1,417,577 SF • Bike storage facility/shower Number of Floors 56 • LEED GOLD Core & Shell Certification Average Floor Plate 26,300 SF - Low Rise 27,800 SF - Mid Rise Elevators 10 per rise Ceiling Height 9’ Parking Ratio 1:3,000 SF Leasing Particulars Sublandlord: Cenovus Energy Inc. Area Available: Fl 20: 26,477 SF SUBLEASED Fl 21: 26,474 SF SUBLEASED Fl 22: 26,473 SF SUBLEASED Fl 23: 25,755 SF SUBLEASED Fl 24: 26,412 SF Virtual Tour Fl 25: 25,704 SF Fl 26: 11,736 SF Fl 27: 27,521 SF SUBLEASED Fl 28: 14,310 SF Total: 78,162 SF Rental Rate: Market sublease rates Additional Rent: $19.35/SF (2021 LL estimate) Parking: 1 stall per 3,000 SF As at March 2020 Bike Facilities Plan FOR SUBLEASE Brookfield Place Calgary -

Fire Department Members in Good Standing Addington Highlands Fire

Fire Department Members in good standing Addington Highlands Fire Adelaide Metcalfe Fire Department Adjala-Tosorontio Fire Department Y Ajax Fire Y Alberton Fire Alfred & Plantagenet Y Algonquin Highlands Fire Alnwick/Haldlmand Fire Y Amherstburg Fire Department Y Arcelor-Mittal Dofasco Argyle Fire Armstrong Fire Arnprior Fire Arran Elderslie (Chelsey) Fire Arran Elderslie (Paisley) Fire Arran Elderslie (Tara) Fire Asphodel-Norwood Fire Assiginack Fire Athens Fire Y Atikokan Fire Augusta Fire Y Aviva Insurance Canada Y Aweres Fire Aylmer Fire Department Y Baldwin Fire Barrie Fire & Emergency Services Y Batchawana Bay Fire Bayfield Fire Bayham Fire & Emergency Services Y Beausoleil Fire Beckwith Twp. Fire Belleville Fire Y Biddulph-Blanshard Fire Billings & Allan Fire Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport Black River Matheson Fire Blandford - Blenheim Fire Blind River Fire Bonfield Volunteer Fire Department Bonnechere Valley Fire Department Bracebridge Fire Department Y Bradford West Gwillinbury Fire & Emergency Services Y Brampton Fire Department Y Brantford Fire Department Y Brighton District Fire Department Britt Fire Department Brock Twp. Fire Department Y Brockton Fire Department Y Brockville Fire Department Y Brooke-Alvinston District Fire Department Y Bruce Mines Bruce Mines Fire Department Y Bruce Power Brucefield Area Fire Department Brudenell, Lyndoch & Raglan Fire Department Burk's Falls & District Fire Department Y Burlington Fire Department Y Burpee & Mills Fire Department Caledon Fire & Emergency Services Y Callander Fire Department -

On Target for Stroke Prevention and Care

Ontario Stroke Evaluation Report 2014 On Target for Stroke Prevention and Care SUPPLEMENT: ONTARIO STROKE REPORT CARDS June 2014 ONTARIO STROKE EVALUATION REPORT 2014: ON TARGET FOR STROKE PREVENTION AND CARE Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences ONTARIO STROKE EVALUATION REPORT 2014: ON TARGET FOR STROKE PREVENTION AND CARE Ontario Stroke Evaluation Report 2014 On Target for Stroke Prevention and Care SUPPLEMENT: ONTARIO STROKE REPORT CARDS Authors Ruth Hall, PhD Beth Linkewich, MPA, BScOT, OT Reg (Ont) Ferhana Khan, MPH David Wu, PhD Jim Lumsden, BScPT, MPA Cally Martin, BScPT, MSc Kay Morrison, RN, MScN Patrick Moore, MA Linda Kelloway, RN, MN, CNN(c) Moira K. Kapral, MD, MSc, FRCPC Christina O’Callaghan, BAppSc (PT) Mark Bayley, MD, FRCPC Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences i ONTARIO STROKE EVALUATION REPORT 2014: ON TARGET FOR STROKE PREVENTION AND CARE Publication Information Contents © 2014 Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences INSTITUTE FOR CLINICAL EVALUATIVE SCIENCES 1 ONTARIO STROKE REPORT CARDS (ICES). All rights reserved. G1 06, 2075 Bayview Avenue Toronto, ON M4N 3M5 32 APPENDICES This publication may be reproduced in whole or in Telephone: 416-480-4055 33 A Indicator Definitions part for non-commercial purposes only and on the Email: [email protected] 35 B Methodology condition that the original content of the publication 37 C Contact Information for High-Performing or portion of the publication not be altered in any ISBN: 978-1-926850-50-4 (Print) Facilities and Sub-LHINs by Indicator way without the express written permission ISBN: 978-1-926850-51-1 (Online) 38 D About the Organizations Involved in this Report of ICES. -

Status and Extent of Aquatic Protected Areas in the Great Lakes

Status and Extent of Aquatic Protected Areas in the Great Lakes Scott R. Parker, Nicholas E. Mandrak, Jeff D. Truscott, Patrick L. Lawrence, Dan Kraus, Graham Bryan, and Mike Molnar Introduction The Laurentian Great Lakes are immensely important to the environmental, economic, and social well-being of both Canada and the United States (US). They form the largest surface freshwater system in the world. At over 30,000 km long, their mainland and island coastline is comparable in length to that of the contiguous US marine coastline (Government of Canada and USEPA 1995; Gronewold et al. 2013). With thousands of native species, including many endemics, the lakes are rich in biodiversity (Pearsall 2013). However, over the last century the Great Lakes have experienced profound human-caused changes, includ- ing those associated with land use changes, contaminants, invasive species, climate change, over-fishing, and habitat loss (e.g., Bunnell et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2015). It is a challenging context in terms of conservation, especially within protected areas established to safeguard species and their habitat. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a protected area is “a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associat- ed ecosystem services and cultural values” (Dudley 2008). Depending on the management goals, protected areas can span the spectrum of IUCN categories from highly protected no- take reserves to multiple-use areas (Table 1). The potential values and benefits of protected areas are well established, including conserving biodiversity; protecting ecosystem structures and functions; being a focal point and context for public engagement, education, and good governance; supporting nature-based recreation and tourism; acting as a control or reference site for scientific research; providing a positive spill-over effect for fisheries; and helping to mitigate and adapt to climate change (e.g., Lemieux et al. -

Of 5 Polling District Polling District Name Polling Place Polling Place Local Government Ward Scottish Parliamentary Cons

Polling Polling District Local Government Scottish Parliamentary Polling Place Polling Place District Name Ward Constituency Houldsworth Institute, MM0101 Dallas Houldsworth Institute 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Dallas, Forres, IV36 2SA Grant Community Centre, MM0102 Rothes Grant Community Centre 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray 46 - 48 New Street, Rothes, AB38 7BJ Boharm Village Hall, MM0103 Boharm Boharm Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Mulben, Keith, AB56 6YH Margach Hall, MM0104 Knockando Margach Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Knockando, Aberlour, AB38 7RX Archiestown Hall, MM0105 Archiestown Archiestown Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray The Square, Archiestown, AB38 7QX Craigellachie Village Hall, MM0106 Craigellachie Craigellachie Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray John Street, Craigellachie, AB38 9SW Drummuir Village Hall, MM0107 Drummuir Drummuir Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Drummuir, Keith, AB55 5JE Fleming Hall, MM0108 Aberlour Fleming Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Queens Road, Aberlour, AB38 9PR Mortlach Memorial Hall, MM0109 Dufftown & Cabrach Mortlach Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Albert Place, Dufftown, AB55 4AY Glenlivet Public Hall, MM0110 Glenlivet Glenlivet Public Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Glenlivet, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EJ Richmond Memorial Hall, MM0111 Tomintoul Richmond Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Tomnabat Lane, Tomintoul, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EZ McBoyle Hall, BM0201 Portknockie McBoyle Hall 2 - Keith and Cullen Banffshire and Buchan Coast Seafield -

In Again! MANITOBA Miles of the Coasts, Baysi Creeks, Or the ?0.Tb of June Next, Ly Cents Pey Rouvillc Bordeur Harbors of Canada

(=55335 VOL- If. REVELSTOKE, B. 0., MARO-#, 7,1891. No. 37. Cornwall and Storoiont Bergen LIISEItALy. %ty, ftootway Star Dundas Boss QSTAaUQ, Durham E Craig Addington Dawson WEST KOOTENAY DISTRICT. Elgin E Ingram Braut, North Somervilla SATUBDAY. MARCH. 7,1891 Frontenao Kirkpatrick " South Puterson KOTICE. Notieo is hereby given that all Glengarry McLennan Bolhwell Mills alluvial claims legally held in tho Gt'enville, South ft*'1' Brueo, wost Rjwlan 1 West Koptenay District, will be laid TIIF. Vancouver presa is a unit Grey, East Sproule Durham, west Beith All Mining Claims, Qtucr than Mineral overfrom the 1st of October to the in opposing the granting of Loe,,tio..s,legidlyheld in this District, Grey, North Mason Elgin, west Casey lst day of June "ensuing according charters lo tho American rail under the Mineral Act, 1884 and Amend to the conditions of Section 116 of Haldimand Montagno Kssex, North McGregor. ments, mav belaid overfroml.lh day of tho Mineral Act. ways which propose tupping Halton Ilonderscn " Bontb Allan October till the 1st d„y; of June, ne?t, O, 0, TUNSTALL, Southern Kootenay. In discus Hamilton ..,, McKay and Ryckman Grey, South Landerkia y 91 subject to the provisions of tho said 29 Gold Commissioner, sing the quoslion the News-Ad Hastings, North Bowell Hastings, East Biirdetta Hoyelstoke, September 26th, 1890, vertiser oiij's: "Wc ato there- •' Wost Corby Huron, East MctJonaU Kingston Sir John Macdonsld " South McMillan Gold Commissioner. NOTICE. " fore face to face with tho simple Donald, East Kootenay, " question—ia it desirablo lo aiith- Lanibton, East , Moncriof " west Cameron Lanark, North , Jeinjpaon Kent Campbell September IM1), 1800, " orize tho construction of roads Notice is hereby given that Rich Lanark, South , .Haggart Lanark, North. -

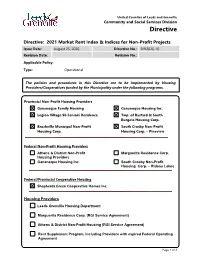

2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects

United Counties of Leeds and Grenville Community and Social Services Division Directive Directive: 2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects Issue Date: August 25, 2020 Directive No.: DIR2020-10 Revision Date: Revision No.: Applicable Policy: Type: Operational The policies and procedures in this Directive are to be implemented by Housing Providers/Cooperatives funded by the Municipality under the following programs. Provincial Non-Profit Housing Providers Gananoque Family Housing Gananoque Housing Inc. Legion Village 96 Seniors Residence Twp. of Bastard & South Burgess Housing Corp. Brockville Municipal Non-Profit South Crosby Non-Profit Housing Corp. Housing Corp. – Pineview Federal Non-Profit Housing Providers Athens & District Non-Profit Marguerita Residence Corp. Housing Providers Gananoque Housing Inc. South Crosby Non-Profit Housing Corp. – Rideau Lakes Federal/Provincial Cooperative Housing Shepherds Green Cooperative Homes Inc. Housing Providers Leeds Grenville Housing Department Marguerita Residence Corp. (RGI Service Agreement) Athens & District Non-Profit Housing (RGI Service Agreement) Rent Supplement Program, including Providers with expired Federal Operating Agreement Page 1 of 3 United Counties of Leeds and Grenville Community and Social Services Division Directive Directive: 2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects Issue Date: August 25, 2020 Directive No.: DIR2020-10 Revision Date: Revision No.: BACKGROUND Each year, the Ministry provides indices for costs and revenues to calculate subsidies under the Housing Services Act (HSA). The indices to be used for 2021 are contained in this directive. PURPOSE The purpose of this directive is to advise housing providers of the index factors to be used in the calculation of subsidy for 2021. ACTION TO BE TAKEN Housing providers shall use the index factors in the table below to calculate subsidies under the Housing Services Act, 2011 (HSA) on an annual basis. -

Area 83 Eastern Ontario International Area Committee Minutes June 2

ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AREA 83 EASTERN ONTARIO INTERNATIONAL Area 83 Eastern Ontario International Area Committee Minutes June 2, 2018 ACM – June 2, 2018 1 ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AREA 83 EASTERN ONTARIO INTERNATIONAL 1. OPENING…………………………………………………………………………….…………….…4 2. REVIEW AND ACCEPTANCE OF AGENDA………………………………….…………….…...7 3. ROLL CALL………………………………………………………………………….……………….7 4. REVIEW AND ACCEPTANCE OF MINUTES OF September 9, 2017 ACM…………………7 5. DISTRICT COMMITTEE MEMBERS’ REPORTS ……………………………………………....8 District 02 Malton……………………………………………………………………………….…….. 8 District 06 Mississauga……………………………………………………………………….…….. 8 District 10 Toronto South Central…………………………………………………………….….…. 8 District 12 Toronto South West………………………………………………………………….…. 9 District 14 Toronto North Central………………………………………………………………..….. 9 District 16 Distrito Hispano de Toronto…………………………………………………….………..9 District 18 Toronto City East……………………………………………………………………........9 District 22 Scarborough……………………………………………………………………………… 9 District 26 Lakeshore West………………………………………………………………….……….10 District 28 Lakeshore East……………………………………………………………………………11 District 30 Quinte West…………………………………………………………………………….. 11 District 34 Quinte East……………………………………………………………………………… 12 District 36 Kingston & the Islands……………………………………………………………….… 12 District 42 St. Lawrence International………………………………………………………………. 12 District 48 Seaway Valley North……………………………………………………………….……. 13 District 50 Cornwall…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 District 54 Ottawa Rideau……………………………………………………………………………. 13 District 58 Ottawa Bytown…………………………………………………………………………… -

Report, Activities, 2000, Timmins, Sault Ste Marie

Ontario Geological Survey Open File Report 6050 Report of Activities, 2000 Resident Geologist Program Timmins Regional Resident Geologist Report: Timmins and Sault Ste. Marie Districts 2001 ONTARIO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open File Report 6050 Report of Activities, 2000 Resident Geologist Program Timmins Regional Resident Geologist Report: Timmins and Sault Ste. Marie Districts by B.T. Atkinson, M. Hailstone, G. Wm. Seim, A.C. Wilson, D.M. Draper, D. Farrow, P. Hope, R. Debicki and G. Yule 2001 Parts of this publication may be quoted if credit is given. It is recommended that reference to this publication be made in the following form: Atkinson, B.T., Hailstone, M., Seim, G. Wm., Wilson, A.C., Draper, D.M., Farrow, D., Hope, P., Debicki, R. and Yule, G. 2001. Report of Activities 2000, Resident Geologist Program, Timmins Regional Resident Geologist Report: Timmins and Sault Ste. Marie Districts; Ontario Geological Survey, Open File Report 6050, 116p. e Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2001 e Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2001. Open File Reports of the Ontario Geological Survey are available for viewing at the Mines Library in Sudbury, at the Mines and Minerals Information Centre in Toronto, and at the regional Mines and Minerals office whose district includes the area covered by the report (see below). Copies can be purchased at Publication Sales and the office whose district includes the area covered by the report. Al- though a particular report may not be in stock at locations other than the Publication Sales office in Sudbury, they can generally be obtained within 3 working days. All telephone, fax, mail and e--mail orders should be directed to the Publi- cation Sales office in Sudbury.