2244-5226 Framing Disaster Among

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REGISTERED SHIPBUILDING and SHIP REPAIR ENTITY with FACILITIES, MANPOWER & CAPITALIZATION in CENTRAL OFFICE (As of DECEMBER 2019)

REGISTERED SHIPBUILDING AND SHIP REPAIR ENTITY WITH FACILITIES, MANPOWER & CAPITALIZATION IN CENTRAL OFFICE (as of DECEMBER 2019) CATEGORY/ LICENSED EQUITY MODE OF FACILITIES MANPOWER No. COMPANY CONTACT PERSON CLASSIFI- VALIDITY PARTICIPATION ACQUISITION GRAVING BUILDING FLOATING SLIPWAY/ TECHNICAL SKILLED SYNCHROLIFT CATION FIL (%) FORGN (%) OWNED LEASED DOCK YARD DOCK LAUNCHWAY PERM'T CONT'L PERM'T CONT'L 1 HERMA SHIPYARD INC. Engr. ROMMEL S. PERALTA A Sep 13, 2023 100% - - 15,000 GT 19,840 m 2 1,600 GT - 120 x 20 m 11 13 49 340 Herma Industrial Complex Yard Service Manager (154.50 x 31 (60.96 x Mariveles, Bataan herma.com.ph BATAAN BASECO JOINT x 12.20 m) 19.51 m) VESTURE, INC. Tel No. 047-9354368 Jun 26 2000 to Jun 25 2025 (25 yrs) 2 KEPPEL SUBIC SHIPYARD, INC. Ms. DINAH LABTINGAO A Sep 28, 2020 0.05% 99.95% OWNED - 550,000 170,000 m 2 - Gantry 300 x 65 m 33 10 119 290 Special Economic Zone, Cabangaan Accounting Manager DWT (shipyard area) Crane Pt., Cawag, Subic, Zambales [email protected] (1,500 tons) Tel No. 047-2322380 3 SUBIC DRYDOCK CORPORATION Mr. THOMAS J. PETRUCCI A Oct 02, 2020 99.80% 0.20 % - - 29,143 m 2 18,000 DWT - - 7 - 28 - Bldg. 17 Gridley cor. Schley Roads General Manager (american) 4,000 DWT SBMA SRF Cmpd., Subic Bay Freeport [email protected] Jun 20 2010 to Feb 20 2021 Zone Tel No. 047-2528183/ (11 yrs) 85/89 4 DANSYCO MARINE WORKS & Mr. DARY SY B Apr 02, 2019 100% - - - 1,800 m 2 - - High Blocks 5 - 48 - SHIPBUILDING CORP. -

11 SEPTEMBER 2020, FRIDAY Headline STRATEGIC September 11, 2020 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 2 Opinion Page Feature Article

11 SEPTEMBER 2020, FRIDAY Headline STRATEGIC September 11, 2020 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 2 Opinion Page Feature Article Cimatu aims to increase the width of Manila Bay beach Published September 10, 2020, 7:55 PM by Ellayn De Vera-Ruiz Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Secretary Roy Cimatu said beach nourishment in Manila Bay may help increase the width of the beaches as they are “very narrow.” Environment Secretary Roy A. Cimatu (RTVM / MANILA BULLETIN) This was part of the DENR’s response to a letter sent by the office of Manila Mayor Isko Moreno last Sept. 7, seeking the agency’s clarification on the safety of dolomite to public health. In his response dated Sept. 8, Cimatu pointed out that beach nourishment is the practice of adding sand or sediment to beaches to combat erosion and increase beach width. Beach nourishment, he explained, should be applied in Manila Bay because “Manila Bay is not considered prone to coastal erosion as it is mostly protected by seawalls, but the beaches are very narrow.” He cited that under the writ of continuing Mandamus issued by the Supreme Court on Dec. 18, 2016, a marching order was given to 13 government agencies, including the DENR to spearhead the clean up, rehabilitation, and preservation of Manila Bay “to make it more suitable for swimming, skin diving, and other forms of contact recreation and for protection of coastal communities.” “After dredging and clean up of the Bay, it was agreed upon by members of the different agencies involved in the rehabilitation of Manila Bay that the initial beach nourishment in Manila Bay will be applied in segment between the area fronting the US Embassy and the Manila Yacht Club to mimic a sort of a ‘pocket beach,’ the northern portion protected by the compound of the US Embassy and the south side sheltered by the Mall of Asia compound,” the letter read. -

E:\Kasarinlan 22, 2-Pagemaker 7 Lay Out\08-WATANABE.Pmd

68 MIGRANT MUSLIM COMMUNITIES IN MANILA Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies 2007 22 (2): 68-96 The Formation of Migrant Muslim Communities in Metro Manila AKIKO WATANABE ABSTRACT. The paper examines the formation of migrant Muslim communities in Metro Manila set against the Philippine government’s changing policies toward the Muslim Filipinos in Mindanao at the turn of the twenty-first century. The Muslim Filipinos’ migration to Metro Manila has been steered by kin and ethnic relations and religious tolerance. This, in turn, resulted in ethnic and economic stratifications in and among the migrant Muslim communities in Metro Manila. The paper analyzes these communities and the dynamics that structure Muslim Filipinos’ spatial movements in and around Metro Manila. KEYWORDS. Muslim Filipinos · migration · Metro Manila · communities INTRODUCTION This paper examines the formation of Muslim communities in Metro Manila1 in relation to the changing government policies toward Muslim Filipinos in Mindanao at the turn of the twenty-first century. It typifies and analyzes the various communities that have emerged in the area and the dynamics that structure Muslim Filipinos’ spatial movements. Muslims in the Philippines, also known as Moros,2 are part of thirteen ethnolinguistic groups, each with a home region in parts of Mindanao and Sulu described as the Muslim South. These areas have 3.5-4.0 million Muslim inhabitants, making up nearly 5-10 percent of the total national population. 3 The formation of migrant Muslim Filipino communities outside Mindanao has deep historical roots that became more pronounced with the armed conflict in Mindanao and Sulu in the late 1960s. -

CH-CP-PH-BASECO Reclamation Coastal Protection with Mactube

CASE HISTORY Rev: 02, Issue Date : May 2015 BASECO RECLAMATION COASTAL PROTECTION BASECO Compound, Manila City, Philippines ENVIRONMENTAL / HYDRAULIC / COASTAL PROTECTION Products: MacTube, MacTex Woven & Nonwoven Geotextiles, Gabions Problem The Philippine Reclamation Authority (PRA) has pro- posed another ten-hectare reclamation project for a socialized housing at the Bataan Shipping and Engi- neering Company (BASECO) Compound, Manila City, Philippines. This project is an extension of the previ- ously constructed 256-hectare reclamation project by the PRA. The project was awarded to a FF Cruz & Construction Inc. A containment wall is needed to be constructed on the existing breakwaters to protect the area from coastal erosion resulting from effects of waves and tidal changes. The Contractor decided to look for an alternative system of appropriate materials needed to prevent erosion of the filling materials (sands) to be contained behind the existing breakwaters. Solution Despite another brand was recommended and shown as specified on plans, the Contractor - having a good rela- tionship with Maccaferri and is satisfied of the quality of Maccaferri products, sought Maccaferri’s proposal on the project. FFCCI and Maccaferri introduced the materials to the Before Construction September 2007 Project Owner for approval. Eventually, the materials were approved for the project. Project Owner Philippine Reclamation Authority General Contractor FF CRUZ & CONSTRUCTION INC. Consultant Maccaferri Products 1,200 l.m. MacTube Geosynthetic Tube 11,200 sq.m. MacTex Nonwoven Geotext 21,700 sq.m. MacTex WR12S 950 pcs Zinc-coated Gabions Construction Info Start of Construction : December 2008 Completion Date : March 2009 Before Construction November 2008 Engineering a Better Solution BASECO RECLAMATION COASTAL PROTECTION BASECO Compound, Manila City, Philippines Project Cross Section During Construction December 2008 MACCAFERRI (PHILIPPINES), INC. -

Highlights of Accomplishment Report CY 2016

Highlights Of Accomplishment Report CY 2016 Prepared by: Corporate Planning and Management Staff Table of Contents TRAFFIC DISCIPLINE OFFICE ……………….. 1 TRAFFIC ENFORCEMENT Income from Traffic Fines Traffic Direction & Control; Metro Manila Traffic Ticketing System 60-Kph Speed Limit Enforcement Bus Management and Dispatch System South West Integrated Provincial Transport System (SWIPTS) Enhance Bus Segregation System (EBSS) Anti-Illegal Parking Operations Enforcement of the Yellow Lane and Closed-Door Policy Anti-Colorum and Out-of-Line Operations Anti-Jaywalking Operations EDSA Bicycle-Sharing Scheme Operation of the TVR Redemption Facility Personnel Inspection and Monitoring Road Emergency Operations (Emergency Response and Roadside Clearing) Unified Vehicular Volume Reduction Program (UVVRP) Towing and Impounding Other Traffic Management Measures implemented in 2016 TRAFFIC ENGINEERING Design and Construction of Pedestrian Footbridges Upgrading of Traffic Signal System Application of Thermoplastic and Traffic Cold Paint Pavement Markings Traffic Signal Operation and Maintenance Fabrication and Manufacturing/ Maintenance/ Installation of Traffic Road Signs/ Facilities Other Special Projects TRAFFIC EDUCATION Institute of Traffic Management Other Traffic Improvement-Related/ Special Projects/ Activities Metro Manila Traffic Navigator MMDA Twitter Service MMDA Traffic Mirror Implementation of Christmas Lane Oplan Kaluluwa (All Saints Day Operation) METROBASE FLOOD CONTROL & SEWERAGE MANAGEMENT OFFICE (FCSMO) -

DEPARTMENT of PUBLIC WORKS and HIGHWAYS SOUTH MANILA DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Th 8 Street, Port Area, Manila

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS SOUTH MANILA DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION th 8 Street, Port Area, Manila INVITATION TO BID 1. Contract ID No. 17OH0113 Contract Name: Completion/Repair/Renovation/Improvement of Various Facilities at DPWH Central Office Building- Civil and Sanitary/Plumbing Works, Bonifacio Drive, Port Area, Manila Contract Location: Manila City Scope of Work: Completion/Repair/Renovation/Improvement of Various Source of Fund and Year: 01101101-Regular Agency Fund-General Fund-New General Appropriations- Specific Budgets of National Government Agencies Approved Budget for the Contract (ABC): (₱ 31,392,668.06) Contract Duration: 360 cal. Days Co t of Bid Docu ent : ₱ 25,000.00 2. Contract ID No. 17OH0114 Contract Name: Proposed Rainwater Collector System at: a) Silahis ng Katarungan, 1520 Paz St. Paco, Manila; b) Technological University of the Philippines, Ayala Blvd., Ermita, Manila; c) Normal University Taft Ave., corner Ayala Blvd., Ermita, Manila; d) Bagong Barangay Elementary School, J. Zamora, Pandacan, Manila; e) Bagong Diwa Elementary School 2244 Linceo St., Pandacan, Manila; f) Beata Elementary School, Beata corner Certeza St., Pandacan, Manila; g) T. Earnshaw Elementary School, A. Bautista St., Punta, Sta. Ana, Manila; h) Pio del Pilar Elementary School, Pureza St., Sta. Mesa, Manila; i) Geronimo Santiago Elementary School, J. Nepomuceno St., San Miguel, Manila; j) J. Zamora Elementary School, Zamora St., Pandacan, Manila; k) Sta. Ana Elementary School, M. Roxas St., Sta. Ana, Manila; l) Mariano Marcos Memorial High School, 2090 Dr. M. Carreon St., Sta. Ana, Manila; m) C.P. Garcia High School, Jesus St., Pandacan, Manila; n) Benigno Aquino Elementary School, BASECO Compound, Port Area, Manila; o) E. -

“License to Kill”: Philippine Police Killings in Duterte's “War on Drugs

H U M A N R I G H T S “License to Kill” Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs” WATCH License to Kill Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs” Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34488 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34488 “License to Kill” Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs” Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 24 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 25 I. -

~~2~1929Id ~Epnhltc of Tbe ~Biltppines ~Upreme QI:Ourt :Iflf(Aniln SECOND DIVISION

rm SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIFPINES PUILIC INFOl'lM~TION OFFICE ~~2~1929iD ~epnhltc of tbe ~biltppines ~upreme QI:ourt :iflf(aniln SECOND DIVISION RAMON PICARDAL y BALUYOT, G.R. No. 235749 ' Petitioner, Present: CARPIO, J., Chairperson, PERLAS-BERNABE, - versus - CAGUIOA, J. REYES, JR., and LAZARO-JAVIER, JJ. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Promulgated: Respondent. 1 9 JUN 2019 x------------------------------------~~fiJ;;l-x DECISION CAGUIOA, J.: Before the Court is a Petition for Review on Certiorari1 (Petition) filed by accused-appellant Ramon Picardal y Baluyot (Picardal) assailing the Decision2 dated May 31, 2017 and Resolution3 dated October 27, 2017 of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. CR No. 38123, which affirmed the Decision4 dated September 24, 2015 of the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 21 (RTC) in Criminal Case No. 14-304527, finding Picardal guilty beyond reasonable· doubt of the crime of Qualified Illegal Possession of Firearms. The Facts An Information5 was filed against Picardal for Qualified Illegal Possession of Firearms, the accusatory portion of which reads: That on or about March 28, 2014, in the City of Manila, Philippines, the said accused did then and there willfully and unlawfully have in his possession and under his control one (1) caliber .3 8 revolver 1 Rollo, pp. 12-27. 2 Id. at 29-40. Penned by Associate Justice Socorro 8. Inting, with Associate Justices Romeo F. Barza and Ramon Paul L. Hernando (now a Member of this Court) concurring. 3 Id. at 42-43. 4 Id. at 60-66. Penned by Presiding Judge Alma Crispina B. Collado-Lacorte. -

MAIP AUGUST 2019.Pdf

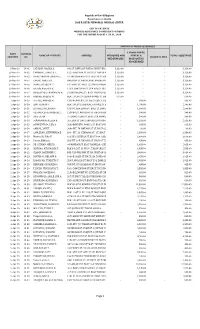

Republic of the Philippines Department of Health JOSE R. REYES MEMORIAL MEDICAL CENTER LIST OF PATIENTS MEDICAL ASSISTANCE TO INDIGENT PATIENTS FOR THE PERIOD AUGUST 1 TO 31, 2019 AMOUNT OF MEDICAL SERVICES LABORATORIES, DATE CONTROL NAME OF PATIENTS ADDRESS MEDICINES AND DENTAL & TOTAL ASSISTANCE GRANTED NO. HOSPITAL FEES MED SUPPLIES DIAGNOSTICS PROCEDURES 8-Mar-19 19-01 CATALAN, ROSELA L. 042 ST. JOHN SAN PAULO SUBDV. BRGY NAGKAISANG 3,120.00 NAYON NOVALICHES, - QC QUEZON CITY - 3,120.00 25-Mar-19 19-02 TAMBONG, CARLITO S. 1529 DAGUPAN ST. BRGY 51 TONDO MANILA 3,120.00 - - 3,120.00 26-Mar-19 19-03 VIRAY, SHAYNE LORAINE C. 47 BAL\KAWAN ST ST. BRGY VETERANS VILL. 3,120.00QUEZON CITY - - 3,120.00 26-Mar-19 19-04 CARAIG, MOISES B. BALAYAN ST. BRGY LANATAN BALAYAN BATANGAS 3,120.00 - - 3,120.00 27-Mar-19 19-05 PIANG, SHIRELYN T. 167 RUBY ST. BRGY 122 TONDO MANILA 3,120.00 - - 3,120.00 29-Mar-19 19-06 Estrada, Manuel Jr E. 115 R. SANTIAGO ST. 9TH AVE ST. BRGY NONE 3,120.00CALOOCAN CITY - - 3,120.00 29-Mar-19 19-07 BRILLANTES, CHARMAINE N. 54 BARTOLOME ST. BRGY VIENTE REALES VALENZUELA 3,120.00 CITY - - 3,120.00 20-Mar-19 19-08 SABDAO, ARLENE M. BLK. 11 LOR 37 CELINA HOMES ST. BRGY 168 DEPARO 910.00 CALOOCAN CITY - - 910.00 1-Apr-19 19-09 CORTEZ, ANDRES M. 1300 ACAPITA ST ST. BRGY GEN. T. DE LEON VALENZUELA - CITY 985.00 - 985.00 1-Apr-19 19-10 IBAY, GLORIA V. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION the Primary Purpose of This Thesis Is To

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The primary purpose of this thesis is to evaluate the level of preparedness of the Barangay Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Committee (BDRRMC) of Barangay No. 649, Zone 68, Manila, in order to address the gap between the concerned barangay’s disaster risk reduction and management projects and activities and the present strength and direction of the preparedness of the BDRRMC. This study aims to categorize the measurement of community disaster preparedness efficiency in terms of the so-called 4 C’s, namely: Community Risk Assessment, Contingency Planning, Communication System and Capacity-Building. It also intends to find out if there is any significant relation between the profile and the level of preparedness of the concerned BDRRMC members. With all these in mind, the researchers have agreed that by staying true to the course of this study they shall be able to achieve their desired objectives as well as produce their intended outputs: a valid and useful evaluation tool for disaster preparedness of any Barangay Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Committee and a program of action to make them well-prepared in responding to disasters. 2 What are these so-called 4 C’s being harped on by the researchers of this study? The 4 C’s actually represent the priority areas of concern for disaster preparedness which will help the researchers formulate the general statement of the problem as well as rationalize the corresponding findings, conclusions and recommendations of this thesis. It will also help them define the scope and delimitations of this study. The first C, Community Risk Assessment. -

Fishers Rise Up! (Ahon Mangingisda!) Filipino Fishers’ Climate Strike

Fishers Rise Up! (Ahon Mangingisda!) Filipino fishers’ Climate Strike Context The year 2050 is the year that climate experts warn of the ‘great flood’ that would submerge the lands housing 300 million people across the world, at conservative estimates. As the climate scientist group Climate Central’s recent study identified Asia as the most vulnerable in the event of the rising seas, the Philippines, as an archipelago, will always bear the brunt of the calamitous elevated levels of the world’s oceans ramming on our coastlines. This forecast spells disaster to the Philippines, which is composed of more than 7, 100 islands and with 60% of its total population directly and indirectly related to the coastal geography. The study also shows that residences of 8 million families in Metro Manila would likely be submerged by the projected sea rise of about 2-7 feet, and possibly more. The coastal population, most especially the fisherfolk sector, who directly subsists in seas for living, bears the brunt of this looming ecological disaster. While these studies pinned the changing climate, primarily the global warming, as the main culprit of the rising level of waters, it is important to address the underlying factors of climate change. Projects for development aggression in the form of large-scale mining and logging activities, conversion of productive farm lands into agri-business and eco-tourism ventures, and dumping and filling of seas, also known as land reclamation, are among the biggest threats to the environment, both marine and land. These projects, which are profit-driven, continue to cost the environmental and socio-economic rights of the most vulnerable sectors. -

50Th Anniversary…

50th Anniversary… COMPANY PROFILE (Rev.17-Apr 2017) • sheet 1 of 31 I. BRIEF HISTORY GEOTECHNICS PHILIPPINES, INCORPORATED, was founded and organized on October 04, 1966 and registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission on October 18 of the same year. It is composed of a group of professionals, each respected in their own fields of endeavor. It’s preliminary goal was to provide geotechnical consulting services and carry a general contracting business in all kinds of construction, mining, manufacturing and infrastructure activities. With the purpose of providing technological assistance to the ever-increasing needs of the industrialization of the country, the company has expanded its services in Geotechnical Engineering and it has gained the statue as one of the leading corporations in its field. From a meager capital of Php250,000.00, it is now operating on a capital base of Php20M. ACCREDITATION AND MEMBERSHIP • Philippine Constructors Association (PCA member) • PCAB - General Engineering B CIAP - Dept. of Trade and Industry (DTI) • Accredited testing laboratory - Bureau of Research and Standard (DPWH) • Accredited Driller - National Water Resources Board (NWRB) • Council of Engineering Consultants of the Philippines – (CECOPHIL)-Member II. VISION STATEMENT To meet global standards and provide technological innovation for premium value geotechnical services and reliable results. Maintain the safety/quality requirements and continuous recognition. MISSION STATEMENT To provide cost effective solutions, safe and timely delivery of service for the satisfaction and needs of the Client. POLICY ON QUALITY The management and staff of GEOTECHNICS PHILIPPINES, INC. (GPI) is committed to satisfy customer satisfaction of packaging accurate test reports with an assured level of quality.