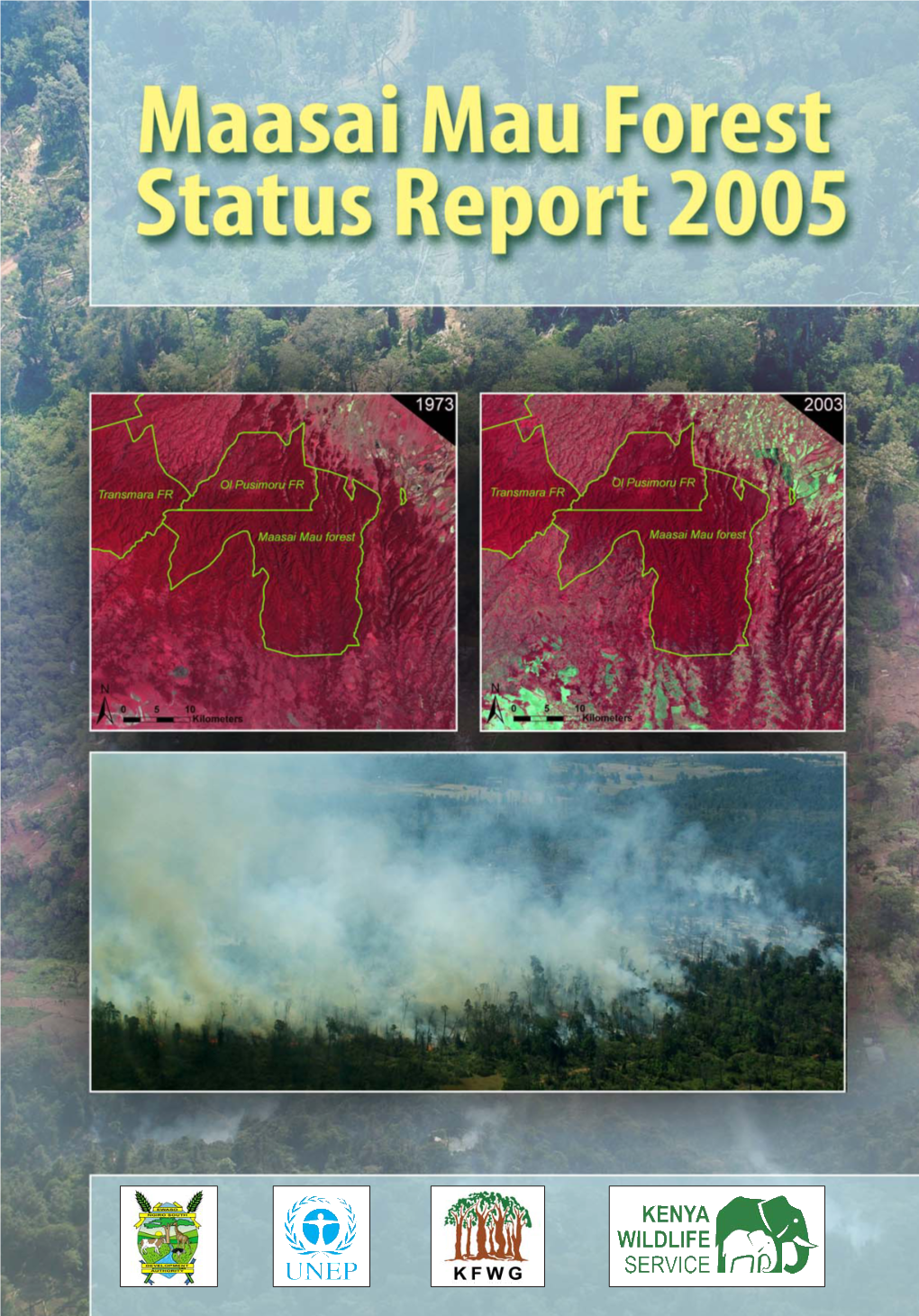

Maasai Mau Forest Status Report 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Electrical Resistivity Study of the Area Between Mt. Suswa and The

AN ELECTRICAL RESISTIVITY STUDY OF THE AREA BETWEEN MT. SUSWA AND * M THE OLKARIA GEOTHERMAL FIELD, KENYA STEPHEN ALUMASA ONACONACHA IIS TUF.sis n\sS rREEN e e n ACCEPTED m ^ e i t e d ^ fFOE HE DECREE of nd A COt'V M&vA7 BE PLACED IN 'TH& njivk.RSITY LIBRARY. A thesis submitted in accordance with the requirement for partial fulfillment of the V Degree of Master of Science DEPT. OF GEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 1989 DECLARATION jhis is my original work and has not b e e n submitted for a degree in any other university S . A . ONACHA The thesis has been submitted for examination with our Knowledge as University Supervisors: /] Mr. E. DINDI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my supervisors Dr. M.P. Tole and Mr. E. Dindi for their invaluable help and advice during the course of ray studies. I am grateful to the staff of the Ministry of Energy especially Mr. Kinyariro and Mr. Kilele for their tremendous help during the data acquisition. I also wish to express my appreciation of the University of Nairobi for their MSc Scholarship during my study. I am grateful to the British Council for their fellowship that enabled me to carry out data analysis at the University of Edinburgh. A ^ Finally, I wish to thank the members of my family for their love and understanding during my studies. ABSTRACT The D. C. electrical resistivity study of Suswa-Olkaria region was carried out from July 1987 to November, 1988. The main objective was to evaluate the sub-surface geoelectric structure with a view to determining layers that might be associated with geothermal fluid migrations. -

Maps, Power, and the Destruction of the Mau Forest in Kenya

Science & Technology Maps, Power, and the Destruction of the Mau Forest in Kenya Jacqueline M. Klopp and Job Kipkosgei Sang Tropical forests, which provide rich resources and criti- Jacqueline Klopp is 1 an assistant professor cal eco-services, are under severe stress. Some theories of international and regarding the causes of this stress emphasize “irreducible public affairs at the complexity,”2 while others point to specific factors, such School of International and Public Affairs at as population pressures or human encroachment through Columbia University. 3 “shifting cultivation.” Deforestation is indeed complex, Dr. Klopp’s research in part because it is linked not only to economic and social focuses on the intersec- tion of development, dynamics at both global and local levels, but also to questions democratization, vio- 4 of power and politics. Nowhere is this more evident than in lence, and corruption. the ongoing struggle over the Mau Forest in Kenya. Spanning 900 km2, the Mau forest is a complex of six- teen contiguous forests and six separated satellite forests. Together, they form a single ecosystem and make up the largest remaining indigenous forest in East Africa. While less is known about this forest than many other East African forests, the Mau forests complex is immensely important, as it serves as a catchment for rivers west of the Great Rift Valley. These rivers in turn feed major lakes in the region, including Lake Nakuru and the trans-boundary lakes of Lake Victoria in the Nile River Basin, Lake Turkana in Kenya and Ethiopia, and Lake Natron in Tanzania and Kenya. -

Kenyan Stone Age: the Louis Leakey Collection

World Archaeology at the Pitt Rivers Museum: A Characterization edited by Dan Hicks and Alice Stevenson, Archaeopress 2013, pages 35-21 3 Kenyan Stone Age: the Louis Leakey Collection Ceri Shipton Access 3.1 Introduction Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey is considered to be the founding father of palaeoanthropology, and his donation of some 6,747 artefacts from several Kenyan sites to the Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM) make his one of the largest collections in the Museum. Leakey was passionate aboutopen human evolution and Africa, and was able to prove that the deep roots of human ancestry lay in his native east Africa. At Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania he excavated an extraordinary sequence of Pleistocene human evolution, discovering several hominin species and naming the earliest known human culture: the Oldowan. At Olorgesailie, Kenya, he excavated an Acheulean site that is still influential in our understanding of Lower Pleistocene human behaviour. On Rusinga Island in Lake Victoria, Kenya he found the Miocene ape ancestor Proconsul. He obtained funding to establish three of the most influential primatologists in their field, dubbed Leakey’s ‘ape women’; Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Birute Galdikas, who pioneered the study of chimpanzee, gorilla and orangutan behaviour respectively. His second wife Mary Leakey, whom he first hired as an artefact illustrator, went on to be a great researcher in her own right, surpassing Louis’ work with her own excavations at Olduvai Gorge. Mary and Louis’ son Richard followed his parents’ career path initially, discovering many of the most important hominin fossils including KNM WT 15000 (the Nariokotome boy, a near complete Homo ergaster skeleton), KNM WT 17000 (the type specimen for Paranthropus aethiopicus), and KNM ER 1470 (the type specimen for Homo rudolfensis with an extremely well preserved Archaeopressendocranium). -

Layout Kenya Report.Indd

Nowhere to go Forced evictions in Mau Forest, Kenya Briefing Paper, April 2007 Nowhere to go Forced Evictions in Mau Forest, Kenya Briefing Paper, April 2007 Amnesty International Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions Kenya Land Alliance Hakijamii Trust Kenya National Commission on Human Rights Contents 1. Introduction 7 2. Forced evictions in forest areas 8 2.1 Forced Evictions in Maasai Mau 9 2.2 Forced Evictions in Sururu 10 2.3 Resettlement 11 3. Kenya’s legal framework for the protection against forced evictions 13 3.2 National law 14 4. Environment, land-grabbing and human rights 16 4.1 Protecting the forests 16 4.2 Land-grabbing and title deeds 16 4.3 Human rights 19 5. Conclusions 20 6. Recommendations 21 “Where I live now is unfit for human habitation. People who had relatives when they were evicted are ok, but others are living in temporary structures by the side of the road. They are like poultry houses. Children have dropped out of school and youth have gone astray. My husband is gone, and my daughter has gone into prostitution.” Victim of evictions in Mau Forest Complex 1. Introduction Between 2004 and 2006, a massive programme In October 2006, a coalition of national and of evictions has been carried out in forest areas of international human rights organisations Kenya. Houses, schools and health centres have including Amnesty International, the Centre on been destroyed, and many have been rendered Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE), Hakijammi homeless. Estimates indicate that in six forests and the Kenya Land Alliance undertook a fact alone, more than a hundred thousand persons finding mission to two areas of the Mau Forest were forcibly evicted between July 2004 and June Complex to investigate the extent of forced 2006.1 Evictions in a number of forest areas are evictions and other related human rights reportedly continuing and humanitarian groups violations. -

The Case of Mau Forest, Kenya

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal October 2015 /SPECIAL/ edition Vol.1 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 BIODIVERSITY, LOCAL RESOURCE, NATIONAL HERITAGE, REGIONAL CONCERN, AND GLOBAL IMPACT: THE CASE OF MAU FOREST, KENYA Prof Marion Mutugi Deputy Vice Chancellor, University of Kabianga, Kericho, Kenya Dr Winfred Kiiru Director, Conservation Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya Abstract The Mau Forest situated in western Kenya is is the largest remaining near continuous block of indigenous forest in East Africa. It is a biodiversity haven with a wide range of fauna and flora some of which are endangered. The Mau is important as a water tower feeding rivers and lakes thus supporting livelihoods of millions of people in Kenya and the region. Over the last 20 years an estimated 2000 Km2 of forest was destroyed in the Mau resulting in environmental, social and economic loss. As a major water tower, the impact of this loss is evident lowered water levels in the rivers that emanate from this forest and increased temperatures. In addition are economic losses in agriculture, tourism and energy sectors that affect the livelihoods of people not just in areas adjacent to the Mau but also in neighbouring countires. The unobstructed destruction of the Mau forest continues to deprive the country of a national heritage and is of regional and global concern. Attempts to rehabilitate the Mau have had limited success and they require multidisciplinary local and international support. Keywords: Biodiversity, genetic diversity, forest, ecosystem, natural resources Introduction Biodiversity is Africa’s richest asset with knowledge of medicinal, agricultural and other properties of the biological resources developed over centuries harbored by the local people. -

Country Update Report for Kenya 2010–2015

Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2015 Melbourne, Australia, 19-25 April 2015 Country Update Report for Kenya 2010-2014 Peter Omenda and Silas Simiyu Geothermal Development Company, P. O. Box 100746, Nairobi 00101, Kenya [email protected] Keywords: Geothermal, Kenya rift, Country update. ABSTRACT Geothermal resources in Kenya have been under development since 1950’s and the current installed capacity stands at 573 MWe against total potential of about 10,000 MWe. All the high temperature prospects are located within the Kenya Rift Valley where they are closely associated with Quaternary volcanoes. Olkaria geothermal field is so far the largest producing site with current installed capacity of 573 MWe from five power plants owned by Kenya Electricity Generating Company (KenGen) (463 MWe) and Orpower4 (110 MWe). 10 MWt is being utilized to heat greenhouses and fumigate soils at the Oserian flower farm. The Oserian flower farm also has 4 MWe installed for own use. Power generation at the Eburru geothermal field stands at 2.5 MWe from a pilot plant. Development of geothermal resources in Kenya is currently being fast tracked with 280 MWe commissioned in September and October 2014. Production drilling for the additional 560 MWe power plants to be developed under PPP arrangement between KenGen and private sector is ongoing. The Geothermal Development Company (GDC) is currently undertaking production drilling at the Menengai geothermal field for 105 MWe power developments to be commissioned in 2015. Detailed exploration has been undertaken in Suswa, Longonot, Baringo, Korosi, Paka and Silali geothermal prospects and exploration drilling is expected to commence in year 2015 in Baringo – Silali geothermal area. -

Kenya's Indigenous Forests

IUCN Forest Conservation Programme Kenya's Indigenous Forests Status, Management and Conservation Peter Wass Editor E !i,)j"\|:'\': A'e'±'i,?ai) £ ..X S W..T^ M "t "' mm~:P dmV ../' CEA IUCNThe World Conservation Union Kenya's Indigenous Forests Status, Management and Conservation IUCN — THE WORLD CONSERVATION UNION Founded in 1948, The World Conservation Union brings together States, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a u nique world partnership : over 800 members in all, spread across some 130 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is eq uitable and ecologically sustainable. A central secretariat coordinates the IUCN Programme and serves the Union membership, representing their views on the world stage and providing them with the strategies, servi- ces, scientific knowledge and technical support they need to achieve their goals. Through its six Com- missions, IUCN draws together over 6000 expert volunteers in project teams and action groups, focu- sing in particular on species and biodiversity conservation and the management of habitats and natural resources. The Union has helped many countries to prepare National ConseNation Strategies, and demons- trates the application of its knowledge through the field projects it supervises. Operations are increa- singly decentralized and are carried forward by an expanding network of regional and country offices, located principally in developing countries. The World Conservation Union builds on the strengths of its members, networks and partners to enhance their capacity and to support global alliances to safeguard natural resources at local, regional and global levels. -

Geophysical and Hydrogeological Investigation Report

GEOPHYSICAL AND HYDROGEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION REPORT St Peters Catholic Church- Upendo in Kangawa, P.O. Box 230, Molo. Through The Catholic Diocese of Nakuru, through the Nakuru Defluoridation Co. Ltd P.O. Box 2943 - 20100 Nakuru Plot LR No.; …………………… Kangawa-Upendo Village, Kangawa Sub-Location, Kuresoi North Location, Mau Summit Division, Molo Sub-County, Nakuru County. Topo Sheet No.; 118/2 CONSULTANT: Samuel Munyiri, BSc, MSc. (Hons) R. Geol. (Registered Hydrogeologist; Licence No. WD/WP/254) P.O. Box 798-10101, Karatina. Cell-phone: 0723 623 766 E-mail: [email protected] Signed:_________________________________ Date:___________________________________ June, 2018 Hydrogeological and Geophysical Report St. Peters Upendo Catholic Church EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction This report presents the findings of a geophysical and hydro-geological assessment carried out for St Peters Upendo Catholic Church-Kangawa on their 2 Acre parcel of land located in Kangawa Village, Kangawa Sub-Location, Kuresoi North Location and Mau Summit Division in Molo Sub- County of Nakuru County. The farm is located off the Molo-Londiani tarmac road section – at a distance of about 8km from Molo Town on the right hand side of this main road. The land can be accessed at the Kangawa Primary School junction and is about 1.8km west of this junction along a dry weather road. Water Demand and Use Kangawa-Upendo community is not served by any source of portable piped water, which would imply a near absence water supply on the client’s land. Apart from private boreholes and shallow wells in the area, there is no other feasible water supply. The community therefore relies on shallow wells, which have contaminated water due to percolation of fecal material from pit latrines. -

Forestry Carbon Sequestration and Trading: a Case of Mau Forest

FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Department of Industrial Development, IT and Land Management Forestry carbon sequestration and trading: a case of Mau Forest Complex in Kenya Forest Change detection and carbon trading Kevine Okoth Otieno 2016 Student thesis, Master degree (one year), 15 HE Geomatics Master Programme in Geomatics Degree Project in Geomatics & Land Management (DPGEOLM) Supervisor: Anders Brandt Examiner: Markku Pyykönen & Ding Ma Abstract The global temperature is at an all-time high, the polar ice is melting, the sea levels are rising and the associated disasters are a time bomb. These variations in temperature are thought to trace roots to anthropogenic sources. In order to mitigate these changes and slow down the rate of warming, several efforts have been made locally and internationally. One of the agreed up-on way to do this is by using forests as reservoirs for carbon since carbon is one of those greenhouses gasses responsible for the warming. Mau forest, in Kenya, is one of those ecosystems where degradation has happened tremendously, though still viewed as a potential site for reclamation. Using GIS and remote sensing analysis of Landsat images, the study sought to compare various change detection techniques, find the amount of biomass lost or gained in the forest and the possible income accrued in case the forest is placed under the Kyoto protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Various vegetation ratios were used in the study ranging from NDVI, NDII to RSR. The results obtained from these ratios were not quite convincing as setting threshold for the ratios to separate dense forest from other forms of vegetation was not straightforward. -

Geology Natvasha Area

Report No. 55 GOVERNMENT OF KENYA* MINISTRY OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF KENYA GEOLOGY OF THE NATVASHA AREA EXPLANATION OF DEGREE SHEET 43 S.W. (with coloured geological map) by A. O. THOMPSON M.Sc. and R. G. DODSON M.Sc. Geologists Fifteen Shillings - 1963 Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued information available for consultation, following Fair Use Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the materials within the archives where the identification of the Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the originators. For questions please contact soil.isric(a>wur.nl indicating the item reference number concerned. ISRIC LIBRARY ü£. 6Va^ [ GEOLOGY Wageningen, The Netherlands | OF THE EXPLANATION OF DEGREE SHEET 43 S.W. (with coloured geological map) by A. O. THOMPSON M.Sc. and R. G. DODSON M.Sc. Geologists FOREWORD Previous to the undertaking of modern geological surveys the Naivasha area, in the south-central part of Kenya Rift Valley, was probably the best known part of the Colony from the geological point of view. This resulted partly from ease of access, as from the earliest days the area was crossed by commonly used routes of com munication, and partly from the presence of lakes, which in Pleistocene times were much larger and made the country an ideal habitat for Prehistoric Man and animals that have left their traces behind them in the beds that were then deposited. -

Simon Mang'erere Onywere

Onywere Summer School 2005 Morphological Structure and the Anthropogenic Dynamics in the Lake Naivasha Drainage Basin and its Implications to Water Flows Simon Mang’erere Onywere Department of Environmental Planning and Management, Kenyatta University P.O. Box 43844 Nairobi 00100, Kenya E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Throughout its length, the Kenyan Rift Valley is characterized by Quaternary volcanoes. At Lake Naivasha drainage basin, the Eburru (2830m) and Olkaria (2434m) volcanic complexes and Kipipiri (3349m), Il Kinangop (3906m) and Longonot (2777m) volcanoes mark the terrain. Remote sensing data and field survey were used to make morphostructural maps and to determine the structural control and the land use impacts on the drainage systems in the basin. Lake Naivasha is located at the southern part of the highest part of Kenya’s Rift Valley floor in a trough marked to the south and north by Quaternary normal faults and extensional fractures striking in a N18°W direction. The structure of the rift floor influences the axial geometry and the surface process. Simiyu and Keller (2001) interpret the rift floor structure as due to thickening related to the pre-rift crustal type and modification by magmatic processes. The rift marginal escarpments of Sattima and Mau form the main watershed areas. From the marginal escarpments the Rift Valley is formed by a series of down-stepped fault scraps. These influence the nature of the soils and the rainfall regime. The drainage is also influenced by the fault trends. At the Malewa fault line for example the drainage is south-easterly influenced by the trend of the Malewa fault line (Thompson and Dodson, 1963). -

Lectures on Geothermal in Kenya and Africa

GEOTHERMAL TRAINING PROGRAMME Reports 2005 Orkustofnun, Grensásvegur 9, Number 4 IS-108 Reykjavík, Iceland LECTURES ON GEOTHERMAL IN KENYA AND AFRICA Martin N. Mwangi (lecturer and co-ordinator) Kenya Electricity Generating Co., Ltd. - KenGen Olkaria Geothermal Project P.O. Box 785 Naivasha KENYA Lectures on geothermal energy given in September 2005 United Nations University, Geothermal Training Programme Reykjavík, Iceland Published in April 2006 ISBN - 9979-68-187-X Mwangi ii Lectures PREFACE Kenya is the leading African country in geothermal exploration and development. Electricity generation from geothermal started in 1981 at the Olkaria I power station. In 2005 the installed generation capacity is 129 MWe, and the electricity production constitutes 11% of the total electricity production in the country. There is a plan to increase the generation capacity by 576 MWe by 2026. Behind all this is the Kenya Electricity Generating Company Ltd. (KenGen) and their very able staff. The UNU Visiting Lecturer 2005 was Mr. Martin N. Mwangi, Chief Manager of KenGen´s Olkaria Geothermal Project, who is one of the leading geothermal experts of Africa. He received training in geophysical exploration as UNU Fellow at the UNU-GTP in 1982. With him came a geochemist (Mr. Zaccheus Muna) and a drilling engineer (Mr. Joseph Ng´ang´a). Including the trio from that vintage year in geothermal studies, a total of 37 Kenyans have completed the six months specialized training at the UNU-GTP. Of these, 33 have come from KenGen. Martin gave an excellent summary of geothermal work in Kenya. In the first lecture (co-authored by Mrs.