The Status and Management of Moose in North America – Circa 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7.9 Vegetation 7.9.1 Regional Setting

VICTORY NICKEL INC. 7.9 Vegetation This subsection summarizes the 2007 and 2008 vegetation survey programs completed at and surrounding the Minago Project site. URS Canada Inc. (URS, 2008d) conducted a detailed vegetation survey on the Minago Project site in 2007 and Roche Consulting Group (Roche, 2008a) conducted a vegetation survey along a 24.4 km stretch on Highway 6, just south of the site’s main entrance and along a potential railway siding near Ponton, Manitoba. Prior to a detailed description of the vegetation survey methodology and results, characteristics of regional and local settings are summarized below in terms of ecozone and ecoregion. 7.9.1 Regional Setting – Ecozone Regionally, the Minago Project Site is located within the Boreal Plains ecozone (URS, 2008d). This ecozone is a wide band that extends from the Peace River area of northeast British Columbia to the southeast corner of Manitoba. This zone is located immediately south of and is distinctly different from the Boreal Shield ecozone, which is bedrock controlled. The Boreal Plains ecozone is not bedrock controlled and contains fewer lakes. The dominant coniferous species in this ecozone are white and black spruce, jack pine and tamarack. Deciduous species consist predominantly of white birch, trembling aspen and balsam poplar, particularly in transition zones to the prairie grasslands to the south. Black spruce and tamarack are more abundant along the northern transition zone to the Boreal Shield ecozone. 7.9.2 Local Setting – Ecoregion The Minago Project Area including the Site occupies approximately 2,428 hectares, west of Highway 6, and is located within the Mid-Boreal Lowland ecoregion of the northern section of the Manitoba Plain (URS, 2008d). -

The Ecology and Management of Moose in North America

THE ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF MOOSE IN NORTH AMERICA Douglas H. PIMLOTT Department of Lands and Forests, Maple, Ontario, Canada Concepts of the status, productivity and management of North American moose (Alces alces) have changed greatly during the past decade. The rapidity of the change is illustrated by the published record. TUFTS (1951) questioned, « Is the moose headed for extinc tion ? » and discussed the then current belief that moose populations had seriously declined across much of the continent. Five years later, PETERSON (1955: 217) stated, « It appears almost inevitable that the days of unlimited hunting for moose must soon pass from most of North America. » He also suggested (1955 : 216) that a kill of 12 to 25 per cent of the adult population is the highest that would permit the maintenance of the breeding population. Four years later, I showed (PIMLOTT, 1959a) that moose in Newfoundland could sustain a kill of twice the magnitude suggested by Peterson. I also suggested (PIMLOTT, 1959b) that the North American moose kill could be very greatly increased-in spite of progressive liberalization of hunting regulations over much of Canada and a marked increase in annual kill. It is not realistic to assume that the status of the species has changed, within the decade, from threatened extinction to annual harvests of approximately 40,000 and potential harvests of two to three times that number. Although moose populations have increased in some areas since 1950, there is little doubt that the changed think ing about moose management is more the result of the increase in knowledge than of any other factor. -

A Summary of Vulnerability of Habitats and Priority Species

Climate Change and Biodiversity in Maine: A Summary of Vulnerability of Habitats and Priority Species Andrew Whitman Phillip deMaynadier Barbara Vickery Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences ME Department of Inland Fisheries and The Nature Conservancy Andrew Cutko Wildlife Sally Stockwell ME Department of Agriculture, Conservation, Steve Walker Maine Audubon and Forestry Maine Coast Heritage Trust Robert Houston U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Introduction As we watch temperatures climb and experience extremes in weather, it is clear that climate change has become a tangible threat to Maine’s ecosystems. Long-term research has shown that Maine’s wildlife are already responding to climate change.1 We will likely lose some of Maine’s native wildlife and observe permanent changes to their habitats in the coming decades. By 2100, average temperatures may increase 3° to 13°F. In response, the predicted northward shift of species ranges has begun. Rising temperatures will allow pests such as Winter Moose Tick (Dermacentor albipictus) and Hemlock Wooly Adelgid (Adelges tsugae) to become more common, potentially harming native wildlife and their habitats. Drought may occur more frequently and impact all habitats, especially wetlands. Sea level will likely rise three to six feet and will flood coastal marshes and beaches. Recognizing these challenges, a team of Maine scientists assessed the vulnerability of wildlife and habitats to a changing climate and then identified general strategies to reduce their vulnerability.2 Other states have taken this first step as they aim to update their state wildlife action plans (SWAPs) by 2015. States originally created SWAPs to set conservation priorities and obtain additional federal funding for wildlife. -

High Conservation Value Forest Assessment Update – 2015 to 2020 1

HIGH CONSERVATION VALUE FOREST ASSESSMENT UPDATE 2015 – 2020 FSC ® Certification Period Port Hawkesbury Paper LP Liscomb River Large Landscape HCV Guysborough, Nova Scotia © Tree Top Images March 2015 Authors: Andrea Doucette, Port Hawkesbury Paper LP Chris Miller, Canadian Parks & Wilderness Society High Conservation Value Forest Assessment Update – 2015 to 2020 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A High Conservation Value Forest (HCV) assessment initially undertaken for the Port Hawkesbury Paper mill in 2010 (at that time called NewPage Port Hawkesbury) in accordance with Principle 9 of the Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC) Maritimes Standard was updated for the 2015-2020 FSC certification period to ensure original HCV’s are still relevant and new HCV’s are captured for the next 5-year period. This re-assessment resulted in the following HCV designations: HCV Category HCV Value CATEGORY 1 – BIODIVERSITY Question 1: Species at Risk Boreal Felt Lichen Occurrences Roseate Tern Habitat Bicknell’s Thrush Habitat Wood Turtle Habitat American Marten Habitat Mainland Moose Habitat Canada Lynx Habitat Rusty Blackbird Habitat New Jersey Rush Habitat Eastern White Cedar Frosted Glass-Whiskers Occurrences Vole Ears Lichen Occurrences Blue Felt Lichen Occurrences Black Ash Olive-sided Flycatcher Habitat Eastern Whip-poor-will Habitat Eastern Wood Peewee Habitat Canada Warbler Habitat Question 2: Endemic Species None identified Question 3: Seasonal Concentration of Species PHP Watersheds Cold-water streams for salmon and trout Question 4: Regionally Significant -

The Rewilding of New York's North Country: Beavers, Moose, Canines and the Adirondacks

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2008 The Rewilding of New York's North Country: Beavers, Moose, Canines and the Adirondacks Peter Aagaard The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Aagaard, Peter, "The Rewilding of New York's North Country: Beavers, Moose, Canines and the Adirondacks" (2008). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1064. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1064 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REWILDING OF NEW YORK‟S NORTH COUNTRY: BEAVERS, MOOSE, CANINES AND THE ADIRONDACKS By Peter Miles Aagaard Bachelor of Arts, State University of New York College at Geneseo, Geneseo, NY, 2005 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History The University of Montana Missoula, MT Spring 2008 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School Dr. Dan Flores, Chair Department of History Dr. Jeffrey Wiltse Department of History Dr. Paul R. Krausman Department of Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences ii Aagaard, Peter, M.A., May 2008 History The Rewilding of New York‟s North Country: Beavers, Moose, Canines, and the Adirondacks Chairperson: Dan Flores This project examines the restoration histories of beavers (Castor canadensis), moose (Alces alces americana), and wild canines (Canis spp.) within the Adirondack Highlands of northern New York. -

Species at Risk in Nova Scotia IDENTIFICATION & INFORMATION GUIDE

Species at Risk in Nova Scotia IDENTIFICATION & INFORMATION GUIDE Species at Risk in Nova Scotia IDENTIFICATION & INFORMATION GUIDE This guide was created for folks in Nova Scotia, like Harold and © Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute (MTRI), 2008. Diane, who want to learn more about the endangered species that Species at Risk in Nova Scotia - Identification & Information Guide live on the land around them: All rights reserved. This product is not to be sold or reproduced without permission from MTRI. Major funding for this initiative “Surveying for species at risk is an exciting adventure…because we was provided by Parks Canada's Priority Investment Fund for Species at Risk Recovery are looking for the most rare and fascinating creatures in Nova Scotia. When we find one we observe and appreciate it, but do our This guide is printed in Canada on FSC certified post consumer recycled paper. best not to disturb it…this way we can help a lot while having as little impact as possible" This field guide is also available online! - Harold & Diane Clapp Visit www.speciesatrisk.ca to view, download, or print an electronic version of this guide (online you can zoom in on the high resolution photos to see more detail). Since the status of species changes over time, as does our knowledge about them, we will provide web updates that reflect new information as it becomes available. DESIGN: TODD Graphic, www.toddgraphic.ns.ca N O N N I K C M R E F I N N E J i © Some Faces of the Species at Risk Community ii TOM HERMAN (ACADIA) BRENNAN CAVERHILL (PC) & -

Recovery Plan for Moose (Alces Alces Americana) in Mainland Nova Scotia

Recovery Plan for Moose in Mainland Nova Scotia March 2007 Nova Scotia Endangered Species Act Recovery Plan Series Recovery Plan for Moose (Alces alces americana ) in Mainland Nova Scotia March 2007 Recovery Plan for Moose in Mainland Nova Scotia March 2007 Recommended citation: Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources. 2007. Recovery Plan for Moose (Alces alces Americana) in Mainland Nova Scotia. Additional copies: Additional copies can be downloaded from the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources Species Recovery and Conservation webpage. (http://www.gov.ns.ca/natr/wildlife/biodiv/species_recovery.htm#moose) Cover illustration: From 1936 Nova Scotia Department of Lands & Forests Annual Report Recovery Plan for Moose in Mainland Nova Scotia March 2007 Recovery Plan for Moose (Alces alces americana) in Mainland Nova Scotia March 2007 Recovery of this species is considered technically or biologically feasible at this time. Recovery Plan for Moose in Mainland Nova Scotia March 2007 RESPONSIBLE JURISDICTIONS Government of Nova Scotia: Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Nova Scotia Mainland Moose Recovery Team provided much of the information which is the grounding and basis for the contents of this recovery plan. A list of members and their affiliations is found in Section 4. Special thanks to the Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute for their help in completing this recovery plan. In particular, thanks to Crystal Doggett, the coordinating author. PREFACE This recovery plan has been prepared by the responsible jurisdiction, the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources in cooperation with the Nova Scotia Mainland Moose Recovery Team. The recovery plan defines the recovery goal, objectives, strategies, and actions that are deemed necessary to protect, conserve, and recover mainland moose in Nova Scotia. -

Petition to List the U.S

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE U.S. POPULATION OF NORTHWESTERN MOOSE (ALCES ALCES ANDERSONI) UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT JULY 9, 2015 CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY HONOR THE EARTH NOTICE OF PETITION Sally Jewell, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Dan Ashe, Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Douglas Krofta, Chief Branch of Listing, Endangered Species Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] PETITIONERS The Center for Biological Diversity (Center) is a non-profit, public interest environmental organization dedicated to the protection of native species and their habitats through science, policy, and environmental law. The Center is supported by more than 900,000 members and activists throughout the United States. The Center and its members are concerned with the conservation of endangered species and the effective implementation of the Endangered Species Act. Honor the Earth is a Native-led organization, established by Winona LaDuke and Indigo Girls Amy Ray and Emily Saliers. Our mission is to create awareness and support for Native environmental issues and to develop needed financial and political resources for the survival of sustainable Native communities. Honor the Earth develops these resources by using music, the arts, the media, and Indigenous wisdom to ask people to recognize our joint dependency on the Earth and be a voice for those not heard. ii Submitted this 9th day of July, 2015 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), 16 U.S.C. -

Moose and Deer Population Trends in Northwestern Ontario: a Case History

MOOSE AND DEER POPULATION TRENDS IN NORTHWESTERN ONTARIO: A CASE HISTORY Bruce Ranta1 and Murray Lankester2 1311 Austin Lake Road, Kenora, Ontario, Canada P9N 4N2; retired; 2101-2001 Blue Jay Place, Courtenay, British Columbia, Canada V9N 4A8; retired. ABSTRACT: Many interrelated factors contribute to the rise and fall of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and moose (Alces alces) populations in the mixed boreal forests of eastern North America where these species often cohabit. A question not satisfactorily answered is why do moose populations periodically decline in a pronounced and prolonged way while deer populations continue to do well during times when habitat conditions appear good for both? Long-term historical data from the Kenora District of northwestern Ontario, Canada provided an opportunity to better understand temporal rela- tionships between trends in deer and moose numbers and landscape-level habitat disturbances, ensu- ing forest succession, climate, predators, and disease. Over the past 100 years, moose and deer have fluctuated through 2 high-low population cycles. Deer numbers were high and moose numbers were low in the 1940s and 50s following a spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) outbreak. By the early 1960s, deer trended downwards and remained low during an extended period with frequent deep-snow winters; as deer declined, moose recovery was evident. Moose increased through the 1980s and 1990s as did deer, apparently in response to considerable habitat disturbance, including another spruce budworm outbreak and easier winters. However, despite conditions that were favourable for both species, moose declined markedly beginning in the late 1990s, and by 2012 were at very low levels district-wide while deer numbers remained high. -

Moose Alces Alces Division of Fisheries & Wildlife State Status: None Federal Status: None

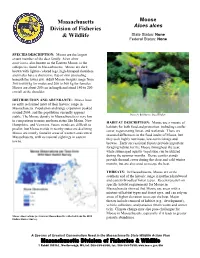

Massachusetts Moose Alces alces Division of Fisheries & Wildlife State Status: None Federal Status: None SPECIES DESCRIPTION: Moose are the largest extant member of the deer family. Alces alces americana, also known as the Eastern Moose, is the subspecies found in Massachusetts. Moose are dark brown with lighter-colored legs, high-humped shoulders, and males have a distinctive flap of skin protruding beneath the lower jaw. Adult Moose weights range from 360 to 600 kg for males and 200 to 360 kg for females. Moose are about 280 cm in length and stand 140 to 200 cm tall at the shoulder. DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE: Moose have recently reclaimed most of their historic range in Massachusetts. Population and range expansion peaked around 2004, and the population currently appears stable. The Moose density in Massachusetts is very low Photo by Bill Byrne, MassWildlife in comparison to more northern states like Maine, New HABITAT DESCRIPTION: Moose use a mosaic of Hampshire, and Vermont. Future trends are difficult to habitats for both food and protection, including conifer predict, but Moose trends in nearby states are declining. cover, regenerating forest, and wetlands. There are Moose are mostly found in areas of western and central seasonal differences in the food intake of Moose, but Massachusetts, with occasional sightings in eastern they seek highly nutritious, low-toxin foliage and towns. browse. Early successional forests provide important foraging habitat for the Moose throughout the year, while submerged aquatic vegetation can be utilized during the summer months. Dense conifer stands provide thermal cover during the clear and cold winter months, but are also used to escape the heat. -

Applying Emerging Genetic Methods to Wild Model Systems

Applying emerging genetic methods to wild model systems Ida-Maria Blåhed Faculty of Forest Sciences Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Environmental Studies Umeå Doctoral thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Umeå 2019 Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae 2019:40 Cover: “The challenges of quantifying nature” (illustration: Sven Norman) ISSN 1652-6880 ISBN (print version) 978-91-7760-398-6 ISBN (electronic version) 978-91-7760-399-3 © 2019 Ida-Maria Blåhed, Umeå Print: Arkitektkopia, Umeå 2019 Applying emerging genetic methods to wild model systems Abstract Genetic material is an invaluable source of information for assessments of wild populations. By using information derived from genetic markers, individuals can be identified and tracked over time, enabling studies of a wide range of behavioral, ecological, and evolutionary processes. At the population level, estimations of the distribution of genetic variation increase our knowledge about a wide range of population processes and can reveal barriers to gene flow, information that is important to integrate in both conservation- and management plans. This thesis presents new methods for individual- and population based assessments of deer (Cervidae), with a focus on moose (Alces alces). Molecular markers, SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms), were developed using two different approaches. First, cross- species amplification was explored between cattle and the five deer species occurring in Sweden; moose, roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), red deer (Cervus elaphus), fallow deer (Dama dama) and reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). Next, a reduced representation sequencing approach was chosen for de-novo SNP discovery in moose, with the main purpose of finding markers suitable for individual identification. As a result, a moose SNP panel including 86 autosomal, five sex-specific- and five species diagnostic SNPs was developed. -

Mass, Morphology, and Growth Rates of Moose in North Dakota

MASS, MORPHOLOGY, AND GROWTH RATES OF MOOSE IN NORTH DAKOTA William F. Jensen1, Jason R. Smith2, James J. Maskey Jr.3, James V. McKenzie (Deceased)1, and Roger E. Johnson (Retired)4 1North Dakota Game and Fish Department, 100 North Bismarck Expressway, Bismarck, North Dakota 58501 USA; 2North Dakota Game and Fish Department, 3320 East Lakeside Road, Jamestown, North Dakota 58401 USA; 3University of Mary, 7500 University Dr., Bismarck, North Dakota 58504 USA; 4North Dakota Game and Fish Department, 7928 45th Street NE, Devils Lake, North Dakota 58301 USA. ABSTRACT: This paper provides predictive formulas to estimate live weights of moose (Alces alces andersoni) from hunter-harvested animals and evaluate growth rates of moose in North Dakota, and reviews weight-related measurements among moose populations. From 1978–1990, morphometric data were collected on 224 hunter-killed moose harvested after the rut (10 November–12 December) in North Dakota. Body mass increased rapidly for both sexes from 0.5 years to 1.5 years-of-age. Whole weight and total body length reached an asymptote for both sexes by 5.5 years; mean whole weight appeared to decline among older individuals. Although field dressed weight was the best pre- dictor of whole weight (r2 = 0.93; n = 154), total body length provided reasonably good estimates of whole weight (r2 = 0.76; n = 153). Whole weight estimates based upon shoulder height (r2 = 0.33; n = 158) and hind-foot length (r2 = 0.46; n = 163) were less reliable. We also used morphometric vari- ables to predict field dressed weight, carcass weight, and visceral weight.