Dependent Independence the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

08-31-1907 Ramon Magsaysay.Indd

This Day in History… August 31, 1907 Birth of Ramon Magsaysay Ramon del Fierro Magsaysay Sr. was born on August 31, 1907, in Iba, Zambales, Philippine Islands. The Philippines’ seventh president, his administration was known for being free of corruption. He was later called the “Champion of the Masses” and “Defender of Democracy.” Magsaysay grew up in the Zambales province of the Philippines. He attended the University of the Philippines, initially enrolling in the pre-medical program and later studying engineering. He worked as a chauffeur to pay his way and then transferred to the Institute of Commerce at José Rizal College. Magsaysay worked as an automobile mechanic until World War II began. He then joined the Philippine Army’s 31st Infantry This was the first stamp in the Champions of Liberty Series Division motor pool. Magsaysay escaped and was issued just five months Japanese capture after the fall of Bataan and after Magsaysay’s death. organized the Western Luzon Guerrilla Forces. Commissioned as a captain, he eventually commanded a force of 10,000 Corregidor was captured after the soldiers that dislodged Japanese forces from the Zambales coast before the fall of Bataan. arrival of American troops in January 1944. After the war, Magsaysay’s former guerrillas encouraged him to run for office and he was elected to the Philippine House of Representatives in 1946. Two years later, he went to Washington, DC, as chairman of the Committee on Guerrilla Affairs to help get a bill passed that would give benefits to Philippine veterans. Magsaysay was elected to a second term in 1949 and served as chairman of the House National Defense Committee during both terms. -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP. -

FOURTEENTH CONGRESS of the . T ~~~.~~~~~~~

FOURTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE 1 11. REPUBLIC OF THE PEULIPPINES ) i pC'[ -9 I> i . t ..~4 First Regular Session 1 SENATE ~~~.~~~~~~~UY :.-. INTRODUCED BY SENATOR ANTONIO F. TRILLANES AND SENATOR MAR ROUS EXPLANATORY NOTE It has been observed that a number of major streets in Metro Manila have been renamed in honor of past presidents of the country, namely, Manuel L. Quezon, Jose P. Laurel, Manuel A. Roxas, Elpidio Quirino and Ramon Magsaysay. Be that as it may, there is no major street in this premier metropolis that has been named or a monument of substance built in honor of General Emilio Aguinaldo, the President of the First PhiIippine Republic. President Aguinaldo, whose presidency was inaugurated on June 12, 1898 in Kawit, Cavite, remains to be unappreciated and underrepresented especially in matters that can exalt him for his unprecedented leadership. Considering that we are celebrating the 1 anniversary of First Philippine Republic next year (2008), it is a propitious time to give honor to the distinguished Filipino who was one of the leaders who signed the Pact of Biak-na-Bat0 and was the president of the Supreme Council of the Biak-na-Bat0 Republican Government, and who also led the resistance against the American imperialist forces. This bill, therefore, seeks to give due recognition to the valor and statesmanship of General Aguinaldo by renaming Circumferential Road 5 (from SLEX to Commonwealth Avenue), located in Metro Manila, as Emilio Aguinaldo Avenue. The role of Aguinaldo, the military leader of the Republic, is entitled to a "long-delayed place of honor" in the national pantheon of heroes. -

Filipino Guerilla Resistance to Japanese Invasion in World War II Colin Minor Southern Illinois University Carbondale

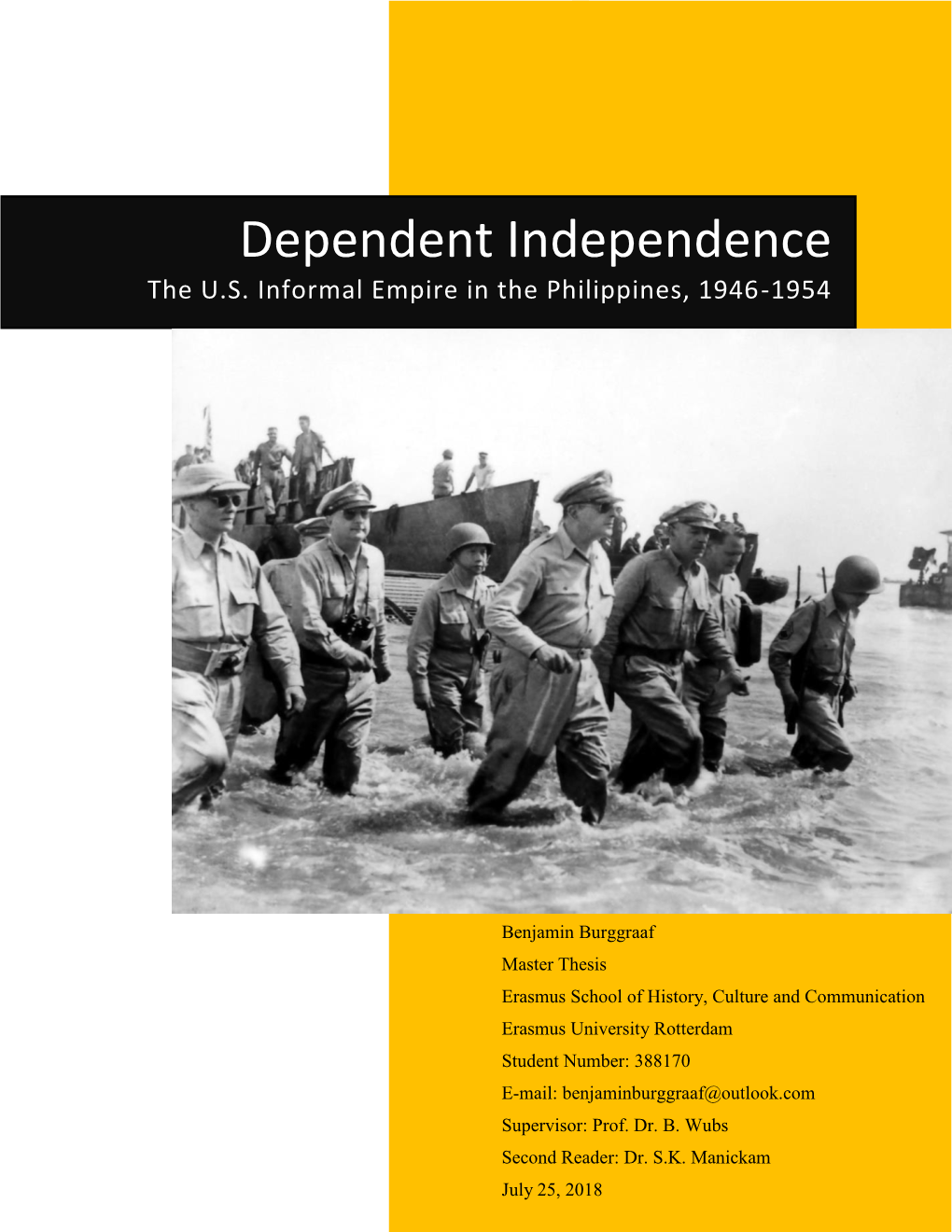

Legacy Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 5 Filipino Guerilla Resistance to Japanese Invasion in World War II Colin Minor Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/legacy Recommended Citation Minor, Colin () "Filipino Guerilla Resistance to Japanese Invasion in World War II," Legacy: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/legacy/vol15/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Legacy by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Colin Minor Filipino Guerilla Resistance to Japanese Invasion in World War II At approximately 8:00 pm on March 11, 1942, General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United States Army Forces in the Far East, along with his family, advisors, and senior officers, left the Philippine island of Corregidor on four Unites States Navy PT (Patrol Torpedo) boats bound for Australia. While MacArthur would have preferred to have remained with his troops in the Philippines, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Army Chief of Staff George Marshall foresaw the inevitable fall of Bataan and the Filipino capital of Manila and ordered him to evacuate. MacArthur explained upon his arrival in Terowie, Australia in his now famous speech, The President of the United States ordered me to break through the Japanese lines and proceed from Corregidor to Australia for the purpose, as I understand it, of organizing the American offensive against Japan, a primary objective of which is the relief of the Philippines. -

The Philippine Council for Sustainable Development: Like Cooking Rice Cakes

THE PHILIPPINE COUNCIL FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: LIKE COOKING RICE CAKES BY ESTER C. ISBERTO September 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Establishment and Organization............................................................................2 II. Emergence of the PCSD in the Development of a National Agenda 21 ................2 III. Accomplishments and Activities .........................................................................4 IV. General Assessment .............................................................................................6 I. Establishment and Organization It has long been a source of pride for the Philippine government that Manila was among the first to take action on its commitments to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED). On Sept. 15, 1992, barely three months after the Rio Summit, then President Fidel Ramos created the Philippine Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD). The Council was to be the key mechanism for fulfilling the Philippines’ pledge to implement Global Agenda 21, UNCED’s program of action for promoting sustainable development. When it was established, the PCSD was unique in that its counterparts in other countries were government-dominated bodies with little participation by non-government or people’s organizations (NGOs or POs). By contrast, the Philippine model gave strong representation to NGO/PO members (over a third of the council’s 34 members). Though government representatives can easily outvote their non-governmental counterparts, the PCSD’s practice of making decisions on the basis of consensus effectively gives the NGO and PO representatives influence on the mainstream of government policy-making. In retrospect, this factor should have come as little surprise, given the Philippines’ recent history. NGOs and POs emerged from the long years of the Marcos regime as influential pressure groups pursuing various causes in the country’s restored democracy. -

Wave of Pro-Democracy Movements Around the World;

__c_-- FOURTEENTI-1 CONGRESS OF THE ) REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES ) Third Regular Session 1 SENATE INTRODUCED BY SENATOR VILLAR RESOLUTION EXPlXESSlNG THE SENSE OF THE SENATE AS IT JOINS THE NATION IN MOURNING THE LOSS OF A TRUE FlLIPlNO WHO STOOD FOR DEMOCRACY, TRUTI-I AND PEACE, FORMER PRESIDENT CORAZON COJUANGCB AQUINO Whereas, Maria Corazon Cojuangco was born on January 25, 1933, in Paniqui, Tarlac; Whereas, she was the widow of rormer Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr., an opposition leader and long-time critic of the Marcos administration, who was assassinated on the tarmac of the Manila International Airport upon returning from exile on August 21, 1983; Wlrereas, her husband's assassination sparked a nationwide opposition movement that thrust her into the role of national leader; Whereas, Mrs. Aquino, with the backing of the military, rallied the Filipinos in the 1986 people power revolt that toppled the 20-year regime of strongman Ferdinand Marcos aid catapulted her to the presidency on February 25, 1986; Wherens, she became an international icon of democracy after her victory triggered a wave of pro-democracy movements around the world; Whereas, Mrs. Aquino was named Woman of the Year by Time Magazine in 1986: Whereas, in 1998, she received the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award for International Understanding; Whereas, the six-year administration of President Aquino, which ended on June 30, 1992, saw the enactment of a new Philippine Constitution and several significant legal reforms, including a new agrarian reform law; Wltereas, shc died of cardiopulmonary arrest after complications of colon cancer at thc age or76 on August l,2009,3:18am at the Makati Medical Center; Now thererore be it RESOLVED, as it is hereby resolved, expressing the sense of the Senate as it joins the nation in mourning the loss of a true Filipino who stood for democracy, truth and peace, former President Corazon Cojuangco Aquino. -

Today in the History of Cebu

Today in the History of Cebu Today in the History of Cebu is a record of events that happened in Cebu A research done by Dr. Resil Mojares the founding director of the Cebuano Studies Center JANUARY 1 1571 Miguel Lopez de Legazpi establishing in Cebu the first Spanish City in the Philippines. He appoints the officials of the city and names it Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre de Jesus. 1835 Establishment of the parish of Catmon, Cebu with Recollect Bernardo Ybañez as its first parish priest. 1894 Birth in Cebu of Manuel C. Briones, publisher, judge, Congressman, and Philippine Senator 1902 By virtue of Public Act No. 322, civil government is re established in Cebu by the American authorities. Apperance of the first issue of Ang Camatuoran, an early Cebu newspaper published by the Catholic Church. 1956 Sergio Osmeña, Jr., assumes the Cebu City mayorship, succeeding Pedro B. Clavano. He remains in this post until Sept.12,1957 1960 Carlos J. Cuizon becomes Acting Mayor of Cebu, succeeding Ramon Duterte. Cuizon remains mayor until Sept.18, 1963 . JANUARY 2 1917 Madridejos is separated from the town of Bantayan and becomes a separate municipality. Vicente Bacolod is its first municipal president. 1968 Eulogio E. Borres assumes the Cebu City mayorship, succeeding Carlos J. Cuizon. JANUARY 3 1942 The “Japanese Military Administration” is established in the Philippines for the purpose of supervising the political, economic, and cultural affairs of the country. The Visayas (with Cebu) was constituted as a separate district under the JMA. JANUARY 4 1641 Volcanoes in Visayas and Mindanao erupt simultaneously causing much damage in the region. -

Legitimacy and the Political Elite in the Philippines

Legitimacy and the Political Elite in the Philippines REMIGIO E. AGPALO Legitimacy is vitally important and indispensable to the political elite because without it their government will be vulnerable to political turmoil or revolution; conducive to coup d'etat or rebellion, or at least promotive of a feeling of alienation on the part of the people. Since the political elite will not want to have a coup d'etat against themselves, fan the flames of political turmoil, rebellion, or revolution in their domain, or promote the aiienation of the people -any one of these spells disaster to thems~::lves or at least instability of their rule-·- the political elite will strive to develop the legitimacy of their government. The political elite of various political systems, however, do not have the same problem of legitimacy. 1 The problem of legitimacy may be caused by the lack of charisma of the political elite. In other cases, they are new men in traditional societies who have replaced traditional leaders. In a few states, where the laws are highly institutionalized, the political elite have violated the legal and rational rules of the regime. In several Third World new nations, the political elite came to power by means of coup d'etat or revolution. Some went beyond their normal terms of office after a proclamation of martial law, a state of siege, or a state of national emergency, thus disrupting or changing the normal activities of political life. This paper attempts to shed light on the problem of legitimacy of the political elite in the Philippines. -

US-Philippine Relations, 1946-1972

Demanding Dictatorship? US-Philippine Relations, 1946-1972. A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2016 Ben Walker School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract. 3 Declaration and Copyright Statement. 4 Acknowledgements. 5 Introduction. From Colony to Cold War Ally: The Philippines and American Foreign Policy, 1898-1972. 6 1. ‘What to do with the Philippines?’ Economic Forces and Political Strategy in the United States’ Colonial Foreign Policy. 28 2. A New World Cold War Order: ‘Philippine Independence’ and the Origins of a Neo-Colonial Partnership. 56 3. To Fill the Void: US-Philippine Relations after Magsaysay, 1957-1963. 87 4. The Philippines after Magsaysay: Domestic realities and Cold War Perceptions, 1957-1965. 111 5. The Fall of Democracy: the First Term of Ferdinand Marcos, the Cold War, and Anti-Americanism in the Philippines, 1966-1972. 139 Conclusion. ‘To sustain and defend our government’: the Declaration of Martial Law, and the Dissolution of the Third Republic of the Philippines. 168 Bibliography. 184 Word Count: 80, 938. 3 Abstract In 1898 the Philippines became a colony of the United States, the result of American economic expansion throughout the nineteenth century. Having been granted independence in 1946, the nominally sovereign Republic of the Philippines remained inextricably linked to the US through restrictive legislation, military bases, and decades of political and socio-economic patronage. In America’s closest developing world ally, and showcase of democratic values, Filipino President Ferdinand Marcos installed a brutal dictatorship in 1972, dramatically marking the end of democracy there. -

A Legacy Public Health

THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public Health SECOND EDITION 2 Introduction THE Pre-SPANISH ERA ( UNTIL 1565 ) 0 3 This book is dedicated to the women and men of the DOH, whose commitment to the health and well-being of the nation is without parallel. 3 3 THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public Health SECOND EDITION Copyright 2014 Department of Health All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or me- chanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and information system, without the prior written permis- sion of the copyright owner. 2nd Edition Published in the Philippines in 2014 by Cover & Pages Publishing Inc., for the Department of Health, San Lazaro Compound, Tayuman, Manila. ISBN-978-971-784-003-1 Printed in the Philippines 4 Introduction THE Pre-SPANISH ERA ( UNTIL 1565 ) 0 THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public HealthSECOND EDITION 5 THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public Health SECOND EDITION THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e 6 Public HealthSECOND EDITION Introduction THE Pre-SPANISH ERA ( UNTIL 1565 ) 0 7 THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public Health SECOND EDITION Crispinita A. Valdez OVERALL PROJECT DIRECTOR Charity L. Tan EDITOR Celeste Coscoluella Edgar Ryan Faustino WRITERS Albert Labrador James Ona Edwin Tuyay Ramon Cantonjos Paquito Repelente PHOTOGRAPHERS Mayleen V. Aguirre Aida S. Aracap Rosy Jane Agar-Floro Dr. Aleli Annie Grace P. Sudiacal Mariecar C. -

Transnational Bataan Memories

TRANSNATIONAL BATAAN MEMORIES: TEXT, FILM, MONUMENT, AND COMMEMORATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES DECEMBER 2012 By Miguel B. Llora Dissertation Committee: Robert Perkinson, Chairperson Vernadette Gonzalez William Chapman Kathy Ferguson Yuma Totani Keywords: Bataan Death March, Public History, text, film, monuments, commemoration ii Copyright by Miguel B. Llora 2012 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank all my committee members for helping me navigate through the complex yet pleasurable process of undertaking research and writing a dissertation. My PhD experience provided me the context to gain a more profound insight into the world in which I live. In the process of writing this manuscript, I also developed a deeper understanding of myself. I also deeply appreciate the assistance of several colleagues, friends, and family who are too numerous to list. I appreciate their constant support and will forever be in their debt. Thanks and peace. iv ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the politics of historical commemoration relating to the Bataan Death March. I began by looking for abandonment but instead I found struggles for visibility. To explain this diverse set of moves, this dissertation deploys a theoretical framework and a range of research methods that enables analysis of disparate subjects such as war memoirs, films, memorials, and commemorative events. Therefore, each chapter in this dissertation looks at a different yet interrelated struggle for visibility. This dissertation is unique because it gives voice to competing publics, it looks at the stakes they have in creating monuments of historical remembrance, and it acknowledges their competing reasons for producing their version of history. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AKLAN 535,725 ALTAVAS 23,919 Cabangila 1,705 Cabugao 1,708 Catmon

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aklan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AKLAN 535,725 ALTAVAS 23,919 Cabangila 1,705 Cabugao 1,708 Catmon 1,504 Dalipdip 698 Ginictan 1,527 Linayasan 1,860 Lumaynay 1,585 Lupo 2,251 Man-up 2,360 Odiong 2,961 Poblacion 2,465 Quinasay-an 459 Talon 1,587 Tibiao 1,249 BALETE 27,197 Aranas 5,083 Arcangel 3,454 Calizo 3,773 Cortes 2,872 Feliciano 2,788 Fulgencio 3,230 Guanko 1,322 Morales 2,619 Oquendo 1,226 Poblacion 830 BANGA 38,063 Agbanawan 1,458 Bacan 1,637 Badiangan 1,644 Cerrudo 1,237 Cupang 736 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aklan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Daguitan 477 Daja Norte 1,563 Daja Sur 602 Dingle 723 Jumarap 1,744 Lapnag 594 Libas 1,662 Linabuan Sur 3,455 Mambog 1,596 Mangan 1,632 Muguing 695 Pagsanghan 1,735 Palale 599 Poblacion 2,469 Polo 1,240 Polocate 1,638 San Isidro 305 Sibalew 940 Sigcay 974 Taba-ao 1,196 Tabayon 1,454 Tinapuay 381 Torralba 1,550 Ugsod 1,426 Venturanza 701 BATAN 30,312 Ambolong 2,047 Angas 1,456 Bay-ang 2,096 Caiyang 832 Cabugao 1,948 Camaligan 2,616 Camanci 2,544 Ipil 504 Lalab 2,820 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aklan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Lupit 1,593 Magpag-ong