Designing out Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calving Ease

Section D Thursday, February 16, 2017 www.thecarillon.com Manitoba Community Newspapers Association News that matters to people in southeastern Manitoba #1 AG SECTION 2015 Agriculture Now Love of animals matched FEATURE by love of music for STORY: Steinbach-area veterinarian See story on page 6D Less calving problems, stronger newborn calves, higher quality colostrum. Calving ease. Rite-Lix Maxi Block has Bioplex® organic trace minerals and Sel-Plex® organic Selenium for improved absorption, which helps health, immunity and mineral transfer to the fetus. Studies show Rite-Lix also has a more consistent intake across a greater percentage of the cow herd than conventional dry mineral. Better mineral status means less calving issues, less retained placenta, stronger newborn calves, higher quality colostrum, as well as a quicker breed-back. Want stress free calving? Rite-Lix works for that! MAXI BLOC AVAILABLE AT MASTERFEEDS DEALERS AND MILL LOCATIONS ACROSS WESTERN CANADA. SteinbachCarillonCalvingAD.indd 1 2017-02-13 12:05 PM 2D – The Carillon, Thursday, February 16, 2017 Steinbach, Man. www.thecarillon.com Dufresne couple welcomes shift from farm to Ag Days showcase being accepted when they sub- by Wes Keating mitted their resumes to Mani- T is rare to see an occupation toba Ag Days. become a welcome leisure They met the managers who Iactivity and just as rare to see were retiring and it became a leisure activity develop into a evident that co-chairing west- rewarding career option. ern Canada’s largest agricultural But for Jonothon and Chris- trade show and farming at the tine Roskos who farm north of same time would not work. -

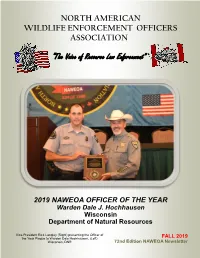

FALL 2019 Wisconsin, DNR 72Nd Edition NAWEOA Newsletter

NORTH AMERICAN WILDLIFE ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS ASSOCIATION “The Voice of Resource Law Enforcement” 2019 NAWEOA OFFICER OF THE YEAR Warden Dale J. Hochhausen Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Vice-President Rick Langley (Right) presenting the Officer of the Year Plaque to Warden Dale Hochhausen, (Left) FALL 2019 Wisconsin, DNR 72nd Edition NAWEOA Newsletter NAWEOA EXECUTIVE BOARD MEMBERS President Rick Langley [email protected] Arizona, US Vice President Kurt Henry [email protected] Manitoba , Canada Past President Shawn Farrell [email protected] New Brunswick, Canada Secretary/Treasurer Steve Beltran [email protected] Illinois, US Director Region 1 Brock Lockhart [email protected] Saskatchewan, Canada Director Region 2 Martin Thabault [email protected] Ontario, Canada Director Region 3 Josh Thibodeau [email protected] New Brunswick , Canada Director Region 4 Jason Sherwood [email protected] Wyoming, US Director Region 5 Jesse Gehrt [email protected] Kansas, US Director Region 6 Daniel Fagan [email protected] Florida, US Director Region 7 Larry Hergenroeder [email protected] Pennsylvania, US Webmaster Mike Reeder [email protected] Pennsylvania, US Conference Liaison Rich Cramer [email protected] Pennsylvania, US Welcome to the NAWEOA Online Store. Here you can purchase your N.A.W.E.O.A. membership, and renew or order IGW Magazine subscriptions. You do not have to have a PayPal account to purchase items. VISIT: NAWEOA.ORG SOUVENIR PATCHES AVAILABLE ← 2017 NAWEOA conference patches are available for purchase. The cost per patch (including shipping and handling) is $7.00 each USD. Patches are avail- able online at NAWEOA.org All 2018 and 2019 patches are sold out. -

Inaugural Excel Cups a Huge Success

INAUGURAL EXCEL CUPS A HUGE SUCCESS Curling Alberta’s inaugural Excel Cups were held November 29 to December 1 at the Okotoks Curling Club and the Saville Community Sports Centre. These exciting new events included the top U21 and U18 teams from Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia, and featured some outstanding games. The U21 Excel Cup in Okotoks produced two very deserving champions. On the female side, the Calgary team of Ryleigh Bakker (skip), Ashton Skrlik (third), Lisa Parent (second), Julianna Mackenzie (lead), and Jack Moss (coach) won the title and $1,500 with a 4-3 victory over the Abby Marks team from Edmonton. The Saskatoon team of Rylan Kleiter (skip), Trevor Johnson (third), Joshua Mattern (second), Matthieu Taillon (lead), and Dean Kleiter (coach) defeated the Ryan Jacques team from Edmonton 7-4 to take home the male title and $1,500. Meanwhile, at the U18 Cup at the Saville Centre, Saskatchewan teams took home both titles. The team of Madison Kleiter (skip), Emily Haupstein (third), Skylar Ackerman (second), Abbey Johnson (lead), and Clare Johnson of Saskatoon defeated the Claire Booth team from Red Deer 6-3 to take home $1,500 first prize and the female title. On the male side, the Saskatoon team of Daymond Bernath (skip), Nathen Pomedli (third), Logan Ede (second), Brayden Grindheim (lead), and Laurie Burrows (coach) earned $1,500 with their 5-3 victory over the Kyler Kurina team from Calgary. One of the unique features of the Excel Cups was that each included a Singles Skills Competition, which had each curler execute 12 different shots with the support of their regular sweepers and line-caller. -

2019 Conference Is to Be the Best from September 22-25, 2019

2019 Registration Brochure RBC Convention Centre Winnipeg, Manitoba SEPTEMBER PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONFERENCE 22-25 REGISTER JULY 1-AUG 19 2019 AND SAVE UP TO $105 LEARN FROM EMBRACE THE SHAPE THE THE PAST PRESENT FUTURE REGISTER BEFORE JUNE 30, 2019 AND SAVE UP TO $205 Canada’s Safety, Health and Environmental Practitioners SCHEDULE • KEYNOTES • SESSIONS • NETWORKING 2 EXHIBITIORS • PD COURSES • HOTEL • REGISTRATION LEARN FROM EMBRACE THE SHAPE THE THE PAST PRESENT FUTURE SEPTEMBER PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONFERENCE 22-25 MESSAGE FROM PRESIDENT & CONFERENCE CHAIR Each year Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) “Learn from the Past | Embrace the Present | Shape practitioners gather at the CSSE’s professional the Future” is the theme for 2019. National and development conference to challenge their thinking, international speakers were selected to bring their enhance their effectiveness on the job, and develop knowledge and expertise to this year’s conference. influential partnerships with other health and safety Sessions are designed to expand your knowledge colleagues from around the world! This year’s and provide practical insights on emerging issues. conference is being held in Winnipeg, Manitoba Our goal for the 2019 conference is to be the best from September 22-25, 2019. This is Canada’s “must professional development event you attend this year. attend” safety event! WE ARE PLEASED TO ANNOUNCE NEW INITIATIVES TO INCREASE THE VALUE OF ATTENDING THE CONFERENCE: • AGRICULTURAL STREAM – a series of workshops on Sunday and Monday focused -

Aeronautical Study

AERONAUTICAL STUDY NAVAID Modernization NAV CANADA Navigation & Airspace Level of Service 77 Metcalfe Street, 7th Floor Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5L6 August 2017 The information and diagrams contained in this Aeronautical Study are for illustrative purposes only and are not to be used for navigation. Aeronautical Study – NAVAID Modernization SIGNATURE PAGE Originated by: Brian Stockall – Manager, Level of Service and Aeronautical Studies Reviewed by: Boyd Barnes, Manager, Level of Service & Aeronautical Studies Reviewed by: Neil Bennett, National Manager, Level of Service Reviewed by: Jeff Cochrane, Director, Navigation and Airspace Reviewed By: Title: Signature: Date: Ben Girard Assistant Vice-President, Operational Support Reviewed By: Title: Signature: Date: Trevor Johnson Assistant Vice-President, Service Delivery Approved By: Title: Signature: Date: Rob Thurgur Vice President, Operations Aeronautical Study – NAVAID Modernization TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Purpose .................................................................................................................. 2 2.0 Background ............................................................................................................. 2 3.0 Analysis .................................................................................................................. 4 3.1 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Saskatchewan Curling Association (SCA) Board As Region Director for Over 12 Years and Also Curled Competitively

THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS AND FUNDING PARTNERS Table of Contents 2017 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AGENDA ........................................................................................... 3 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2016-2017 ............................................................................................................ 4 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR'S REPORT 2016-2017 ......................................................................................... 5 PROVINCIAL HIGH PERFORMANCE COACH’S REPORT 2016-2017 ...................................................... 7 PROGRAM/WORKSHOP REPORT 2016-2017 ........................................................................................... 8 MARKETING & MEMBER SERVICES REPORT 2016-2017 .................................................................... 11 CURLING CANADA DELEGATES REPORT 2016-2017 ........................................................................... 17 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE REPORT 2016-2017 ....................................................................................... 18 FINANCE & AUDIT REPORT 2016-2017 ................................................................................................... 20 GOVERNANCE AND POLICY REPORT 2016-2017 .................................................................................. 21 STRATEGIC PLANNING REPORT 2016-2017 .......................................................................................... 22 COMPETITION COMMITTEE REPORT 2016-2017 ................................................................................. -

2020 New Holland U21 Canadian Juniors Media

MEDIA GUIDE CURLING CANADA • NEW HOLLAND CANADIAN JUNIORS • MEDIA GUIDE 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EVENT INFORMATION BOARD OF GOVERNORS & NATIONAL STAFF 3 STATS, RECORDS & RESULTS FACT SHEET 4 JUNIOR MEN RECORDS 66 2021 WORLD JUNIORS QUALIFICATION 5 JUNIOR WOMEN RECORDS 73 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 6 MIXED DOUBLES WINNERS 80 2020 NEW HOLLAND CANADIAN JUNIORS ANNOUNCEMENT 7 NEW HOLLAND CANADIAN JUNIORS HISTORICAL RESULTS 80 NEW HOLLAND CANADIAN JUNIORS DRAW 9 PRACTICE SCHEDULE 10 AWARDS ALL-STAR TEAMS 81 MEN’S TEAM & PLAYER INFORMATION KEN WATSON SPORTSMANSHIP AWARD 84 MEN’S ROSTER 11 BALANCE PLUS FAIR PLAY AWARDS 85 MEN’S BIOS 12 ASHAM NATIONAL COACHING AWARD 86 ALBERTA 12 JOAN MEAD LEGACY AWARD 87 BRITISH COLUMBIA 1 14 BRITISH COLUMBIA 2 16 MANITOBA 1 17 MANITOBA 2 19 NEW BRUNSWICK 21 NEWFOUNDLAND & LABRADOR 23 NORTHERN ONTARIO 25 NORTHWEST TERRITORIES 27 NOVA SCOTIA 29 ONTARIO 31 PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND 32 QUEBEC 34 SASKATCHEWAN 36 WOMEN’S TEAM & PLAYER INFORMATION WOMEN’S ROSTER 38 WOMEN’S BIOS 39 ALBERTA 39 BRITISH COLUMBIA 41 MANITOBA 43 NEW BRUNSWICK 45 NEWFOUNDLAND & LABRADOR, 47 NORTHERN ONTARIO 49 NORTHWEST TERRITORIES 51 NOVA SCOTIA 53 NUNAVUT 55 ONTARIO 57 PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND 59 QUEBEC 61 SASKATCHEWAN 63 YUKON 64 CURLING CANADA • NEW HOLLAND CANADIAN JUNIORS • MEDIA GUIDE 2 BOARD OF GOVERNORS & NATIONAL STAFF CURLING CANADA 1660 Vimont Court Orléans, ON K4A 4J4 TEL: (613) 834-2076 FAX: (613) 834-0716 TOLL FREE: 1-800-550-2875 BOARD OF GOVERNORS John Shea, Chair Angela Hodgson, Governor Donna Krotz, Governor Amy Nixon, Governor George Cooke, -

DECEMBER 2012 GM’S Notes - Past, Present and Future (Ala Dickens “A Christmas Carol”!) by Lisa Sinnicks

"It came without ribbons! It came without tags! It came without packages, boxes or December bags!"... Then the Grinch thought of something he hadn't before! "Maybe Christmas," he 2012 thought, "doesn't come from a store. Maybe Christmas... perhaps... means a little bit more!" ~Dr. Seuss, How the Grinch Stole Christmas! Riverview Community Centre 90 Ashland Avenue Winnipeg MB R3L 1K6 RIVERVIEW Phone: 452-9944 Fax : 415-3779 www.riverviewcc.ca [email protected] REFLECTOR Breakfast with Santa December 8 10:30 am - 12:30 pm Details on page 4 Can You Volunteer? Read about Riverview Award Recipients! email pgs 7 & 19 [email protected] Editor’s Notes 2 Riverview & Norwood Babysitter's List 14 Inside Note From the President 3 Neighbourhood Party 8 Kid's Corner 14 SWSRC: Fall Prevention 3 Grands'n'More 9 Cool People, Cool Things: This November 11th, a poem 5 Bill Madder Field Update 10 Meet the Filmmaker 16 GM's Notes 6 Riverview Health Centre 11 Neighbourhood Christmas Issue Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Osborne South Biz Bulletin 11 Tour of 7 Artist's Studios 19 { Jubilee Medal 7 Grace Bible Church 13 WHO’S WHO EDITOR’S NOTES President Shared Space Design By Trevor Johnson Jino Distasio.......................................................475-4459 Past President n December of 2011, Londoners walked out into the traffic of Beverly Suek......................................................453-4350 IExhibition Road to share the street space equally with vehicles y Vice-President and cyclists. Previously this road had been more like an average t i Ryan Rolston......................................................889-0421 urban street in any large city in the world: cluttered and unwel- n Treasurer coming for pedestrians - even dangerous. -

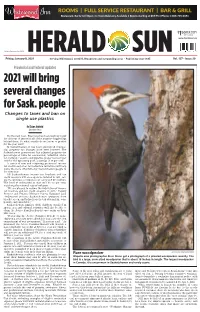

2021 Will Bring Several Changes for Sask. People Changes to Taxes and Ban on Single Use Plastics

Whitewood Inn Restaurant, Bar & Grill Open - In Town Deleivery Available j33199;!8ধ2+!;¤Wj,32'f¤ff¤ $150 PER COPY (GST included) www.heraldsun.ca Publications Mail Agreement No. 40006725 -YPKH`1HU\HY` Serving Whitewood, Grenfell, Broadview and surrounding areas • Publishing since 1893 =VS0ZZ\L Provincial and federal updates 2021 will bring several changes for Sask. people Changes to taxes and ban on single use plastics By Elaine Ashfield Grasslands News It’s the new year. Everyone has been waiting to put the old year of 2020 with all of the negative happenings behind them. So what exactly do we know or predict for the year 2021? In Saskatchewan, it has been announced commer- cial property tax changes have been lowered. The Saskatchewan government has adjusted property tax percentages of value for commercial, industrial, eleva- tor, railway, resource and pipeline properties to 85 per cent for the upcoming year, a savings of 15 per cent. A series of new and returning provincial income tax credits and other tax-reduction initiatives will help make life more affordable for Saskatchewan people in the new year. All Saskatchewan income tax brackets and tax credit amounts will once again be indexed in 2021, sav- ing the province’s taxpayers an estimated $15 million. The level of indexation in 2021 will be 1.0 per cent, matching the national rate of inflation. “We are pleased to resume the indexation of income tax brackets and tax credit amounts in 2021,” Deputy Premier and Finance Minister Donna Harpauer said. “Indexation protects Saskatchewan taxpayers from bracket creep, and helps keep the tax system fair, com- petitive and affordable.” Saskatchewan families with children enrolled in sports, arts and cultural activities will also be able to claim the Active Families Benefit once again on their 2021 taxes. -

00-Parade of Champions 2016

SaskTel Men Steve Laycock, Kirk Muyres, Colton Flasch, Dallan Muyres Lyle Muyres, Coach Saskatoon Nutana Curling Club Viterra Scotties Women Jolene Campbell, Ashley Howard, Callan Hamon, Ashley Williamson Russ Howard, Coach Regina Highland Curling Club Junior Men Jacob Hersikorn, Brady Kendel, Anthony Neufeld, Nicklas Neufeld Laurie Burrows, Coach Saskatoon Sutherland Curling Club Junior Women Kourtney Fesser, Karlee Korchinski, Krista Fesser, Renelle Humphreys James Malainey, Coach Saskatoon Nutana Curling Club Ramada Hotels, presented by Optimist Clubs of Saskatchewan, U18 Women’s Division Championship Team Rachel Erickson, Sarah Hoag, Kelly Kay, Jade Goebel Shane Kitz, Coach Maryfield Curling Club Ramada Hotels, Presented by Optimist Clubs of Saskatchewan, U18 Men’s Division Championship Team Rylan Kleiter, Trevor Johnson, Joshua Mattern, Matthiew Taillon Dean Kleiter, Coach Saskatoon Sutherland Curling Club Ramada Hotels, Presented by Optimist Clubs of Saskatchewan, U18 Men’s Division Designated Team Mitchell Dales, Dustin Mikush, Mitchell Schmidt, Braden Fleischhacker Verne Anderson, Coach Wadena Curling Club Ramada Hotels, Presented by Optimist Clubs of Saskatchewan, U18 Open Division Championship Team Connor Gronsdahl, Cole Macknak, Dalton Wenaus, Kohlton Booth Coach, Kevin Gronsdahl Assiniboia Curling Club Womens Provincial Club Champions Danette Tracey, Jade Ivan, Charla Moore, Lianne Cretin Weyburn Curling Club Mens Provincial Club Champions Kory Kohuch, David Kraichy, Wes Lang, David Schmirler Saskatoon Nutana Curling Club -

1998-99 Saskpower Northern

613 Park Street. Regina, Sask. S4N 5N1 Phone: (306) 780-9202 Fax: (306) 780-9404 Toll Free: 1-877-722-2875 e-mail: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 2, 2017 JIFFY LUBE JUNIOR MEN'S PROVINCIAL CURLING PLAYDOWN The twelve teams that have qualified for the 2016 - 2017 Jiffy Lube Junior Men's Provincial Curling Championship to be held at the Melfort Curling Club, January 4 – 8, 2017 are listed below. The Champion will represent Saskatchewan at the National Juniors to be held January 21 – 29, 2017 in Victoria, B.C.. Team 1 Saskatoon Sutherland Brayden Stewart, Tony Neufeld, Jared Latos, Andrew Hodgson, Coach Andrea McEwen Team 2 Saskatoon Nutana Mitchell Dales, Dustin Mikush, Mitchell Schmidt, Braden Fleischhacker, Coach Verne Anderson Team 3 Saskatoon Sutherland Rylan Kleiter, Trevor Johnson, Joshua Mattern, Matthieu Taillon, Coach Dean Kleiter Team 4 Saskatoon Sutherland Shawn Vereschagin, Gavin Steckler, Caid Brossart, Reid Pilkey, Coach Michael Vereschagin Team 5 Regina Callie Travis Tokarz, Drew Springer, Garrison Fox, Kevin Haines, Coach Tom Hamon Team 6 Saskatoon Sutherland Carson Ackerman, Tyler Camm, Andrew Derksen, Eric Westad, Coach Dwayne Yachiw Team 7 Saskatoon Nutana Chad Lang, Brett Lang, James Barkway, Daniel Mutlow, Coach Jim Wilson Team 8 Lumsden Sam Wills, Kentz Parker, Cole Regush, Riley Lloyd, Coach Stacy Lloyd Team 9 Regina Callie Austin Williamson, Tyson Williamson, Brandon McMullin, Brody Blackwell, Coach Derick Williamson Team 10 St. Walburg Jonathan Zuchotzki, Evan Schmidt, Sheldon Manners, Doug Sroka, -

2020 Annual General Meeting Report

Table of Contents PRESIDENT’S REPORT by Christy Walker ..........................................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR'S REPORT by Ashley Howard ........................................................................................................................3 GOVERNMENT AND POLICY REPORT by Helen Fornwald ................................................................................................................6 COMPETITION COMMITTEE REPORT by Bruce Korte .......................................................................................................................7 PARTICIPATION AND DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE REPORT by Jim Wilson ....................................................................................8 SOCIAL MEDIA UPDATE ....................................................................................................................................................................8 STRATEGIC PLANNING COMMITTEE REPORT by Michael Dudar ......................................................................................................9 VOLUNTEER SCREENING COMMITTEE REPORT by Darrell Brandt ...................................................................................................9 HIGH PERFORMANCE REPORT by Pat Simmons ............................................................................................................................ 10 MEMBERSHIP COORDINATOR REPORT by Daniel Selke ...............................................................................................................