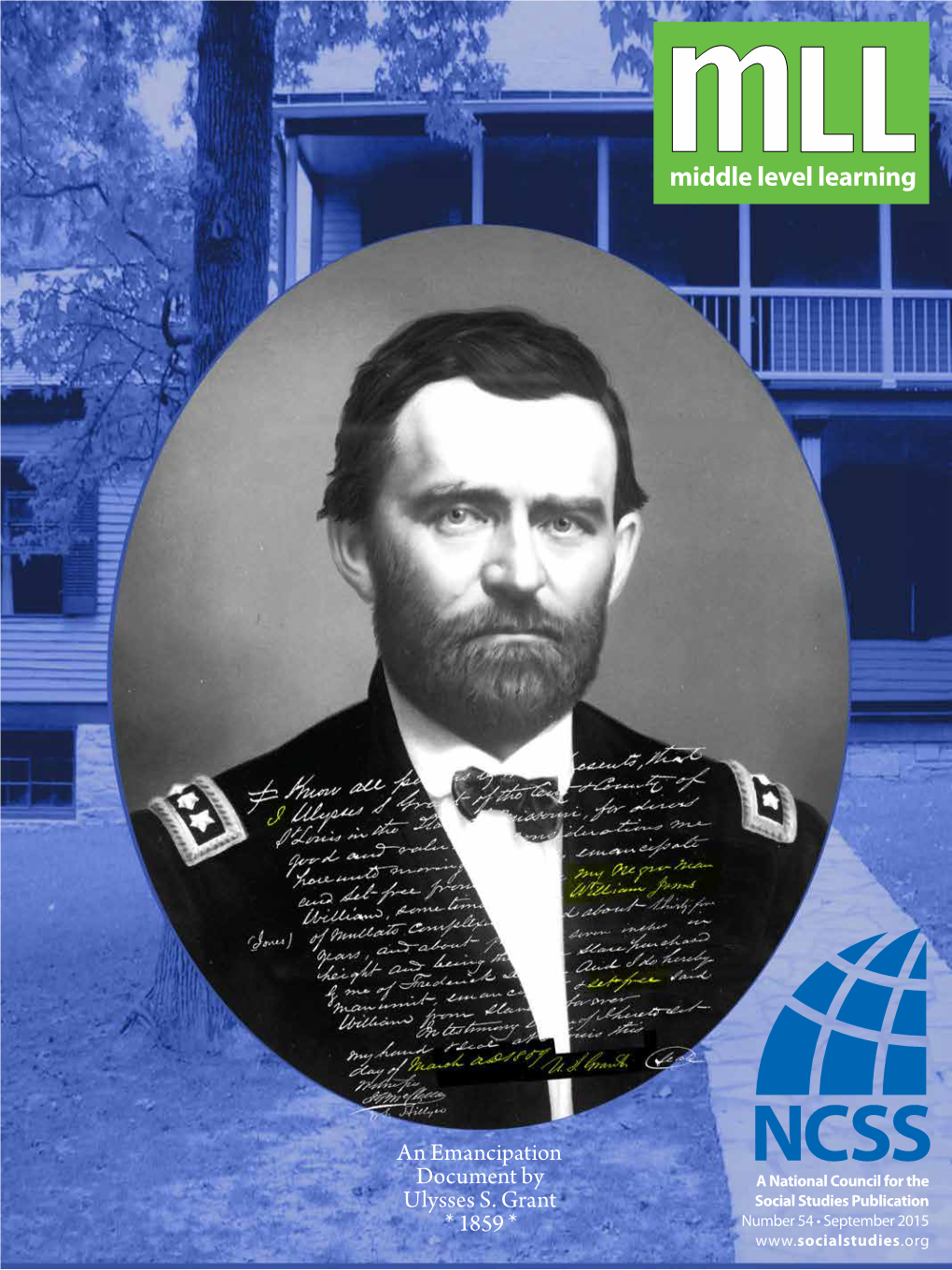

An Emancipation Document by Ulysses S. Grant * 1859 *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Ulysses 166 & 167 by Ronald C

American Ulysses 166 & 167 By Ronald C. White Reviewed by Robert Schmidt About the Author Ronald C. White is the author of American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant (2016). It won the William Henry Seward Award for Excellence in Civil War Biography awarded by the Civil War Forum of Metropolitan New York. General David H. Petraeus (Ret.) wrote, “Certain to be recognized as the classic work on Ulysses S. Grant.” White is also the author of three books on Abraham Lincoln. A. Lincoln: A Biography [2009], was a New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times bestseller, Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural and The Eloquent President: A Portrait of Lincoln Through His Words. About the Book So, who is buried in Grant’s tomb, anyway? That’s an old and insipid joke, of course, but considering what we think we know about the 18th President of the United States, a question worth asking might be hiding in there. With American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant, Ronald C. White endeavors over 800 pages (over 100 them being notes referencing primary and secondary sources) to shed light on one of our most influential yet enigmatic figures. This isn’t a revisionist biography; Grant already got that treatment in the early 20th century, when he transformed from a respected Civil War general and public servant into a craven opportunist and failed president, drunk and penniless at his death (just try imagining a destitute former POTUS in this era). White first redresses criticisms of his martial prowess—primarily that he exploited a huge numbers advantage by needlessly sacrificing troops in exchange for victory—with detailed accounts, maps, and illustrations of his conflicts, showing a battlefield acumen previously diminished through ad hominem barbs. -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

The Shadow of Napoleon Upon Lee at Gettysburg

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar The Shadow of Napoleon upon Lee at Gettysburg Charles Teague Every general commanding an army hopes to win the next battle. Some will dream that they might accomplish a decisive victory, and in this Robert E. Lee was no different. By the late spring of 1863 he already had notable successes in battlefield trials. But now, over two years into a devastating war, he was looking to destroy the military force that would again oppose him, thereby assuring an end to the war to the benefit of the Confederate States of America. In the late spring of 1863 he embarked upon an audacious plan that necessitated a huge vulnerability: uncovering the capital city of Richmond. His speculation, which proved prescient, was that the Union army that lay between the two capitals would be directed to pursue and block him as he advanced north Robert E. Lee, 1865 (LOC) of the Potomac River. He would thereby draw it out of entrenched defensive positions held along the Rappahannock River and into the open, stretched out by marching. He expected that force to risk a battle against his Army of Northern Virginia, one that could bring a Federal defeat such that the cities of Philadelphia, Baltimore, or Washington might succumb, morale in the North to continue the war would plummet, and the South could achieve its true independence. One of Lee’s major generals would later explain that Lee told him in the march to battle of his goal to destroy the Union army. -

Reviewing the Civil War and Reconstruction Center for Legislative Archives

Reviewing the Civil War and Reconstruction Center for Legislative Archives Address of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society NAID 306639 From 1830 on, women organized politically to reform American society. The leading moral cause was abolishing slavery. “Sisters and Friends: As immortal souls, created by God to know and love him with all our hearts, and our neighbor as ourselves, we owe immediate obedience to his commands respecting the sinful system of Slavery, beneath which 2,500,000 of our Fellow-Immortals, children of the same country, are crushed, soul and body, in the extremity of degradation and agony.” July 13, 1836 The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1832 as a female auxiliary to male abolition societies. The society created elaborate networks to print, distribute, and mail petitions against slavery. In conjunction with other female societies in major northern cities, they brought women to the forefront of politics. In 1836, an estimated 33,000 New England women signed petitions against the slave trade in the District of Columbia. The society declared this campaign an enormous success and vowed to leave, “no energy unemployed, no righteous means untried” in their ongoing fight to abolish slavery. www.archives.gov/legislative/resources Reviewing the Civil War and Reconstruction Center for Legislative Archives Judgment in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sanford NAID 301674 In 1857 the Supreme Court ruled that Americans of African ancestry had no constitutional rights. “The question is simply this: Can a Negro whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such, become entitled to all the rights and privileges and immunities guaranteed to the citizen?.. -

Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Dent Grant Papers Finding Aid

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction USGPL Finding Aids Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library 12-1-2020 Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Dent Grant papers Finding Aid Ulysses S. Grant Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/usgpl-findingaids Recommended Citation Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Dent Grant papers, Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library, Mississippi State University This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGPL Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Dent Grant papers USGPL.USGJDG This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on December 01, 2020. Mississippi State University Libraries P.O. Box 5408 Mississippi State 39762 [email protected] URL: http://library.msstate.edu/specialcollections Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Dent Grant papers USGPL.USGJDG Table of Contents Summary Information ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note: Ulysses S. Grant ................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Content Note ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative -

To Live and Die in Dixie: Robert E. Lee and Confederate Nationalism Jacob A

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects 2010 To Live and Die in Dixie: Robert E. Lee and Confederate Nationalism Jacob A. Glover Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Glover, Jacob A., "To Live and Die in Dixie: Robert E. Lee and Confederate Nationalism" (2010). Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects. Paper 267. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/267 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by Jacob A. Glover 2010 ABSTRACT Robert E. Lee is undeniably one of the most revered figures in American history, and yet despite the adoration awarded to the man over the years, surprisingly little scholarly research has dedicated itself to an inquiry into his nationalistic leanings during the four most important years of his life—the Civil War. In fact, Lee was a dedicated Confederate nationalist during his time in service to the Confederacy, and he remained so for the rest of his life, even after his surrender at Appomattox and the taking of an oath to regain his United States citizenship. Lee identified strongly with a Southern view of antebellum events, and his time in the Confederate army hardened him to the notion that the only practical reason for waging the Civil War was the establishment of an independent Southern nation. -

Juneteenth” Comes Ployer and Free Laborer

J UNETEENTH 92 C ELEBRATIONS UNETEENTH is the oldest celebration in the and the connection h eretofore existing be- nation to commemorate the end of slavery in tween them becomes that between em- J the United States. The word “Juneteenth” comes ployer and free laborer. from a colloquial pronunciation of “June 19th,” which With this announcement the last 250,000 slaves in is the date celebrations commemorate. the United States were effectively freed. Afterward In 1863 President Abraham Lincoln signed the many of the former slaves left Texas. As they moved to Emancipation Proclamation, offi - other states to fi nd family mem- cially freeing slaves. However, bers and start new lives, they car- word of the Proclamation did not ried news of the June 19th event reach many parts of the country with them. In subsequent decades right away, and instead the news former slaves and their descendants spread slowly from state to state. continued to commemorate June The slow spread of this important 19th and many even made pilgrim- news was i n part because the A mer- ages back to Galveston, Texas to ican Civil War had not yet ended. celebrate the event. However, in 1865 the Civil War Most of the celebrations ini- ended and Union Army soldiers tially took place in rural areas and began spreading the news of the included activities such as fi shing, war’s end and Lincoln’s Emanci- barbeques, and family reunions. pation Proclamation. Church grounds were also often On June 19, 1865, Major Gen- the sites for these celebrations. As eral Gordon Granger and U nion more and more African Americans Army soldiers arrived in Galves- improved their economic condi- ton, Texas. -

In This Issue: Monumental Memories Le Carillon National, Ah! Ça Ira and the Downfall of Paris, Part 1 Healy Flute Company Skip Healy Fife & Flute Maker

i AncientTimes Published by the Company of fifers & drummers, Inc. fall 2011 Issue 134 $5.00 In thIs Issue: MonuMental MeMorIes le CarIllon natIonal, ah! Ça Ira and the downfall of ParIs, Part 1 HeAly FluTe CompAny Skip Healy Fife & Flute maker Featuring hand-crafted instruments of the finest quality. Also specializing in repairs and restoration of modern and wooden Fifes and Flutes on the web: www.skiphealy.com phone/Fax: (401) 935-9365 email: [email protected] 5 Division Street Box 23 east Greenwich, RI 02818 Afffffordaordable Liability IInsurance Provided by Shoffff Darby Companiies Through membership in the Liivingving Histoory Associatiion $300 can purchaase a $3,000,000 aggregatte/$1,000,000 per occurrennce liability insurance that yyou can use to attend reenactments anywhere, hosted by any organization. Membership dues include these 3 other policies. • $5,010 0 Simple Injuries³Accidental Medical Expense up to $500,000 Aggggregate Limit • $1,010 0,000 organizational liability policy wwhhen hosting an event as LHA members • $5(0 0,000 personal liability policy wwhhen in an offfffiicial capacity hosting an event th June 22³24 The 26 Annual International Time Line Event, the ffiirst walk througghh historryy of its kind establishedd in 1987 on the original site. July 27³29 Ancient Arts Muster hosting everything ffrrom Fife & DDrum Corps, Bag Pipe Bands, craffttspeople, ffoood vendors, a time line of re-enactors, antique vehicles, Native Ameericans, museum exhibits and more. Part of thh the activities during the Annual Blueberry Festival July 27³AAuugust 5 . 9LVLWWKH /+$·VZHEVLWHDW wwwwwww.lliivviinnggghhiissttooryassn.oorg to sign up ffoor our ffrree e-newsletter, event invitations, events schedules, applications and inffoormation on all insurance policies. -

History News Speaking Confidently in Her Native Language Also New to the National Register Quieted the Crowd

N E B R A S K A history Volumenews 63 / Number 2 / April/May/June 2010 I Hear America Singing: The Neligh Mills Jamboree ome to Neligh Mill State Historic Site on July 4th to hear Nebraska sing at Cthe Neligh Mills Jamboree. From 5:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. the Elkhorn Valley will ring with the music of four Nebraska traditions. The title of the event, I Hear America Singing, comes from the Walt Whitman poem that celebrates America’s many voices. At Neligh you will hear those American sounds. The Kenaston Family, folks with deep roots in the Sandhills ranch country, is a country band known for their instrumental and vocal virtuosity. Mariachi Zapata will add the excitement and energy of Mexican music. You will hear the Plains once again resonate to the voices of American Indians with Young Generation, members of the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska who perform at powwows and other gatherings. And the Ne- braska Chapter of the Gospel Workshop of Portrait of Louis Armstrong painted by John Falter America, winner of the 2010 Governor’s Heri- tage Arts Award, will have everyone moving Falter’s Armstrong, to the soulful voice of gospel music. Chappell’s Teagarden This open air concert is free and family Why does the NSHS have a portrait of friendly. Bring your lawn chairs or blankets Louis Armstrong? The painting is part of our for a good celebration of our nation’s collection of work by Nebraska-born illustrator birthday. The concert is part of Neligh’s John Falter (see p. -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: -

8Th US History Civil War and Reconstruction Units

8th US History Civil War and Reconstruction Units 1. Complete the first 4 weeks of work in order. The first week covers the Civil War. If you can answer the questions without completing all of the reading, you may do so, as you should have learned the majority of this content in class. Within the unit there are two video lessons, one about Harriet Tubman and another about the 54th Massachusetts. If you have access to your phone or the internet, watch the videos as they are assigned to complete the questions. 2. Weeks 2, 3, and 4 over lessons we have yet to cover in class, including about the period of time after the Civil War, called Reconstruction. You should use the textbook reading to complete the questions and assignments in this section. 3. Week 5 focuses on the STAAR practice unit. Please access the quizlet link on page 76, review the “US History at a glance” pages, and answer the practice problems using the “at a glance” information. 4. For online games, activities and extra practice check out: https://www.icivics.org/games 5. Khan Academy provides a free, online module for 8th Grade US History, including topic overviews and practice. Focus on The Civil War era (1844-1877) https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history WEEK 1 The Civil War 21.1 Introduction he cannon shells bursting over Fort Sumter ended months of confu sion. The nation was at war. The time had come to choose sides. TFor most whites in the South, the choice was clear. -

US Grant: Warrior (2011)

Page 1 U.S. Grant: Warrior (2011) Program Transcript Narrator: "My family is American and has been for generations in all its branches, direct and collateral," he would write. Ulysses S. Grant grew up in the Ohio River Valley. His father, Jesse Root Grant, had arrived in Georgetown, Ohio in 1823, when Grant was one year old. He was the descendant of pioneers who had settled the western frontier. "I attended the village schools," Grant said of his childhood. "I was not studious in habit, but never missed a quarter." When Ulysses was 16, he learned that his father had gotten him an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. John Y. Simon, Historian: Jesse Grant was the kind of man who would follow a dollar to hell. And when he learned about the possibility of sending his son to West Point at government expense, he jumped at the opportunity. It was only when the appointment was a sure thing that he finally told Ulysses that he's going to West Point. Young Grant said, "I won't go." And Jesse said, "You will." Narrator: When Ulysses Grant arrived at West Point, he stood five feet one inch, and weighed just 117 pounds. "I had a very exalted idea of the requirements necessary to get through," he wrote. "I did not believe I possessed them, and could not bear the idea of failing." Grant was out of place in the West Point cadet's world of military drills, crossed belts, and gleaming brass. Max Byrd, Novelist: He didn't have the military bearing.