Point and Figure Charting 55

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point and Figure Charts

Point and Figure Charts Point-and-figure (P&F) chart is a special type of graphical analysis, which lays stress to prediction of medium-term and long-term trends. Conclusion Let’s single out advantages and disadvantages of Point and Figure charts. Point and Figure Advantages 1. P&F charts send only clear buy or sell signals without any dual nature. 2. P&F charts take into account only “important” price changes and filter out market noise. This being said, the “importance” of changes is set by a trader. 3. P&F charts are not affected by time effect, which sometimes introduces additional element of uncertainty on general charts. 4. P&F charts allow to identify support and resistance levels, and also trend lines. 5. P&F charts are very intelligible. Point and Figure Disadvantages 1. P&F charts send clear signals only for medium-term and long-term periods and are almost not intended for short-term trade. Building Point and Figure Charts The majority of the most popular charts, used for technical analysis, are built in accordance with opening price, closing price, maximum or minimum for a definite period. Only closing price for a period is used for building Point and Figure charts. Point and Figure charts consist of X and O columns, which reflect the filtered price changes. Increase in prices is shown by “X” boxes, and drop in prices is shown by “O” boxes. New boxes are created only in case of price change by the size of a box or more in one of directions. -

Point and Figure Relative Strength Signals

February 2016 Point and Figure Relative Strength Signals JOHN LEWIS / CMT, Dorsey, Wright & Associates Relative Strength, also known as momentum, has been proven to be one of the premier investment factors in use today. Numerous studies by both academics and investment ABOUT US professionals have demonstrated that winning securities continue to outperform. This phenomenon has been found Dorsey, Wright & Associates, a Nasdaq Company, is a in equity markets all over the globe as well as commodity registered investment advisory firm based in Richmond, markets and in asset allocation strategies. Momentum works Virginia. Since 1987, Dorsey Wright has been a leading well within and across markets. advisor to financial professionals on Wall Street and investment managers worldwide. Relative Strength strategies focus on purchasing securities that have already demonstrated the ability to outperform Dorsey Wright offers comprehensive investment research a broad market benchmark or the other securities in the and analysis through their Global Technical Research Platform investment universe. As a result, a momentum strategy and provides research, modeling and indexes that apply requires investors to purchase securities that have already Dorsey Wright’s expertise in Relative Strength to various appreciated quite a bit in price. financial products including exchange-traded funds, mutual funds, UITs, structured products, and separately managed There are many different ways to calculate and quantify accounts. Dorsey Wright’s expertise is technical analysis. The momentum. This is similar to a value strategy. There are Company uses Point and Figure Charting, Relative Strength many different metrics that can be used to determine a Analysis, and numerous other tools to analyze market data security’s value. -

Lesson 12 Technical Analysis

Lesson 12 Technical Analysis Instructor: Rick Phillips 702-575-6666 [email protected] Course Description and Learning Objectives Course Description Learn what technical analysis entails and the various ways to analyze the markets using this type of analysis Lessons and Learning Objectives ▪ Define technical analysis ▪ Explore the history of technical analysis ▪ Examine the accuracy of technical analysis ▪ Compare technical analysis to fundamental analysis ▪ Outline different types of technical studies ▪ Study tools and systems which provide technical analysis 2 What is Technical Analysis Short Description: Using the past to predict the future Long Description: A way to analyze securities price patterns, movements, and trends to extrapolate the ranges of potential future prices 3 History of Technical Analysis The principles of technical analysis are derived from hundreds of years of financial market data. Some aspects of technical analysis began to appear in Amsterdam-based merchant Joseph de la Vega's accounts of the Dutch financial markets in the 17th century. In Asia, technical analysis is said to be a method developed by Homma Munehisa during the early 18th century which evolved into the use of candlestick techniques, and is today a technical analysis charting tool. In the 1920s and 1930s, Richard W. Schabacker published several books which continued the work of Charles Dow and William Peter Hamilton in their books Stock Market Theory and Practice and Technical Market Analysis. In 1948, Robert D. Edwards and John Magee published Technical Analysis of Stock Trends which is widely considered to be one of the seminal works of the discipline. It is exclusively concerned with trend analysis and chart patterns and remains in use to the present. -

Bullish Percent Index – See How to Time Bull and Bear Markets

Bullish percent index – See How to Time Bull and Bear Markets We can all agree that the bullish percent index (BPI) is a market breadth indicator that we can use to gauge market health. But is the indicator something you should use when trading? More importantly, if you do use the indicator when trading, when and how should you place your orders. Wellin this post, we will dissect how the BPI can be used to navigate the waters and some specific techniques you can use to increase your odds. Why Should You Care About the BPI? The BPI indicator is calculated by taking the total number of issues in an index or industry that are generating point and figure buy signals and dividing it by the total number of stocks in that group. The basic rule for using the bullish percent index is when the BPI is above 70%, the market is overbought, and conversely, when the indicator is below 30%, the market is oversold. The most popular BPI is the NYSE Bullish Percent Index, which is the tool of choice for famed point and figure analyst, Thomas Dorsey. The bullish percent index is generally plotted on with a two-point box size. Later in this article, we will cover how to confirm bull and bear markets. Bullish percent index or BPI for short might seem as just another fancy name for a market breadth indicator. Between the BPI and many other similar indicators, one might wonder the need to use this indicator. Well, the BPI is an indicator for the stock markets which is quite unique. -

Technical Analysis Explained by Martin J

Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter I ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 What is Technical Analysis?....................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Definition of Technical Analysis ...................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Philosophy of Technical Analysis .................................................................................................... 4 1.3. Technical Analysis vs. Fundamental Analysis ................................................................................. 5 1.4. Technician or Chartist? Is There Any Difference? .......................................................................... 6 1.5. Different Theories on Technical Analysis ....................................................................................... 6 Chapter II ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 Trend In Terms of Technical Analysis ....................................................................................................... -

Core Point and Figure Chart Patterns

Core Point and Figure Chart Patterns Charles Dow invented the basics of “supply and demand” charting, point and figure, in the late 1800’s. It’s been used ever since. Charts effectively show “historical perspectives” best, and chartists are always watching to see what leading indicators will predict “what’s next.” Using point and figure as a methodology for seeing prior supply and demand also helps the chartist eliminate “noise.” “Noise” is what we call “too much information, and too many facts” that are put in front of the average investor. Many option traders wrongly believe that the more charting and detailed information (bells and whistles) they have to trade with, the better. This is dangerously wrong. Remember, charts provide lagging information. Point and Figure charts provide leading information, around supply and demand. “Noise” allows for interpretation and it’s typically here that option traders begin to think “they see” what will happen. Using Point and Figure helps the trader see “the history of the supply and demand” and work with support and resistance lines to know what will happen next. Point and Figure charting is really the best “leading indicator” we have out there, as it shows what happened before around support and resistance lines. This is where the “history of the chart” can predict future movement. As you become well versed in Point and Figure, you’ll learn the core structure that is used is a 3:1 ratio. We explore .5 and 2 pt scales and various “views” of the index. We recommend also to learn to chart point and figure by hand. -

Relative Strength and Have a Good Probability of Outperforming the Market

Dorsey Wright Reference Manual About the Company Dorsey, Wright & Associates (DWA) is an independent and privately owned registered investment advisory firm founded in 1987 whose business includes two areas -- investment research services for numerous broker-dealers and large institutions around the world, and professional management of equity portfolios for investors. The two principals of the firm, Thomas J. Dorsey and Watson H. Wright, have extensive experience in the equity markets, particularly in the field of risk management. Combined, Mr. Dorsey and Mr. Wright have over 45 years of experience in the equity and options markets. Tom Dorsey is the author of Point & Figure Charting: The Essential Applications for Forecasting and Tracking Market Prices, Thriving As A Stockbroker in the 21st Century and Tom Dorsey’s Trading Tips: A Play Book for Stock Market Success. As well, the second edition of Point & Figure Charting was released in the summer of 2001. Point & Figure Charting has been translated into German, Polish, two dialects of Chinese, Hindu, and Japan has just purchased the rights for translation. Tom Dorsey and Tammy DeRosier, Vice President, also appear regularly on CNBC’s “Taking Stock” Program and Bloomberg TV. Dorsey, Wright analysts are featured on several national radio shows weekly too. Dorsey, Wright research is conducted along technical lines, adhering to the relationship between supply and demand. We believe this simple economic theory is manifested as a constant battle between these two forces for control of the equity vehicle. It is this objective, logical approach which helps reduce uncertainty in the market. The mainstay of the research at DWA is the Point & Figure methodology which was first popularized by Charles Dow in the late 1800’s. -

161962112.Pdf

VSB – TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF OSTRAVA FACULTY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE Verification of Technical Analysis Rules using Matlab Ověření pravidel technické analýzy s využitím SW Matlab Student: Bc. Anlan Wang Supervisor of the diploma thesis: doc. Ing. Aleš Kresta, Ph.D. Ostrava 2018 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 5 2. Description of Matlab ................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Introduction of Matlab ...................................................................................... 6 2.2 Basic Operations in Matlab ............................................................................... 7 2.2.1 Command Window ................................................................................. 7 2.2.2 Workspace ............................................................................................... 9 2.2.3 Command History ................................................................................... 9 2.2.4 Current Folder ....................................................................................... 10 2.3 Matlab Programming Structure....................................................................... 10 2.3.1 Sequential Structure .............................................................................. 10 2.3.2 Loop Structure ...................................................................................... 11 2.3.3 Branch -

Technical Analysis: Connecting the Dots Or a Legitimate Investment Tool?

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-10-1996 Technical Analysis: Connecting the Dots or a Legitimate Investment Tool? Daniel P. Sutter Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Sutter, Daniel P., "Technical Analysis: Connecting the Dots or a Legitimate Investment Tool?" (1996). Honors Theses. 2088. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2088 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CARL AND WINIFRED LEE HONORS COLLEGE CERTIFICATE OF ORAL EXAMINATION Daniel P. Sutter, having been admitted to the Carl and Winifred Lee Honors College in 1992, successfully presented the Lee Honors College Thesis on April 10, 1996. The title of the paper is: "Technical Analysis: Connecting the Dots or a Legitimate Investment Tool" Dr. Adrian Edwards Finance and Commerical Law Dr. David Burnie Finance and Commercial Law Dr. James D'Mello Finance and Commerical Law Technical Analysis: Connecting the Dots or a Legitimate Investment Tool? by Daniel P. Sutter Haworth College ofBusiness Lee Honors College 1996 Honors Thesis Special Thanks to: Dr. Ed Edwards Thesis Committee Chair Thesis Committee: -

Glossary of Technical Analysis Terms

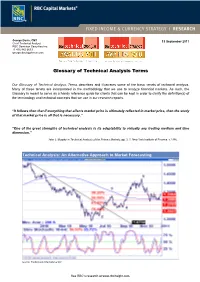

George Davis, CMT 13 September 2011 Chief Technical Analyst RBC Dominion Securities Inc. +1 416 842 6633 [email protected] Glossary of Technical Analysis Terms Our Glossary of Technical Analysis Terms describes and illustrates some of the basic tenets of technical analysis. Many of these tenets are incorporated in the methodology that we use to analyze financial markets. As such, the Glossary is meant to serve as a handy reference guide for clients that can be kept in order to clarify the definition(s) of the terminology and technical concepts that we use in our research reports. “It follows then that if everything that affects market price is ultimately reflected in market price, then the study of that market price is all that is necessary.” “One of the great strengths of technical analysis is its adaptability to virtually any trading medium and time dimension.” John J. Murphy in Technical Analysis of the Futures Markets, pp. 3, 7, New York Institute of Finance, c.1986. Technical Analysis: An Alternative Approach to Market Forecasting Source: Tradermade International Ltd. See RBC’s research at www.rbcinsight.com. 13 September 2011 Glossary of Technical Analysis Terms Table of Contents Glossary of Technical Analysis Terms............................................. 1 Table of Contents ............................................................................... 2 Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Types of Charts ................................................................................. -

Upped & Converted by Cracksniper for Gigapedia.Org

www.rasabourse.com Upped & Converted by cracksniper for gigapedia.org 2 www.rasabourse.com CONTENTS About the Contributors .............................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................... 7 Drummond Geometry: Picking Yearly Highs and Lows in Interbank Forex Trading ......................................................................................................................... 11 Trend Spotting With TD Combo ............................................................................ 25 Charting With Candles and Clouds .................................................................... 35 Reading Candlestick Charts ................................................................................. 47 Price and Time ........................................................................................................... 72 Unlocking Gann ........................................................................................................ 94 Options-Based Technical Indicators for Stock Trading ............................... 104 Point and Figure Analysis: Modern Developments in an Old Technique ..................................................................................................................................... 118 Deconstructing the Market: The Application of Market Profile to Global Spreads ..................................................................................................................... -

Nifty P&F Analysis

Nifty P&F analysis Medium term P&F chart of Nifty has turned to sideways and indicate broader price consolidation Nifty 10 x 3 (Short-term) Point & Figure chart has witnessed bearish breakout below 8170 as shown in the chart. With triangle breakout, price has formed Mini-top at 8260. Current formation is bearish and below 45 degree trend line. Bearish counts triggered after forming Mini-top are closed (achieved) as shown in the chart. Trend is down, but 1% x 3 breadth indicator of Nifty 50 universe has gone below 20% that indicates exhaustion which is typically followed by price or time correction. Hence Risk reward is not in favour of fresh positional bearish trades unless breadth moves in to neutral zone. Exactly opposite was the scenario when we published our last newsletter, fresh bullish trades were not looking affordable then. We comment on daily basis on trading strategy that one should follow based on P&F trend and breadth analysis at www.definedge.com Bank Nifty P&F analysis Bank Nifty 0.25% x 3 P&F chart has triggered multi-column breakdown formation as shown in the chart Chart pattern has turned bearish and price is trading below 45 degree trend line Bearish counts are open in the chart that can be referred till price maintains the bearish Mini-top price level which is placed at 18670. Relative strength P&F chart of Bank Nifty to Nifty has formed bearish follow-through formation that shows that sector has been one of the underperformers to Nifty index Look for next formation when breadth is supportive Multi-column breakdown pattern and ratio studies applied are explained elsewhere in this newsletter Sector Relative Strength analysis P&F Relative strength charts plot ratio line of two instruments as Point & Figure.