Natural History Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Microlepidopterous Fauna of Sri Lanka, Formerly Ceylon, Is Famous

ON A COLLECTION OF SOME FAMILIES OF MICRO- LEPIDOPTERA FROM SRI LANKA (CEYLON) by A. DIAKONOFF Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden With 65 text-figures and 18 plates CONTENTS Preface 3 Cochylidae 5 Tortricidae, Olethreutinae, Grapholitini 8 „ „ Eucosmini 23 „ „ Olethreutini 66 „ Chlidanotinae, Chlidanotini 78 „ „ Polyorthini 79 „ „ Hilarographini 81 „ „ Phricanthini 81 „ Tortricinae, Tortricini 83 „ „ Archipini 95 Brachodidae 98 Choreutidae 102 Carposinidae 103 Glyphipterigidae 108 A list of identified species no A list of collecting localities 114 Index of insect names 117 Index of latin plant names 122 PREFACE The microlepidopterous fauna of Sri Lanka, formerly Ceylon, is famous for its richness and variety, due, without doubt, to the diversified biotopes and landscapes of this beautiful island. In spite of this, there does not exist a survey of its fauna — except a single contribution, by Lord Walsingham, in Moore's "Lepidoptera of Ceylon", already almost a hundred years old, and a number of small papers and stray descriptions of new species, in various journals. The authors of these papers were Walker, Zeller, Lord Walsingham and a few other classics — until, starting with 1905, a flood of new descriptions 4 ZOOLOGISCHE VERHANDELINGEN I93 (1982) and records from India and Ceylon appeared, all by the hand of Edward Meyrick. He was almost the single specialist of these faunas, until his death in 1938. To this great Lepidopterist we chiefly owe our knowledge of all groups of Microlepidoptera of Sri Lanka. After his death this information stopped abruptly. In the later years great changes have taken place in the tropical countries. We are now facing, alas, the disastrously quick destruction of natural bio- topes, especially by the reckless liquidation of the tropical forests. -

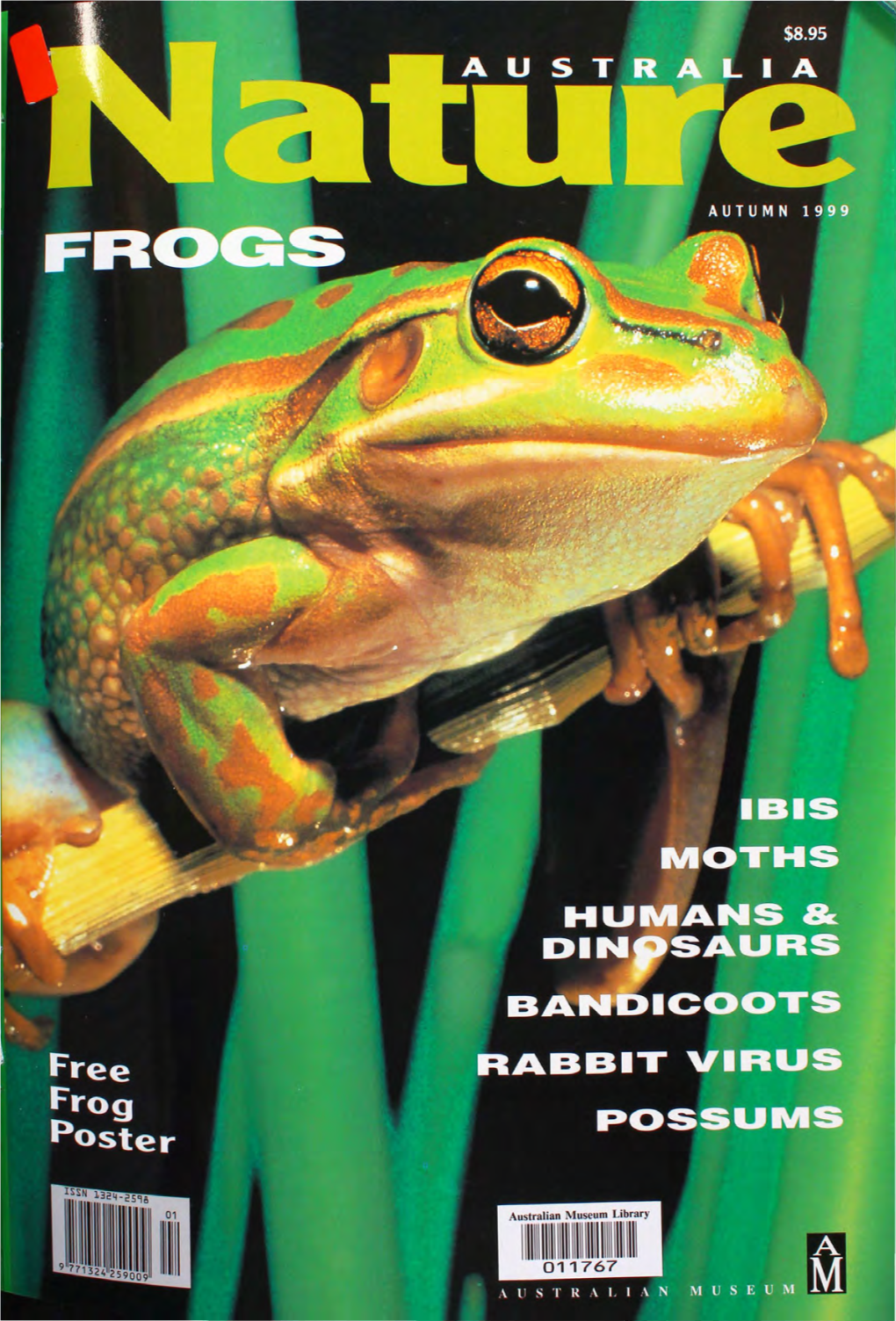

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

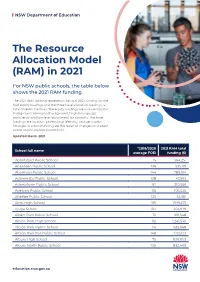

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

STATEMENT of CHAIRMAN AJIT PAI Re: Advanced Methods to Target and Eliminate Unlawful Robocalls, CG Docket No. 17-59. During

STATEMENT OF CHAIRMAN AJIT PAI Re: Advanced Methods to Target and Eliminate Unlawful Robocalls, CG Docket No. 17-59. During the final season of Seinfeld, Elaine gets a new phone number that used to belong to her recently deceased elderly neighbor. She soon begins receiving up to six calls a day from the neighbor’s grandson, who’s looking for his Gammy. Elaine quickly gets fed up and breaks the news to him: “Good- bye, Bobby. Don’t call anymore. I’m dead now. Gotta go.”1 Unfortunately, many consumers share this frustration over getting repeated calls intended for someone else. This is especially true in the case of robocalls to reassigned numbers. Today, when you change your phone number, you probably don’t notify everyone who’s called you in the past, including businesses to which you’ve given permission to call. So when your old number is reassigned, the new holder of that number may get calls intended for you. These misdirected calls are a nuisance to the consumers that receive them. And at the same time, legitimate businesses, through no fault of their own, waste their time and effort calling the wrong consumers while subjecting themselves to potential liability under the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA). What can the FCC do to tackle this reassigned numbers problem? As the D.C. Circuit unanimously recognized last week,2 we’ve been exploring ways to reduce unwanted robocalls to reassigned numbers. And today, we take another step toward developing a solution. Specifically, we propose to ensure that businesses have access to one or more databases that contain the comprehensive and timely information they need to avoid calling reassigned numbers. -

Second Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Federal Communications Commission FCC 18-31 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Advanced Methods to Target and Eliminate ) CG Docket No. 17-59 Unlawful Robocalls ) SECOND FURTHER NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING Adopted: March 22, 2018 Released: March 23, 2018 Comment Date: (45 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) Reply Comment Date: (75 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) By the Commission: Chairman Pai and Commissioners Clyburn, O’Rielly, and Carr issuing separate statements; Commissioner Rosenworcel approving in part, dissenting in part, and issuing a statement. I. INTRODUCTION 1. In this Second Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, as part of our multiple-front battle against unwanted calls, we propose and seek comment on ways to address the problem of unwanted calls to reassigned numbers. This problem subjects the recipient of the reassigned number to annoyance and wastes the time and effort of the caller while potentially subjecting the caller to liability. 2. Consumer groups and callers alike have asked for a solution to this problem. We therefore propose to ensure that one or more databases are available to provide callers with the comprehensive and timely information they need to discover potential number reassignments before making a call. To that end, we seek further comment on, among other issues: (1) the specific information that callers need from a reassigned numbers database; and (2) the best way to make that information available to callers that want it. Making a reassigned numbers database available to callers that want it will benefit consumers by reducing unwanted calls intended for another consumer while helping callers avoid the costs of calling the wrong consumer, including potential violations of the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA).1 II. -

1 Production Information in Just Go with It, a Plastic Surgeon

Production Information In Just Go With It, a plastic surgeon, romancing a much younger schoolteacher, enlists his loyal assistant to pretend to be his soon to be ex-wife, in order to cover up a careless lie. When more lies backfire, the assistant's kids become involved, and everyone heads off for a weekend in Hawaii that will change all their lives. Columbia Pictures presents a Happy Madison production, Just Go With It. Starring Adam Sandler and Jennifer Aniston. Directed by Dennis Dugan. Produced by Adam Sandler, Jack Giarraputo, and Heather Parry. Screenplay by Allan Loeb and Timothy Dowling. Based on ―Cactus Flower,‖ Screenplay by I.A.L. Diamond, Stage Play by Abe Burrows, Based upon a French Play by Barillet and Gredy. Executive Producers are Barry Bernardi, Allen Covert, Tim Herlihy, and Steve Koren. Director of Photography is Theo Van de Sande, ASC. Production Designer is Perry Andelin Blake. Editor is Tom Costain. Costume Designer is Ellen Lutter. Music by Rupert Gregson-Williams. Music Supervision by Michael Dilbeck, Brooks Arthur, and Kevin Grady. Just Go With It has been rated PG-13 by the Motion Picture Association of America for Frequent Crude and Sexual Content, Partial Nudity, Brief Drug References and Language. The film will be released in theaters nationwide on February 11, 2011. 1 ABOUT THE FILM At the center of Just Go With It is an everyday guy who has let a careless lie get away from him. ―At the beginning of the movie, my character, Danny, was going to get married, but he gets his heart broken,‖ says Adam Sandler. -

Issues Paper for the Grey Nurse Shark (Carcharias Taurus)

Issues Paper for the Grey Nurse Shark (Carcharias taurus) 2014 The recovery plan linked to this issues paper is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/resource/recovery-plan-grey-nurse-shark-carcharias-taurus © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Department of the Environment, Public Affairs, GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 or email [email protected]. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Cover images by Justin Gilligan Photography Contents List of figures ii List of tables ii Abbreviations ii 1 Summary 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 Purpose 2 2.2 Objectives 2 2.3 Scope 3 2.4 Sources of information 3 2.5 Recovery planning process 3 3 Biology and ecology 4 3.1 Species description 4 3.2 Life history 4 3.3 Diet 5 3.4 Distribution 5 3.5 Aggregation sites 8 3.6 Localised movements at aggregation sites 10 3.7 Migratory movements -

Sydney Program Guide

6/19/2020 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_ELEVEN_Guide?psStartDate=05-Jul-20&psEndDate=11-… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 05th July 2020 06:00 am Toasted TV G Toasted TV Sunday 2020 163 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:05 am Dora The Explorer (Rpt) G Baby Bongo's Big Music Show Dora and Boots take Baby Bongo on a musical adventure as they race to the Big Music Show in time for Baby Bongo's first performance. 06:25 am Toasted TV G Toasted TV Sunday 2020 164 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:30 am Blaze And The Monster Machine (Rpt) G The Jungle Horn Stripes loves his jungle horn, a special instrument that can summon all the animals in the jungle, but when a jealous Crusher steals it, Blaze & Stripes must speed after him in a chase to get it back. 06:55 am Toasted TV G Toasted TV Sunday 2020 165 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:00 am The Bureau Of Magical Things (Rpt) CC G Forces Of Attraction Ruksy, Imogen and Lily venture into the dangerous Restricted Section of the Library in search of the truth about Kyra's new magical powers. -

Matters of National Environmental Significance Report

Gold Coast Quarry EIS ATTACHMENT D SITE ACCESS PLANS September 2013 Cardno Chenoweth 99 Gold Coast Quarry EIS ATTACHMENT E SITE TOPOGRAPHY September 2013 Cardno Chenoweth 99 Pacific Motorway 176 176 RP899491 RP899491 N 6889750 m E 539000 m E 539250 m E 539500 m E 539750 m E 540000 m E 540250 m E 540500 m E 540750 m E 541000 m E 541250 m E 541500 m N 6889750 m 903 905 SP210678 SP245339 144 905 WD4736 SP245339 N 6889500 m N 6889500 m Old Coach Road 22 SP238363 N 6889250 m N 6889250 m N 6889000 m N 6889000 m 103 105 5 SP127528 SP144215 RP162129 Barden Ridge Road 103 SP127528 Chesterfield Drive N 6888750 m N 6888750 m 1 RP106195 4 RP162129 RP853810 RP162129 927 6 4 5 SP220598 RP853810 3 RP854351 RP162129 2 N 6888500 m 5 N 6888500 m RP803474 SP105668 12 WD6568 SP105668 7 11 1 SP187063 105 2 3 F:\Jobs\1400\1454 Cardno Boral_Tallebudgera GCQ\000 Generic\Drawings\1454_017 Topography_aerial.dwg 15 SP144215 RP812114 RP803474 RP903701 1 Tallebudgera Creek Road 3 RP148506 FILE NAME: 13 RP803474 SP105668 901 RP907357 2 3 RP803474 SP187063 RP164840 6 N 6888250 m N 6888250 m 14 SP105668 600 SP251058 3 JOB SUB #: 901 1 SP145343 RP205290 RP148504 2 27 Samuel Drive 104 RP811199 RP190638 RP180320 2 8 October 2012 30 2 RP180320 SP150481 N 6888000 m RP838498 31 N 6888000 m RP180321 E 539000 m E 539250 m E 539500 m E 539750 m E 540000 m E 540250 m E 540500 m E 540750 m E 541000 m E 541250 m E 541500 m CREATED: REV DESCRIPTION DATE BY Legend: PROJECT: TITLE: Site Boundary Tallebudgera Figure 13 - Aerial Photo and Topography Photography: Nearmap. -

Montague Island Seabird Habitat Restoration Project

Montague Island Seabird Habitat Restoration Project Proceedings of Shared Island Management Workshop Narooma, NSW, November 2008 Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW Cover photos clockwise from left: www.geoffcomfort.com; S. Cohen, DECCW; S. Donaldson; DECCW. Inset bird: DECCW Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney PO Box A290, Sydney South 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978 1 74232 337 4 DECCW 2009/443 November 2009 Printed on environmentally sustainable stock B Contents Preface ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1 Overview -

NESTING of the SOOTY SHEARWATER in AUSTRALIA the First Recorded Breeding of the Sooty Shearwater Al

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS NESTING OF THE SOOTY SHEARWATER IN AUSTRALIA The first recorded breeding of the Sooty Shearwater al. (1971) who listed Little Witch Island (Flat Witch Puffinus griseus in Australia was reported by Rohu Island in the Maatsuyker Group), Flat (Mutton Bird) (1914). He collected a specimen and "eggs" on 29 Island, Breaksea Island and Green (Hobbs) Island as December 1912 on Broughton Island, NSW. A check of breeding stations; these locations were published on in- the H.L. White Collection in the National Museum, formation received from C. Pitt, a former Surveyor- Melbourne, revealed that a "clutch of one egg ..." was General and Secretary for Lands in Tasmania, in March collected. Since that first report a number of published 1947. Pizzey (1980) also listed these locations except records have appeared; all refer to islands off New that he recorded Maatsuyker Island as the breeding sta- South Wales and Tasmania. tion apparently instead of Flat Witch Island in the Maatsuyker Group. No doubt his source of information In New South Wales, the Sooty Shearwater has also was that already published. been recorded breeding on Lion Island (Keast & McGill 1948), Little Broughton Island (Hindwood & D'Om- The additional locations supplied by Pitt all occur in brain 1960), Montague Island (Robinson 1964), Bird south-western Tasmania and, at the time of his report, Island (Lane 1965), Boondelbah Island (Morris et al. very little was known about the distribution of these 1973), Bowen Island (Lane 1975a), Tollgate Islands birds in this area. In those days, most reports originated (McKean & Fullagar 1976) and Cabbage Tree Island from fishermen, or lighthouse-keepers stationed on (Fullagar 1976).