Property Rate in Ghana: a Poor Local Revenue Source Or Underexploited Potential?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNDP, Ghana 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

1 © UNDP, Ghana 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This synthesis report draws on background papers prepared by a team of consultants as well as engagements with experts and policy makers. See Acknowledgments. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP, or their Member States. Please note that the electronic copy of the report corrects for some errors and typos which were there in the first printed version. It also takes on board some of the important suggestions from reviewers which came after the report went to print. No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of UNDP, Ghana Cover Design by Yamens Press Limited. Printed by Yamens Press Ltd. ii PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... X FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................. XII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... XIV ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... XVI NORTHERN GHANA HDR: HIGHLIGHTS ......................................................................................... xx CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION AND APPROACH -

Community-Based Ecotourism Potential: a Case Study of Sankana Slave Caves in Nadowli-Kaleo

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Applied Science (IJRIAS) |Volume VI, Issue V, May 2021|ISSN 2454-6194 Community-based Ecotourism Potential: A Case Study of Sankana Slave Caves in Nadowli-Kaleo District of Upper West Region, Ghana Cornelius K.A. Pienaah1*, Bruno Berewono2, Danganaa Mahama3, Jane Akanzum4 1Faculty of Natural Resources and Environment, Department of Environment and Sustainability Sciences, University for Development Studies, Ghana 2Faculty of Integrated Development Studies, Department of Social and Development Administration, Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Ghana 3Faculty of Natural Resources and Environment, Department of Environment and Sustainability Sciences, University for Development Studies, Ghana 4College of Art and Built Environment, Department of Planning, Kwame Nkrumah University for Science and Technology, Ghana *Corresponding Author Abstract: A major feature of the Upper West Region is its ancient „purposeful travel to natural areas to understand the culture caves. The caves found in Sankana, Bulenga and Dahili, were and natural history of the environment, taking care not to alter places of refuge for the inhabitants who were fleeing the slave the integrity of the ecosystem, while producing economic raiders. Slave Camps can be found at Pizaga and Dolbizon and opportunities that make the conservation of natural resources Slave market at Kassana and Salaga in the Upper East and beneficial to local people (OMT, 2014, p. 15‟ cited in Yasu C. Savannah Regions respectively. The study explored on the potential, strategies as well as effects of developing the Sankana Martinez and Mara Rosas Baños). Slave Caves as an ecotourism destination in light of the main In general, ecotourism provides many jobs to Ghanaians and pillars of sustainable development (economic, social/cultural, and has enormous potential as a catalyst for future economic and environmental). -

British Journal of Pharmacology

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES SCHOOL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY HEALTH DISTRICT INEQUITIES IN HOUSEHOLD CHILD SURVIVAL PRACTICES IN THE UPPER WEST REGION OF GHANA EASMON OTUPIRI FEBRUARY 2012 DISTRICT INEQUITIES IN HOUSEHOLD CHILD SURVIVAL PRACTICES IN THE UPPER WEST REGION OF GHANA By Easmon Otupiri A thesis submitted to the Department of Community Health, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (COMMUNITY HEALTH) School of Medical Sciences College of Health Sciences FEBRUARY 2012 i DECLARATION The work described in this thesis was carried out at the Department of Community Health, KNUST-School of Medical Sciences. I declare that, except for references to other people’s work, which I have duly acknowledged, this thesis is original to me. This work has not been submitted either completely or in part for the award of any other degree in this or any other university. ……………………….. …………………………………. Easmon Otupiri Date …………………………. ……………………………….. Prof. Michelle J Hindin Date (Supervisor) …………………………… ………………………………. Rev. (Dr.) ENL Browne Date (Supervisor) ………………………….. ……………………………… Dr P Agyei-Baaffour Date (Head of Department) ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my parents (Mr William Otupiri and Mrs Comfort Otupiri), my wife (Joana) and children (Kwabena, Abena and Akosua) for all the encouragement you gave me to get this thesis completed. I love you very much. iii ACKNOWLEDEMENT I am very grateful to the Lord God Almighty who through His abundant mercy, endless grace and everlasting love made this work possible. My sincere thanks go to my supervisors: Prof. -

Newsletter No

GES-JICA INSET Project Newsletter No. 2 of 2008 (October 2008) GES-JICA Project to Support the Operationalization of the In-Service Training Policy (INSET Project) supports the smooth implementation of INSET for primary school teachers in 10 districts. It aims at developing a structured and replicable INSET model for primary school Science and Mathematics. This 5th and final newsletter is for the Project reports on the structure of activities and achievements of the Project from December 2005 to November 2008. It also highlights plans for Nationwide INSET. Subsequent issues would be produced by INSET Programme of GES. curriculum leader coordinate and organize SBI/CBI Background of the INSET Project effectively. In August 2005, Japan International Cooperation Agency 2. Monitoring and evaluation system for the district INSET (JICA) in collaboration with Ghana Education Service started model has been developed and is being implemented. a master plan implementation structure to institutionalise INSET in primary schools. The project’s INSET model took 3. The project implementation structure and monitoring & into account the following: evaluation system mentioned above are included in the 1. Establishment of implementation structure National and District Guidelines and need-based INSET 2. Establish monitoring and evaluation system modules (Sourcebooks) that have been produced. 3. Developing training modules 4. Undertaking capacity building 5. Using SBI/CBI as a cost effective INSET The overall purpose of the project was to develop a structured and replicable INSET model for primary school teachers in 10 pilot districts. Achievements of the INSET Project 1. Project implementation structure has been established as seen in the diagram below. -

Upper West Regional Health Services 2008 ANNUAL REPORT Dr. Alexis

Upper West Regional Health Services 2008 ANNUAL REPORT Dr. Alexis Nang-beifubah Regional Director of Health Services 12 March 2009 Executive Summary This report is an embodiment of how the health sector faired in the Upper West Region in the year 2008. The records point to some achievement amidst serious constraints. Transport and communication networks are not the best in the region. The proliferation and expansion of mobile telecommunication and radio networks has enhanced communication and information dissemination in the region. Currently, there are five radio stations, two TV networks and three mobile telecommunication networks operating in the region. With regards to the road network, only two of the nine districts are linked to the regional capital by tarred roads. For the untarred roads, the least one probably talks about them, the better as they are mostly horrible to travel on especially, during the rainy season. To overcome the challenges encountered in 2007 and other emerging ones, the region’s outlined priorities were to: sustain the high impact rapid delivery interventions; increase access (scaling of CHPS and NHIS); strengthen monitoring, supervision and performance management systems; improve quality assurance and customer care; strengthen disease surveillance/disaster preparedness and response/control; strengthen regenerative health and nutrition programme in all districts; and campaign on alcoholism The region, during the year, implemented activities aimed at reducing the high maternal and child mortality rates. The achievements in service delivery were remarkable with the reduction or stagnation in coverage for some sector-wide indicators. Immunization coverage using the pentavalent 3 vaccine as proxy reduced from 109% in 2007 to 82% in 2008. -

Feed the Future Indicators for Upper West Region, Ghana 2015 District Baseline Estimates

FEED THE FUTURE INDICATORS FOR UPPER WEST REGION, GHANA 2015 DISTRICT BASELINE ESTIMATES USAID-METSS JULY 2016 Report Contact: Dr. Yacob Zereyesus METSS Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 Telephone: +1 785-532-4438 Email: [email protected] Maps Created By: Jennifer Asiedu-Dartey (METSS Accra Office) Recommended Citation: Guvele, C.,Y.A. Zereyesus, K.L. Ross , E.G. Gutierrez, A. Mzyece, and V. Amanor-Boadu. 2016. Feed the Future Indicators for Upper West Region, Ghana 2015 District Baseline Estimates. Manhattan, KS: Department of Agricultural Economics, Kansas State University Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................................. i List of Tables ..................................................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures.................................................................................................................................................... iv List of Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................... v Introduction and Background ........................................................................................................................ 1 Purpose of Report ......................................................................................................................... -

Sissala West District

SISSALA WEST DISTRICT , Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Sissala West District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

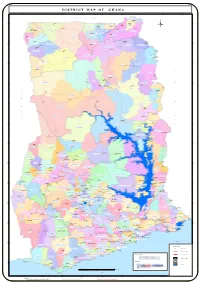

Page 1 "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "

D I S T R I C T M A P O F G H A N A 3°0'0"W 2°30'0"W 2°0'0"W 1°30'0"W 1°0'0"W 0°30'0"W 0°0'0" 0°30'0"E 1°0'0"E B U R K I N A F A S O BAWKU MUNICIPAL Pusiga Bawku J" J" PUSIGA 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N Gwollu Paga Binduri J" J" J" Zebilla BONGO J" BINDURI Bongo KASENA NANKANA WEST Navrongo KN WEST J" NANDOM Tumu J" Ü J" Garu LAMBUSSIE KARNI J" J" Nangodi J" J" SISSALA WEST Nandom Lambusie NABDAM BAWKU WEST BOLGATANGA GARU TEMPANE MUNICIPAL J" KASENA NANKANA Sandema Bolgatanga J" EAST Tongo BUILSA NORTH J" TALENSI Lawra J" LAWRA SISSALA EAST JIRAPA Jirapa Gambaga J" J" J" 10°30'0"N 10°30'0"N BUILSA SOUTH Bunkpurugu DAFFIAMA BUSSIE Fumbisi " MAMPRUSI EAST Daffiama J BUNKPURUGU YONYO J" WEST MAMPRUSI Nadawli J" J" Walewale Funsi NADOWLI-KALEO J" J" Yagaba MAMPRUGU MOAGDURI CHEREPONI Chereponi WA EAST J" Wa J" WA MUNICIPAL 10°0'0"N 10°0'0"N KARAGA GUSHIEGU Karaga J" J" Gushiegu R WA WEST Wenchiau J" E KUMBUMGU SABOBA P NORTH GONJA J" SAVELUGU NANTON Saboba Savelugu J" U Kumbungu TOLON J" J" B 9°30'0"N SAWLA/TUNA/KALBA Daboya YENDI MUNICIPAL 9°30'0"N Yendi Tolon SAGNERIGU Sagnarigu Sang J" J" J" J" L J" Tamale Tatale TAMALE NORTH SUB METRO MION J" I C Zabzugu Sawla J" J" O C TATALE T WEST GONJA ZABZUGU E Damongo J" Bole O J" 9°0'0"N 9°0'0"N NANUMBA NORTH F D' GONJA CENTRAL Bimbila J" I Buipe T V J" NANUMBA SOUTH BOLE O Wulensi O J" I G Salaga NKWANTA NORTH R J" Kpasa 8°30'0"N 8°30'0"N EAST GONJA Kpandai J" O E J" KPANDAI KINTAMPO NORTH NKWANTA SOUTH BANDA Nkwanta J" Yeji J" KRACHI NCHUMURU Banda Ahenkro J" Chindiri PRU J" Kintampo J" J" Dambai 8°0'0"N -

The Role of Traditional Bone Setting in Primary Fracture Care in the Upper West Region: the Cases of Jonga, Gwollu and Doung Bone-Setting Centres

www.udsspace.uds.edu.gh UNIVERSITY FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES THE ROLE OF TRADITIONAL BONE SETTING IN PRIMARY FRACTURE CARE IN THE UPPER WEST REGION: THE CASES OF JONGA, GWOLLU AND DOUNG BONE-SETTING CENTRES. BY CONSTANCE SABIRU AKURUGU THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF AFRICAN AND GENERAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT STUDIES, UNIVERSITY FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES August, 2011 www.udsspace.uds.edu.gh www.udsspace.uds.edu.gh Abstract For majority of people in rural areas, traditional bone setting is the first port of call as well as last resort if orthodox medicine fails. However, traditional bone setting has not been given its due recognition. For instance it is ignored in reports on the state of Ghanaian medicine. Also, some allopathic practitioners contend that traditional bonesetters do try and error and thus are without skills. This study examined the role of traditional bone setting in primary health care in the Upper West Region. The study, located in three Bone Centres in three districts within the Upper West Region adopted a mixed methods research approach. The study adopted a multi-stage purposive sampling technique. In the first stage, a typical case sampling technique was used to select the Bone-setting Centres. In the second stage, intensity sampling technique was used to select heads of bonesetters for in- depth discussions. All patients undergoing treatment at the centres were interviewed. At the institutional level, intensity sampling technique was used to recruit directors and other stakeholders of health care in the Upper West Region. -

Scarification and Tribal Marking in Ghana

An Ancient Practice: Scarification and Tribal Marking in Ghana Alyssa Irving Independent Study Project HCAD, Fall 2007 1 Acknowledgements The past three months have been a time of great personal growth and fulfillment in my life. I could never ask for a more remarkable or eye-opening experience. The history related to me here has re-shaped the way I look at Africa as a continent, Ghana as an independent country, and indeed the world. The lessons learned here will never be forgotten, and I must thank all those people who made it possible. I thank my mom for believing in me always and making this entire trip possible. Thank you Aunte Naana, for creating this opportunity for me to come to Ghana and learn more than I ever thought possible about the history of the slave trade and Ghana. No words can do justice to what I’ve taken from this experience. I thank Uncle Ebo for being such a positive and enlightening presence in my time here. You opened your home to me and took care of me in a way that I will never forget. Your visions for your community and country are beautiful and I look forward to seeing all the wonderful progress you will make in the upcoming years. I thank Uncle Eric for always being that person I knew I could go to when my ideas were scattered and I needed focus. Your open-mindedness allowed me to relax and let my project take on different forms than I’d initially expected. Thank you Lydia for being a constant presence on excursions and always making sure we had food in our bellies and Milo to drink during break times. -

Upper West Regional Health Services 2012 Annual Report

Upper West Regional Health Services 2012 Annual Report Dr. Alexis Nang-beifubah Regional Director of Health Services March 2013 FOREWORD The 2012 Annual Health Sector Performance report captures information on key health sector strategies and specific interventions that were implemented during the year in line with the sector policies. During the period under review the perennial shortage of critical staff such as midwives, medical assistants and doctors as well as poor health infrastructure still persisted. There was also the emergent problem of a prolong (5 months) delay in reimbursement of NHIS funds to health facilities bringing untold difficulties to management of hospitals and health centres that rely on IGF from the NHIS as their main source of income. The Regional Health Directorate and all BMCs also experienced erratic flow of funding from central government as well as a decline in donor support. Other issues of concern such as high infant and maternal deaths, inadequate monitoring and supervision, and weak clinical services also confronted the region in the year. The challenges in the detection and control of key epidemic prone diseases were also encountered. Despite these challenges, the Regional Health Directorate adopted several innovative strategies that brought positive results in most of the key service delivery areas such as Reproductive and Child Health, Disease Surveillance and control and Clinical Care services. Most of the Sector wide Indicators in these service areas have improved as captured in our routine service data for 2012 as well as corroborated in national surveys as the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS). The modest achievements made can be attributed to our dedicated health staff, community based volunteers, local governments at all levels, the people of the Upper West region, our development partners such as UNICEF, JICA, , UNFPA, Plan Ghana, World Vision etc. -

You Must Read the Following Disclaimer Before Continuing. The

IMPORTANT NOTICE IMPORTANT: You must read the following disclaimer before continuing. The following disclaimer applies to the Base Offering Circular following this notice, and you are therefore advised to read this disclaimer carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the attached Base Offering Circular. In accessing the attached Base Offering Circular, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them from time to time, each time you receive any information from the Issuer or the Dealers as a result of such access. Confirmation of Your Representation: By accessing the attached Base Offering Circular you have confirmed to Citigroup Global Markets Limited, Merrill Lynch International, Rand Merchant Bank, a division of FirstRand Bank Limited (London Branch), Standard Chartered Bank, The Standard Bank of South Africa Limited, CalBank PLC, Databank Brokerage Limited, Fidelity Bank Ghana Limited, IC Securities (Ghana) Limited and Temple Investments Limited (together, the “Dealers” and each a “Dealer”) and the Republic of Ghana (the “Issuer”) that (i) you understand and agree to the terms set out herein, (ii) you are either (a) a person who is outside the United States and that the electronic mail address you have given is not located in the United States, its territories and possessions, or (b) a person that is a “Qualified Institutional Buyer” (a “QIB”) within the meaning of Rule 144A under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”) ("Rule 144A") that is