Parliamentary Monitor 2019: Snapshot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOUSE of COMMONS Exiting the European Union Committee

HOUSE OF COMMONS Exiting the European Union Committee Oral evidence: The progress of the UK’s negotiations on EU withdrawal, HC 372 Monday 3 September 2018, Brussels Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 4 September 2018. Members present: Hilary Benn (Chair); Sir Christopher Chope; Stephen Crabb; Richard Graham; Peter Grant; Andrea Jenkyns; Stephen Kinnock; Jeremy Lefroy; Mr Pat McFadden; Seema Malhotra; Mr Jacob Rees-Mogg; Emma Reynolds; Stephen Timms; Mr John Whittingdale. Questions 2537 - 2563 Witnesses I: Michel Barnier, Chief Negotiator, European Commission, and Sabine Weyand, Deputy Chief Negotiator, European Commission. Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Michel Barnier and Sabine Weyand. Michel Barnier: Welcome once again. You are always welcome. Q2537 Chair: Michel, can I reciprocate on behalf of the Committee? It is very good to see you again. Can I begin by apologising that we had to let you down on the previous date when we were due to meet? We had certain important votes in Parliament that necessitated our attendance. Secondly, can I thank you very much for honouring the commitment you made to us the first time we met, that you would give evidence to the Committee on the record? Because as you are aware, today’s session is being recorded and will be published as an evidence session, so it is a slightly different format from our previous discussions. I understand entirely that you will want to check the English translation of what you said before the minutes are published and we realise that will take— Michel Barnier: Just to check that nothing is lost in translation. -

Training Session

information sheet Information sheets provide general information only, accurate as at the date of the information sheet. Law, policy and practice may change over time. ILPA members listed in the directory at www.ilpa.org.uk provide legal advice on individual cases. ILPA does not do so. The ILPA information service is funded by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. An archive of information sheets is available at www.ilpa.org.uk/infoservice.html Steve Symonds ILPA Legal Officer 020-7490 1553 [email protected] Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association www.ilpa.org.uk 020-7251 8383 (t) 020-7251 8384 (f) Legal Aid Bill 3 – Update 15th August 2011 This information sheet provides an update on the progress of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Bill since the June 2011 information sheets “Legal Aid Bill” and “Legal Aid Bill 2”. More information on the Bill as it affects children is available from the “Legal Aid Bill 4 – Children” information sheet. This information sheet first explains how to follow progress of the Bill. It then provides an update on the Bill’s progress to date and information about an important concession concerning domestic violence. Following progress of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Bill For those who want to follow the Bill’s progress more closely, the Bill has a page on the Parliament website: http://services.parliament.uk/bills/2010-11/legalaidsentencingandpunishmentofoffenders.html From this page it is possible to keep up to date on all the debates during the Bill’s progress through both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. -

Government Response to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee Report HC 109-1 of Session 2013-14 Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons

Government Response to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee Report HC 109-1 of Session 2013-14 Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty July 2014 Cm 8914 Government Response to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee Report HC 109-1 of Session 2013-14 Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty July 2014 Cm 8914 © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v.2. To view this licence visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2/ or email [email protected] Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. Print ISBN 9781474109796 Web ISBN 9781474109802 Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. ID P002659226 42260 07/14 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Government Response to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee 24th Report HC 109-1 of Session 2013-14, Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons The Government welcomes the European Scrutiny Committee’s Inquiry into Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons and the detailed consideration the Committee has given this important issue. -

Congressional Record—House H2019

May 15, 2020 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H2019 The SPEAKER pro tempore. The Burchett Hollingsworth Rice (SC) b 1246 question is on the resolution. Burgess Hudson Riggleman Byrne Huizenga Roby AFTER RECESS The question was taken; and the Calvert Hurd (TX) Rodgers (WA) Speaker pro tempore announced that Carter (GA) Jayapal Roe, David P. The recess having expired, the House the ayes appeared to have it. Chabot Johnson (LA) Rogers (AL) was called to order by the Speaker pro Cheney Johnson (OH) Mr. WOODALL. Madam Speaker, on Rogers (KY) tempore (Mr. CUELLAR) at 12 o’clock Cline Johnson (SD) Rose, John W. and 46 minutes p.m. that I demand the yeas and nays. Cloud Jordan Rouzer The yeas and nays were ordered. Cole Joyce (OH) Roy f Collins (GA) Joyce (PA) Rutherford The vote was taken by electronic de- Comer Katko AUTHORIZING REMOTE VOTING BY Scalise vice, and there were—yeas 207, nays Conaway Keller Schweikert PROXY AND PROVIDING FOR OF- Cook Kelly (MS) 199, not voting 24, as follows: Scott, Austin Crawford Kelly (PA) FICIAL REMOTE COMMITTEE [Roll No. 106] Crenshaw Khanna Sensenbrenner PROCEEDINGS DURING A PUBLIC YEAS—207 Curtis King (IA) Simpson HEALTH EMERGENCY DUE TO A Davidson (OH) King (NY) Smith (MO) Adams Gabbard Norcross NOVEL CORONAVIRUS Davis, Rodney Kinzinger Smith (NE) Aguilar Gallego O’Halleran Diaz-Balart Kustoff (TN) Smith (NJ) Allred Garamendi Mr. MCGOVERN. Mr. Speaker, pursu- Pallone Duncan LaHood Smucker Barraga´ n Garcia (TX) ant to House Resolution 967, I call up Panetta Dunn LaMalfa Spanberger Bass Golden Pappas Emmer Lamb Spano the resolution (H. -

Patient Health Records: Access, Sharing and Confidentiality

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07103, 14 April 2020 Patient health records: By Elizabeth Parkin, Philip access, sharing and Loft confidentiality Inside: 1. Accessing and sharing patient health records 2. Sharing confidential patient information 3. Electronic health records 4. NHS data and cyber security 5. Patient Data, Apps and Artificial Intelligence (AI) 6. Cross-border data sharing after Brexit www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 07103, 14 April 2020 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Accessing and sharing patient health records 4 1.1 Charges to access records 5 1.2 Limiting access to health records 6 1.3 Parental access to child health records 6 1.4 Access to deceased patients’ health records 7 2. Sharing confidential patient information 9 2.1 Patient confidentiality and Covid-19 9 2.2 NHS Constitution and policy background 13 2.3 NHS Digital guidance on confidentiality 14 2.4 National Data Guardian for health and care 14 Caldicott principles 15 2.5 National Data Guardian for health and care: priorities for 2019/20 16 2.6 National data opt-out programme 17 2.7 Legal and statutory disclosures of information 18 2.8 Disclosure of NHS data to the Home Office 19 2.9 Public interest disclosures of patient information 20 2.10 Deceased patients 21 2.11 Assessment of capacity to give or withhold consent 23 2.12 Private companies contracted to provide NHS services 24 3. Electronic health records 25 3.1 NHS ‘paper-free’ by 2023 25 3.2 Summary Care Records 27 4. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Wednesday Volume 630 25 October 2017 No. 40 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 25 October 2017 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2017 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 281 25 OCTOBER 2017 282 Scotland, at around 35%, many do not have access to House of Commons the internet and 51% are not IT literate; yet the Government are still closing three jobcentres, one of which serves Wednesday 25 October 2017 three homeless shelters. What assessment has the Minister made of the impact of closures on service users, many The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock of whom rely on face-to-face interaction with jobcentre staff? PRAYERS Damian Hinds: We did of course make an assessment [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] of the effect of the changes. Where the changes would involve people having to travel more than 3 miles or 20 minutes by public transport, we had a public Oral Answers to Questions consultation. [Interruption.] In one case, we changed the plan in the light of the consultation, as the hon. Member for Glasgow South (Stewart Malcolm McDonald) SCOTLAND well knows. We think it is right to move to larger jobcentres in which we can do more. They are better The Secretary of State was asked— equipped and have computers to ensure that that facility Jobcentre Closures is there, and there are specialists in the jobcentre who can help people with the computers and get through the 1. -

General Election 2019: Mps in Wales

Etholiad Cyffredinol 2019: Aelodau Seneddol yng Nghymru General Election 2019: MPs in Wales 1 Plaid Cymru (4) 5 6 Hywel Williams 2 Arfon 7 Liz Saville Roberts 2 10 Dwyfor Meirionnydd 3 4 Ben Lake 8 12 Ceredigion Jonathan Edwards 14 Dwyrain Caerfyrddin a Dinefwr / Carmarthen East and Dinefwr 9 10 Ceidwadwyr / Conservatives (14) Virginia Crosbie Fay Jones 1 Ynys Môn 13 Brycheiniog a Sir Faesyfed / Brecon and Radnorshire Robin Millar 3 Aberconwy Stephen Crabb 15 11 Preseli Sir Benfro / Preseli Pembrokeshire David Jones 4 Gorllewin Clwyd / Clwyd West Simon Hart 16 Gorllewin Caerfyrddin a De Sir Benfro / James Davies Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire 5 Dyffryn Clwyd / Vale of Clwyd David Davies Rob Roberts 25 6 Mynwy / Monmouth Delyn Jamie Wallis Sarah Atherton 33 8 Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Bridgend Wrecsam / Wrexham Alun Cairns 34 Simon Baynes Bro Morgannwg / Vale of Glamorgan 9 12 De Clwyd / Clwyd South 13 Craig Williams 11 Sir Drefaldwyn / Montgomeryshire 14 15 16 25 24 17 23 21 22 26 18 20 30 27 19 32 28 31 29 39 40 36 33 Llafur / Labour (22) 35 37 Mark Tami 38 7 34 Alyn & Deeside / Alun a Glannau Dyfrdwy Nia Griffith Gerald Jones 17 23 Llanelli Merthyr Tudful a Rhymni / Merthyr Tydfil & Rhymney Tonia Antoniazzi Nick Smith Chris Bryant 18 24 30 Gwyr / Gower Blaenau Gwent Rhondda Geraint Davies Nick Thomas-Symonds Chris Elmore Jo Stevens 19 26 31 37 Gorllewin Abertawe / Swansea West Tor-faen / Torfaen Ogwr / Ogmore Canol Caerdydd / Cardiff Central Carolyn Harris Chris Evans Stephen Kinnock Stephen Doughty 20 27 32 38 Dwyrain Abertawe / -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Sir Christopher Chope Mr Peter Bone Mr William Wragg Dr Julian Lewis Richard Drax Henry Smith Line 3, Leave out from “Until” to End and Insert “Monday 22 February”

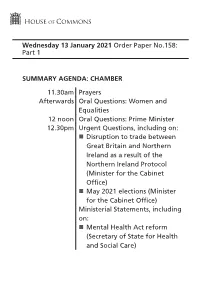

Wednesday 13 January 2021 Order Paper No.158: Part 1 SUMMARY AGENDA: CHAMBER 11.30am Prayers Afterwards Oral Questions: Women and Equalities 12 noon Oral Questions: Prime Minister 12.30pm Urgent Questions, including on: Disruption to trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a result of the Northern Ireland Protocol (Minister for the Cabinet Office) May 2021 elections (Minister for the Cabinet Office) Ministerial Statements, including on: Mental Health Act reform (Secretary of State for Health and Social Care) 2 Wednesday 13 January 2021 OP No.158: Part 1 Up to 20 Ten Minute Rule Motion: Covid- minutes 19 Financial Assistance (Gaps in Support) (Tracy Brabin) Until 7.00pm Financial Services Bill: Remaining Stages Until any hour* Business of the House (Today) (Motion) (*if the Business of the House Motion is agreed to) Up to one Sittings in Westminster Hall hour from the (Suspension) (No. 2) (Motion) commencement Business of the House (Private of proceedings Members’ Bills) (No. 9) (Motion) on the Business of the House (**if the Business of the House (Today) (Today) (Motion) is agreed to) Motion** No debate Statutory Instrument (Motion for approval) No debate Presentation of Public Petitions Wednesday 13 January 2021 OP No.158: Part 1 3 Until 7.30pm or Adjournment Debate: Support for half an hour for small business during the covid-19 outbreak (Christine Jardine) WESTMINSTER HALL 9.30am Support for pupils’ education during school closures 11.00am Discharges into rivers (The sitting will be suspended from 11.30am to 2.30pm.) 2.30pm Online anonymity 4.00pm Desecration of war memorials 4.30pm The political situation in Kashmir 4 Wednesday 13 January 2021 OP No.158: Part 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS PART 1: BUSINESS TODAY 5 Chamber 16 Westminster Hall 18 Written Statements 19 Committees Meeting Today 28 Announcements 33 Further Information PART 2: FUTURE BUSINESS 38 A. -

Background, Brexit, and Relations with the United States

The United Kingdom: Background, Brexit, and Relations with the United States Updated April 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33105 SUMMARY RL33105 The United Kingdom: Background, Brexit, and April 16, 2021 Relations with the United States Derek E. Mix Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress view the United Kingdom (UK) as the United Specialist in European States’ closest and most reliable ally. This perception stems from a combination of factors, Affairs including a sense of shared history, values, and culture; a large and mutually beneficial economic relationship; and extensive cooperation on foreign policy and security issues. The UK’s January 2020 withdrawal from the European Union (EU), often referred to as Brexit, is likely to change its international role and outlook in ways that affect U.S.-UK relations. Conservative Party Leads UK Government The government of the UK is led by Prime Minister Boris Johnson of the Conservative Party. Brexit has dominated UK domestic politics since the 2016 referendum on whether to leave the EU. In an early election held in December 2019—called in order to break a political deadlock over how and when the UK would exit the EU—the Conservative Party secured a sizeable parliamentary majority, winning 365 seats in the 650-seat House of Commons. The election results paved the way for Parliament’s approval of a withdrawal agreement negotiated between Johnson’s government and the EU. UK Is Out of the EU, Concludes Trade and Cooperation Agreement On January 31, 2020, the UK’s 47-year EU membership came to an end. -

Triangle of Partnership Or Conflicts

International Journal of Political Science (IJPS) Volume 4, Issue 4, 2018, PP 34-41 ISSN 2454-9452 http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-9452.0404006 www.arcjournals.org Turkey in Relation to EU and Russia - Triangle of Partnership or Conflicts Bulent Acma1*, Mehmet Ali Ozcobanlar2 1Anadolu University, Department of Economics, Eskisehir/Turkey. 2Department of Management, University of Warsaw, Warsaw/Poland *Corresponding Author: Bulent Acma, Anadolu University, Department of Economics, Turkey Abstract: EU-Turkey-Russia. In this research, the relationship between European Union and Turkey, an age long neighbour to the continent and an associate member of European Union since 1963, are examined and analysed. Turkey is an important ally of the union and the only Muslim country-member of NATO from the very beginning of the treaty, since it joined the organization in 1952, at the same year that Greece did. The relations between the Union and Turkey are examined from the aspect of security. The reactions of the European Union to the recent political changes in Republic of Turkey, after the 15 July 2016 failed coup- attempt, are also examined. The EU - Turkey relations after the failed coup attempt and the international impact of it are studied from the perspective of political and social influence it might have. Russia is a vital energy supplier to the Union and Turkey is a geopolitical bridge between west and east, an energy corridor standing at the crossroad of important energy markets such as Iran, Iraq and Azerbaijan. The country has also relations with Cyprus, an upcoming gas supplier and an EU member.