Brucella Melitensis Brucella

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reportable Diseases and Conditions

KINGS COUNTY DEPARTMENT of PUBLIC HEALTH 330 CAMPUS DRIVE, HANFORD, CA 93230 REPORTABLE DISEASES AND CONDITIONS Title 17, California Code of Regulations, §2500, requires that known or suspected cases of any of the diseases or conditions listed below are to be reported to the local health jurisdiction within the specified time frame: REPORT IMMEDIATELY BY PHONE During Business Hours: (559) 852-2579 After Hours: (559) 852-2720 for Immediate Reportable Disease and Conditions Anthrax Escherichia coli: Shiga Toxin producing (STEC), Rabies (Specify Human or Animal) Botulism (Specify Infant, Foodborne, Wound, Other) including E. coli O157:H7 Scrombroid Fish Poisoning Brucellosis, Human Flavivirus Infection of Undetermined Species Shiga Toxin (Detected in Feces) Cholera Foodborne Disease (2 or More Cases) Smallpox (Variola) Ciguatera Fish Poisoning Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Tularemia, human Dengue Virus Infection Influenza, Novel Strains, Human Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (Crimean-Congo, Ebola, Diphtheria Measles (Rubeola) Lassa, and Marburg Viruses) Domonic Acid Poisoning (Amnesic Shellfish Meningococcal Infections Yellow Fever Poisoning) Novel Virus Infection with Pandemic Potential Zika Virus Infection Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning Plague (Specify Human or Animal) Immediately report the occurrence of any unusual disease OR outbreaks of any disease. REPORT BY PHONE, FAX, MAIL WITHIN ONE (1) WORKING DAY Phone: (559) 852-2579 Fax: (559) 589-0482 Mail: 330 Campus Drive, Hanford 93230 Conditions may also be reported electronically via the California -

Capture, Restraint and Transport Stress in Southern Chamois (Rupicapra Pyrenaica)

Capture,Capture, restraintrestraint andand transporttransport stressstress ininin SouthernSouthern chamoischamois ((RupicapraRupicapra pyrenaicapyrenaica)) ModulationModulation withwith acepromazineacepromazine andand evaluationevaluation usingusingusing physiologicalphysiologicalphysiological parametersparametersparameters JorgeJorgeJorge RamónRamónRamón LópezLópezLópez OlveraOlveraOlvera 200420042004 Capture, restraint and transport stress in Southern chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica) Modulation with acepromazine and evaluation using physiological parameters Jorge Ramón López Olvera Bellaterra 2004 Esta tesis doctoral fue realizada gracias a la financiación de la Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (proyecto CICYT AGF99- 0763-C02) y a una beca predoctoral de Formación de Investigadores de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, y contó con el apoyo del Departament de Medi Ambient de la Generalitat de Catalunya. Los Doctores SANTIAGO LAVÍN GONZÁLEZ e IGNASI MARCO SÁNCHEZ, Catedrático de Universidad y Profesor Titular del Área de Conocimiento de Medicina y Cirugía Animal de la Facultad de Veterinaria de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, respectivamente, CERTIFICAN: Que la memoria titulada ‘Capture, restraint and transport stress in Southern chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica). Modulation with acepromazine and evaluation using physiological parameters’, presentada por el licenciado Don JORGE R. LÓPEZ OLVERA para la obtención del grado de Doctor en Veterinaria, se ha realizado bajo nuestra dirección y, considerándola satisfactoriamente -

Compendium of Veterinary Standard Precautions for Zoonotic Disease Prevention in Veterinary Personnel

Compendium of Veterinary Standard Precautions for Zoonotic Disease Prevention in Veterinary Personnel National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians Veterinary Infection Control Committee 2010 Preface.............................................................................................................................................................. 1405 I. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................... 1405 A. OBJECTIVES...................................................................................................................................... 1405 B. BACKGROUND................................................................................................................................. 1405 C. CONSIDERATIONS.......................................................................................................................... 1405 II. ZOONOTIC DISEASE TRANSMISSION................................................................................................ 1406 A. SOURCE ............................................................................................................................................ 1406 B. HOST SUSCEPTIBILITY.................................................................................................................... 1406 C. ROUTES OF TRANSMISSION........................................................................................................... 1406 1. CONTACT TRANSMISSION......................................................................................................... -

Herd Health Protocols for Dromedary Camels (Camelus Dromedarius) at Mpala Ranch and Research Centre, Laikipia County, Kenya

Herd Health Protocols for Dromedary Camels (Camelus dromedarius) at Mpala Ranch and Research Centre, Laikipia County, Kenya September 23rd, 2012 Andrew Springer Browne, MVB Veterinary Public Health Program University of Missouri – Columbia, USA Sharon Deem, DVM, PhD, DACZM Institute for Conservation Medicine Saint Louis Zoo, St. Louis, MO, USA This guide was made to solidify husbandry and record protocols as well as give feasible advice for common health problems in camels at the Mpala Ranch and Research Centre. For thorough reviews of camel diseases and health, see “A Field Manual of Camel Diseases” by Kohler-Rollefson and “Medicine and Surgery of Camelids” by Fowler. Acknowledgments Many thanks to Margaret Kinnaird and Mike Littlewood for their patience and support during our visit. Thank you to Laura Budd and Sina Mahs for their incredible help and time dedicated to the project. Finally, a special thanks to S. Moso, Eputh, Abduraman, Adow, Abdulai, Ekomoel, and Ewoi for working and living with the camels every day. Asante sana. - Springer and Sharon ii Table of Contents Page Key Management Goals 1 Record Keeping 2 Electronic and Paper Records 3 Entering Data into Excel Database 4 Excel Database Legend 5 Husbandry 6 Calf Care 7 Maternal Rejection 8 Dam Care 9 Branding and Identification 10 Weight Estimates/Body Condition Scoring 11 Milking Schedule and Boma Rotation 12 Veterinary Care 13 Preventive Veterinary Health Care 14 Diagnostics 15 Abortion 16 Skin Wounds 17 Abscess Treatment 18 Mastitis 19 Eye Problems 20 Diseases of Special -

LIST of REPORTABLE COMMUNICABLE DISEASES in BC July 2009

LIST OF REPORTABLE COMMUNICABLE DISEASES IN BC July 2009 Schedule A: Reportable by all sources, including Laboratories Meningococcal Disease, All Invasive including “Primary Meningococcal Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Pneumonia” and “Primary Meningococcal Anthrax Conjunctivitis” Botulism Mumps Brucellosis Neonatal Group B Streptococcal Infection Chancroid Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP) Cholera Pertussis (Whooping Cough) Congenital Infections: Plague Toxoplasmosis Poliomyelitis Rubella Rabies Cytomegalovirus Reye Syndrome Herpes Simplex Rubella Varicella-Zoster Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Hepatitis B Virus Smallpox Listeriosis and any other congenital infection Streptococcus pneumoniae Infection, Invasive Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease Syphilis Cryptococcal infection Tetanus Cryptosporidiosis Transfusion Transmitted Infection Cyclospora infection Tuberculosis Diffuse Lamellar Keratitis Tularemia Diphtheria: Typhoid Fever and Paratyphoid Fever Cases Waterborne Illness Carriers All causes Encephalitis: West Nile Virus Infection Post-infectious Yellow Fever Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis Vaccine-related Viral Schedule B: Reportable by Laboratories only Foodborne illness: All causes All specific bacterial and viral stool pathogens: Gastroenteritis epidemic: (i) Bacterial: Bacterial Campylobacter Parasitic Salmonella Viral Shigella Genital Chlamydia Infection Yersinia Giardiasis (ii) Viral Gonorrhea – all sites Amoebiasis Group A Streptococcal Disease, Invasive Borrelia burgdorferi infection H5 and H7 strains of the -

Genital Brucella Suis Biovar 2 Infection of Wild Boar (Sus Scrofa) Hunted in Tuscany (Italy)

microorganisms Article Genital Brucella suis Biovar 2 Infection of Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) Hunted in Tuscany (Italy) Giovanni Cilia * , Filippo Fratini , Barbara Turchi, Marta Angelini, Domenico Cerri and Fabrizio Bertelloni Department of Veterinary Science, University of Pisa, Viale delle Piagge 2, 56124 Pisa, Italy; fi[email protected] (F.F.); [email protected] (B.T.); [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (F.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Brucellosis is a zoonosis caused by different Brucella species. Wild boar (Sus scrofa) could be infected by some species and represents an important reservoir, especially for B. suis biovar 2. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of Brucella spp. by serological and molecular assays in wild boar hunted in Tuscany (Italy) during two hunting seasons. From 287 animals, sera, lymph nodes, livers, spleens, and reproductive system organs were collected. Within sera, 16 (5.74%) were positive to both rose bengal test (RBT) and complement fixation test (CFT), with titres ranging from 1:4 to 1:16 (corresponding to 20 and 80 ICFTU/mL, respectively). Brucella spp. DNA was detected in four lymph nodes (1.40%), five epididymides (1.74%), and one fetus pool (2.22%). All positive PCR samples belonged to Brucella suis biovar 2. The results of this investigation confirmed that wild boar represents a host for B. suis biovar. 2 and plays an important role in the epidemiology of brucellosis in central Italy. Additionally, epididymis localization confirms the possible venereal transmission. Citation: Cilia, G.; Fratini, F.; Turchi, B.; Angelini, M.; Cerri, D.; Bertelloni, Keywords: Brucella suis biovar 2; wild boar; surveillance; epidemiology; reproductive system F. -

Hippotragus Equinus – Roan Antelope

Hippotragus equinus – Roan Antelope authorities as there may be no significant genetic differences between the two. Many of the Roan Antelope in South Africa are H. e. cottoni or equinus x cottoni (especially on private properties). Assessment Rationale This charismatic antelope exists at low density within the assessment region, occurring in savannah woodlands and grasslands. Currently (2013–2014), there are an observed 333 individuals (210–233 mature) existing on nine formally protected areas within the natural distribution range. Adding privately protected subpopulations and an Cliff & Suretha Dorse estimated 0.8–5% of individuals on wildlife ranches that may be considered wild and free-roaming, yields a total mature population of 218–294 individuals. Most private Regional Red List status (2016) Endangered subpopulations are intensively bred and/or kept in camps C2a(i)+D*†‡ to exclude predators and to facilitate healthcare. Field National Red List status (2004) Vulnerable D1 surveys are required to identify potentially eligible subpopulations that can be included in this assessment. Reasons for change Non-genuine: While there was an historical crash in Kruger National Park New information (KNP) of 90% between 1986 and 1993, the subpopulation Global Red List status (2008) Least Concern has since stabilised at c. 50 individuals. Overall, over the past three generations (1990–2015), based on available TOPS listing (NEMBA) Vulnerable data for nine formally protected areas, there has been a CITES listing None net population reduction of c. 23%, which indicates an ongoing decline but not as severe as the historical Endemic Edge of Range reduction. Further long-term data are needed to more *Watch-list Data †Watch-list Threat ‡Conservation Dependent accurately estimate the national population trend. -

Anaplasma Phagocytophilum and Babesia Species Of

pathogens Article Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia Species of Sympatric Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus), Fallow Deer (Dama dama), Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) and Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) in Germany Cornelia Silaghi 1,2,*, Julia Fröhlich 1, Hubert Reindl 3, Dietmar Hamel 4 and Steffen Rehbein 4 1 Institute of Comparative Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Leopoldstr. 5, 80802 Munich, Germany; [email protected] 2 Institute of Infectology, Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Südufer 10, 17493 Greifswald Insel Riems, Germany 3 Tierärztliche Fachpraxis für Kleintiere, Schießtrath 12, 92709 Moosbach, Germany; [email protected] 4 Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH, Kathrinenhof Research Center, Walchenseestr. 8-12, 83101 Rohrdorf, Germany; [email protected] (D.H.); steff[email protected] (S.R.) * Correspondence: cornelia.silaghi@fli.de; Tel.: +49-0-383-5171-172 Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 18 November 2020; Published: 20 November 2020 Abstract: (1) Background: Wild cervids play an important role in transmission cycles of tick-borne pathogens; however, investigations of tick-borne pathogens in sika deer in Germany are lacking. (2) Methods: Spleen tissue of 74 sympatric wild cervids (30 roe deer, 7 fallow deer, 22 sika deer, 15 red deer) and of 27 red deer from a farm from southeastern Germany were analyzed by molecular methods for the presence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia species. (3) Results: Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia DNA was demonstrated in 90.5% and 47.3% of the 74 combined wild cervids and 14.8% and 18.5% of the farmed deer, respectively. Twelve 16S rRNA variants of A. phagocytophilum were delineated. -

Environment-Dependent Variation in Gut Microbiota of an Oviparous Lizard (Calotes Versicolor)

animals Article Environment-Dependent Variation in Gut Microbiota of an Oviparous Lizard (Calotes versicolor) Lin Zhang 1,2,*,† , Fang Yang 3,†, Ning Li 4 and Buddhi Dayananda 5 1 School of Basic Medical Sciences, Hubei University of Chinese Medicine, Wuhan 430065, China 2 State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology, Institute of Microbial Technology, Shandong University, Qingdao 266237, China 3 School of Laboratory Medicine, Hubei University of Chinese Medicine, Wuhan 430065, China; [email protected] 4 College of Food Science, Nanjing Xiaozhuang University, Nanjing 211171, China; [email protected] 5 School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Simple Summary: The different gut sections potentially provide different habitats for gut microbiota. We found that Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria were the three primary phyla in gut micro- biota of C. versicolor. The relative abundance of dominant phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes exhibited an increasing trend from the small intestine to the large intestine, and there was a higher abun- dance of genus Bacteroides (Class: Bacteroidia), Coprobacillus and Eubacterium (Class: Erysipelotrichia), Parabacteroides (Family: Porphyromonadaceae) and Ruminococcus (Family: Lachnospiraceae), and Family Odoribacteraceae and Rikenellaceae in the hindgut, and some metabolic pathways were higher in the hindgut. Our results reveal the variations of gut microbiota composition and metabolic pathways in Citation: Zhang, L.; Yang, F.; Li, N.; different parts of the lizards’ intestine. Dayananda, B. Environment- Dependent Variation in Gut Abstract: Vertebrates maintain complex symbiotic relationships with microbiota living within their Microbiota of an Oviparous Lizard gastrointestinal tracts which reflects the ecological and evolutionary relationship between hosts and (Calotes versicolor). -

Veterinary Services Newsletter August 2017

August 2017 Veterinary Services Newsletter August 2017 Wildlife Health Laboratory Veterinary Services Staff NALHN Certification: The Wildlife Health Laboratory has been working towards joining the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NALHN) in order to have ac- cess to all CWD testing kits. The commercial test kits for CWD are now restricted, and Branch Supervisor/Wildlife only NALHN approved laboratories have access to all the kits that are currently availa- Veterinarian: Dr. Mary ble. To be considered for the program, our laboratory must meet the ISO 17025 stand- Wood ards of quality control that assure our laboratory is consistently and reliably producing Laboratory Supervisor: accurate results. In addition, our laboratory will be regularly inspected by APHIS Veter- Hank Edwards inary Services, and we will be required to complete annual competency tests. Although we have been meeting most of the ISO standards for several years, applying to the Senior Lab Scientist: NAHLN has encouraged us to tighten many of our procedures and quality control moni- Hally Killion toring. We hope to have the application submitted by the middle of August and we have our first APHIS inspection in September. Senior Lab Scientist: Jessica Jennings-Gaines Brucellosis Lab Assistant: New CWD area for elk: The Wildlife Health Laboratory confirmed the first case of Kylie Sinclair CWD in an elk from hunt area 48. This animal was captured in elk hunt area 33 as part of the elk movement study in the Bighorns to study Brucellosis. She was found dead in Wildlife Disease Specialist: hunt area 48, near the very southeastern corner of Washakie County. -

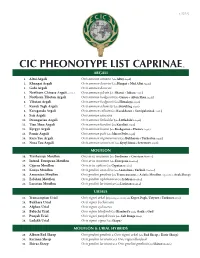

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Characterization of Environmental and Cultivable Antibiotic- Resistant Microbial Communities Associated with Wastewater Treatment

antibiotics Article Characterization of Environmental and Cultivable Antibiotic- Resistant Microbial Communities Associated with Wastewater Treatment Alicia Sorgen 1, James Johnson 2, Kevin Lambirth 2, Sandra M. Clinton 3 , Molly Redmond 1 , Anthony Fodor 2 and Cynthia Gibas 2,* 1 Department of Biological Sciences, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, NC 28223, USA; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (M.R.) 2 Department of Bioinformatics and Genomics, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, NC 28223, USA; [email protected] (J.J.); [email protected] (K.L.); [email protected] (A.F.) 3 Department of Geography & Earth Sciences, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, NC 28223, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-704-687-8378 Abstract: Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is a growing global concern, threatening human and environmental health, particularly among urban populations. Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are thought to be “hotspots” for antibiotic resistance dissemination. The conditions of WWTPs, in conjunction with the persistence of commonly used antibiotics, may favor the selection and transfer of resistance genes among bacterial populations. WWTPs provide an important ecological niche to examine the spread of antibiotic resistance. We used heterotrophic plate count methods to identify Citation: Sorgen, A.; Johnson, J.; phenotypically resistant cultivable portions of these bacterial communities and characterized the Lambirth, K.; Clinton,