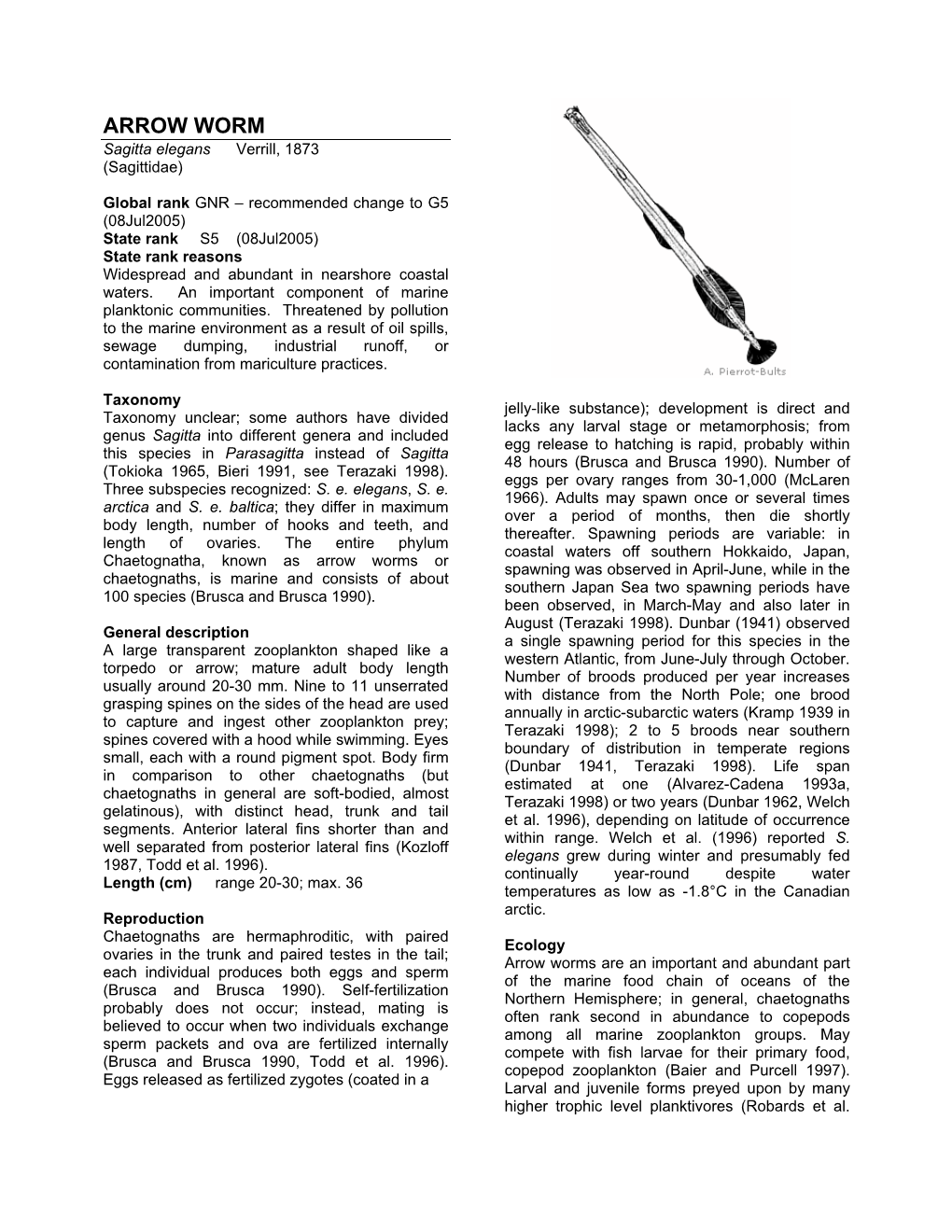

Species Description

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Lophophorates" Brachiopoda Echinodermata Asterozoa

Deuterostomes Bryozoa Phoronida "lophophorates" Brachiopoda Echinodermata Asterozoa Stelleroidea Asteroidea Ophiuroidea Echinozoa Holothuroidea Echinoidea Crinozoa Crinoidea Chaetognatha (arrow worms) Hemichordata (acorn worms) Chordata Urochordata (sea squirt) Cephalochordata (amphioxoius) Vertebrata PHYLUM CHAETOGNATHA (70 spp) Arrow worms Fossils from the Cambrium Carnivorous - link between small phytoplankton and larger zooplankton (1-15 cm long) Pharyngeal gill pores No notochord Peculiar origin for mesoderm (not strictly enterocoelous) Uncertain relationship with echinoderms PHYLUM HEMICHORDATA (120 spp) Acorn worms Pharyngeal gill pores No notochord (Stomochord cartilaginous and once thought homologous w/notochord) Tornaria larvae very similar to asteroidea Bipinnaria larvae CLASS ENTEROPNEUSTA (acorn worms) Marine, bottom dwellers CLASS PTEROBRANCHIA Colonial, sessile, filter feeding, tube dwellers Small (1-2 mm), "U" shaped gut, no gill slits PHYLUM CHORDATA Body segmented Axial notochord Dorsal hollow nerve chord Paired gill slits Post anal tail SUBPHYLUM UROCHORDATA Marine, sessile Body covered in a cellulose tunic ("Tunicates") Filter feeder (» 200 L/day) - perforated pharnx adapted for filtering & repiration Pharyngeal basket contractable - squirts water when exposed at low tide Hermaphrodites Tadpole larvae w/chordate characteristics (neoteny) CLASS ASCIDIACEA (sea squirt/tunicate - sessile) No excretory system Open circulatory system (can reverse blood flow) Endostyle - (homologous to thyroid of vertebrates) ciliated groove -

Abstract Book

January 21-25, 2013 Alaska Marine Science Symposium hotel captain cook & Dena’ina center • anchorage, alaska Bill Rome Glenn Aronmits Hansen Kira Ross McElwee ShowcaSing ocean reSearch in the arctic ocean, Bering Sea, and gulf of alaSka alaskamarinescience.org Glenn Aronmits Index This Index follows the chronological order of the 2013 AMSS Keynote and Plenary speakers Poster presentations follow and are in first author alphabetical order according to subtopic, within their LME category Editor: Janet Duffy-Anderson Organization: Crystal Benson-Carlough Abstract Review Committee: Carrie Eischens (Chair), George Hart, Scott Pegau, Danielle Dickson, Janet Duffy-Anderson, Thomas Van Pelt, Francis Wiese, Warren Horowitz, Marilyn Sigman, Darcy Dugan, Cynthia Suchman, Molly McCammon, Rosa Meehan, Robin Dublin, Heather McCarty Cover Design: Eric Cline Produced by: NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center / North Pacific Research Board Printed by: NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, Washington www.alaskamarinescience.org i ii Welcome and Keynotes Monday January 21 Keynotes Cynthia Opening Remarks & Welcome 1:30 – 2:30 Suchman 2:30 – 3:00 Jeremy Mathis Preparing for the Challenges of Ocean Acidification In Alaska 30 Testing the Invasion Process: Survival, Dispersal, Genetic Jessica Miller Characterization, and Attenuation of Marine Biota on the 2011 31 3:00 – 3:30 Japanese Tsunami Marine Debris Field 3:30 – 4:00 Edward Farley Chinook Salmon and the Marine Environment 32 4:00 – 4:30 Judith Connor Technologies for Ocean Studies 33 EVENING POSTER -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

The Plankton Lifeform Extraction Tool: a Digital Tool to Increase The

Discussions https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2021-171 Earth System Preprint. Discussion started: 21 July 2021 Science c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Open Access Open Data The Plankton Lifeform Extraction Tool: A digital tool to increase the discoverability and usability of plankton time-series data Clare Ostle1*, Kevin Paxman1, Carolyn A. Graves2, Mathew Arnold1, Felipe Artigas3, Angus Atkinson4, Anaïs Aubert5, Malcolm Baptie6, Beth Bear7, Jacob Bedford8, Michael Best9, Eileen 5 Bresnan10, Rachel Brittain1, Derek Broughton1, Alexandre Budria5,11, Kathryn Cook12, Michelle Devlin7, George Graham1, Nick Halliday1, Pierre Hélaouët1, Marie Johansen13, David G. Johns1, Dan Lear1, Margarita Machairopoulou10, April McKinney14, Adam Mellor14, Alex Milligan7, Sophie Pitois7, Isabelle Rombouts5, Cordula Scherer15, Paul Tett16, Claire Widdicombe4, and Abigail McQuatters-Gollop8 1 10 The Marine Biological Association (MBA), The Laboratory, Citadel Hill, Plymouth, PL1 2PB, UK. 2 Centre for Environment Fisheries and Aquacu∑lture Science (Cefas), Weymouth, UK. 3 Université du Littoral Côte d’Opale, Université de Lille, CNRS UMR 8187 LOG, Laboratoire d’Océanologie et de Géosciences, Wimereux, France. 4 Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Prospect Place, Plymouth, PL1 3DH, UK. 5 15 Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), CRESCO, 38 UMS Patrinat, Dinard, France. 6 Scottish Environment Protection Agency, Angus Smith Building, Maxim 6, Parklands Avenue, Eurocentral, Holytown, North Lanarkshire ML1 4WQ, UK. 7 Centre for Environment Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), Lowestoft, UK. 8 Marine Conservation Research Group, University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth, PL4 8AA, UK. 9 20 The Environment Agency, Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Peterborough, PE4 6HL, UK. 10 Marine Scotland Science, Marine Laboratory, 375 Victoria Road, Aberdeen, AB11 9DB, UK. -

Sagitta Siamensis, a New Benthoplanktonic Chaetognatha Living in Marine Meadows of the Andaman Sea, Thailand

Cah. Biol. Mar. (1997) 38 : 51-58 Sagitta siamensis, a new benthoplanktonic Chaetognatha living in marine meadows of the Andaman Sea, Thailand Jean-Paul Casanova (1) and Taichiro Goto(2) (1) Laboratoire de Biologie animale (Plancton), Université de Provence, Place Victor Hugo, 13331 Marseille Cedex 3, France Fax : (33) 4 91 10 60 06; E-mail: [email protected] (2) Department of Biology, Faculty of Education, Mie University, Tsu, Mie 514, Japan Abstract: A new benthoplanktonic chaetognath, Sagitta siamensis, is described from near-shore waters of Phuket Island (Thailand), in the Andaman Sea, where it lives among submerged vegetation. It is related to the species of the "hispida" group. In the laboratory, specimens have been observed swimming in the sea water but also sometimes adhering to the wall of the jars, and the eggs are benthic and attached on the substratum. Their fins are particularly thick and provided with clusters of probably adhesive cells on their ventral side and edges. This is the first mention of such fins in the genus Sagitta but the adhesive apparatus do not resemble that found in the benthic family Spadellidae and is less evolved. A review of the morphological characteristics of the species of the "hispida" group is done as well as their biogeography. Résumé : Un nouveau chaetognathe benthoplanctonique, Sagitta siamensis, est décrit des eaux néritiques de l'île Phuket (Thaïlande) en mer des Andaman, où il vit dans la végétation immergée. Il est proche des espèces du groupe "hispida". Au Laboratoire, les spécimens ont été observés nageant dans l'eau mais parfois aussi adhérant aux parois des récipients et les œufs sont benthiques, fixés sur le substratum. -

Check List of Plankton of the Northern Red Sea

Pakistan Journal of Marine Sciences, Vol. 9(1& 2), 61-78,2000. CHECK LIST OF PLANKTON OF THE NORTHERN RED SEA Zeinab M. El-Sherif and Sawsan M. Aboul Ezz National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Kayet Bay, Alexandria, Egypt. ABSTRACT: Qualitative estimation of phytoplankton and zooplankton of the northern Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba were carried out from four sites: Sharm El-Sheikh, Taba, Hurghada and Safaga. A total of 106 species and varieties of phytoplankton were identified including 41 diatoms, 53 dinoflagellates, 10 cyanophytes and 2 chlorophytes. The highest number of species was recorded at Sharm El-Sheikh (46 spp), followed by Safaga (40 spp), Taba (30 spp), and Hurghada (23 spp). About 95 of the recorded species were previously mentioned by different authors in the Red Sea and Gulf of Suez. Eleven species are considered new to the Red Sea. About 115 species of zooplankton were recorded from the different sites. They were dominated by four main phyla namely: Arthropoda, Protozoa, Mollusca, and Urochordata. Sharm El-Sheikh contributed the highest number of species (91) followed by Safaga (47) and Taba (34). Hurghada contributed the least (26). Copepoda dominated the other groups at the four sites. The appearances of Spirulina platensis, Pediastrum simplex, and Oscillatoria spp. of phyto plankton in addition to the rotifer species and the protozoan Difflugia oblongata of zooplankton impart a characteristic feature of inland freshwater discharge due to wastewater dumping at sea in these regions resulting from the expansion of cities and hotels along the coast. KEY WORDS: Plankton, Northern Red Sea, Check list. -

Chaetognatha: a Phylum of Uncertain Affinity Allison Katter, Elizabeth Moshier, Leslie Schwartz

Chaetognatha: A Phylum of Uncertain Affinity Allison Katter, Elizabeth Moshier, Leslie Schwartz What are Chaetognaths? Chaetognaths are in a separate Phylum by themselves (~100 species). They are carnivorous marine invertebrates ranging in size from 2-120 mm. There are also known as “Arrow worms,” “Glass worms,” and “Tigers of the zooplankton.” Characterized by a slender transparent body, relatively large caudal fins, and anterior spines on either side of the mouth, these voracious meat-eaters catch large numbers of copepods, swallowing them whole. Their torpedo-like body shape allows them to move quickly through the water, and the large spines around their mouth helps them grab and restrain their prey. Chaetognaths alternate between swimming and floating. The fins along their body are not used to swim, but rather to help them float. A Phylogenetic mystery: The affinities of the chaetognaths have long been debated, and present day workers are far from reaching any consensus of opinion. Problems arise because of the lack of morphological and physiological diversity within the group. In addition, no unambiguous chaetognaths are preserved as fossils, so nothing about this groups evolutionary origins can be learned from the fossil record. During the past 100 years, many attempts have been made to ally the arrow worms to a bewildering variety of taxa. Proposed relatives have included nematodes, mollusks, various arthropods, rotifers, and chordates. Our objective is to analyze the current views regarding “arrow worm” phylogeny and best place them in the invertebrate cladogram of life. Phylogeny Based on Embryology and Ultrastructure Casanova (1987) discusses the possibility that the Hyman, Ducret, and Ghirardelli have concluded chaetognaths are derived from within the mollusks. -

Polish Polar Res. 4-17.Indd

vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 459–484, 2017 doi: 10.1515/popore-2017-0023 Characterisation of large zooplankton sampled with two different gears during midwinter in Rijpfjorden, Svalbard Katarzyna BŁACHOWIAK-SAMOŁYK1*, Adrian ZWOLICKI2, Clare N. WEBSTER3, Rafał BOEHNKE1, Marcin WICHOROWSKI1, Anette WOLD4 and Luiza BIELECKA5 1 Institute of Oceanology Polish Academy of Sciences, Powstańców Warszawy 55, 81-712 Sopot, Poland 2 University of Gdańsk, Department of Vertebrate Ecology and Zoology, Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland 3 Pelagic Ecology Research Group, Scottish Oceans Institute, University of St Andrews, KY16 8LB, St Andrews, UK 4 Norwegian Polar Institute, Framsenteret, 9296 Tromsø, Norway 5 Department of Marine Ecosystems Functioning, Faculty of Oceanography and Geography, Institute of Oceanography, University of Gdańsk, Al. Marszałka Piłsudskiego 46, 81-378 Gdynia, Poland * corresponding author <[email protected]> Abstract: During a midwinter cruise north of 80oN to Rijpfjorden, Svalbard, the com- position and vertical distribution of the zooplankton community were studied using two different samplers 1) a vertically hauled multiple plankton sampler (MPS; mouth area 0.25 m², mesh size 200 μm) and 2) a horizontally towed Methot Isaacs Kidd trawl (MIK; mouth area 3.14 m², mesh size 1500 μm). Our results revealed substantially higher species diversity (49 taxa) than if a single sampler (MPS: 38 taxa, MIK: 28) had been used. The youngest stage present (CIII) of Calanus spp. (including C. finmarchi- cus and C. glacialis) was sampled exclusively by the MPS, and the frequency of CIV copepodites in MPS was double that than in MIK samples. In contrast, catches of the CV-CVI copepodites of Calanus spp. -

A Century of Monitoring Station Prince 6 in the St. Croix River Estuary of Passamaquoddy Bay

A century of monitoring station Prince 6 in the St. Croix River estuary of Passamaquoddy Bay by F. J. Fife, R. L. M. Goreham and F. H. Page A collaborative project involving Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment Canada, Passamaquoddy people, and Bay of Fundy Ecosystem Partnership June 8, Oceans Day, 2015 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Methods historical samples field.………………………………………………………………………..2 hydrographic sampling………………………………………………………………………...3 zooplankton samples…………………………………………………………………………...3 historical samples – laboratory………………………………………………………………...4 contemporary samples – field – hydrographic sampling………………………………………4 zooplankton sampling……………………………………….5 laboratory……………………………………………………………8 Results and discussion……………………………………………………………………………………9 variation in zooplankton counts by the two sorters……………………………………………9 hydrographic conditions – sea surface temperature…………………………………………..10 sea surface salinity………………………………………………..12 sea surface salinity and Atlantic hurricane time-line…………….14 biological conditions – diversity and life-history……………………………………………..19 diversity, density and phenology…………………………………….24 fine mesh vertical plankton tow monthly time series………………..24 setal feeders functional group…………………………………..26 mucous feeders………………………………………………….31 eggs………………………………………………………...…...36 larvae………………………………………………………..….40 type 1 predator……………………………………………..…...59 type 2 predator……………………………………………….....66 presence/absence overview for vertical plankton tow……..…..71 fine mesh subsurface plankton -

Life Cycle and Growth Rate of the Chaetognath Parasagitta Elegans in the Northern North Pacific Ocean

Plankton Biol. Ecol. 46 (2): 153-158, 1999 plankton biology & ecology •' The Plankton Society of J;ip;m I1)1)1) Life cycle and growth rate of the chaetognath Parasagitta elegans in the northern North Pacific Ocean MORIYUKI KOTORl Hokkaido Central Fisheries Experimental Station, Yoichi, Hokkaido 046-8555. Japan (e-mail: kotorim(«tfishexp.prcf.liokkaido.jp) Received 3 April 1998: accepted 17 December 1998 Abstract: Breeding periods and growth rate of the typical boreal epipelagic chaetognath Parasagitta elegans (Verrill) were investigated in the northwestern North Pacific off eastern Hokkaido. Seasonally, P. elegans were most abundant in the epipelagic layers in early June to October, while they were al ways poor in abundance during December to April. It is suggested that the decrease in abundance in early December was partly due to vertical migration into water deeper than 150 m in winter. The main breeding period of the chaetognath was observed in late May to early June. Some cohorts produced by the spawning populations were able to be traced at least until early December. Thus, the mean growth rate of the cohorts was estimated to be 0.03 to 0.29 mm d \ averaging approximately 0.1 mmd \ which corresponds to 3 mm month"1. This value is lower than that (5 to 6 mm month 1) re ported from the Gulf of Alaska, eastern North Pacific. Although the generation length of P. elegans is still uncertain in the present area, it is probably longer than that in the northeastern Pacific Ocean, being 1 year or possibly 2 years. This suggests that reproductive and high growth periods in P. -

Vertical Distribution and Seasonal Variation of Pelagic Chaetognaths in Sagami Bay, Central Japan

Plankton Benthos Res 7(2): 41–54, 2012 Plankton & Benthos Research © The Plankton Society of Japan Vertical distribution and seasonal variation of pelagic chaetognaths in Sagami Bay, central Japan 1,2, 2 2 1 HIROOMI MIYAMOTO *, SHUHEI NISHIDA , KAZUNORI KURODA & YUJI TANAKA 1 Graduate School of Marine Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, 4–5–7 Konan, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108–8477, Japan 2 Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, University of Tokyo, 5–1–5 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa, Chiba 277–8564, Japan Received 22 November 2011; Accepted 24 February 2012 Abstract: The vertical distribution and seasonal variation of pelagic chaetognaths was investigated in Sagami Bay, based on stratified zooplankton samples from the upper 1,400 m. The chaetognaths were most abundant in the 100– 150 m layer in January and May 2005, whereas they were concentrated in the upper 50 m in the other months. Among the 28 species identified, Zonosagitta nagae had the highest mean standing stock, followed by Flaccisagitta enflata and Eukrohnia hamata. Cluster analysis based on species composition and density separated chaetognath communi- ties into four groups (Groups A–D). While the distribution of Group C was unclear due to their rare occurrence, the other groups were more closely associated with depth than with season. The epipelagic group (Group A) was further divided into four sub-groups, which were related to seasonal hydrographic variation. The mesopelagic group (Group B) was mainly composed of samples from the 150–400 m layer, although Group A, in which the epipelagic species Z. nagae dominated, was distributed in this layer from May to July. -

Genetic Variation in the Planktonic Chaetognaths Parasagitta Elegans and Eukrohnia Hamata

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 101: 243-251,1993 Published November 25 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Genetic variation in the planktonic chaetognaths Parasagitta elegans and Eukrohnia hamata Erik V. Thuesen*,Ken-ichi Numachi, Takahisa Nemoto** Ocean Research Institute, University of Tokyo, 1-15-1 Minamidai, Nakano-ku, Tokyo 164, Japan ABSTRACT: Two species of planktonic chaetognaths, Parasagitta elegans (Verrill) and Eukrohnia hamata (Mobius), from waters off Japan were analyzed electrophoretically and found to display very low levels of genetic variabhty. Nineteen enzyme loci were examined for 7 population samples of P, elegans, and the proportion of polymorphic loci (P,,,,)and average frequency of heterozygotes per locus (H) were calculated as 0.11 and 0.026, respectively. Fifteen enzyme loci were examined for 2 populations of E. hamata, and and H were calculated as 0.10 and 0.038, respectively. On the basis of allele frequencies at 2 enzyme loci it is possible to suggest that P. elegans population samples col- lected in the Sea of Japan were reproductively isolated from those in the Oyashio. Moreover it would appear that 4 population samples of P. elegans in the Sea of Japan are representative of a panmictic population. Differences in allele frequencies between population samples of the Oyashio suggest that these populations are genetically structured. It appears that genetic structuring exists in the 2 popula- tion samples investigated for E. hamata also. P. elegans and E. hamata expressed no common alleles over all the loci assayed indicating that the 2 species are phylogenetically very distant within the phylum Chaetognatha. INTRODUCTION Ayala et al.