Giant River Prawn (Macrobrachium Rosenbergii) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductive Potential of Four Freshwater Prawn Species in the Amazon Region

Invertebrate Reproduction & Development ISSN: 0792-4259 (Print) 2157-0272 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tinv20 Reproductive potential of four freshwater prawn species in the Amazon region Leo Jaime Filgueira de Oliveira, Bruno Sampaio Sant’Anna & Gustavo Yomar Hattori To cite this article: Leo Jaime Filgueira de Oliveira, Bruno Sampaio Sant’Anna & Gustavo Yomar Hattori (2017) Reproductive potential of four freshwater prawn species in the Amazon region, Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, 61:4, 290-296, DOI: 10.1080/07924259.2017.1365099 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2017.1365099 Published online: 21 Aug 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 43 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tinv20 INVERTEBRATE REPRODUCTION & DEVELOPMENT, 2017 VOL. 61, NO. 4, 290–296 https://doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2017.1365099 Reproductive potential of four freshwater prawn species in the Amazon region Leo Jaime Filgueira de Oliveira†, Bruno Sampaio Sant’Anna and Gustavo Yomar Hattori Instituto de Ciências Exatas e Tecnologia (ICET), Universidade Federal do Amazonas (UFAM), Itacoatiara, Brazil ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The bioecology of freshwater prawns can be understood by studying their reproductive biology. Received 1 June 2017 Thus, the aim of this paper was to determine and compare the reproductive potential of four Accepted 4 August 2017 freshwater caridean prawns collected in the Amazon region. For two years, we captured females KEYWORDS of Macrobrachium brasiliense, Palaemon carteri, Pseudopalaemon chryseus and Euryrhynchus Caridea; Euryrhynchidae; amazoniensis from inland streams in the municipality of Itacoatiara (AM). -

Economics of Freshwater Prawn Farming in the United States

SRAC Publication No. 4830 VI November 2005 PR Economics of Freshwater Prawn Farming in the United States Siddhartha Dasgupta1 Freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium Alabama with 60 acres. There are 20,000 eggs, which hatch into rosenbergii) farming in the United also a few prawn farms in prawn larvae in 3 weeks. Newly States has been predominantly a Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, hatched larvae are kept in brack- small-scale aquaculture industry. Indiana, Louisiana and Ohio. ish water where they need pro- The U.S. industry started in During the 1980s and 1990s, 0.2 tein-rich feed such as zooplank- Hawaii in the 1960s, followed by to 0.4 million pounds of prawns ton. After 22 to 30 days, post- South Carolina in the 1970s and per year were produced in the larvae can be stocked in freshwa- Mississippi in the 1980s. Early U.S. The crop had an annual ter. The post-larvae are usually attempts at prawn culture were wholesale value of $0.89 million nursed for at least 30 more days. hampered by lack of seed stock to $2.54 million and the prices Then the juveniles are ready to be and problems in marketing the for whole prawns paid by proces- stocked into ponds for grow-out to end product. During the 1980s sors and other wholesale buyers adult prawns. and 1990s, researchers developed ranged from $4 to $7 per pound. The parameters of prawn produc- several elements important for the The price of Gulf of Mexico tion are industry’s growth, such as marine shrimp (tails only) • stocking density (number of improved hatchery and nursery declined from $7.00 per pound to technology, pond culture methods, juveniles stocked per acre of $4.50 per pound from 1995 to water), and post-harvest handling proto- 2002, which corresponded to an cols for quality control and prod- approximate price range of $2.25 • age of seed at stocking, uct preservation. -

Palaemonidae, Macrobrachium, New Species, Anchia- Line Cave, Miyako Island, Ryukyu Islands

Zootaxa 1021: 13–27 (2005) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1021 Copyright © 2005 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new stygiobiont species of Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Deca- poda: Caridea: Palaemonidae) from an anchialine cave on Miyako Island, Ryukyu Islands TOMOYUKI KOMAI1 & YOSHIHISA FUJITA2 1 Natural History Museum and Institute, Chiba, 955-2 Aoba-cho, Chuo-ku, Chiba, 260-8682 Japan ([email protected]) 2 University Education Center, University of the Ryukyus, 1 Senbaru, Nishihara-cho, Okinawa, 903-0213 Japan ([email protected]) Abstract A new stygiobiont species of the caridean genus Macrobrachium Bate, 1864 is described on the basis of two male specimens from an anchialine cave on Miyako Island, southern Ryukyu Islands. The new species, M. miyakoense, is compared with other five stygiobiont species of the genus char- acterized by a reduced eye, i.e. M. cavernicola (Kemp, 1924), M. villalobosi Hobbs, 1973, M. acherontium Holthuis, 1977, M. microps Holthuis, 1978, and M. poeti Holthuis, 1984. It is the first representative of stygiobiont species of Macrobrachium from East Asian waters. Key words: Crustacea, Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae, Macrobrachium, new species, anchia- line cave, Miyako Island, Ryukyu Islands Introduction There are few stygiobiont species of the palaemonid genus Macrobrachium Bate, 1864 in the world, although the genus is one of the most speciose caridean genera, abundant in tropical fresh waters (Chace & Bruce, 1993). Holthuis (1986) listed six stygiobiont species of Macrobrachium, together with additional 12 stygiophile or stygoxene species. The six stygiobiont species are: M. cavernicola (Kemp, 1924) from Siju Cave in Assam, India (Kemp, 1924); M. -

1 Assessment of Gear Efficiency for Harvesting Artisanal Giant Freshwater Prawn

Assessment of Gear Efficiency for Harvesting Artisanal Giant Freshwater Prawn (Macrobrachium Rosenbergii de Man) Fisheries from the Sundarbans Mangrove Ecosystem in Bangladesh Biplab Kumar Shaha1, Md. Mahmudul Alam2*, H. M. Rakibul Islam3, Lubna Alam4, Alokesh Kumar Ghosh5, Khan Kamal Uddin Ahmed6, Mazlin Mokhtar7 1Fisheries and Marine Resource Technology Discipline, Khulna University, Bangladesh 2Doctoral Student, Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), National University of Malaysia (UKM), Malaysia 3Scientific Officer, Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute, Shrimp Research Station, Bagerhat, Bangladesh 4 Research Fellow, Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), National University of Malaysia (UKM), Malaysia 5Assistant Professor, Fisheries and Marine Resource TechnologyDiscipline, Khulna University, Bangladesh 6Chief Scientific Officer, Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute. Shrimp Research Station, Bagerhat, Bangladesh 7Professor, Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), National University of Malaysia (UKM), Malaysia Citation Reference: Shaha, B.K., Alam, M.M., Islam, H.M.R., Alam, L., Ghosh, A.K., Ahmed, K.K.U., and Mokthar, M. 2014. Assessment of Gear Efficiency for Harvesting Artisanal Giant Freshwater Prawn (Macrobrachium Rosenbergii De Man) Fisheries from the Sundarbans Mangrove Ecosystem in Bangladesh. Research Journal of Fisheries and Hydrobiology, 9(2): 1126-1139. http://www.aensiweb.com/old/jasa/2- JASA_February_2014.html This is a pre-publication copy. The published article is copyrighted -

FINANCIAL ANALYSIS of FRESHWATER PRAWN in MIXED FARMS in SELECTED PROVINCES of THAILAND by Chao Tiantong, B.Sc

FINANCIAL ANALYSIS OF FRESHWATER PRAWN IN MIXED FARMS IN SELECTED PROVINCES OF THAILAND by Chao Tiantong, B.Sc.(Agr.), Dip. Agr. Sc. (Post) A sub-thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Agricultural Development Economics in the Australian National University August, 1981 ii DECLARATION Except where otherwise indicated, this sub-thesis is my own work. August, 1981 C. Tiantong ( LIBRAS iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The present sub-thesis would not have been completed without the assistance and support of a number of people. Dr Barry Shaw and Dr David Evans spent a lot of their precious time supervising me on this thesis. At all times they could be approached for discussion. Without their valuable advice, constructive ideas and willingness to correct my English this thesis would have taken a much longer time to finish. In fact, they were more than supervisors and I can hardly express the extent of my gratitude to them. The MADE Convener, Dr Dan M. Etherington was very helpful in guiding the analysis of the data and the provision of related materials. His understanding of the problems involved in writing a thesis allowed me sufficient time to complete my work. To him, I wish to express my sincere thanks. The thesis also would not have been finished without financial support from the Australian Development Assistance Bureau (ADAB). My thanks to ADAB and all the officers involved in students' affairs. Dusit Sirirote, Wuttikorn Masaphand, Dr Sumlit Tiandum and Tek Kowalski, the first three from OAE and the latter from the Australian Embassy in Bangkok, can never be forgotten because of their help in supplying data and related information. -

Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae) from the Highlands of South Vietnam

A NEW FRESHWATER PRAWN OF THE GENUS MACROBRACHIUM (DECAPODA, CARIDEA, PALAEMONIDAE) FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF SOUTH VIETNAM BY NGUYEN VAN XUÂN1) Faculty of Fisheries, University of Agriculture and Forestry, Thu Duc, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam ABSTRACT A new species of the genus Macrobrachium, M. thuylami, was discovered in the highlands of South Vietnam. A description, illustrations, and notes on habitat and economic importance of this species are provided. RÉSUMÉ Une nouvelle espèce du genre Macrobrachium, M. thuylami a été découverte dans une région montagneuse du Sud Vietnam. Une description et des illustrations, ainsi que des notes sur l’habitat et l’importance économique de cette espèce sont fournies. INTRODUCTION During a trip in Duc Lap, a district of Daklak Province about 300 km northeast of Ho Chi Minh City, we had an opportunity to buy some prawns of the genus Macrobrachium. These seem to belong to an as yet undescribed species, and this is described below. The new species, Macrobrachium thuylami, is characteristic in having the antepenultimate segment of the third maxilliped serrate at the distal half of the outer margin. Notes on habitat and economic importance are provided. The abbreviation tl. is used for total length, measured from the tip of the rostrum to the tip of the telson in the fully stretched specimen; cl. is used for carapace length excluding the rostrum. The material discussed here is deposited in the collection of the National Museum of Natural History (RMNH), Leiden, Netherlands. For identification of the prawn, papers of Holthuis (1950), Naiyanetr (1993), and Xuân (2003) were used. -

Macrobrachium Rosenbergii (De Man, 1879)

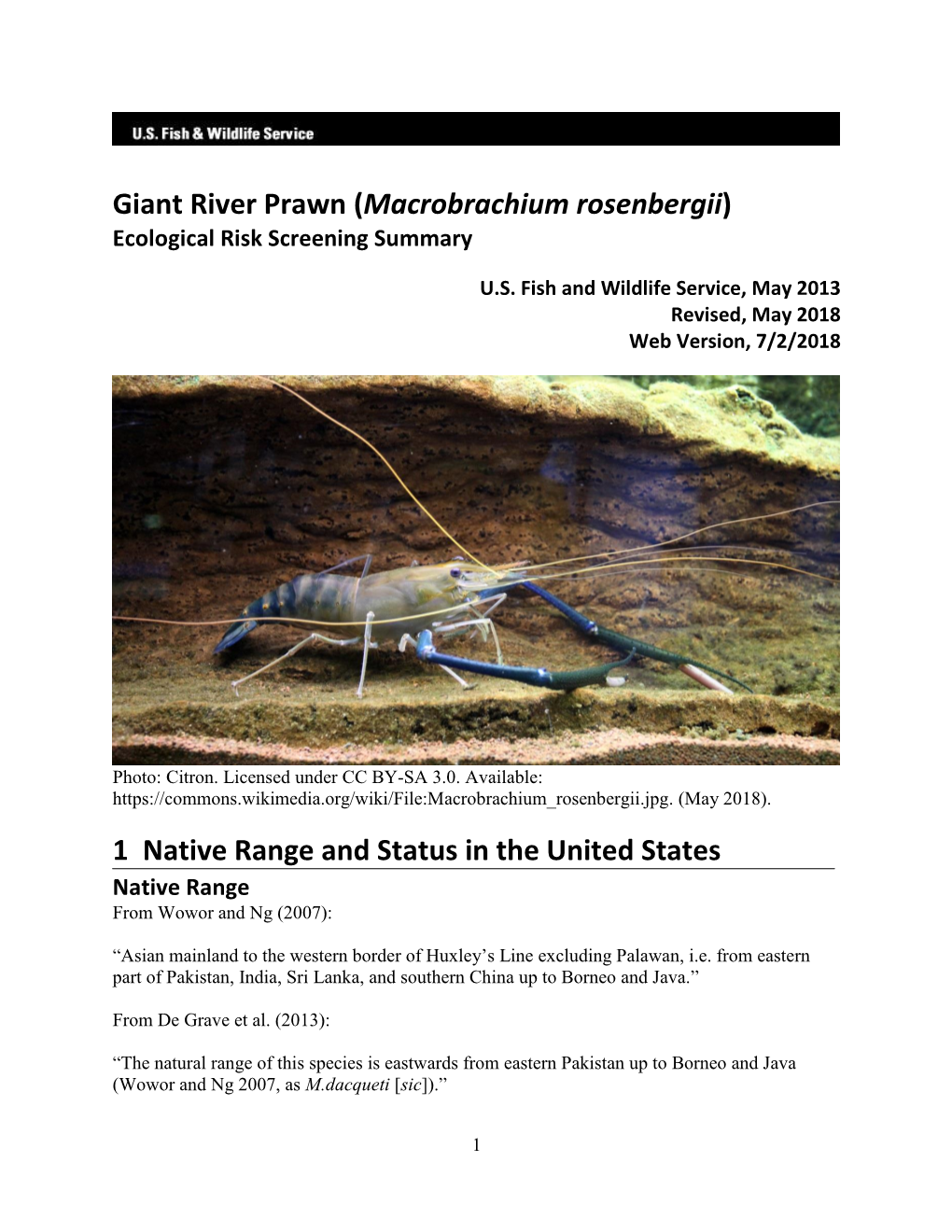

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fisheries and for a world without hunger Aquaculture Department Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man, 1879) I. Identity V. Status And Trends a. Biological Features VI. Main Issues b. Images Gallery a. Responsible Aquaculture Practices II. Profile VII. References a. Historical Background a. Related Links b. Main Producer Countries c. Habitat And Biology III. Production a. Production Cycle b. Production Systems c. Diseases And Control Measures IV. Statistics a. Production Statistics b. Market And Trade Identity Macrobrachium rosenbergii De Man, 1879 [Palaemonidae] FAO Names: En - Giant river prawn, Fr - Bouquet géant, Es - Langostino de río View FAO FishFinder Species fact sheet Biological features Males can reach total length of 320 mm; females 250 mm. Body usually greenish to brownish grey, sometimes more bluish, darker in larger specimens. Antennae often blue; chelipeds blue or orange. 14 somites within cephalothorax covered by large dorsal shield (carapace); carapace smooth and hard. Rostrum long, normally reaching beyond antennal scale, slender and somewhat sigmoid; distal part curved somewhat upward; 11-14 dorsal and 8-10 ventral teeth. Cephalon contains eyes, antennulae, antennae, mandibles, maxillulae, and maxillae. Eyes stalked, except in first larval stage. Thorax contains three pairs of maxillipeds, used as mouthparts, and five pairs of pereiopods (true legs). First two pairs of pereiopods chelate; each pair of chelipeds equal in size. Second chelipeds bear numerous spinules; robust; slender; may be excessively long; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department chelipeds equal in size. Second chelipeds bear numerous spinules; robust; slender; may be excessively long; mobile finger covered with dense, though rather short pubescence. -

Comparing Environmental Impacts of Native and Introduced Freshwater Prawn Farming in Brazil and the Influence of Better Effluent

Aquaculture 444 (2015) 151–159 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Aquaculture journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aqua-online Comparing environmental impacts of native and introduced freshwater prawn farming in Brazil and the influence of better effluent management using LCA☆ Alexandre Augusto Oliveira Santos a,e,⁎, Joël Aubin b,c, Michael S. Corson b,c, Wagner C. Valenti a,d, Antonio Fernando Monteiro Camargo a,e a Centro de Aquicultura da UNESP (CAUNESP), Jaboticabal, SP, Brazil b INRA, UMR 1069 Sol Agro et hydrosystème Spatialisation, F-35000 Rennes, France c Agrocampus Ouest, F-35000 Rennes, France d São Paulo State University, UNESP, Coastal campus of São Vicente, São Vicente, SP, Brazil e Universidade Estadual Paulista — UNESP, Departamento de Ecologia, IB, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil article info abstract Article history: Concern about environmental impacts of aquaculture and its interaction with natural resources is increasing. Received 9 July 2013 Thus, it is important for new production systems to use practices that reduce environmental impacts, such as Received in revised form 12 February 2015 choosing to farm native species from a region's biological diversity and adopting better effluent management. Accepted 6 March 2015 This study aimed to estimate and compare environmental impacts of tropical freshwater prawn farming systems Available online 13 March 2015 based either on the introduced species Macrobrachium rosenbergii (giant river prawn) or the native species Keywords: Macrobrachium amazonicum (Amazon river prawn). The two hypothetical systems were compared using life fi Macrobrachium rosenbergii cycle assessment (LCA) with the impact categories climate change, eutrophication, acidi cation, energy use, Macrobrachium amazonicum net primary production use, surface use and water dependence. -

Integrated Freshwater Prawn Farming: State-Of- The-Art and Future Potential

Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture ISSN: 2330-8249 (Print) 2330-8257 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/brfs21 Integrated Freshwater Prawn Farming: State-of- the-Art and Future Potential Helcio L. A. Marques, Michael B. New, Marcello Villar Boock, Helenice Pereira Barros, Margarete Mallasen & Wagner C. Valenti To cite this article: Helcio L. A. Marques, Michael B. New, Marcello Villar Boock, Helenice Pereira Barros, Margarete Mallasen & Wagner C. Valenti (2016) Integrated Freshwater Prawn Farming: State-of-the-Art and Future Potential, Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture, 24:3, 264-293, DOI: 10.1080/23308249.2016.1169245 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2016.1169245 Published online: 20 Apr 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=brfs21 Download by: [Dr Wagner Valenti] Date: 21 April 2016, At: 11:00 REVIEWS IN FISHERIES SCIENCE & AQUACULTURE 2016, VOL. 24, NO. 3, 264–293 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2016.1169245 Integrated Freshwater Prawn Farming: State-of-the-Art and Future Potential Helcio L. A. Marquesa, Michael B. Newb, Marcello Villar Boocka, Helenice Pereira Barrosc, Margarete Mallasenc,y, and Wagner C. Valentid aAquaculture Center, Fisheries Institute, Sao Paulo State Secretariat of Agriculture and Food Supply, S~ao Paulo, Brazil; bFreshwater Prawn Farming Research Group, CNPq, Brazil, Marlow, Bucks, UK; cCenter for Continental Fish, Fisheries Institute, Sao Paulo State Secretariat of Agriculture and Food Supply, S~ao Paulo, Brazil; dBiosciences Institute and CAUNESP, CNPq., S~ao Paulo State University UNESP, S~ao Paulo, Brazil ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Integrated aquaculture can be defined as aquaculture systems sharing resources with other freshwater prawns; activities, commonly agricultural, agroindustrial, and infrastructural. -

The Ohio Shrimp, Macrobrachium Ohione (Palaemonidae), in the Lower Ohio River of Illinois

Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science received 11/19/01 (2002), Volume 95, #1, pp. 65-66 accepted 1/2/02 The Ohio Shrimp, Macrobrachium ohione (Palaemonidae), in the Lower Ohio River of Illinois William J. Poly1 and James E. Wetzel2 1Department of Zoology and 2Fisheries and Illinois Aquaculture Center Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois 62901 ABSTRACT Until about the 1930s, the Ohio shrimp, Macrobrachium ohione, was common in the Mississippi River between Chester and Cairo, and also occurred in the Ohio and lower Wabash rivers bordering southern Illinois, but since then, the species declined sharply in abundance. Two specimens were captured in May 2001 from the Ohio River at Joppa, Massac Co., Illinois, and represent the first M. ohione collected in the Ohio River in over 50 years. The Ohio shrimp, Macrobrachium ohione, was described from specimens collected in the Ohio River at Cannelton, Indiana (Smith, 1874) and occurs in the Mississippi River basin, Gulf Coast drainages, and also in some Atlantic coast drainages from Virginia to Georgia (Hedgpeth, 1949; Holthuis, 1952; Hobbs and Massmann, 1952). The Ohio shrimp formerly was abundant in the Mississippi River as far north as Chester, Illinois (and possibly St. Louis, Missouri) and in the Ohio River as far upstream as southeastern Ohio (Forbes, 1876; Hay, 1892; McCormick, 1934; Hedgpeth, 1949) but has declined in abundance drastically after the 1930s (Page, 1985). There has been only one record of the Ohio shrimp in the Wabash River bordering Illinois dated 1892, and the only record from the Ohio River of Illinois was from Shawneetown in southeastern Illinois (Hedg- peth, 1949; Page, 1985). -

Nature and Science 2018;16(1)

Nature and Science 2018;16(1) http://www.sciencepub.net/nature Operational System and Catch Composition of Charberjal (Fixed Net) in Tetulia River and its Impact on Fisheries Biodiversity in the Coastal Region of Bangladesh Md. Moazzem Hossain1, Masum Billah2, Md. Belal Hossen3, Md. Hafijur Rahman4 1Department of Fisheries Management, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali-8602, Bangladesh 2Department of Aquaculture, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali-8602, Bangladesh 3Department of Fisheries Biology and Genetics, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali- 8602, Bangladesh 4Department of Fisheries Management, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Abstract: An investigation was carried out to acquire the knowledge regarding charberjal operation system in Tetulia River and its impact on fisheries biodiversity in the coastal region of Bangladesh over a period of 6 months between July and December 2016. Combination of questionnaire interview, focus group discussions and crosscheck interviews were accomplished with key informants during data collection. Charberjal is operated in the shoreline of rivers, submerged chars and inundated agriculture land including tiny canals all over the coastal region of Bangladesh. A total of 80 species including finfish, freshwater prawn, crabs and mollusk was recorded under 22 families including 38 SIS and 26 threatened species during the study period. The recorded species was 60 finfish, 14 prawn, 4 mollusk and 2 crabs. Among the finfish rui, bata, mullet, khorsula and poa were the dominant species while aire, boal, bacha, ramsosh and tengra were the foremost species among catfish. Moreover, Macrobrachium rosenbargii was the most prevailing species among fresh water prawn while bele, phasa, puti, shol, dimua chingri and SIS were the most leading species among others. -

Subsector Assessment of the Nigerian Shrimp and Prawn Industry

Subsector Assessment of the Nigerian Shrimp and Prawn Industry Prepared by: Chemonics International Incorporated 1133 20th Street, NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 955-3300 Prepared for: The United States Agency for International Development (USAID)/Nigeria RAISE IQC, contract no. PCE-I-00-99-00003-00 Agricultural Development Assistance in Nigeria Task Order No. 812 November 2002 FOREWORD Under the Rural and Agricultural Incomes with a Sustainable Environment (RAISE) IQC, Chemonics International and its Agricultural Development Assistance in Nigeria (ADAN) project are working with USAID/Nigeria and the Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (GON) to stimulate Nigeria’s economic growth through increased competitiveness in the world market. A key component of this effort centers on determination of specific agricultural products with the greatest potential for increasing foreign exchange and employment. ADAN specifically targets increased agricultural commodity production and exports, and seeks to boost domestic sales as well through opportunistic ‘fast track’ activities, which are loosely based on development of networks and linkages to expedite trade. At a stakeholders’ conference in Abuja, Nigeria in January 2002, participants identified five Nigerian products that held the greatest potential for export growth. Chemonics/ADAN was charged with conducting sub-sector assessments of these products, and then developing industry action plans (IAPs) for those that indicated sufficient market opportunities. The following sub-sector assessment examines market trends, opportunities and constraints, both international and domestic; production and processing requirements; operating environment issues; and recommendations to address the needs of the Nigerian industries. A separate IAP provides a strategic framework for actions, which the Nigerian and international private sector, Nigerian government, and donors should undertake to improve the viability of these industry clusters.