3426 Zamalek SC V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

477520 1 En Bookbackmatter 313..348

Table of Cases Decisions by the Court of Arbitration for Sport CAS 86/1, Niederhasli HC v. Ligue Suisse de Hockey sur Glace (LSHG) CAS 86/02, International Olympic Committee (IOC) & NOC CAS 91/53, G. v. Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) CAS 91/56, S v. Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) CAS 92/63, Gundel v. Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) CAS 92/71, SJ v. Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) CAS 92/73, N v. Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) CAS 92/80, B. v. Fédération Internationale de Basketball (FIBA) CAS 92/81, L v. Y. SA CAS 92/86, W. v. Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) CAS 93/103, SC Langnau v. Ligue Suisse de Hockey sur Glace (LSHG) CAS 93/109, Fédération Française de Triathlon (FFTri) & International Triathlon Union (ITU) CAS 95/122, National Wheelchair Basketball Association (NWBA) v. International Paralympic Committee (IPC) CAS 94/123, Fédération Internationale de Basketball (FIBA) v. W. & Brandt Hagen e. V. (Brandt Hagen) CAS 94/128, Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) & Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano (CONI) CAS 94/129, USA Shooting & Quigley v. Union Internationale de Tir (UIT) CAS 94/132, Puerto Rico Amateur Baseball Federation (PRABF) v. USA Baseball (USAB) CAS 95/141, Chagnaud v. Fédération Internationale de Natation Amateur (FINA) CAS 95/142, Lehtinen v. Fédération Internationale de Natation Amateur (FINA) CAS 95/144, Comités Olympiques Européens (COE) CAS 95/145, Federation Y CAS 96/149, Cullwick v. Fédération Internationale de Natation Amateur (FINA) © T.M.C. ASSER PRESS and the author 2019 313 J. Lindholm, The Court of Arbitration for Sport and Its Jurisprudence, ASSER International Sports Law Series, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-285-9 314 Table of Cases CAS 95/150, Volkers v. -

Das Grosse Vereinslexikon Des Weltfussballs

1 RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS ALLE ERSTLIGISTEN WELTWEIT VON 1885 BIS HEUTE AFRIKA & ASIEN BAND 1 DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS DES VEREINSLEXIKON GROSSE DAS BAND 1 AFRIKA & ASIEN RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS BAND 1 AFRIKA UND ASIEN Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National- bibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Copyright © 2019 Verlag Die Werkstatt GmbH Lotzestraße 22a, D-37083 Göttingen, www.werkstatt-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Gestaltung: René Köber Satz: Die Werkstatt Medien-Produktion GmbH, Göttingen ISBN 978-3-7307-0459-2 René Köber RENÉRené KÖBERKöber Das große Vereins- DasDAS große GROSSE Vereins- LEXIKON VEREINSLEXIKONdesL WEeXlt-IFKuOßbNal lS des Welt-F ußballS DES WELTFUSSBALLSBAND 1 BAND 1 BAND 1 AFRIKAAFRIKA UND und ASIEN ASIEN AFRIKA und ASIEN Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute 15 00015 000 Vereine Vereine aus aus 6 6 000 000 Städten/Ortschaften und und 228 228 Ländern Ländern 15 000 Vereine aus 6 000 Städten/Ortschaften und 228 Ländern 1919 000 000 farbige Vereinslogos Vereinslogos 19 000 farbige Vereinslogos Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Stadien, Erfolge, Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Spielerauswahl Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, -

Sadd Face High-Flying Sepahan, Duhail Take on Taawoun

NNBABA | Page 5 TTENNISENNIS | Page 7 Team LeBron Tunisian Jabeur edge Team upsets Riske Giannis to win in opening All-Star thriller round Tuesday, February 18, 2020 CRICKET Jumada II 24, 1441 AH Faf du Plessis GULF TIMES quits as South Africa skipper SPORT Page 2 FOOTBALL / AFC CHAMPIONS LEAGUE Sadd face high-fl ying Sepahan, Duhail take on Taawoun ‘I saw Sepahan’s last match, and it was a surprise to me that they won by 4-0. There is no doubt it will be a tough match’ By Sports Reporter Doha l Sadd will aim to get the fi rst win of their cam- paign, while Al Duhail will look to keep the Awinning momentum going as the Qatari giants return to AFC Champions League action today. Sadd will have the advantage of playing at home as they play Iran’s Sepahan at the Jassim bin Hamad Stadium at 6:35pm. For Duhail, though, it’s an away game against Saudi side Al Taawoun at the King Abdullah Sport City Stadium in Buraidah. Sadd, the 2011 AFC Champions League winners came away from Riyadh with a 2-2 draw against Al Nassr in their fi rst match, while Sepahan stunned Al Ain 4-0 in their opening match. On the match eve, Sadd’s head coach Xavi Hernandez said he expected a diffi cult match against Sepahan and was surprised by Iranian side’s one-sided win against Al Ain. “I saw Sepahan’s last match, and it was a surprise to me that they won by 4-0. -

Masarykova Univerzita Brno Fakulta Sportovních Studií

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA BRNO FAKULTA SPORTOVNÍCH STUDIÍ Bakalářská práce Historie fotbalu v Africe Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Luboš Vrábel SEBS, 5. sem., rok 2009 Učo: 21389 Čestné prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci, vypracoval sám. Souhlasím, aby práce byla uložena na Masarykově univerzitě v Brně v knihovně Fakulty sportovních studií a zpřístupněna ke studijním účelům. …………………… podpis Poděkování: Děkuji za pomoc a odborné vedení při zpracování této bakalářské práce. Obsah 1. Úvod……………………………………………………………………………………5 2. Fotbal v koloniální Africe……………………………………………………………...6 2.1 Počátky kolonialismu…………………………………………………….….6 2.2 Rasismus……………………………………………………………………. 7 2.3 Koloniální společnost………………………………………………………..8 3. Fotbal a rozvoj………………………………………………………………………….9 3.1 Východ ( Etiopie, Súdán, Keňa)…………………………………………… 9 3.2 Západ ( Kamerun, Nigérie, Ghana, Kongo)………………………………… 9 3.3 Sever ( Egypt, Tunisko, Maroko)………………………………………….... 10 3.4 Jih ( Jihoafrická Republika)…………………………………………………. 10 4. Fotbal a politika………………………………………………………………………... 12 5. Africké organizace……………………………………………………………………... 15 5.1 CAF …………………………………………………………………………… 15 5.2 MYSA…………………………………………………………………………. 16 5.3 playsoccer …………………………………………………………………….. 16 6.Africké fotbalové hvězdy………………………………………………………………. 17 6.1. Didier Yves Drogba Tébily…………………………………………………… 17 6.2. Roger Milla……………………………………………………………………. 17 6.3. Mahmoud El-Khatib…………………………………………………………… 17 6.4. Samuel Eto'o Fils………………………………………………………………. 18 7.Nejslavnější Africké kluby ……………………………………………………………. 19 8.Soutěže…………………………………………………………………………………. -

Commentary No.353 Thursday, 10 March 2016 Conviction of Egyptian Soccer Fans Slams Door on Potential Political Dialogue James M

Commentary No.353 Thursday, 10 March 2016 Conviction of Egyptian soccer fans slams door on Potential political dialogue James M. Dorsey Nanyang Technological University, Singapore leeting hopes that Egypt’s militant, street battled-hardened soccer fans may have breached general-turned-president Abdel Fattah Al Sisi’s repressive armour were dashed with the F sentencing of 15 supporters on charges of attempting to assassinate the controversial head of storied Cairo club Al Zamalek SC. Although the sentences of one year in prison handed down by a Cairo court were relatively light by the standards of a judiciary that has sent hundreds of regime critics to the gallows and condemned hundreds more to lengthy periods in jail, it threatens to close the door to a dialogue that had seemingly been opened, if only barely, by Al Sisi. Al Sisi’s rare gesture came in a month that witnessed three mass protests, two by soccer fans in commemoration of scores of supporters killed in two separate, politically loaded incidents, and one by medical doctors – an exceptional occurrence since Al Sisi’s rise to power in a military coup in 2013 followed by a widely criticized election and the passing of a draconic anti-protest law. In a telephone call to a local television in reaction to a 1 February gathering of Ultras Ahlawy, the militant support group of Zamalek arch rival Al Ahli SC, in honour of 72 of their members who died in 2012 in a brawl in the Suez Canal city of Port Said, Al Sisi offered the fans to conduct an investigation of their own. -

FIVB2021BU19-Dailybulletin-01.Pdf

Daily Bullen No. 01 23th AUG Tehran, 23 August 2021 BU19 WCH / Strict Adherence to the Covid-19 Guidelines Dear Participating Teams, We are very happy and grateful for your participation in this challenging tournament. As we eagerly anticipate the beginning of the championship, we would like to kindly ask you to strictly follow the Covid-19 Guidelines. We advise you to remind your players not to gather in groups in the common areas and while waiting for trasportation to the training/competition halls. Also, please avoid being close to other teams, especially in the restaurant, where many people have their masks off. The health and well-being of our athletes and all participants is our highest priority! We would also ask you to be swift and cooperative while maintaning the training schedule. Please always be sure to enter and leave the training halls on time, as our schedules are very tight! Thank you for your consideration and cooperation and best of luck in your fixtures! FIVB TECHNICAL DELEGATES FIVB Volleyball Boys' U19 World Championship VOLLEYBALL - Matches calendar No Phase Teams Date Hour City Hall 1 B CZE - COL 24-Aug-2021 10:00 Tehran Hall 1 2 C THA - BUL 24-Aug-2021 10:00 Tehran Hall 2 3 A NGR - IND 24-Aug-2021 13:00 Tehran Hall 1 4 D EGY - ARG 24-Aug-2021 13:00 Tehran Hall 2 5 B ITA - BRA 24-Aug-2021 16:00 Tehran Hall 1 6 D GER - CUB 24-Aug-2021 16:00 Tehran Hall 2 7 A IRI - GUA 24-Aug-2021 19:00 Tehran Hall 1 8 C RUS - BEL 24-Aug-2021 19:00 Tehran Hall 2 9 B BRA - BLR 25-Aug-2021 10:00 Tehran Hall 1 10 D ARG - GER 25-Aug-2021 -

8 Hassan Mostafa Zamalek SC, Egyptian Premier

8 Hassan Mostafa Zamalek SC, Egyptian Premier League (Egypt) not currently plaing for national team The profile for Hassan Mostafa Date of birth: 20.11.1979 Place of birth: Giza Age: 31 Height: 1,75 Nationality: Egypt Position: Midfield - Defensive Midfield Foot: right 352.000 £ Market value: 400.000 € Market value Details of market value National team career SN National team Matches Goals 21 Egypt 29 2 More info about Hassan Mostafa Contract until: 30.06.2011 Debut (Club): 07.08.2009* "Performance data of current season Competition Matches Goals Assists Minutes CAF-Champions League 2 - - - 1 161 Egyptian Premier League 16 2 1 - 5 1367 Total: 18 2 1 - 6 1528 Performance data for season 10/11 Competition Matches CAF-Champions League 2 - - - - - - - 1 - 161 Egyptian Premier League 16 2 - 1 7 - - - 5 684 1367 Total: 18 2 - 1 7 - - - 6 764 1528 CAF-Champions League - 10/11 pl. Match Result 1 Club Africain Tunis - Zamalek SC 4 : 2 90 2 Zamalek SC - Club Africain Tunis 2 : 1 71 70 Egyptian Premier League - 10/11 pl. Match Result 4 Zamalek SC - Ismaily SC 3 : 2 38 90 5 Zamalek SC - El Gouna FC 1 : 1 72 90 6 Smouha SC - Zamalek SC 1 : 3 x 89 88 7 Zamalek SC - Arab Contractors SC 1 : 0 90 8 Masr El Makasa - Zamalek SC 3 : 4 90 11 Zamalek SC - Masry Port Said 1 : 0 90 12 El Ahly Cairo - Zamalek SC 0 : 0 51 65 64 13 Zamalek SC - Ittehad Alexandria 4 : 3 90 14 Wadi Degla FC - Zamalek SC 0 : 2 1 90 15 Zamalek SC - Entag El Harby 0 : 0 90 16 Zamalek SC - Harras El Hodoud 2 : 1 1 90 17 Petrojet - Zamalek SC 1 : 2 1 52 90 18 Zamalek SC - Enppi Club 0 : 0 90 19 Ismaily SC - Zamalek SC 0 : 0 81 80 20 El Gouna FC - Zamalek SC 2 : 1 28 56 55 22 Arab Contractors SC - Zamalek SC 2 : 3 19 86 85 Performance data for season 08/09 Competition Matches Egyptian Premier League 14 - - - 1 - - 3 7 - 981 WM-Qualifikation Afrika 2 - - - 1 - - 2 - - 55 Total: 16 - - - 2 - - 5 7 - 1036 Egyptian Premier League - 08/09 pl. -

Govt Keen on Quality Education: Minister

TUESDAY AUGUST 27, 2019 DHU AL-HIJJAH 26, 1440 VOL.12 NO. 4723 QR 2 FINE Fajr: 3:53 am Dhuhr: 11:36 am HIGH : 39°C Asr: 3:05 pm Maghrib: 6:00 pm LOW : 32°C Isha: 7:30 pm MAIN BRANCH LULU HYPER SANAYYA ALKHOR Business 10 Sports 14 Doha D-Ring Road Street-17 M & J Building MATAR QADEEM MANSOURA ABU HAMOUR BIN OMRAN Oil falls as US-Iran optimism IAAF World Championships Near Ahli Bank Al Meera Petrol Station Al Meera faces US-China trade deal hopes Doha 2019 medals revealed alzamanexchange www.alzamanexchange.com 44441448 200 MILLION MAN-HOURS AT QATAR 2022 WORLD CUP STADIUM PROJECTS Govt keen on quality Qatar, Mozambique education: Minister sign air transport agreement Several steps taken QNA to improve quality of DOHA education: Hammadi QATAR and Mozambique have signed the final agree- QNA ment for comprehensive air DOHA transport which allows the national carrier to operate MINISTER of Education and any number of flights be- Higher Education HE Dr Mo- tween the two countries. hammed bin Abdul Wahed The agreement was al Hammadi has stressed the signed by Qatar’s Civil Avia- quality of the educational pro- tion Authority (CAA) Chair- cess, including the services Minister of Education and Higher Education HE Dr Mohammed bin man HE Abdulla bin Nasser provided by the ministry to the Abdul Wahed al Hammadi at a meeting on Monday. Turki al Subaey and Vice public. Minister of Transport and Workers celebrate 200 million man-hours at eight Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup stadium projects. -

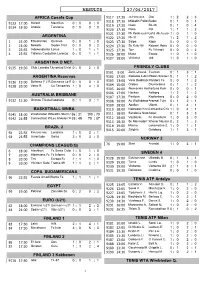

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

RESULTS 27/06/2017 AFRICA Cosafa Cup 9117 17:30 Js Hercules Otp 12: 2: 3 9118 17:30 Mikkelin PalloilSudet 01: 0: 1 9133 17:00 Malawi Mauritius 00: 0: 0 9119 17:30 Nups Bk-46 01: 0: 4 9134 19:30 Angola Tanzania 00: 0: 0 9120 17:30 Pepo Ktp 11: 1: 2 9121 17:30 Pk Keski-uusimLahti Ak./kuusy 10: 1: 0 ARGENTINA 9122 17:30 Pk-37 Vifk 12: 1: 2 1 23:00 Estudiantes Quilmes 00: 1: 0 9123 17:30 Salpa Kapa 00: 0: 0 2 23:00 Newells Godoy Cruz 00: 0: 2 9124 17:30 Sc Kufu-98 Kajaani Haka 00: 0: 0 3 23:55 Independiente Lanus 10: 1: 1 9125 17:30 Tpv Fc Viikingit 00: 0: 2 4 23:55 Talleres CordoSan Lorenzo 00: 1: 1 9126 18:00 Musa Espoo 10: 1: 0 9127 18:00 Villiketut Jbk 10: 1: 0 ARGENTINA D MET. 9135 19:30 Club Leandro NJuventud Unida00: 2: 0 FRIENDLY CLUBS 9101 9:00 Zenit-izhevsk Tyumen 01: 3: 1 ARGENTINA Reservas 9102 17:00 Zaglebie LubinPogon Szczeci 01: 1: 2 Vejle Boldklub Randers Fc 00: 1: 3 9136 15:00 Defensa Y J R.Gimnasia Lp R 00: 0: 0 9103 13:00 Orebro Djurgardens 01: 1: 2 9138 20:00 Velez R. Ca Temperley 10: 4: 0 9104 15:00 9105 16:00 Alemannia AacFortuna Koln 00: 0: 1 Hacken Aalborg AUSTRALIA BRISBANE 9106 17:00 12: 1: 2 9107 17:30 Partizan Kapfenberg 00: 2: 0 9132 12:30 Grange ThistleCapalaba 01: 3: 1 9108 18:00 Ac WolfsbergeArsenal Tula 01: 2: 1 9109 18:00 Apollon Ujpest 01: 4: 1 BASKETBALL WNBA 9110 18:00 Napredak KrusConcordia Chia10: 4: 1 9141 18:00 Washington WSeattle Storm W56: 31 100: 70 9111 18:00 Sandecja NowyApoel 01: 3: 3 9142 23:55 Connecticut WLos Angeles W39: 45 79: 87 9112 18:00 Vozdovac Fc Orenburg 10: 3: 0 9113 18:30 Sc Mannsdorf Wiener Neusta 02: 1: 3 BRAZIL 2 9114 19:00 Malmo Lokomotiva Z. -

ICCA Report 8.Indb

INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL FOR COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION REPORT OF THE CROSS-INSTITUTIONAL TASK FORCE ON GENDER DIVERSITY IN ARBITRAL APPOINTMENTS AND PROCEEDINGS THE ICCA REPORTS NO. 8 2020 ICCA is pleased to present the ICCA Reports series in the hope that these occasional papers, prepared by ICCA interest groups and project groups, will stimulate discussion and debate. INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL FOR COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION REPORT OF THE ASIL-ICCAINTERNATIONAL COUNCIL JOINT FOR TASK FORCE ON COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION ISSUE CONFLICTS IN INVESTOR-STATE ARBITRATION REPORT OF THE CROSS-INSTITUTIONAL TASKTHE FORCE ICCA ON REPORTS GENDER DIVERSITY NO. 3 IN ARBITRAL APPOINTMENTS AND PROCEEDINGS THE17 ICCA March REPORTS 2016 NO. 8 2020 with the assistance of the Permanentwith the Courtassistance of Arbitration of the PermanentPeace Palace, Court Theof Arbitration Hague Peace Palace, The Hague www.arbitration-icca.org www.arbitration-icca.org Published by the International Council for Commercial Arbitration <www.arbitration-icca.org>, on behalf of the Cross-Institutional Task Force on Gender Diversity in Arbitral Appointments and Proceedings ISBN 978-94-92405-20-3 All rights reserved. © 2020 International Council for Commercial Arbitration © International Council for Commercial Arbitration (ICCA). All rights reserved. ICCA and the Cross-Institutional Task Force on Gender Diversity in Arbitral Appointments and Proceedings wish to encourage the use of this Report for the promotion of diversity in arbitration. Accordingly, it is permitted to reproduce or copy this Report, provided that the Report is reproduced accurately, without alteration and in a non-misleading con- text, and provided that the authorship of the Cross-Institutional Task Force on Gender Diversity in Arbitral Appointments and Proceedings and ICCA’s copyright are clearly acknowledged. -

Sporting Prowess on Show Qatar Turns Into a Huge Sporting Arena As Tens of Thousands Join NSD Activities That Promote Active and Healthy Lifestyles

QatarTribune Qatar_Tribune QatarTribuneChannel qatar_tribune WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 12, 2020 JUMADA AL-AKHIR 18, 1441 VOL.13 NO. 4867 QR 2 Fajr: 4:54 am Dhuhr: 11:48 am DUSTY Asr: 3:01 pm Maghrib: 5:26 pm HIGH : 17°C Isha: 6:56 pm LOW : 13°C Gulf / ME 9 Business 11 Sports 14 Syria regime helicopter downed LNG infrastructure to Al Duhail cruise in as Turkey’s Erdogan warns of see faster build-up Doha; Al Sadd held 2-2 ‘very heavy price’ for any attack than pipelines: GECF by Al Nassr in Riyadh AMIR LEADS NATION IN CELEBRATING NATIONAL SPORT DAY SPORTING PROWESS ON SHOW Qatar turns into a huge sporting arena as tens of thousands join NSD activities that promote active and healthy lifestyles TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK DOHA THE Amir HH Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al Thani led the nation in celebrating National Sport Day (NSD) on Tuesday as the country turned into a The Amir HH Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al Thani takes part in a walk at Lusail promenade with world champions, athletes, Qatari Women’s Sports Committee players and Aspire Academy students on Tuesday. huge sports arena with tens of thousands of people turning up at different venues across Qatar to take part in activities and programmes that foster healthy lifestyles. The Amir led a walking and jogging exercise at Lusail promenade with a number of world champions, Olym- pic athletes, Qatari Women’s Sports Committee players and Aspire Academy students. The Father Amir HH Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al Thani participated in NSD ac- tivities as he carried out a walk- ing exercise at Al Shaqab. -

RUSE and VARNA, BULGARIA POOLS B and D

RUSE AND VARNA, BULGARIA POOLS B and D Bulletin 3 10/09/2018 1 FIVB Volleyball Men's World Championship O-2bis Team registration BRA - Brazil Weight Height Highest reach [cm] National selections Shirt no Last name First name Shirt name Pos. Birthdate Club [kg] [cm] Spike Block WC OG Oth. Tot. 1 C Rezende Bruno Mossa Bruno S 02-Jul-1986 76 190 323 302 Lube 7 2 20 29 2 Santos Isac Isac MB 13-Dec-1990 99 208 339 306 Sada Cruzeiro - - 8 8 3 Carbonera Eder Eder MB 19-Oct-1983 107 205 360 330 SESI-SP 3 - 5 8 5 Loh Lucas Eduardo Lucas Loh WS 18-Jan-1991 83 195 336 320 SESI-SP - - - - 7 Arjona William William S 31-Jul-1979 78 186 300 295 SESI-SP - 1 - 1 8 De Souza Wallace Wallace OP 26-Jun-1987 87 198 344 318 SESC-RJ 14 1 37 52 9 Hoss Thales Thales L 26-Apr-1989 74 190 320 303 Funvic Taubaté - - - - 12 Fonteles Luiz Felipe Marques Lipe WS 19-Jun-1984 100 198 351 340 SESI-SP 13 - 37 50 13 Souza Maurício M. Souza MB 29-Sep-1988 93 209 344 323 SESC-RJ - - - - 14 Souza Douglas Douglas WS 20-Aug-1995 75 199 338 317 Funvic Taubaté - - - - 15 Barreto Silva Carlos Eduardo Kadu WS 08-Aug-1994 90 200 348 340 Vibo Valentia 8 - - 8 16 Saatkamp Lucas Lucas MB 06-Mar-1986 101 209 340 321 Funvic Taubaté 16 - 37 53 17 Guerra Evandro M. Evandro OP 27-Dec-1981 106 207 359 332 Sada Cruzeiro 7 - 17 24 22 Reis Nascimento Maique Maique L 16-Jul-1997 76 182 310 255 Minas Tenis Clube - - - - OFFICIALS COLORS STATISTICS Team manager: Fernando Castro Maroni Main: Yellow Data Minimum Average Maximum Head coach: Renan Dal Zotto 2nd: Blue Height: 182 198 209 Assistant coach: