General Assembly Distr.: General 24 December 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal Preparedness for Regional and International Disaster Assistance in the Pacific Country Profiles

LEGAL PREPAREDNESS FOR REGIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL DISASTER ASSISTANCE IN THE PACIFIC COUNTRY PROFILES ifrc.org The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is the world’s largest volunteer-based humanitarian network, reaching 150 million people each year through our 192-member National Societies. Together, we act before, during and after disasters and health emergencies to meet the needs and improve the lives of vulnerable people. We do so with impartiality as to nationality, race, gender, religious beliefs, class and political opinions. Guided by Strategy 2020 and Strategy 2030 – our collective plan of action to tackle the major humanitarian and development challenges of this decade – we are committed to ‘saving lives and changing minds’. Our strength lies in our volunteer network, our community- based expertise and our independence and neutrality. We work to improve humanitarian standards, as partners in development and in response to disasters. We persuade decision-makers to act at all times in the interests of vulnerable people. The result: we enable healthy and safe communities, reduce vulnerabilities, strengthen resilience and foster a culture of peace around the world. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies © International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent P.O. Box 303 Societies, Asia Pacific Regional Office, Kuala Lumpur, 2020 CH-1211 Geneva 19, Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 730 4222 Any part of this publication may be cited, copied, translated Telefax: +41 22 733 0395 into other languages or adapted to meet local needs without E-mail: [email protected] prior permission from the International Federation of Red Cross Website: www.ifrc.org and Red Crescent Societies, provided that the source is clearly stated. -

South Pacific

South Pacific Governance in the Pacific: the dismissal of Tuvalu's Governor-General Tauaasa Taafaki BK 338.9 GRACE FILE BARCOOE ECO Research School of Pacific and Asian \\\\~ l\1\1 \ \Ul\\ \ \\IM\\\ \\ CBR000029409 9 Enquiries The Editor, Working Papers Economics Division Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra 0200 Australia Tel (61-6) 249 4700 Fax (61-6) 257 2886 ' . ' The Economics Division encompasses the Department of Economics, the National Centre for Development Studies and the Au.§.tralia-J.apan Research Centre from the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, the Australian National University. Its Working Paper series is intended for prompt distribution of research results. This distribution is preliminary work; work is later published in refereed professional journals or books. The Working Papers include V'{Ork produced by economists outside the Economics Division but completed in cooperation with researchers from the Division or using the facilities of the Division. Papers are subject to an anonymous review process. All papers are the responsibility of the authors, not the Economics Division. conomics Division Working Papers " South Pacific Governance in the Pacific: the dismissal of Tuvalu's Governor-General Tauaasa Taafaki / o:,;7 CJ<,~ \}f ftl1 L\S\\ltlR~ Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies C;j~••• © Economics Division, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, 1996. This work is copyright. Apart from those uses which may be permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 as amended, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. -

The Appointment, Tenure and Removal of Judges Under Commonwealth

The The Appointment, Tenure and Removal of Judges under Commonwealth Principles Appoin An independent, impartial and competent judiciary is essential to the rule tmen of law. This study considers the legal frameworks used to achieve this and examines trends in the 53 member states of the Commonwealth. It asks: t, Te ! who should appoint judges and by what process? nur The Appointment, Tenure ! what should be the duration of judicial tenure and how should judges’ remuneration be determined? e and and Removal of Judges ! what grounds justify the removal of a judge and who should carry out the necessary investigation and inquiries? Re mo under Commonwealth The study notes the increasing use of independent judicial appointment va commissions; the preference for permanent rather than fixed-term judicial l of Principles appointments; the fuller articulation of procedural safeguards necessary Judge to inquiries into judicial misconduct; and many other developments with implications for strengthening the rule of law. s A Compendium and Analysis under These findings form the basis for recommendations on best practice in giving effect to the Commonwealth Latimer House Principles (2003), the leading of Best Practice Commonwealth statement on the responsibilities and interactions of the three Co mmon main branches of government. we This research was commissioned by the Commonwealth Secretariat, and undertaken and alth produced independently by the Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. The Centre is part of the British Institute of International and -

A/HRC/39/8 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/39/8 General Assembly Distr.: General 10 July 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-ninth session 10–28 September 2018 Agenda item 6 Universal periodic review Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* Tuvalu * The annex is being circulated without formal editing, in the language of submission only. GE.18-11385(E) A/HRC/39/8 Introduction 1. The Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review, established in accordance with Human Rights Council resolution 5/1, held its thirtieth session from 7 to 18 May 2018. The review of Tuvalu was held at the 6th meeting, on 9 May 2018. The delegation of Tuvalu was headed by the Prime Minister of Tuvalu, Enele Sosene Sopoaga. At its 10th meeting, held on 11 May 2018, the Working Group adopted the report on Tuvalu. 2. On 10 January 2018, the Human Rights Council selected the following group of rapporteurs (troika) to facilitate the review of Tuvalu: Mexico, Mongolia and Senegal. 3. In accordance with paragraph 15 of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 5/1 and paragraph 5 of the annex to Council resolution 16/21, the following documents were issued for the review of Tuvalu: (a) A national report submitted/written presentation made in accordance with paragraph 15 (a) (A/HRC/WG.6/30/TUV/1); (b) A compilation prepared by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in accordance with paragraph 15 (b) (A/HRC/WG.6/30/TUV/2); (c) A summary prepared by OHCHR in accordance with paragraph 15 (c) (A/HRC/WG.6/30/TUV/3); 4. -

Study on Acquisition and Loss of Citizenship

COMPARATIVE REPORT 2020/01 COMPARATIVE FEBRUARY REGIONAL 2020 REPORT ON CITIZENSHIP LAW: OCEANIA AUTHORED BY ANNA DZIEDZIC © Anna Dziedzic, 2020 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Global Citizenship Observatory (GLOBALCIT) Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies in collaboration with Edinburgh University Law School Comparative Regional Report on Citizenship Law: Oceania RSCAS/GLOBALCIT-Comp 2020/1 February 2020 Anna Dziedzic, 2020 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes, projects and data sets, in addition to a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration, the expanding membership of the European Union, developments in Europe’s neighbourhood and the wider world. -

Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project

Annex VI (b) – Environmental and Social Management Plan GREEN CLIMATE FUND FUNDING PROPOSAL I Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project Environmental and Social Management Plan Annex VI (b) – Environmental and Social Management Plan GREEN CLIMATE FUND FUNDING PROPOSAL I Disclaimer This Environmental and Social Management Plan has been prepared for the submission of the proposal to the Green Climate Fund for the purposes of assisting in the assessment of the potential environmental and social impacts of the proposal. This Environmental and Social Management Plan has been prepared prior to undertaking an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment. Normally, an Environmental and Social Management Plan would be prepared following baseline studies and then the subsequent impact assessment contained within the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (or commonly known as an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA)) and would form the basis for the construction and operational environmental and social management plans. As no Environmental and Social Impact Assessment have been undertaken for the projects, this Environmental and Social Management Plan has been prepared solely on the author’s experience with projects of this nature and in consideration of international good practice for these types of projects. Accordingly, the Environmental and Social Management Plan will be subject to change following the preparation of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment/s. Assumptions The following assumptions have been made in the preparation of this Environmental and Social Management Plan: 1. all components of the proposal will have an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment/s prepared prior to the construction and operation of the specific project components; 2. none of the projects will require the displacement of people; 3. -

Law of Thesea

Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea Office of Legal Affairs Law of the Sea Bulletin No. 83 asdf United Nations New York, 2014 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Furthermore, publication in the Bulletin of information concerning developments relating to the law of the sea emanating from actions and decisions taken by States does not imply recognition by the United Nations of the validity of the actions and decisions in question. IF ANY MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THE BULLETIN IS REPRODUCED IN PART OR IN WHOLE, DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT SHOULD BE GIVEN. Copyright © United Nations, 2013 Page I. UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA ......................................................... 1 Status of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, of the Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the Convention and of the Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the Convention relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks ................................................................................................................ 1 1. Table recapitulating the status of the Convention and of the related Agreements, as at 30 November 2013 ................................................................................................................. 1 2. Chronological lists of ratifications of, accessions and successions to the Convention and the related Agreements, as at 30 November 2013 ................................................................................ 9 a. The Convention ....................................................................................................................... 9 b. -

Advancing Women's Political Participation in Tuvalu

REPORT 5 Advancing Women’s Political Participation in Tuvalu A Research Project Commissioned by the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS) By Susie Saitala Kofe and Fakavae Taomia Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible if it had not been for the tremendous support granted by the President of the Tuvalu National Council of Women Mrs Katalaina Malua, the Director of Women Affairs Mrs Saini Simona and the Executive Director of the Tuvalu Association of Non Governmental Organisations Mrs Annie Homasi. You have not only been there to provide the moral support that I greatly needed during the research process, but you have also assisted me greatly in your areas of expertise. Your wisdom and altruistic attitude gave me tremendous strength to complete this work and I am invaluably indebted to you. I also would like to thank the Honourable Speaker to Parliament Otinielu Tautele I Malae Tausi, Cabinet Ministers Hon Saufatu Sopoaga, Hon Samuelu Teo, Hon Leti Pelesala, Honorable Members of Parliament Hon Kokea Malua, Hon Elisala Pita, Hon Kausea Natano, Hon Tavau Teii and Hon Halo Tuavai for supporting this research by participating in the research process. Many thanks also to senior government officials for taking their valuable time to participate in the research. Not forgetting also the individual representatives from the civil society as well as the island communities for consenting to partici- pate in this research. Your invaluable contributions have made it possible for me to complete this work and I sincerely thank you all for your patience and efforts. Last and not least I thank my family and especially my husband for supporting me all the way. -

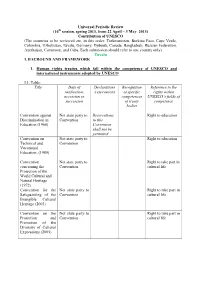

Universal Periodic Review (16 Session, Spring 2013, From

Universal Periodic Review (16 th session, spring 2013, from 22 April – 3 May 2013) Contribution of UNESCO (The countries to be reviewed are, in this order: Turkmenistan, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Colombia, Uzbekistan, Tuvalu, Germany, Djibouti, Canada, Bangladesh, Russian Federation, Azerbaijan, Cameroon, and Cuba. Each submission should refer to one country only) Tuvalu I. BACROUND AND FRAMEWORK 1. Human rights treaties which fall within the competence of UNESCO and international instruments adopted by UNESCO I.1. Table: Title Date of Declarations Recognition Reference to the ratification, /reservations of specific rights within accession or competences UNESCO’s fields of succession of treaty competence bodies Convention against Not state party to Reservations Right to education Discrimination in Convention to this Education (1960) Convention shall not be permitted Convention on Not state party to Right to education Technical and Convention Vocational Education. (1989) Convention Not state party to Right to take part in concerning the Convention cultural life Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972) Convention for the Not state party to Right to take part in Safeguarding of the Convention cultural life Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003) Convention on the Not state party to Right to take part in Protection and Convention cultural life Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005) 2 II. Promotion and protection of human rights on the ground Right to education Normative Framework: 2. Constitutional framework: Tuvalu has a constitutional monarchy. The British monarch is the titular head of state and represented by a Tuvaluan governor general. 1 The 1978 Constitution of Tuvalu 2 includes human rights guarantees but not specifically the right to education. -

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

United Nations CEDAW/C/TUV/2 Convention on the Elimination Distr.: General of All Forms of Discrimination 3 September 2008 against Women Original: English Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women Combined initial and second periodic reports of States parties Tuvalu* * The present report is being issued without formal editing. 08-49945 (E) 131108 *0849945* CEDAW/C/TUV/2 Contents Page Acronyms ....................................................................... 6 Glossary of Terms ................................................................ 7 Part I — Introduction ............................................................. 8 Tuvalu: The Land and the People.................................................... 8 Historical Background............................................................. 8 The Land ....................................................................... 8 The People ...................................................................... 9 Demography..................................................................... 11 Development Indicators ........................................................... 13 The Economy .................................................................... 14 Government Machinery............................................................ 16 The Situation and Advancement of Women........................................... -

Citizenship Act

CITIZENSHIP ACT 2008 Revised Edition CAP. 24.05 Citizenship Act CAP. 24.05 Arrangement of Sections CITIZENSHIP ACT Arrangement of Sections Section 1 Short title................................................................................................................ 5 2 Interpretation.......................................................................................................... 5 3 Register of Citizenship........................................................................................... 6 4 Citizenship Committee........................................................................................... 7 5 Citizenship by registration ..................................................................................... 8 6 Citizenship by naturalisation.................................................................................. 8 7 Loss of Tuvalu citizenship..................................................................................... 9 8 Renunciation of Tuvalu citizenship ..................................................................... 11 9 Regaining Tuvalu citizenship .............................................................................. 11 10 Renunciation of foreign citizenship in certain cases............................................ 11 11 Offences............................................................................................................... 12 12 Regulations ......................................................................................................... -

Small States & Territories, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2018, Pp. 35-54. Democratic

Small States & Territories, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2018, pp. 35-54. Democratic innovations and the challenges of parliamentary oversight in a small state: Is small really beautiful? Jack Corbett Department of Politics and International Relations University of Southampton, United Kingdom [email protected] Abstract: It is commonly asserted that, when it comes to democratic politics, ‘small is beautiful’. This assumption harks back to antiquity and is employed by advocates of participatory and deliberative democracy to justify innovations that ‘scale-down’ decision- making in large states. Despite their obvious relevance, this literature fails to account for the democratic experience of the world's smallest states. In this article, I bring small states in to this discussion by examining recent democratic innovations in Tuvalu. Rather than ‘scaling- down’, in this instance Tuvalu is attempting to ‘scale-up’ its democratic institutions due to the challenges posed by its small size. The lesson for advocates of decentralisation in large states and the orthodox view that ‘small is beautiful’ is a cautionary one: size matters but not necessarily in the manner democratic theory predicts or in ways that fulfil normative desires. Keywords: democratic governance, democratic innovations, parliamentary oversight, small states, Tuvalu, Pacific Islands © 2018: Islands and Small States Institute, University of Malta, Malta. Introduction As the tasks of the state have become more complex and the size of polities larger and more heterogeneous, the institutional forms of liberal democracy developed in the nineteenth century – representative democracy plus technocratic bureaucratic administration – seem increasingly ill suited to the novel problems we face in the twenty-first century (Fung and Wright, 2001, p.