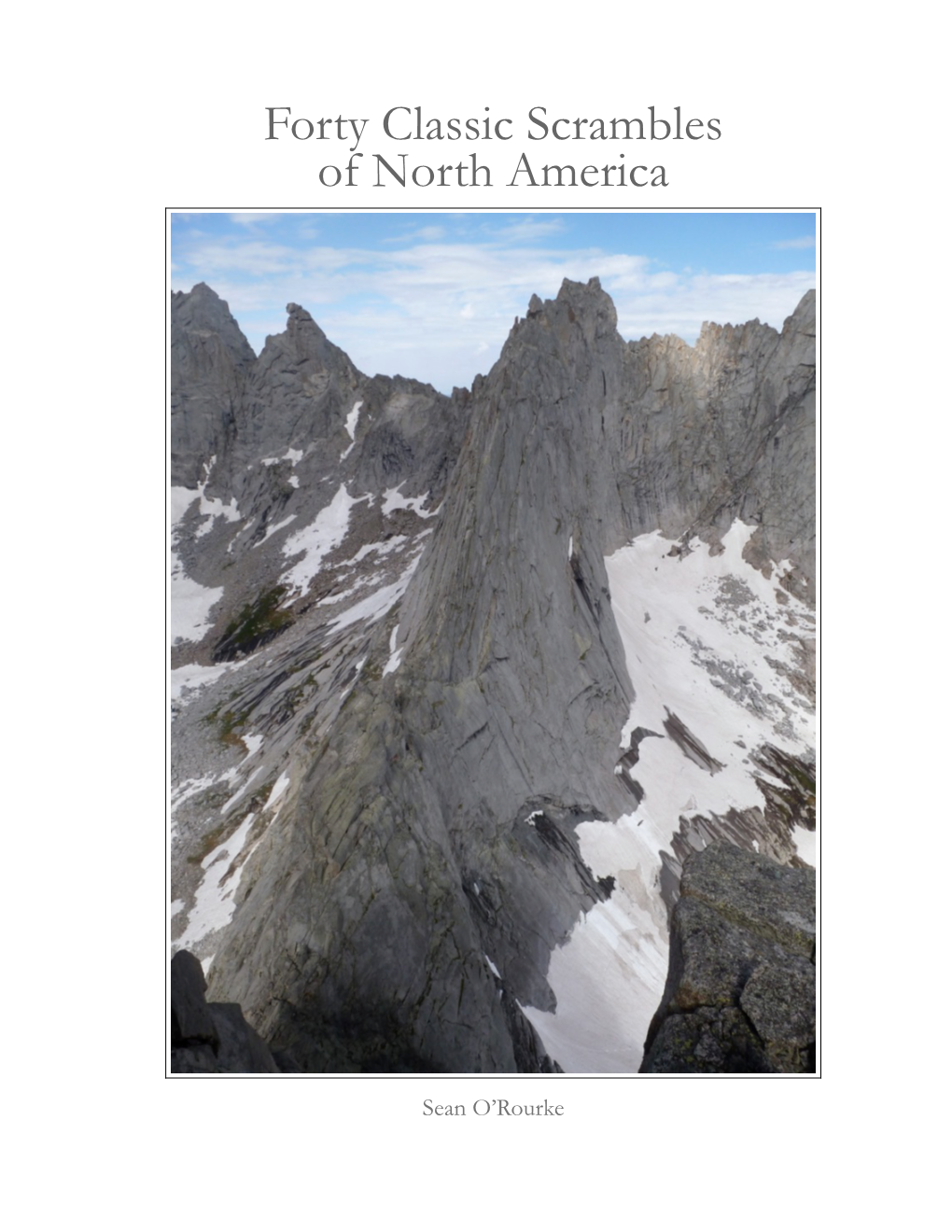

Forty Classic Scrambles of North America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARK 0 1 5 Kilometers S Ri South Entrance Road Closed from Early November to Mid-May 0 1 5 Miles G Ra River S Access Sy

To West Thumb North Fa r ll ve YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK 0 1 5 Kilometers s Ri South Entrance Road closed from early November to mid-May 0 1 5 Miles G ra River s access sy ad Grassy Lake L nch Ro a g Ra Reservoir k lag e F - Lake of Flagg Ranch Information Station R n the Woods to o Road not recommended 1 h a Headwaters Lodge & Cabins at Flagg Ranch s d for trailers or RVs. Trailhead A Closed in winter River G r lade C e access re e v k i R SS ERNE CARIBOU-TARGHEE ILD Glade Creek e r W Trailhead k Rive ITH a Falls n 8mi SM S NATIONAL FOREST 13km H Indian Lake IA JOHN D. ROCKEF ELLER, JR. D E D E J To South Bo C Pinyon Peak Ashton one C o reek MEMORIAL PARKWAY u 9705ft lt er Creek Steamboat eek Cr Mountain 7872ft Survey Peak 9277ft 89 C a n erry re B ek o z 191 i 287 r A C o y B o a t il e eek ey r C C r l e w e O Lizard C k r k Creek e e e re k C k e e r m C ri g il ly P z z ri G Jackson Lake North Bitch Overlook Cre ek GRAND BRIDGER-TETON NATIONAL FOREST N O ANY k B C ee EB Cr TETON WILDERNESS W Moose Arizona Island Arizona 16mi Lake k e 26km e r C S ON TETON NY o A u C t TER h OL C im IDAHO r B ilg it P ch Moose Mountain rk Pacic Creek k WYOMING Fo e Pilgrim e C 10054ft Cr re e Mountain t k s 8274ft Ea c Leeks Marina ci a P MOOSE BASIN NATIONAL Park Boundary Ranger Peak 11355ft Colter Bay Village W A k T e E N e TW RF YO r O ALLS CAN C O Colter Bay CE m A ri N g Grand View Visitor Center il L PARK P A Point KE 4 7586ft Talus Lake Cygnet Two Ocean 2 Pond Eagles Rest Peak ay Lake Trailhead B Swan 11258ft er lt Lake o Rolling Thunder -

Leo Grillmair Leo Grillmair

A Life So Fascinating: A Life So Fascinating: Leo Grillmair Leo Grillmair From poor and weary post-WWII Europe to the wild and free mountain wilderness of western Canada, Leo Grillmair’s life story is one of terrific adventure. Arriving in Canada from Austria in 1951, Grillmair and his life-long friend and business partner Hans Gmoser seized on the opportunities their newly-adopted country presented them and introduced Canadians to a whole new way of climbing rock faces. Brimming with optimism and industriousness, Grillmair applied an unwavering work ethic to help build a seasonal ski touring business to a 10-lodge helicopter skiing empire, which changed the face of backcountry recreation in the western hemisphere. As manager of Bugaboo Lodge, the world’s first heli- skiing lodge, in the world’s first and still largest helicopter skiing company, Canadian Mountain Holidays, Grillmair was instrumental in nurturing an entire industry that continues to employ hundreds of mountain guides, cooks, housekeepers, maintenance workers, pilots, engineers, massage therapists and numerous other office and lodge staff every year. Plumber, climbing pioneer, novice lumberjack, skier, professional rock collector, mountain guide, first-aid whiz, lodge manager, singer and storyteller extraordinaire, Leo Grillmair’s life is the stuff of which great stories are born. The Alpine Club of Canada is proud to celebrate its 20th Mountain Guides Ball with Leo Grillmair as Patron. For further information regarding The Summit Series of mountaineering biographies, please contact the National Office of the Alpine Club of Canada. www.AlpineClubofCanada.ca by Lynn Eleventh in the SUMMIT SERIES Biographies of people who have made a difference in Canadian Mountaineering. -

Anagement Plan

M ANAGEMENT LAN P March, 1999 11991998 for Bugaboo Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Provincial Park BC Parks Division Bugaboo Provincial Park M ANAGEMENT LAN P Prepared by BC Parks Kootenay District Wasa BC V0B 2K0 Bugaboo Provincial Park Management Plan Approved by: Wayne Stetski Date:99.12.01 Wayne Stetski District Manager Denis O’Gorman Date: 99.03.18 Denis O'Gorman Assistant Deputy Minister Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data BC Parks. Kootenay District Bugaboo Provincial Park management plan Cover title: Management plan for Bugaboo Provincial Park. ISBN 0-7726-3902-7 1. Bugaboo Provincial Park (B.C.) 2. Parks - British Columbia - Planning. 3. Parks - British Columbia - Management. I. Title. II. Title: Management plan for Bugaboo Provincial Park. FC3815.B83B32 1999333.78’3’0971165C99-960184-9 F1089.B83B32 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Plan Highlights ........................................................................................................1 Introduction.............................................................................................................3 The Management Planning Process ..........................................................................3 Background Summary.............................................................................................4 Planning Issues ........................................................................................................7 Relationship to Other Land Use Planning................................................................10 Role of the -

Jackson Hole Vacation Planner Vacation Hole Jackson Guide’S Guide Guide’S Globe Addition Guide Guide’S Guide’S Guide Guide’S

TTypefypefaceace “Skirt” “Skirt” lightlight w weighteight GlobeGlobe Addition Addition Book Spine Book Spine Guide’s Guide’s Guide’s Guide Guide’s Guide Guide Guide Guide’sGuide’s GuideGuide™™ Jackson Hole Vacation Planner Jackson Hole Vacation2016 Planner EDITION 2016 EDITION Typeface “Skirt” light weight Globe Addition Book Spine Guide’s Guide’s Guide Guide Guide’s Guide™ Jackson Hole Vacation Planner 2016 EDITION Welcome! Jackson Hole was recognized as an outdoor paradise by the native Americans that first explored the area thousands of years before the first white mountain men stumbled upon the valley. These lucky first inhabitants were here to hunt, fish, trap and explore the rugged terrain and enjoy the abundance of natural resources. As the early white explorers trapped, hunted and mapped the region, it didn’t take long before word got out and tourism in Jackson Hole was born. Urbanites from the eastern cities made their way to this remote corner of northwest Wyoming to enjoy the impressive vistas and bounty of fish and game in the name of sport. These travelers needed guides to the area and the first trappers stepped in to fill the niche. Over time dude ranches were built to house and feed the guests in addition to roads, trails and passes through the mountains. With time newer outdoor pursuits were being realized including rafting, climbing and skiing. Today Jackson Hole is home to two of the world’s most famous national parks, world class skiing, hiking, fishing, climbing, horseback riding, snowmobiling and wildlife viewing all in a place that has been carefully protected allowing guests today to enjoy the abundance experienced by the earliest explorers. -

Explorez Les Rocheuses Canadiennes Comprend Un Index

Symboles utilisés dans ce guide Jasper P Lake Louise Aussi disponibles dans la ip e s to n e et ses environs Classification des attraits touristiques p R r i collection o v « explorez » m e r e N À ne pas manquer Vaut le détour Intéressant n ««« «« « a de B d Whitehorn o es w G Mountain R l a i c les rocheuses canadiennes v Le label Ulysse r i Parc national Yoho e e r r s Chacun des établissements et activités décrits dans ce guide s’y retrouve en raison de ses qualités et particularités. Le label Ulysse indique ceux qui se distinguent parmi ce 93 Le meilleur pour vos découvertes! groupe déjà sélect. Lake Louise 1 Ski Resort les Mud Lake rocheuses Classification de l’hébergement Classification des restaurants 1 18 palmarès thématiques, L’échelle utilisée donne des indications L’échelle utilisée dans ce guide donne de prix pour une chambre standard des indications de prix pour un repas pour le meilleur des Rocheuses pour deux personnes, avant taxe, en complet pour une personne, avant les canadiennes vigueur durant la haute saison. boissons, les taxes et le pourboire. Lake canadiennes B Louise o $ moins de 75$ $ moins de 20$ Fairmont Chateau w V Lake Louise a 8 itinéraires clés en main 75$ à 100$ 20$ à 30$ lle $$ $$ y canadiennes P Lake a Le meilleur pour vos découvertes! rk $$$ 101$ à 150$ $$$ 31$ à 45$ Agnes w pour ne rien manquer et vivre des a Lake y $$$$ 151$ à 250$ $$$$ plus de 45$ Louise expériences inoubliables $$$$$ plus de 250$ 1A Tous les prix mentionnés dans ce guide sont en dollars canadiens. -

Grand Teton National Park Youngest Range in the Rockies

GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK YOUNGEST RANGE IN THE ROCKIES the town of Moran. Others recognized that dudes winter better than cows and began operating dude ranches. The JY and the Bar BC were established in 1908 and 1912, respectively. By the 1920s, dude ranch- ing made significant contributions to the valley’s economy. At this time some local residents real- ized that scenery and wildlife (especially elk) were valuable resources to be conserved rather than exploited. Evolution of a Dream The birth of present-day Grand Teton National Park involved controversy and a struggle that lasted several decades. Animosity toward expanding governmental control and a perceived loss of individual freedoms fueled anti-park senti- ments in Jackson Hole that nearly derailed estab- lishment of the park. By contrast, Yellowstone National Park benefited from an expedient and near universal agreement for its creation in 1872. The world's first national park took only two years from idea to reality; however Grand Teton National Park evolved through a burdensome process requiring three separate governmental Mt. Moran. National Park Service Photo. acts and a series of compromises: The original Grand Teton National Park, set Towering more than a mile above the valley of dazzled fur traders. Although evidence is incon- aside by an act of Congress in 1929, included Jackson Hole, the Grand Teton rises to 13,770 clusive, John Colter probably explored the area in only the Teton Range and six glacial lakes at the feet. Twelve Teton peaks reach above 12,000 feet 1808. By the 1820s, mountain men followed base of the mountains. -

Saddlebrooke Hiking Club Hike Database 11-15-2020 Hike Location Hike Rating Hike Name Hike Description

SaddleBrooke Hiking Club Hike Database 11-15-2020 Hike Location Hike Rating Hike Name Hike Description AZ Trail B Arizona Trail: Alamo Canyon This passage begins at a point west of the White Canyon Wilderness on the Tonto (Passage 17) National Forest boundary about 0.6 miles due east of Ajax Peak. From here the trail heads west and north for about 1.5 miles, eventually dropping into a two- track road and drainage. Follow the drainage north for about 100 feet until it turns left (west) via the rocky drainage and follow this rocky two-track for approximately 150 feet. At this point there is new signage installed leading north (uphill) to a saddle. This is a newly constructed trail which passes through the saddle and leads downhill across a rugged and lush hillside, eventually arriving at FR4. After crossing FR4, the trail continues west and turns north as you work your way toward Picketpost Mountain. The trail will continue north and eventually wraps around to the west side of Picketpost and somewhat paralleling Alamo Canyon drainage until reaching the Picketpost Trailhead. Hike 13.6 miles; trailhead elevations 3471 feet south and 2399 feet north; net elevation change 1371 feet; accumulated gains 1214 northward and 2707 feet southward; RTD __ miles (dirt). AZ Trail A Arizona Trail: Babbitt Ranch This passage begins just east of the Cedar Ranch area where FR 417 and FR (Passage 35) 9008A intersect. From here the route follows a pipeline road north to the Tub Ranch Camp. The route continues towards the corrals (east of the buildings). -

Harvard Mountaineering 3

HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING 1931·1932 THE HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING CLUB CAMBRIDGE, MASS. ~I I ' HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING 1931-1932 THE HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING CLUB CAMBRIDGE, MASS . THE ASCENT OF MOUNT FAIRWEATHER by ALLEN CARPE We were returning from the expedition to Mount Logan in 1925. Homeward bound, our ship throbbed lazily across the Gulf of Alaska toward Cape Spencer. Between reefs of low fog we saw the frozen monolith of St. Elias, rising as it were sheer out of the water, its foothills and the plain of the Malaspina Glacier hidden behind the visible sphere of the sea. Clouds shrouded the heights of the Fairweather Range as we entered Icy Strait and touched at Port Althorp for a cargo of salmon; but I felt then the challenge of this peak which was now perhaps the outstanding un climbed mOUlitain in America, lower but steeper than St. Elias, and standing closer to tidewater than any other summit of comparable height in the world. Dr. William Sargent Ladd proved a kindred spirit, and in the early summer of 1926 We two, with Andrew Taylor, made an attempt on the mountain. Favored by exceptional weather, we reached a height of 9,000 feet but turned back Photo by Bradford Washburn when a great cleft intervened between the but tresses we had climbed and the northwest ridge Mount Fairweather from the Coast Range at 2000 feet of the peak. Our base was Lituya Bay, a beau (Arrows mark 5000 and 9000-foot camps) tiful harbor twenty miles below Cape Fair- s camp at the base of the south face of Mount Fair weather; we were able to land near the foot of the r weather, at 5,000 feet. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

2018 Inaugural Hike

Spring/Summer 2018 2018 Inaugural Hike L-R: Cindy Bower, John Eastlake, Dan Wolfe, John Zimmer, Penny Weinhold, John Halter, Doug Wetherbee, Tom Fitzgerald, Jayne Fitzgerald, Larry Holtzapple, Bill Boyd, Wayne Baumann Photo by Curt Weinhold Dyer Farm Hike The original mission of the CCC camp was to begin con- struction of a new state park to be called the Black Forest A Civilian Conservation Corps Hike State Park. But when it was realized that Ole Bull State By Tom Fitzgerald, John Eastlake, and Penny Weinhold Park was only a few miles away, the mission of the camp Eleven members and two guests of the Susquehannock was changed to providing access for wildfire fighting, Trail Club gathered at the intersection of PA Route 44 and through the construction of roads and trails. Upon com- the Potter/Lycoming county line on the morning of Tues- pletion of its revised mission, the camp was closed on De- day, May 8, 2018. STC member John Eastlake, who spe- cember 15, 1937. cializes in the history of the Civilian conservation Corps (CCC) in Pennsylvania, led the group through part of the The tour began with a short drive to the Dyer Farm where area occupied by CCC Camp S-135 located near the south- we parked the vehicles at what we believe was the camp eastern corner of Stewardson Township, Potter County. headquarters building. The building is a log cabin with an unusual construction style. The outside walls of the build- The camp was established June 11, 1933 on the grounds of ing are made of short sections of small American chestnut an abandoned farm once occupied by a family named logs stacked up vertically end to end. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks

S o k u To Bishop ee t Piute Pass Cr h F 11423ft p o o 3482m r h k s S i o B u B i th G s h L o A p Pavilion Dome Mount C F 11846ft IE Goethe C or r R e k S 3611m I 13264ft a D VID e n 4024m k E J Lake oa q Sabrina u McClure Meadow k r i n 9600ft o F 2926m e l d R d Mount Henry i i Mount v 12196ft e Darwin M 3717m r The Hermit 13830ft South L 12360ft 4215m E 3767m Lake Big Pine C G 3985ft DINKEY O O 1215m O P D Hell for Sure Pass E w o N D Mount V s 11297ft A O e t T R McGee n L LAKES 3443m D U s E 12969ft T 3953m I O C C o A N r N Mount Powell WILDERNESS r D B a Y A JOHN l 13361ft I O S V I R N N 4072m Bi Bishop Pass g P k i ine Cree v I D e 11972ft r E 3649m C Mount Goddard L r E MUIR e 13568ft Muir Pass e C DUSY North Palisade k 4136m 11955ft O BASIN 3644m N 14242ft Black Giant T E 4341m 13330ft COURTRIGHT JOHN MUIR P Le Conte A WILDERNESS 4063m RESERVOIR L I Canyon S B Charybdis A 395 8720ft i D rc 13091ft E Middle Palisade h 2658m Mount Reinstein 14040ft 3990m C r WILDERNESS CR Cre e 12604ft A ek v ES 4279m i Blackcap 3842m N T R Mountain Y O an INYO d s E 11559ft P N N a g c r i 3523m C ui T f n M rail i i H c John K A e isad Creek C N Pal r W T e E s H G D t o D I T d E T E d V r WISHON G a a IL O r O S i d l RESERVOIR R C Mather Pass Split Mountain G R W Finger Pe ak A Amphitheater 14058ft E 12100ft G 12404ft S Lake 4285m 3688m E 3781m D N U IV P S I C P D E r E e R e k B C A SIERRA NATIONAL FOREST E art Taboose r S id G g k e I N Pass r k Tunemah Peak V D o e I 11894ft 11400ft F e A R r C 3625m ree 3475m C k L W n L k O Striped