Pearl Harbor: a Failure for Baseball? PUB DATE 76 NOTE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: a Comparison of Rose V

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 13 | Number 3 Article 6 1-1-1991 Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial Michael W. Klein Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael W. Klein, Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial, 13 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 551 (1991). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol13/iss3/6 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial by MICHAEL W. KLEIN* Table of Contents I. Baseball in 1919 vs. Baseball in 1989: What a Difference 70 Y ears M ake .............................................. 555 A. The Economic Status of Major League Baseball ....... 555 B. "In Trusts We Trust": A Historical Look at the Legal Status of Major League Baseball ...................... 557 C. The Reserve Clause .......................... 560 D. The Office and Powers of the Commissioner .......... 561 II. "You Bet": U.S. Gambling Laws in 1919 and 1989 ........ 565 III. Black Sox and Gold's Gym: The 1919 World Series and the Allegations Against Pete Rose ............................ -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs. Cleveland Indians Saturday, October 29, 2016 Game 4 - 7:08 P.M

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2016 GAME 4 - 7:08 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 4 Saturday, October 29th Wrigley Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 4 at Chicago: John Lackey (11-8, 3.35/0-0, 5.63) vs. Corey Kluber (18-9, 3.14/3-1, 0.74) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) SERIES AT 2-1 CUBS AT 1-2 This is the 87th time in World Series history that the Fall Classic has • This is the eighth time that the Cubs trail a best-of-seven stood at 2-1 after three games, and it is the 13th time in the last 17 Postseason series, 2-1. -

Jimmy Johnston Earns Amateur Golftitle

SPORTS AND FINANCIAL Base Ball, Racing Stocks and Bonds Golf and General Financial News l_ five Jhinttmi fKtaf Part s—lo Pages WASHINGTON, 13. C., SUNDAY MORNING, SEPTEMBER 8, 1929. Griffs Beat Chisox in Opener, 2—l: Jimmy Johnston Earns Amateur Golf Title VICTOR AND VANQUISHED IN NATIONAL AMATEUR GOLF TOURNAMENT ¦¦ '¦ * mm i 1 11—— 1 I ¦¦l. mm MARBERRY LICKS THOMAS 1 i PRIDE OF ST. PAUL WINS IN FLASHY MOUND TUSSLE | ....... OYER DR. WILLING, 4 AND 3 i '<l \ j u/ Fred Yields Hut Six Hits and Holds Foe Seoreless JT Makes Strong Finish After Ragged Play in Morn- Until Ninth—Nats Get Seven Safeties—Earn ing to Take Measure of Portland Opponent. W '' ' / T Executes - of One Run, Berg Hands Them Another. /. / 4- jr""'"" 1 \ \ Wonder Shot Out Ocean. / 5 - \ \ •' * 11 f _jl"nil" >.< •*, liL / / A \ BY GRAXTLAND RICE. BY JOHN B. KELLER. Thomas on MONTE, Calif., September 7.—The green, soft fairway of MARBERRY was just a trifle stronger than A1 Pebble Beach the a new amateur as White Sex A \ caught footfall of champion the pitching slab yesterday the Nationals and f this afternoon. His name is Harrison ( series of the year ( Jimmy) Johnston, the clashed in the opening tilt of their wind-up PBHKm DELpride of St. Paul, who after a game, up-hill battle all through charges scored a 2-to-l victory that FREDand as a result Johnson’s \ morning fought his way into victory the grim, hard- back of the fifth-place Tigers, the crowd wtik the round, over left them but half a game fighting Doc Willing of Portland, Ore., by the margin of 4 and 3. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Hugginsscottauction Feb13.Pdf

elcome to Huggins and Scott Auctions, the Nation's fastest grow- W ing Sports & Americana Auction House. With this catalog, we are presenting another extensive list of sports cards and memo- rabilia, plus an array of historically significant Americana items. We hope you enjoy this. V E RY IMPORTA N T: DUE TO SIZE CONSTRAINTS AND T H E COST FAC TOR IN THE PRINT VERSION OF MOST CATA LOGS, WE ARE UNABLE TO INCLUDE ALL PICTURES AND ELA B O- R ATE DESCRIPTIONS ON EV E RY SINGLE LOT IN THE AUCTION. HOW EVER, OUR WEBSITE HAS NO LIMITATIONS, SO W E H AVE ADDED MANY MORE PH OTOS AND A MUCH MORE ELA B O R ATE DESCRIPTION ON V I RT UA L LY EV E RY ITEM ON OUR WEBSITE. WELL WO RTH CHECKING OUT IF YOU ARE SERIOUS ABOUT A LOT ! WEBSITE: W W W. H U G G I N S A N D S C OTT. C O M Here's how we are running our February 7, 2013 to STEP 2. A way to check if your bid was accepted is to go auction: to “My Bid List”. If the item you bid on is listed there, you are in. You can now sort your bid list by which lots you BIDDING BEGINS: hold the current high bid for, and which lots you have been Monday Ja n u a ry 28, 2013 at 12:00pm Eastern Ti m e outbid on. IF YOU HAVE NOT PLACED A BID ON AN ITEM BEFORE 10:00 pm EST (on the night the Our auction was designed years ago and still remains geared item ends), YOU CANNOT BID ON THAT ITEM toward affordable vintage items for the serious collector. -

Defining the Role of Prior Knowledge and Vocabulary in Reading Comprehension: the Retiring of Number 41

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 329 919 CS 010 470 AUTHOR Stahl, Steven A.; And Others TITLE Defining the Role of Prior Knowledge and Vocabulary in Reading Comprehension: The Retiring of Number 41. Technical Report No. 526. INSTITUTION Bolt, Beranek and Newman, Inc., Cambridge, Mass.; Illinois Univ., Urbana. Center for the Study of Reading. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE Apr 91 CONTRACT G0087-C1001-90 NOTE 25p. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Baseball; Context Clues; Grade 10; High Schools; *Prior Learning; Protocol Analysis; *Reader Text Relationship; *Reading Comprehension; Reading Research; Reading Skills; Reading Strategies; *Recall (Psychology); Schemata (Cognition); Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS Illinois; New York (Long Island); Text Factors ABSTRACT Using a newspaper article about a ceremony marking the retirement of baseball player Tom Seaver's uniform number,a study examined: (1) the effects of knowledge of baseballin general and of the career of Tom Seaver in particular; and (2) the effects of knowledge of word meanings in general and of words used in the passage specifically on 10th graders' recall of different aspects of passage content. Subjects, 159 10th graders from Illinois and Long Island, read a target passage and then were assessedon baseball knowledge and vocabulary knowledge. Vocabulary knowledge tendedto affect the number of units recalled overall, whereas prior knowledge influenced which units were recalled. Prior topic knowledge influenced whether subjects produced a "gist" statement in their recall and how well they recalled numbers relevant to Seaver's career. High-knowledge subjects also tended to focus moreon information given about Seaver's career than did low-knowledge subjects. -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SUNDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2016 GAME 5 - 7:15 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 Gm. 4 - Sat., Oct. 29th CLE 7, CHI 2 Kluber Lackey — 41,706 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) Game 6 at Cleveland (if necessary): Josh Tomlin (13-9, 4.40/2-0/1.76) vs. Jake Arrieta (18-8, 3.10/1-1, 3.78) SERIES AT 3-1 CUBS AND INDIANS IN GAME 5 This marks the 47th time that the World Series stands at 3-1. Of • The Cubs are 6-7 all-time in Game 5 of a Postseason series, the previous 46 times, the team leading 3-1 has won the series 40 including 5-6 in a best-of-seven, while the Indians are 5-7 times (87.0%), and they have won Game 5 on 26 occasions (56.5%). -

Landis, Cobb, and the Baseball Hero Ethos, 1917 – 1947

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2020 Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 Lindsay John Bell Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bell, Lindsay John, "Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 18066. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/18066 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reconstructing baseball’s image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 by Lindsay John Bell A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Rural Agricultural Technology and Environmental History Program of Study Committee: Lawrence T. McDonnell, Major Professor James T. Andrews Bonar Hernández Kathleen Hilliard Amy Rutenberg The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this dissertation. The Graduate College will ensure this dissertation is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2020 Copyright © Lindsay John Bell, 2020. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

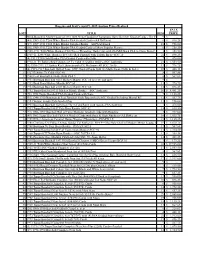

Prices Realized

SPRING 2014 PREMIER AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot# Title Final Price 1 C.1850'S LEMON PEEL STYLE BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $2,421.60 2 1880'S FIGURE EIGHT STYLE BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $576.00 3 C.1910 BASEBALL STITCHING MACHINE (NSM COLLECTION) $356.40 4 HONUS WAGNER SINGLE SIGNED BASEBALL W/ "FORMER PIRATE" NOTATION (NSM COLLECTION) $1,934.40 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO JUNE 30TH, 1909 FORBES FIELD (PITTSBURGH) OPENING GAME AND 5 DEDICATION CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $7,198.80 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO JUNE 30TH, 1910 FORBES FIELD OPENING GAME AND 1909 WORLD 6 CHAMPIONSHIP FLAG RAISING CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $1,065.60 1911 CHICAGO CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES (WHITE SOX VS. CUBS) PRESS TICKET AND SCORERS BADGE AND 1911 COMISKEY 7 PARK PASS (NSM COLLECTION) $290.40 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO MAY 16TH, 1912 FENWAY PARK (BOSTON) OPENING GAME AND DEDICATION 8 CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $10,766.40 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO APRIL 18TH, 1912 NAVIN FIELD (DETROIT) OPENING GAME AND DEDICATION 9 CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $1,837.20 ORIGINAL INVITATION TO AUGUST 18TH, 1915 BRAVES FIELD (BOSTON) OPENING GAME AND 1914 WORLD 10 CHAMPIONSHIP FLAG RAISING CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $939.60 LOT OF (12) 1909-1926 BASEBALL WRITERS ASSOCIATION (BBWAA) PRESS PASSES INCL. 6 SIGNED BY WILLIAM VEECK, 11 SR. (NSM COLLECTION) $580.80 12 C.1918 TY COBB AND HUGH JENNINGS DUAL SIGNED OAL (JOHNSON) BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $11,042.40 13 CY YOUNG SINGLE SIGNED BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $42,955.20 1929 CHICAGO CUBS MULTI-SIGNED BASEBALL INCL. ROGERS HORNSBY, HACK WILSON, AND KI KI CUYLER (NSM 14 COLLECTION) $528.00 PHILADELPHIA A'S GREATS; CONNIE MACK, CHIEF BENDER, EARNSHAW, EHMKE AND DYKES SIGNED OAL (HARRIDGE) 15 BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $853.20 16 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED 1948 FIRST EDITION COPY OF "THE BABE RUTH STORY" (NSM COLLECTION) $7,918.80 17 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $15,051.60 18 DIZZY DEAN SINGLE SIGNED BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $1,272.00 1944 & 1946 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ST. -

Yahoo! Sports Hits Home Run with Free Fantasy Baseball Yahoo! Users Can Now Create and Manage Their Own Pro Baseball Fantasy Team SANTA CLARA, Calif

Yahoo! Sports Hits Home Run With Free Fantasy Baseball Yahoo! Users Can Now Create and Manage Their Own Pro Baseball Fantasy Team SANTA CLARA, Calif. -- Feb. 23, 1999 -- Yahoo! users can now participate in America's favorite pastime online. Yahoo! Inc. (NASDAQ: YHOO), a leading global Internet media company, today introduced Yahoo! Sports Fantasy Baseball. Through Yahoo! Sports (http://sports.yahoo.com), a comprehensive resource for the latest sports news and information, baseball fans of all ages can now manage their own fantasy team using the real-life stats and results of today's big league stars such as Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, Ken Griffey, Jr., Roger Clemens, Randy Johnson, and Alex Rodriguez. Yahoo! Sports Fantasy Baseball gives game managers the opportunity to draft, play, trade, cut and bench real-life, pro-baseball players and compete for bragging rights with family, friends, co-workers and experienced fantasy team owners alike. Managers can also configure a scoring and stats system for their own private league. And unlike many competitive fantasy sports sites, which charge users a fee to join a league, make trades, and access fantasy statistics and scoring, Yahoo! Sports Fantasy Baseball is free to users. "Yahoo! Sports Fantasy Baseball provides team managers with a tremendous number of interactive tools and top-of-the-line features such as live online drafts, customizable statistical configurations, unlimited trades and transactions, and prompt customer serviceall free of charge," said Tonya Antonucci, senior producer, Yahoo! Sports. "And by delivering pitch-by-pitch game coverage, timely and accurate statistical data, results, and news, Yahoo! Sports Fantasy Baseball complements the fantasy game and allows users to participate in and get greater enjoyment from America's favorite pastime." Take Me Online to the Ballgame Yahoo! Sports Fantasy Baseball's comprehensive scoring system rewards players for every contribution their athletes make on the playing field from home runs and stolen bases to strikeouts and complete games. -

PDF of Apr 15 Results

Huggins and Scott's April 9, 2015 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Mind-Boggling Mother Lode of (16) 1888 N162 Goodwin Champions Harry Beecher Graded Cards - The First Football9 $ Card - in History! [reserve not met] 2 (45) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards—All Different 6 $ 896.25 3 (17) 1909-1911 T206 White Border Tougher Backs—All PSA Graded 16 $ 956.00 4 (10) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards of More Popular Players 6 $ 358.50 5 1909-1911 T206 White Borders Hal Chase (Throwing, Dark Cap) with Old Mill Back PSA 6--None Better! 3 $ 358.50 6 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Red Portrait) with Tolstoi Back--SGC 10 21 $ 896.25 7 (4) 1911 T205 Gold Border PSA Graded Cards with Cobb 7 $ 478.00 8 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #9 Ty Cobb (Checklist Offer)--SGC Authentic 21 $ 1,553.50 9 (4) 1910-1911 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets with #26 McGraw--All SGC 20-30 11 $ 776.75 10 (4) 1919-1927 Baseball Hall of Fame SGC Graded Cards with (2) Mathewson, Cobb & Sisler 10 $ 448.13 11 1927 Exhibits Ty Cobb SGC 40 8 $ 507.88 12 1948 Leaf Baseball #3 Babe Ruth PSA 2 8 $ 567.63 13 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle SGC 10 [reserve not met] 9 $ - 14 1952 Berk Ross Mickey Mantle SGC 60 11 $ 776.75 15 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle SGC 60 12 $ 896.25 16 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle Rookie—SGC Authentic 10 $ 4,481.25 17 (76) 1952 Topps Baseball PSA Graded Cards with Stars 7 $ 1,135.25 18 (95) 1948-1950 Bowman & Leaf Baseball Grab Bag with (8) SGC Graded Including Musial RC 12 $ 537.75 19 1954 Wilson Franks PSA-Graded Pair 11 $ 956.00 20 1955 Bowman Baseball Salesman Three-Card Panel with Aaron--PSA Authentic 7 $ 478.00 21 1963 Topps Baseball #537 Pete Rose Rookie SGC 82 15 $ 836.50 22 (23) 1906-1999 Baseball Hall of Fame Manager Graded Cards with Huggins 3 $ 717.00 23 (49) 1962 Topps Baseball PSA 6-8 Graded Cards with Stars & High Numbers--All Different 16 $ 1,015.75 24 1909 E90-1 American Caramel Honus Wagner (Throwing) - PSA FR 1.5 21 $ 1,135.25 25 1980 Charlotte O’s Police Orange Border Cal Ripken Jr. -

College Baseball Foundation January 30, 2008 Boyd, Thank You For

College Baseball Foundation P.O. Box 6507 Phone: 806-742-0301 x249 Lubbock TX 79493-6507 E-mail: [email protected] January 30, 2008 Boyd, Thank you for participating in the balloting for the College Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2008 Induction Class. We appreciate your willingness to help. In the voters packet you will find the official ballot, an example ballot, and the nominee biographies: 1. The official ballot is what you return to us. Please return to us no later than Mon- day, February 11. 2. The example ballot’s purpose is to demonstrate the balloting rules. Obviously the names on the example ballot are not the nominee names. That was done to prevent you from being biased by the rankings you see there. 3. Each nominee has a profile in the biography packet. Some are more detailed than others and reflect what we received from the institutions and/or obtained in our own research. The ballot instructions are somewhat detailed, so be sure to read the directions at the top of the official ballot. Use the example ballot as a reference. Please try to consider the nominees based on their collegiate careers. In many cases nominees have gone on to professional careers but keep the focus on his college career as a player and/or coach. The Veterans (pre-1947) nominees often lack biographical details relative to those in the post-1947 categories. In those cases, the criteria may take on a broader spectrum to include the impact they had on the game/history of college baseball, etc.