Bodybuilders to the World: Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESOLUTION INDEX Cont'd Resolution No. 63-5 the Board Has Designated the Scott Research Laboratories, Inc., As An- Authorized Control Testing Laboratory

- 4 - RESOLUTION INDEX Cont'd Resolution No. 63-5 The Board has designated the Scott Research Laboratories, Inc., as an- authorized control testing laboratory. Resolution No. 63-6 The Board approved the State-B.R. Higbie contract number 6137 for $2,46$'. Resolution No. 63-7 United Air Cleaner Division, Novo Industrial Corporation filed an application for certificate of approval for a crankcase emission control device on February 28, 1962. Resolution No. 63-8 Humber, Ltd. filed an application for a certificate of approval for a crankcase emission control device on October 29, 1962. Resolution No. 63-9 WHEREAS, every possible means must be used to effect a significant reduction in air pollution because of continued growth of Los Angeles and the State and, to give immediate 6 attention to the need for mass rapid transit in Los Angeles W County. Resolution No. 63-10 Fiat s.P.A. filed an application for a certificate of A approval for a crankcase emission control system on 1/22/63. W Resolution No. 63-11 Renault filed an application for a certificate of approval for a crankcase emission control system on 1/21/63. Resolution No. 63-12 Resolution exempting foreign cars from provisions of • Section 24390, Rover Motor Cars (England) Aston Martin (England) Lagonda (England). Resolution No. 63-13 Norris-Thermador filed an application for a certificate of approval for a crankcase emission control system on 2/19/63. Resolution No. 63-14 Resolution to exempt from Article 3 of this Chapter mo.tor driven cycles, implements of husbandry and•••••••••••••••· Reso_lution No. -

The Jensen Interceptor: Chrysler-Powered British Luxury

The Jensen Interceptor: Chrysler- Powered British Luxury Allan and Richard Jensen's auto business was started before World War II, which interrupted production until 1950, when their first Interceptor was made. At the time, they made Austin bodies under contract, and the first Interceptor resembled an Austin A40 (the Jensens built bodies for a string of cars that included the Volvo P1800, Sunbeam Tiger, and Austin-Healey.) The first Interceptor used a 4 liter Austin in-line six, and was produced in small numbers for over a decade. Jensen also used Nash Twin-Ignition Eight engines for a time, and the 1962 C-V8 used a Chrysler 361 B-block engine. A number of these early Jensens made their way to the US before and after World War II. The next version kept the basic C-V8 chassis, but changed styling. Initially, an in-house convertible design was planned, but chief engineer Kevin Beattie argued for an Italian flavor. Proposals were taken from different design houses, with Carozzeria Touring winning out with a fastback coupe incorporating a rounded tail, but that house was unable to finalize the design. Vignale, instead, provided prototype and initial production bodies, rendered in steel, on CV-8 chassis sent to them by Jensen. Turnaround was quick - about four months - so the new Interceptors could be shown in London in October 1966. Jensen later used the jigs and tools, which were sent by Vignale to the West Bromwich factory. The body had two doors, a low beltline, and fishbowl rear glass in a handsome 2+2 design. -

PROJECT DP208» Bei As- Ton Martin Lagonda Ltd. Unter Der Nummer W

VOLVO P1800 - POWERED BY ASTON MARTIN 1961 WAR DER START von «PROJECT DP208» bei As- gere Zeit fuhr. Da letztendlich der Motor für VOLVO zurückzuführen. Da nach Rücksprachen mit VOLVO ton Martin Lagonda Ltd. Unter der Nummer W/O 24076 zu teuer war und auch kein Gewichtsvorteil resultierte, Schweden und auch dem VOLVO Importeur wie JEN- wurde das Motorenprojekt unter Federführung von Mr. wurde das Projekt wahrscheinlich 1964 eingestellt». SEN MOTORS die original Chassisnummer nicht eru- John Wyer, dem damaligen General Manager von As- SEIT 1974, laut Artikel aus CLASSIC and SPORTSCAR iert werden konnte, wurde in der Schweiz nach einem ton Martin Lagonda Ltd., genau am 9. März 1961 dem von Jonathan Wood, gelten die verbliebenen 2 Moto- Fahrzeug gesucht das bei JENSEN MOTORS in England Motorenkonstrukteur Mr. Tadek Marek übergeben. ren als verschollen. Auch wurde der dritte Motor mit gebaut wurde. Die Suche war erfolgreich, fand man DER AUFTRAG lautete: Dieses Projekt beinhaltet der eingeschlagenen Nummer 3 im Block und einer 1 doch in der Nähe von Basel ein solches Fahrzeug das das Design und Konstruktion von drei 2,5Ltr. 4-Zylin- im Zylinderkopf gesucht. mit grossem Aufwand restauriert und in der Farbe BRG der Motoren unter Verwendung von möglichst vielen hervorragend zu diesem Projekt passt. GENAU DIESER MOTOR wurde uns per Telefon von Werkzeugen, Gussformen und Teilen des bestehenden Herrn Wolfgang Buchholz, einem langjährigen Vertrau- DA AUSSER DEN DAMALIGEN PROJECT-SHEETS 3,7 Ltr. 6-Zylinder Motor, d.h. des DB4 Motors. ten unserer Firma, 2003 angeboten, da das Interesse keine Zeichnungen oder Fotos über dieses Fahrzeug bis DIE KOSTEN für dieses Projekt wurden mit £ 3000.— an diesem für die meisten ASTON MARTIN-Enthusias- Dato zu finden waren, haben wir uns entschlossen mit- beziffert, d.h. -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

December Oxford Sale Collectors’ Motor Cars and Automobilia Monday 9 December 2013 Bonhams Oxford

December Oxford Sale Collectors’ Motor Cars and Automobilia Monday 9 December 2013 Bonhams Oxford Collectors’ Motor Cars and Automobilia Monday 9 December 2013 Bonhams, Oxford Shipton-on-Cherwell, OX5 1JH Bonhams Bids Enquiries Customer Services 101 New Bond Street +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Motor Cars Monday to Friday 8am to 6pm London W1S 1SR +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 bonhams.com To bid via the internet please visit +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax www.bonhams.com [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder Viewing information including after-sale Sunday 8 December Please note that bids should Automobilia collection and shipment 10am to 4pm be submitted no later than +44 (0) 8700 273 621 Monday 9 December Friday 6 December. Thereafter bids +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax Please see back of catalogue from 9am should be sent direct to Bonhams [email protected] for important notice to bidders office at the sale venue. Sale times 21274 Enquiries on view Sale Number: Automobilia 10am We regret that we are unable to and sale days Motor Cars 1.30pm accept telephone bids for lots with a +44 (0) 1865 853 640 Illustrations low estimate below £500. Absentee +44 (0) 1865 372 722 fax Front cover: Lot 356 bids will be accepted. New bidders Back cover: Lot 320 must also provide proof of identity £20 + p&p when submitting bids. Failure to do Catalogue: so may result in your bids not being processed. Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. -

Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant Charlotte-Mecklenburg County Local Landmark Designation

Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant Charlotte-Mecklenburg County Local Landmark Designation Prepared by MacRostie Historic Advisors In partnership with CAMP North End 1. Name and Location of the Property: Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant (later referred to as Building No. 1 during U.S Army Quartermaster Depot ownership) located at 1824 Statesville Avenue, Charlotte, NC, 29206. 2. Name and Address of the Present Owner of the Property: Thomas Mann Camp Landowner, LP 1776 Statesville Avenue Charlotte, NC 28206 3. Representative Photographs of the Property: The report contains representative photographs of the property. 4. Map Depicting the Location of the Property: The report contains a map depicting the location of the property. 5. Current Deed Book Reference to the Property: The current deed to the property is recorded in Deed Book 31440 Page 554. The tax parcel number of the property is 07903105. 6. A Brief Historic Sketch of the Property: The report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Caroline Wilson and Kendra Waters. 7. A Brief Physical Description of the Property: The report contains a brief physical description of the property prepared by Caroline Wilson and Kendra Waters. 8. Documentation of Why and in What Ways the Property Meets the Criteria for Designation Set Forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5. a. Special Significance in Terms of its History, Architecture, and/or Cultural Importance: The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission judges that the Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant possesses special significance in terms of the City of Charlotte. The Commission bases its judgement on the following considerations: i. -

Kjell Qvale Dies at 94; Married U.S. to Sports Cars - the New York Times

9/21/2020 Kjell Qvale Dies at 94; Married U.S. to Sports Cars - The New York Times https://nyti.ms/183z3Rp Kjell Qvale Dies at 94; Married U.S. to Sports Cars By Douglas Martin Nov. 12, 2013 Kjell Qvale, who fell in love with a forest-green, wire-wheel MG sports car in the 1940s and went on to become one of the earliest American importers of European cars, ultimately selling a million automobiles as a distributor and dealer, died on Nov. 1 in San Francisco. He was 94. His family announced the death. As a recently discharged Navy veteran, the Norwegian-born Kjell Qvale (pronounced shell KAH-vah-leh) entered the car business in 1946, using $8,500 in savings to invest in a Jeep dealership in Alameda, Calif. He had no particular passion for cars at the time; to him, this was strictly a business proposition. It was also strictly business when he made a trip to New Orleans to meet with an importer to discuss expanding his line by adding James motorcycles, a not-terribly-fast British make known for its Jeep-like practicality. There, Mr. Qvale found himself standing on a street corner when “this goofy-looking car pulls up to the curb in front of me,” he said in an interview in 2008. He asked the driver where it was made. “England,” the driver said. The car was the MG, and the driver turned out to be the importer of motorcycles he had come to see. He gave Mr. Qvale a ride. It also turned out that the importer was looking for someone to market MGs in Northern California. -

Jensen Motors Lotus Europa Twin Cam Competition Manual

LOTUS EUROPA TWIN CAM COMPETITION MANUAL PREPARED BY: JENSEN MOTORS, INC. 19200 SUSANA RD. COMPTON, CALIF. 90221 ( i ) FOREWORD Modifications of the type described in this booklet and/or the use of the Lotus Europe Twin-Cam for competition render the vehicle warranty null and void. Jensen Motors, Inc. and/or Lotus Cars, Ltd. will not be held responsible for any damage or injury, which may occur in the following of any procedure or changes outlined in the following text. ( ii ) CONTENTS FOREWORD............................................................................................... ( i ) INTRODUCTION....................................................................................... ( ii ) Section CHASSIS...................................................................................................... 1 SUSPENSION AND STEERING................................................................ 4 BRAKING SYSTEM................................................................................... 11 COOLING SYSTEMS (WATER, OIL AND DRIVER)............................. 12 ENG I NE..................................................................................................... 14 TRANSMISSION AND CLUTCH.............................................................. 15 BODY........................................................................................................... 21 ELECTRICAL.............................................................................................. 21 FUEL SYSTEM........................................................................................... -

The Automobile in Japan

International and Japanese Studies Symposium The Automobile in Japan Stewart Lone, Associate Professor of East Asian History, Australian Defence Force Academy, Canberra Japan and the Age of Speed: Urban Society and the Automobile, 1925-30 p.1 Christopher Madeley, Chaucer College, Canterbury Kaishinsha, DAT, Nissan and the British Motor Vehicle Industry p.15 The Suntory Centre Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines London School of Economics and Political Science Discussion Paper Houghton Street No. IS/05/494 London WC2A 2AE July 2005 Tel: 020-7955-6699 Preface A symposium was held in the Michio Morishima room at STICERD on 7 April 2005 to discuss aspects of the motor industry in Japan. Stewart Lone discussed the impact which the introduction of the motor car had on Japan’s urban society in the 1920s, especially in the neighbourhood of the city of Kyoto. By way of contrast, Christopher Madeley traced the relationship between Nissan (and its predecessors) and the British motor industry, starting with the construction of the first cars in 1912 by the Kaishinsha Company, using chassis imported from Swift of Coventry. July 2005 Abstracts Lone: The 1920s saw the emergence in Kansai of modern industrial urban living with the development of the underground, air services; wireless telephones, super express trains etc. Automobiles dominated major streets from the early 1920s in the new Age of Speed. Using Kyoto city as an example, the article covers automobile advertising, procedures for taxis, buses and cars and traffic safety and regulation. Madeley: Nissan Motor Company had a longer connection with the British industry than any other Japanese vehicle manufacturer. -

The Realanorak Quiz ANSWERS

The REAL Anorak Quiz ANSWERS Round 1:- Advertising Slogans No. Question Answer 1 Safety Fast MG 2 You can depend on An Austin it! 3 Hand built by robots Fiat (Strada) (as opposed to the Austin Ambassador, which was “Hand Built by Roberts” in the “Not the Nine o’Clock News”, sketch. See https://www.youtube.com/watc h?v=FU-tuY0Z7nQ ) 4 Everything we do is Ford driven by you No. Question Answer 5 Grace…. Space…. Jaguar Pace…. (It’s a shame they have forgotten the first one of these!) 6 The pioneer and still Morgan Runabout the best 7 The only car with its Wolseley name in lights (from its patented illuminated radiator badge) 8 Zoom, zoom, zoom Mazda 9 Made like a gun Royal Enfield (motorcycle) No. Question Answer 10 The power of dreams Honda 11 Takes your breath Peugeot away 12 The car in front is a Toyota 13 Sure as the sunrise Albion lorries (Should have been easy for Dire Straits fans. See “Border Riever”: https://www.youtube.com/watc h?v=Gi35yMzUuVg ) 14 Ugly is only skin Volkswagen (Beetle) deep 15 It’s a ….. honest Skoda No. Question Answer 16 The ultimate driving BMW machine 17 The silent sports car Bentley 18 As old as the Riley industry as modern as the hour 19 Vorsprung durch Audi Technik 20 The relentless Lexus pursuit of perfection Round 2:- Manufacturers’ Names No. Question Answer 1 The Latin for “I roll” Volvo (from the company’s origin as a subsidiary of SKF Bearings) 2 The founders name and an early hillclimb Aston-Martin location (Lionel Martin-Aston Clinton hillclimb) 3 Derived from the Norman, Fulk de Breant’s Vauxhall Hall, which gave its name to an area of London 4 The founder’s daughter Mercedes 5 Chemical symbol for Aluminium and the Alvis Latin for “Strong” (first made aluminium pistons) 6 A high level of achievement Standard 7 General Purpose Vehicle Jeep 8 The owner and his famous shell bearings Vanwall (Tony Vandervell/Thin wall bearings) 9 Named after a dealership in Oxford which MG sold tuned versions of cars made locally. -

Bentley Speed Six the Ultimate in Power, Luxury and Competition Pedigree

FORD MODEL T MAZDA COSMO FORD XR6 TF R47.00 incl VAT May 2017 BENTLEY SPEED SIX THE ULTIMATE IN POWER, LUXURY AND COMPETITION PEDIGREE STYLE & SUBSTANCE COMMEMORATING ENZO RENAULT’S CARAVELLE AND R8/10 FERRARI ENZO – FRENCH FLAIR THE MAN AND THE CAR DICKON DAGGITT | BMW 2002 RESTORED | DENNIS GUSCOTT PCC_Porsche Classic_210x276.qxp_Porsche 210x275 2017/04/05 11:46 AM Page 1 www.porschecapetown.com The first Porsche built boasted exceptional everyday practicality. Nothing has changed. Porsche Centre Cape Town. As a Porsche Classic Partner, our goal is the maintenance and care of historic Porsche vehicles. With expertise on site, Porsche Centre Cape Town is dedicated to ensuring your vehicle continues to be what it has always been: 100% Porsche. Our services include: • Classic Sales • Classic Body Repair • Genuine Classic Parts • Classic Service Porsche Centre Cape Town Corner Century Avenue and Summer Greens Drive, Century City Tel: 021 555 6800 CONTENTS — CARS BIKES PEOPLE AFRICA — MAY 2017 WORK & PLAY THE ROTARY CLUB 03 Editor’s point of view 64 Mazda Cosmo turns 50 CLASSIC CALENDAR DYNAMIC BEST-SELLER 06 Upcoming events for 2017 70 A modern classic – Mazda MX-5 NEWS & EVENTS PADKOS 08 All the latest from the classic scene 72 Backseat Driver – a female perspective THE MAGIC FORMULA 18 50 years of Formula Ford racing A CLASSIC RACER 74 Bike racer and tuner Dennis Guscott CARBS & COFFEE 22 All the ingredients THE FAMOUS FELINE’S FOUNDER 78 Sir William Lyons COMMEMORATING ENZO 24 Celebrating Ferrari’s 70th THE PERFECT CLASSIC with an Enzo -

Alan and Richard Jensen Produced Their First Car in 1928 When They

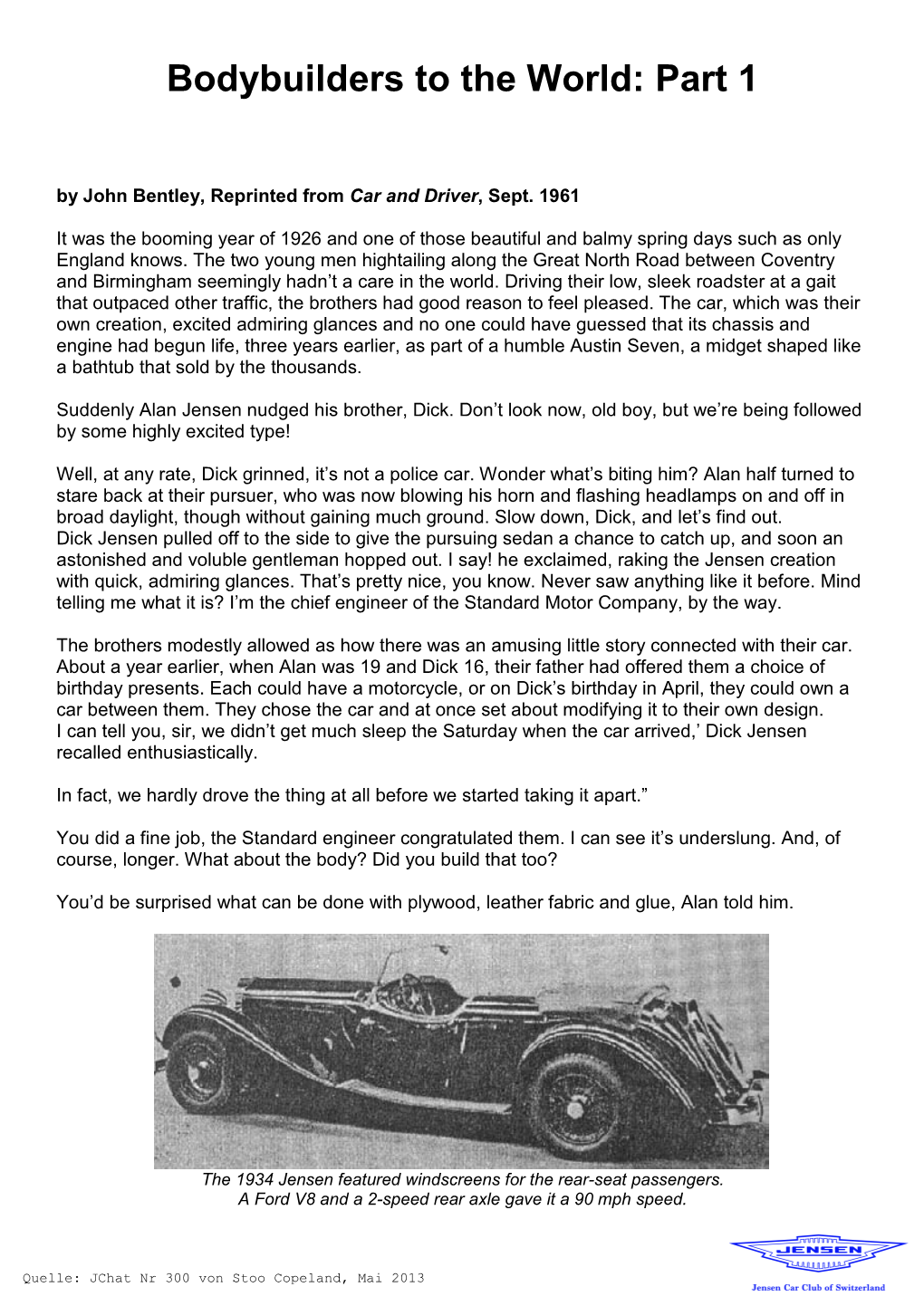

Alan and Richard Jensen produced their first car in 1928 when they converted a five year old Austin 7 Chummy Saloon into a very stylish two seater with cycle guards, louvred bonnet and boat-tail. This was soon sold and replaced with another Austin 7. Then came a car produced on a Standard chassis followed by a series of specials based on the Wolseley Hornet, a popular sporting small car of the time. The early 1930s saw the brothers becoming joint managing directors of commercial coachbuilders W J Smith & Sons and within three years the name of the company was changed to Jensen Motors Limited. Soon bodywork conversions followed on readily available chassis from Morris, Singer, Standard and Wolseley. Jensen’s work did not go unnoticed as they received a commission from actor Clark Gable to produced a car on a US Ford V8 chassis. This stylish car led to an arrangement with Edsel Ford for the production of a range of sports cars using a Jensen designed chassis and powered by Ford V8 engines equipped with three speed Ford transmissions. Next came a series of sporting cars powered by the twin-ignition straight eight Nash engine or the Lincoln V12 unit. On the commercial side of the business Jensen’s were the leaders in the field of the design and construction of high-strength light alloys in commercial vehicles and produced a range of alloy bodied trucks and busses powered by either four-cylinder Ford engines, Ford V8s, or Perkins diesels. World War Two saw sports car production put aside and attentions were turned to more appropriate activities such as producing revolving tank gun turrets, explosives and converting the Sherman Tank for amphibious use in the D-Day invasion of Europe.