E:\Kasarinlan 22, 2-Pagemaker 7 Lay Out\08-WATANABE.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

The Filipino People Seethe with Anger and Discontent

May - August 2013 Released by KARAPATAN (Alliance for the Advancement of People’s Rights) he Filipino people seethe with anger and discontent. TThe protest actions that followed the exposé on the PhP10-billion pork barrel scam sent the Aquino government scampering for ways to dissipate the people’s anger, but only in ways that Benigno Simeon Aquino III and the bureaucrats in his government can continue to feast on the pork and drown themselves in pork fat. The people’s anger is not only directed at the 10 billion-peso scam but also against the corruption that goes on with impunity under BS Aquino, who ironically won under an anti-corruption slogan “kung walang kurap, walang mahirap”. The Aquino government could no longer pretend to be clean before the Filipino people. PINOY WEEKLY Neither can it boast of improving the poor people’s lives. The reluctance of Aquino and labor, the country remains allegedly had an encounter with an his allies to do away with the PhP25- backward; the ordinary wage undetermined number of New People’s billion congressional and the PhP earner on a daily Php 446.00 wage Army (NPA) members at Bandong 1.3 –PhP 1.5 trillion presidential plus the recent paltry increase of Hill, Aguid, Sagada province. pork barrel is obvious. BS Aquino’s PhP22 a day; the farmers remain On August 29, two M520 and Huey helicopters of the Philippine stake on the pork barrel is not only landless, the urban poor homeless. Air Force hovered around northern the stability of his rule but also the It is appalling that the BS Sagada and upland Bontoc areas the preservation of the same rotten Aquino-led bureaucrats in the whole day, while the Sagada PNP system that coddles him and his government rob the people, in the conducted foot patrol in the outskirts real bosses – the hacienderos, the guise of serving the people; the of Sagada. -

Population by Barangay National Capital Region

CITATION : Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population Report No. 1 – A NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay August 2016 ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 1 – A 2015 Census of Population Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 Philippine Statistics Authority TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword v Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 vii List of Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Explanatory Text xiii Map of the National Capital Region (NCR) xxi Highlights of the Philippine Population xxiii Highlights of the Population : National Capital Region (NCR) xxvii Summary Tables Table A. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates for the Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities: 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxi Table B. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates by Province, City, and Municipality in National Capital Region (NCR): 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxiv Table C. Total Population, Household Population, -

Inequality of Opportunities Among Ethnic Groups in the Philippines Celia M

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Inequality of Opportunities Among Ethnic Groups in the Philippines Celia M. Reyes, Christian D. Mina and Ronina D. Asis DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2017-42 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are being circulated in a limited number of copies only for purposes of soliciting comments and suggestions for further refinements. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. December 2017 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Department, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 18th Floor, Three Cyberpod Centris – North Tower, EDSA corner Quezon Avenue, 1100 Quezon City, Philippines Tel Nos: (63-2) 3721291 and 3721292; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at https://www.pids.gov.ph Inequality of opportunities among ethnic groups in the Philippines Celia M. Reyes, Christian D. Mina and Ronina D. Asis. Abstract This paper contributes to the scant body of literature on inequalities among and within ethnic groups in the Philippines by examining both the vertical and horizontal measures in terms of opportunities in accessing basic services such as education, electricity, safe water, and sanitation. The study also provides a glimpse of the patterns of inequality in Mindanao. The results show that there are significant inequalities in opportunities in accessing basic services within and among ethnic groups in the Philippines. -

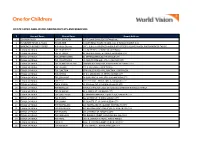

Top 100 Stockholders As of June 30, 2011

BPI STOCK TRANSFER OFFICE MANCHESTER INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS UNLIMITED CORP. TOP 100 STOCKHOLDERS AS OF JUNE 30, 2011 RANK STOCKHOLDER NUMBER STOCKHOLDER NAME NATIONALITY CERTIFICATE CLASS OUTSTANDING SHARES PERCENTAGE TOTAL 1 09002935 INTERPHARMA HOLDINGS & MANAGEMENT CORPORATION FIL A 255,264,483 61.9476% 255,264,483 C/O INTERPHIL LABORATORIES INC KM. 21 SOUTH SUPERHIGHWAY 1702 SUKAT, MUNTINLUPA, M. M. 2 1600000001 PHARMA INDUSTRIES HOLDINGS LIMITED BRT B 128,208,993 31.1138% 128,208,993 C/O ZUELLIG BUILDING, SEN. GIL J. PUYAT AVENUE, MAKATI CITY 3 16015506 PCD NOMINEE CORPORATION (FILIPINO) FIL A 10,969,921 G/F MKSE. BLDG, 6767 AYALA AVE MAKATI CITY B 8,258,342 4.6663% 19,228,263 4 16009811 PAULINO G. PE FIL A 181,250 29 NORTH AVENUE, DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY B 575,000 0.1835% 756,250 5 10002652 KASIGOD V. JAMIAS FIL A 464,517 109 APITONG ST., AYALA ALABANG MUNTINLUPA, METRO MANILA B 106,344 0.1385% 570,861 6 16011629 PCD NOMINEE CORPORATION (NON-FILIPINO) NOF B 393,750 0.0955% 393,750 G/F MKSE BUILDING 6767 AYALA AVENUE MAKATI CITY 7 16010090 PUA YOK BING FIL A 375,000 0.0910% 375,000 509 SEN. GIL PUYAT AVE. EXT. NORTH FORBES PARK MAKATI CITY 8 16009868 PAULINO G. PE FIL B 240,000 0.0582% 240,000 29 NORTH AVENUE, DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY 9 03030057 ROBERT S. CHUA FIL A 228,750 0.0555% 228,750 C/O BEN LINE, G/F VELCO CENTER R.S. OCA ST. COR. A.C. DELGADO PORT AREA, MANILA 10 03015970 JOSE CUISIA FIL A 187,500 0.0455% 187,500 C/O PHILAMLIFE INSURANCE CO. -

China's Intentions

Dealing with China in a Globalized World: Some Concerns and Considerations Published by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. 2020 5/F Cambridge Center Bldg., 108 Tordesillas cor. Gallardo Sts., Salcedo Village, Makati City 1227 Philippines www.kas.de/philippines [email protected] Cover page image, design, and typesetting by Kriselle de Leon Printed in the Philippines Printed with fnancial support from the German Federal Government. © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., 2020 The views expressed in the contributions to this publication are those of the individual authors and do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung or of the organizations with which the authors are afliated. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. Edited by Marie Antoinette P. de Jesus eISBN: 978-621-96332-1-5 In Memory of Dr. Aileen San Pablo Baviera Table of contents i Foreword • Stefan Jost 7 1 Globality and Its Adversaries in the 21st Century • Xuewu Gu 9 Globality: A new epochal phenomenon of the 21st century 9 Understanding the conditional and spatial referentiality of globality 11 Globality and its local origins 12 Is globality measurable? 13 Dangerous adversaries of globality 15 Conclusion 18 2 China’s Intentions: A Historical Perspective • Kerry Brown 23 Getting the parameters right: What China are we talking about and in which way? 23 Contrasting -

Briefing Paper on Business and Human Rights 2020

Source: The Guardian Briefing Paper on INTRODUCTION The Indigenous Peoples of Asia are Indigenous Peoples occupy lands rich Business and high up on the list of targets and in natural resources (waters, forests victims of human rights violations. and minerals) that are valuable for Killings, enforced disappearances, business operations. However, their Human Rights arbitrary arrest and detention, rights, including to their lands, intimidation, persecution and territories and resources and Free, 2020 violence against Indigenous Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), Peoples, Indigenous women and are very often not recognized and/or effectively implemented in business BHR SITUATION OF INDIGENOUS human rights defenders are PEOPLES IN ASIA increasing, even during this COVID- contexts. Laws, plans and activities 19 pandemic period. This trend of related to business and development Indigenous Peoples rights violations (narrowly understood as economic is expected to worsen as the growth) are mostly designed and implemented without meaningful An Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact government continues to centralize and consolidate its powers and participation of Indigenous Peoples, Report, November 2020 pursues its neoliberal economic particularly Indigenous women, even development program. when those laws and projects directly affect them. www.aippnet.org | 1 These result in profoundly negative human rights impacts, Secure governance systems coordinate voluntary including forced evictions/resettlements and loss of lands, isolation and community quarantines which are resources and livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples. When capable of maintaining Indigenous Peoples safe. In indigenous communities fight back, they face extreme these incidents, the right to FPIC is key as a community reprisals and risks, such as harassments, attacks, in involuntary isolation, to protect their community disappearances, violence against women and killings of from a virus must have been seen as withholding Indigenous leaders and human rights defenders. -

REGISTERED SHIPBUILDING and SHIP REPAIR ENTITY with FACILITIES, MANPOWER & CAPITALIZATION in CENTRAL OFFICE (As of DECEMBER 2019)

REGISTERED SHIPBUILDING AND SHIP REPAIR ENTITY WITH FACILITIES, MANPOWER & CAPITALIZATION IN CENTRAL OFFICE (as of DECEMBER 2019) CATEGORY/ LICENSED EQUITY MODE OF FACILITIES MANPOWER No. COMPANY CONTACT PERSON CLASSIFI- VALIDITY PARTICIPATION ACQUISITION GRAVING BUILDING FLOATING SLIPWAY/ TECHNICAL SKILLED SYNCHROLIFT CATION FIL (%) FORGN (%) OWNED LEASED DOCK YARD DOCK LAUNCHWAY PERM'T CONT'L PERM'T CONT'L 1 HERMA SHIPYARD INC. Engr. ROMMEL S. PERALTA A Sep 13, 2023 100% - - 15,000 GT 19,840 m 2 1,600 GT - 120 x 20 m 11 13 49 340 Herma Industrial Complex Yard Service Manager (154.50 x 31 (60.96 x Mariveles, Bataan herma.com.ph BATAAN BASECO JOINT x 12.20 m) 19.51 m) VESTURE, INC. Tel No. 047-9354368 Jun 26 2000 to Jun 25 2025 (25 yrs) 2 KEPPEL SUBIC SHIPYARD, INC. Ms. DINAH LABTINGAO A Sep 28, 2020 0.05% 99.95% OWNED - 550,000 170,000 m 2 - Gantry 300 x 65 m 33 10 119 290 Special Economic Zone, Cabangaan Accounting Manager DWT (shipyard area) Crane Pt., Cawag, Subic, Zambales [email protected] (1,500 tons) Tel No. 047-2322380 3 SUBIC DRYDOCK CORPORATION Mr. THOMAS J. PETRUCCI A Oct 02, 2020 99.80% 0.20 % - - 29,143 m 2 18,000 DWT - - 7 - 28 - Bldg. 17 Gridley cor. Schley Roads General Manager (american) 4,000 DWT SBMA SRF Cmpd., Subic Bay Freeport [email protected] Jun 20 2010 to Feb 20 2021 Zone Tel No. 047-2528183/ (11 yrs) 85/89 4 DANSYCO MARINE WORKS & Mr. DARY SY B Apr 02, 2019 100% - - - 1,800 m 2 - - High Blocks 5 - 48 - SHIPBUILDING CORP. -

11 SEPTEMBER 2020, FRIDAY Headline STRATEGIC September 11, 2020 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 2 Opinion Page Feature Article

11 SEPTEMBER 2020, FRIDAY Headline STRATEGIC September 11, 2020 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 2 Opinion Page Feature Article Cimatu aims to increase the width of Manila Bay beach Published September 10, 2020, 7:55 PM by Ellayn De Vera-Ruiz Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Secretary Roy Cimatu said beach nourishment in Manila Bay may help increase the width of the beaches as they are “very narrow.” Environment Secretary Roy A. Cimatu (RTVM / MANILA BULLETIN) This was part of the DENR’s response to a letter sent by the office of Manila Mayor Isko Moreno last Sept. 7, seeking the agency’s clarification on the safety of dolomite to public health. In his response dated Sept. 8, Cimatu pointed out that beach nourishment is the practice of adding sand or sediment to beaches to combat erosion and increase beach width. Beach nourishment, he explained, should be applied in Manila Bay because “Manila Bay is not considered prone to coastal erosion as it is mostly protected by seawalls, but the beaches are very narrow.” He cited that under the writ of continuing Mandamus issued by the Supreme Court on Dec. 18, 2016, a marching order was given to 13 government agencies, including the DENR to spearhead the clean up, rehabilitation, and preservation of Manila Bay “to make it more suitable for swimming, skin diving, and other forms of contact recreation and for protection of coastal communities.” “After dredging and clean up of the Bay, it was agreed upon by members of the different agencies involved in the rehabilitation of Manila Bay that the initial beach nourishment in Manila Bay will be applied in segment between the area fronting the US Embassy and the Manila Yacht Club to mimic a sort of a ‘pocket beach,’ the northern portion protected by the compound of the US Embassy and the south side sheltered by the Mall of Asia compound,” the letter read. -

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

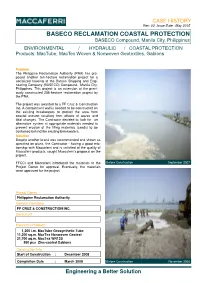

CH-CP-PH-BASECO Reclamation Coastal Protection with Mactube

CASE HISTORY Rev: 02, Issue Date : May 2015 BASECO RECLAMATION COASTAL PROTECTION BASECO Compound, Manila City, Philippines ENVIRONMENTAL / HYDRAULIC / COASTAL PROTECTION Products: MacTube, MacTex Woven & Nonwoven Geotextiles, Gabions Problem The Philippine Reclamation Authority (PRA) has pro- posed another ten-hectare reclamation project for a socialized housing at the Bataan Shipping and Engi- neering Company (BASECO) Compound, Manila City, Philippines. This project is an extension of the previ- ously constructed 256-hectare reclamation project by the PRA. The project was awarded to a FF Cruz & Construction Inc. A containment wall is needed to be constructed on the existing breakwaters to protect the area from coastal erosion resulting from effects of waves and tidal changes. The Contractor decided to look for an alternative system of appropriate materials needed to prevent erosion of the filling materials (sands) to be contained behind the existing breakwaters. Solution Despite another brand was recommended and shown as specified on plans, the Contractor - having a good rela- tionship with Maccaferri and is satisfied of the quality of Maccaferri products, sought Maccaferri’s proposal on the project. FFCCI and Maccaferri introduced the materials to the Before Construction September 2007 Project Owner for approval. Eventually, the materials were approved for the project. Project Owner Philippine Reclamation Authority General Contractor FF CRUZ & CONSTRUCTION INC. Consultant Maccaferri Products 1,200 l.m. MacTube Geosynthetic Tube 11,200 sq.m. MacTex Nonwoven Geotext 21,700 sq.m. MacTex WR12S 950 pcs Zinc-coated Gabions Construction Info Start of Construction : December 2008 Completion Date : March 2009 Before Construction November 2008 Engineering a Better Solution BASECO RECLAMATION COASTAL PROTECTION BASECO Compound, Manila City, Philippines Project Cross Section During Construction December 2008 MACCAFERRI (PHILIPPINES), INC.