Sources of Inspiration in Willa Cather's Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Willa Cather and American Arts Communities

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2004 At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jewell, Andrew W., "At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 15. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES by Andrew W. Jewel1 A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Susan J. Rosowski Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2004 DISSERTATION TITLE 1ather and Ameri.can Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewel 1 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Approved Date Susan J. Rosowski Typed Name f7 Signature Kenneth M. Price Typed Name Signature Susan Be1 asco Typed Name Typed Nnme -- Signature Typed Nnme Signature Typed Name GRADUATE COLLEGE AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES Andrew Wade Jewell, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2004 Adviser: Susan J. -

UNIVERSITY of $ASKATCHEWAN This Volume Is The

UNIVERSITY OF $ASKATCHEWAN This volume is the property of the University of Saskatchewan, and the Itt.rory rights of the author and of the University must be respected. If the reader ob tains any assistance from this volume, he must give proper credit in his ownworkr This Thesis by . EJi n.o r • C '.B • C j-IEJ- S0 M has been used by the following persons, whose slgnature~ attest their acc;eptance of the above restri ctions . Name and Address Date , UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN The Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Saskatchewan. We, the undersigned members of the Committee appointed by you to examine the Thesis submitted by Elinor C. B. Chelsom, B.A., B;Ed., in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts, beg to report that we consider the thesis satisfactory both in form and content. Subject of Thesis: ttWilla Cather And The Search For Identity" We also report that she has successfully passed an oral examination on the general field of the subject of the thesis. 14 April, 1966 WILLA CATHER AND THE SEARCH FOR IDENTITY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Mas ter of Arts in the Department of English University of Saskatchewan by Elinor C. B. Chelsom Saskatoon, Saskatchewan April, 1966 Copyrigh t , 1966 Elinor C. B. Chelsom IY 1 s 1986 1 gratefully acknowledge the wise and encouraging counsel of Carlyle King, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. my supervisor in the preparation of this thesis. -

Willa Cather Review

Copyright C 1997 by the Willa Cather Pioneer ISSN 0197-663X Memorial and Educational Foundation (The Willa Cather Society) Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial New-sletter and 326 N. Webster Street VOLUME XLI, No. 2 Red Cloud, Nebraska 68970 Summer/Fall, 1997 Review Telephone (402) 746-2653 The Little House and the Big Rock: So - what happened to me when I began to try to plan my paper for today was that my two projects Wilder, Cather, and refused to remain separate in my mind, and I had to the Problem of Frontier Girls envision a picture with a place for Willa Cather and Laura Ingalls Wilder. That meant I had to think about Plenary Address, new ways to historicize both careers. And that's why Sixth International Willa Cather Seminar I was so delighted to recognize the bit of information Quebec City, June 1995 with which I began. It places Wilder and Cather - Ann Romines who almost but not quite shared a publisher in 1931 - George Washington University in the same literary and cultural landscape. Women of about the same age with Midwestern childhoods far In August 1931, Alfred A. Knopf published Willa behind them, they were writing and publishing novels Cather's tenth novel, Shadows on the Rock. The publisher numbered Cather among the ''family" of authors he was proud to publish.1 Then, in the following month, Knopf contracted to publish the first book by a contemporary of Cather's, the children's novel Little House in the Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder. Be fore the year was out, however, Wilder learned that the exigencies of "depression economics" were closing down the children's department at Knopf. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscripthas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affectreproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sectionswith small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI .. A Bell & Howell mtorrnauon Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Getting Back to Their Texts: A Reconsideration of the Attitudes of Willa Cather and Hamlin Garland Toward Pioneer Li fe on the Midwestern Agricultural Frontier A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHJLOSOPHY IN ENGLISH AUGUST 1995 By Neil Gustafson Dissertation Committee: Mark K. -

Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory

Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory Edited by William E. Cain Professor of English Wellesley College A Routledge Series 94992-Humphries 1_24.indd 1 1/25/2006 4:42:08 PM Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory William E. Cain, General Editor Vital Contact Negotiating Copyright Downclassing Journeys in American Literature Authorship and the Discourse of from Herman Melville to Richard Wright Literary Property Rights in Patrick Chura Nineteenth-Century America Martin T. Buinicki Cosmopolitan Fictions Ethics, Politics, and Global Change in the “Foreign Bodies” Works of Kazuo Ishiguro, Michael Ondaatje, Trauma, Corporeality, and Textuality in Jamaica Kincaid, and J. M. Coetzee Contemporary American Culture Katherine Stanton Laura Di Prete Outsider Citizens Overheard Voices The Remaking of Postwar Identity in Wright, Address and Subjectivity in Postmodern Beauvoir, and Baldwin American Poetry Sarah Relyea Ann Keniston An Ethics of Becoming Museum Mediations Configurations of Feminine Subjectivity in Jane Reframing Ekphrasis in Contemporary Austen, Charlotte Brontë, and George Eliot American Poetry Sonjeong Cho Barbara K. Fischer Narrative Desire and Historical The Politics of Melancholy from Reparations Spenser to Milton A. S. Byatt, Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie Adam H. Kitzes Tim S. Gauthier Urban Revelations Nihilism and the Sublime Postmodern Images of Ruin in the American City, The (Hi)Story of a Difficult Relationship from 1790–1860 Romanticism to Postmodernism Donald J. McNutt Will Slocombe Postmodernism and Its Others Depression Glass The Fiction of Ishmael Reed, Kathy Acker, Documentary Photography and the Medium and Don DeLillo of the Camera Eye in Charles Reznikoff, Jeffrey Ebbesen George Oppen, and William Carlos Williams Monique Claire Vescia Different Dispatches Journalism in American Modernist Prose Fatal News David T. -

Troll Garden and Selected Stories

Troll Garden and Selected Stories Willa Cather The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Troll Garden and Selected Stories, by Willa Cather. Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. The Troll Garden and Selected Stories by Willa Cather. October, 1995 [Etext #346] The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Troll Garden and Selected Stories, by Willa Cather. *****This file should be named troll10.txt or troll10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, troll11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, troll10a.txt. This etext was created by Judith Boss, Omaha, Nebraska. The equipment: an IBM-compatible 486/50, a Hewlett-Packard ScanJet IIc flatbed scanner, and Calera Recognition Systems' M/600 Series Professional OCR software and RISC accelerator board donated by Calera Recognition Systems. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. Please note: neither this list nor its contents are final till midnight of the last day of the month of any such announcement. -

Examensarbete Faith Valdner

Linköping University Department of Culture and Communication English, Teachers’ Program Paradise Lost vs Paradise Regained: A Study of Childhood in Three Short Stories by Willa Cather Faith Valdner C Course: Literary Specialization Spring Term 2013 Supervisor: Helena Granlund Contents Introduction…………………………………………..………………………………………..3 Chapter I: “The Way of the World” – Paradise Lost ………………………………………….6 Chapter II: “The Enchanted Bluff” – Paradise Lost?…………………………………………13 Chapter III: “The Treasure of Far Island” – Paradise Regained ……………..…...………….18 Chapter IV: Cather’s Stories in the Classroom ………………...…….…..………..…………25 Conclusion………….……………………………………………………...……….………...30 Works Cited…………………………………………….……………...…………….……….32 2 Introduction Willa Cather is a much beloved and critically acclaimed author, awarded the 1923 Pulitzer Prize for one of her novels One of Ours (1922), yet her name has not been as celebrated as some of her contemporaries. As Eric McMillan points out: “Willa Cather is one of those quietly achieving American writers, whose works are quietly appreciated in the shadow of the era’s Great Writers … but going on a century later, are still being quietly appreciated when many of the once great ones are no longer read” (§1, 2013-05-02). From the time of the westward pioneering, America’s rise to world power, the Depression to the Second World War, Cather lived through the most significant time of American history. However, her works are centered on Nebraska and the American Southwest. She herself grew up in Nebraska, thus the pioneers and their lives in the area became a main source of inspiration to her. Cather had a strong emotional tie to her childhood and she seemed to think that childhood is the best years of a person’s life. -

Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Newsletter VOLUME XXXV, No

Copyright © 1992 by the Wills Cather Pioneer ISSN 0197-663X Memorial and.Educational Foundation Winter, 1991-92 Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Newsletter VOLUME XXXV, No. 4 Bibliographical Issue RED CLOUD, NEBRASKA Jim Farmer’s photo of the Hanover Bank and Trust in Johnstown, Nebraska, communicates the ambience of the historic town serving as winter locale for the Hallmark Hall of Fame/Lorimar version of O Pioneers.l, starring Jessica Lange. The CBS telecast is scheduled for Sunday 2 February at 8:00 p.m. |CST). A special screening of this Craig Anderson production previewed in Red Cloud on 18 January with Mr. Anderson as special guest. Board News Works on Cather 1990-1991" A Bibliographical Essay THE WCPM BOARD OF GOVERNORS VOTED UNANIMOUSLY AT THE ANNUAL SEPTEMBER Virgil Albertini MEETING TO ACCEPT THE RED CLOUD OPERA Northwest Missouri State University HOUSE AS A GIFT FROM OWNER FRANK MOR- The outpouring of criticism and scholarship on HART OF HASTINGS, NEBRASKA. The Board ac- Willa Cather definitely continues and shows signs of cepted this gift with the intention of restoring the increasing each year. In 1989-1990, fifty-four second floor auditorium to its former condition and articles, including the first six discussed below, and the significance it enjoyed in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Among the actresses who appeared on five books were devoted to Cather. In 1990-91, the its stage was Miss Willa Cather, who starred here as number increased to sixty-five articles, including the Merchant Father in a production of Beauty and those in four collections, and eight books. -

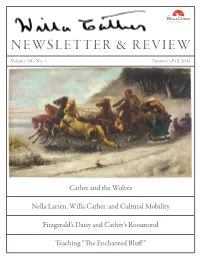

Newsletter & Review

NEWSLETTER & REVIEW Volume 58 z No. 1 Summer z Fall 2015 Cather and the Wolves Nella Larsen, Willa Cather, and Cultural Mobility Fitzgerald’s Daisy and Cather’s Rosamond Teaching “The Enchanted Bluff ” Willa Cather NEWSLETTER & REVIEW Volume 58 z No. 1 | Summer z Fall 2015 2 9 17 31 24 30 33 CONTENTS 1 Letters from the Executive Director and the President 17 More Than Beautiful Little Fools: Fitzgerald’s Daisy, Cather’s Rosamond, and Postwar Images of 2 “Never at an End”: The Search for Sources of Cather’s American Women z Mallory Boykin Wolves Story z Michela Schulthies 24 Upwardly Mobile: Teaching “The Enchanted Bluff ” 4 New Life for a Well-known Painting to Contemporary Students z Christine Hill Smith 5 Describing the Restoration z Kenneth Bé 30 New Beginnings for National Willa Cather Center 9 Meanings of Mobility in Willa Cather’s The Song of 31 In Memoriam: Charlene Hoschouer the Lark and Nella Larsen’s Quicksand Amy Doherty Mohr 33 Willa Cather and the Connection to Kyrgyzstan Max Despain On the cover: Sleigh with Trailing Wolves by Paul Powis. Photo courtesy of the Nebraska State Historical Society’s Gerald R. Ford Conservation Center. Letter from the City of Red Cloud, and the area Chamber of Commerce the Executive Director to further develop and enhance the visitor experience. Through Ashley Olson the hire of a Heritage Tourism Development Director, the partnership will increase Red Cloud’s appeal as a destination for tourists through creation of new services and amenities. Jarrod As I write this, a productive and busy summer at the Willa Cather McCartney, a scholar and Red Cloud native, has already settled Foundation is drawing to a close and we are celebrating the success of into this position comfortably. -

Children's Literature

BLACK HISTORY & LITERATURE WOMEN LITERATURE EARLY 2020 ONLINE CATALOGUE CHILDREN’S LITERATURE AMERICANA ART & ARCHITECTURE SCIENCE & MEDICINE ECONOMICS HISTORY, PHILOSOPHY & RELIGION TRAVEL & EXPLORATION PASTIMES Black History & Literature 2 ©2020 Bauman Rare Books www.baumanrarebooks.com 1-800-97-BAUMAN (1-800-972-2862) B B L “The First American Martyr To The A A Freedom Of The Press, And The Freedom U C Of The Slave” (John Quincy Adams) M K A (LOVEJOY, Elijah P.) LOVEJOY, Joseph C. and Owen. Memoir of the Rev. N H Elijah P. Lovejoy; Who Was Murdered in Defence of the Liberty of the I Press, At Alton, Illinois, Nov. 7, 1837. With an Introduction by John R S Quincy Adams. New York, 1838. Octavo, original gray cloth. $3200. A T R View on Website O E R First edition of the publisher and editor’s memoir, issued the year after his Y murder, only two years after he denounced the lynching by fire of a free B black man, as an act of “savage barbarity,” a seminal record of key event in O & America’s abolitionist battle and the history of the First Amendment. O K Elijah Lovejoy, who was born in Maine, began publishing the abolitionist Observer after L S he moved to St. Louis. When, in 1836, a mob dragged Francis McIntosh, a free black I man accused of murder, from the St. Louis jail and set him on fire, killing him, “Lovejoy’s T Observer described the lynching by fire as an ‘awful murder and savage barbarity’… [and] • E attacked Judge Luke Lawless” (St. -

Money in the Fiction of Willa Cather Vincent A

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 7-1974 Money in the Fiction of Willa Cather Vincent A. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Fiction Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Vincent A., "Money in the Fiction of Willa Cather" (1974). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 554. https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/554 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I,OMA LINDA UNIVERSITY Graduate School MONEY IN THE FICTION O'F WILL..~ CATHER by Vincent A. Clark ------·--- A Thesis in Partial Fulfillment Master of Arts in the Field of English .July 1974 Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this thesis in his opinion thesis for the degree Master of Arts. ;). ~~Delmar I. Davis, i)~cU'""""""-)~t-J.--"------Professor of _LvlJr IT". U~ -·--· -- Robert Pg Dunn 1 Associate Professor of English CONTENTS ., .L. Introduction 1 2. Money in the Life of Willa Cather 8 3. The Early Books . 16 4. The Pioneer Triumphant • . 25 5. Mammon and the Modern World 40 6. The Days That Are No More . 71 7. Conclusion: Money in the Fiction of Willa Cather .• 80 Notes ... -

3122298.PDF (5.565Mb)

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ANTIMODERN STRATEGIES: AMBIVALENCE, ACCOMMODATION, AND PROTEST IN WILLA CATHER’S THE TROLL GARDEN A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By STEPHANIE STRINGER GROSS Norman, Oklahoma 2004 UMI Number: 3122298 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3122298 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ©Copyright by STEPHANIE STRINGER GROSS 2004 All Rights Reserved. ANTIMODERN STRATEGIES: AMBIVALENCE, ACCOMMODATION, AND PROTEST IN WILLA CATHER’S THE TROLL GARDEN A Dissertation APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Dr. Ronald Schleifer, Director Dr. William HenrYiMcDonald )r. Francesca Savraya Dr. Melissa/I. Homestead Dr. Robert Griswold ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project would never have been completed without the many hours of discussions with members of my committee, Professors Henry McDonald, Melissa Homestead, Francesca Sawaya, and Robert Griswold, and especially Professor Ronald Schleifer, and their patience with various interminable drafts.