Back to the Parlour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

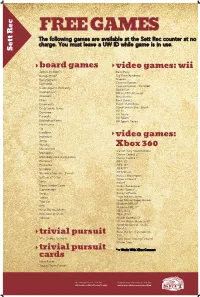

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Exploring 3D Gestural Interfaces for Music Creation in Video Games

Exploring 3D Gestural Interfaces for Music Creation in Video Games Jared N. Bott James G. Crowley Joseph J. LaViola Jr. University of Central Florida University of Central Florida University of Central Florida School of EECS School of EECS School of EECS Orlando, Florida 32816 USA Orlando, Florida 32816 USA Orlando, Florida 32816 USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT interest. These games offer the ability to simulate playing In recent years the popularity of music and rhythm-based music by using custom input devices designed to emulate the games has experienced tremendous growth. However almost instrument being played. Although it has been shown that all of these games require custom hardware to be used as in- such props can lead to a more immersive experience [7], these put devices, and these devices control only one or two similar input devices represent an additional investment required of instruments. In this paper we describe One Man Band, a the player. Furthermore while these games may give the prototype video game for musical expression that uses novel player the feeling of actually playing an instrument, there 3D spatial interaction techniques using accelerometer-based is almost no opportunity for individual musical expression. motion controllers. One Man Band provides users with 3D Instead, the user is relegated to using the input device to gestural interfaces to control both the timing and sound of trigger a predefined sequence of notes. Thus, most games of the music played, with both single and collaborative player the genre are more about matching rhythms than actually modes. -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2008 (Briefing Date: 2009/1/30) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2005 FY3/2006 FY3/2007 FY3/2008 FY3/2009 Apr.-Dec.'04 Apr.-Dec.'05 Apr.-Dec.'06 Apr.-Dec.'07 Apr.-Dec.'08 Net sales 419,373 412,339 712,589 1,316,434 1,536,348 Cost of sales 232,495 237,322 411,862 761,944 851,283 Gross margin 186,877 175,017 300,727 554,489 685,065 (Gross margin ratio) (44.6%) (42.4%) (42.2%) (42.1%) (44.6%) Selling, general, and administrative expenses 83,771 92,233 133,093 160,453 183,734 Operating income 103,106 82,783 167,633 394,036 501,330 (Operating income ratio) (24.6%) (20.1%) (23.5%) (29.9%) (32.6%) Other income 15,229 64,268 53,793 37,789 28,295 (of which foreign exchange gains) (4,778) (45,226) (26,069) (143) ( - ) Other expenses 2,976 357 714 995 177,137 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) (174,233) Income before income taxes and extraordinary items 115,359 146,694 220,713 430,830 352,488 (Income before income taxes and extraordinary items ratio) (27.5%) (35.6%) (31.0%) (32.7%) (22.9%) Extraordinary gains 1,433 6,888 1,047 3,830 98 Extraordinary losses 1,865 255 27 2,135 6,171 Income before income taxes and minority interests 114,927 153,327 221,734 432,525 346,415 Income taxes 47,260 61,176 89,847 173,679 133,856 Minority interests -91 -34 -29 -83 35 Net income 67,757 92,185 131,916 258,929 212,524 (Net income ratio) (16.2%) (22.4%) (18.5%) (19.7%) (13.8%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Alignment to AASL's Standards for the 21St Century Learner

Game Profile: Game Title: Wii Music ESRB Rating: E (Everyone) Genre: Simulation Grades: K-12 Peripherals Required: 1- 4 Wii Remotes and 1-4 Wii Nunchucks Peripherals Optional: Wii Balance Board Number of Players: 1- 4 Cooperative Multiplayer Game Summary: In Wii Music, the player uses both motions and button presses on the Wii Remote and Nunchuck to control a band of up to four Miis. Unlike other music games, Wii Music does not require the player to press specific buttons at certain times but only requires the player to move the Wii Remote and Nunchuck as if he or she were playing the instruments. Sixty-six playable instruments are available in the single and multiplayer modes, including the violin, cowbell, clarinet, harmonica, piano, guitar, trumpet, harp, shamisen, maracas, sitar and marimba, as well as unconventional instruments such as dog and cat sounds and pseudo doo-wop vocals. In addition, the Wii Balance Board can be utilized to play the drums. Wii Music features 52 songs that consist of a combination of Classical and Traditional songs, 7 songs from Nintendo games and 15 licensed songs. Alignment to AASL’s Standards for the 21st Century Learner: 1.1.9 Collaborate with others to arrange and create music within specified guidelines of the game engine. 3.2.3 Demonstrate teamwork by working to perform on a variety of traditional and nontraditional instruments with others on a diverse repertoire of music. 4.1.5 Learners will relate their critical assertions about Wii Music to its aesthetic, structural, acoustic and psychological qualities. Students will use concepts based on the structure of Wii Music’s content and context to relate music to other broad areas of knowledge. -

A Gestural Interface in a Computer-Based Conducting System

A Gestural Interface in a Computer-based Conducting System A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science In Computer Science University of Regina By Lijuan Peng Regina, Saskatchewan October, 2008 ©Copyright 2008: L. Peng Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-55050-2 Our file Notre inference ISBN: 978-0-494-55050-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

A Virtual Instrument Using the Wii Remote

Proceedings of the 2010 Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME 2010), Sydney, Australia Wiiolin: a virtual instrument using the Wii remote Jace Miller & Tracy Hammond Sketch Recognition Lab Department of Computer Science & Engineering Texas A&M University {jacemiller, hammond}@tamu.edu ABSTRACT being played. The console gaming industry is experiencing a revolution in terms of user control, and a large part to Nintendo’s introduction of the Wii remote. The online open source development community has embraced the Wii remote, integrating the inexpensive technology into numerous applications. Some of the more interesting applications demonstrate how the remote hardware can be leveraged for nonstandard uses. In this paper we describe a new way of interacting with the Wii remote and sensor bar to produce music. The Wiiolin is a virtual instrument which can mimic a violin or cello. Sensor bar motion relative to the Wii remote and button presses are analyzed in real-time to generate notes. Our design is novel in that it involves the remote’s infrared camera and sensor bar as an integral part of music production, allowing users to change notes by simply altering the angle of their wrist, and henceforth, bow. The Wiiolin introduces a more realistic way of instrument interaction than other attempts that rely on button presses and accelerometer data alone. Figure 1: The orientation of the Wii remote determines whether the Wiiolin performs as a violin or cello. Keywords Wii remote, virtual instrument, violin, cello, motion 2. RELATED WORK recognition, human computer interaction, gesture recognition. A new genre of video games based on music production through instrument simulation was created with the release of 1. -

Exploring Middle School Mathematics with Nintendo Wii® NCTM Hartford, CT 2012

Exploring Middle School Mathematics with Nintendo Wii® NCTM Hartford, CT 2012 Christina Gawlik, Ph.D [email protected] Saint Xavier University Description: Engaging students in meaningful and fun mathematics can be accomplished using the Nintendo Wii™ through interdisciplinary units and differentiated instruction for grades 6-8. Come participate in lessons using the Wii™, discussion of managing all class sizes, diverse learners, teachable moments, and preparing students for high stakes tests. Lesson 1 – The Baseball Investigation One student at a time will practice hitting 10 consecutive baseballs. Awaiting students will cheer on their classmates and record data such as distance, speed, and type of ball hit. Analysis of data will include determining the percentage of each type of ball hit (foul balls, base hits, home runs, strikes), and create a circle graph representing the class data. Moreover, students will determine the average speed of balls hit per person and as a class. Lesson 2 – The Power Throw Bowling Investigation Students will bowl 10 rounds within the Power Throw training session, where the number of pins increases each round. Students will describe and create an expression for the pattern of increasing pins, as well as predict outcomes and calculate the maximum possible score. Data will later be transferred into scatter plots and line plots. Lesson 3 – The Ball Return Tennis Investigation Students will record the total number of balls returned during the training session called Returning Balls. Class data will be analyzed to determine central tendencies, and five-number summary to create a box-and-whisker and line plots. Additional Lesson Titles Lesson 4 – The Tennis Tournament Investigation Lesson 5 – The Golf Game Investigation Lesson 6 – The Scientific Experiment Investigation The lessons presented are available in the book called, Investigating Middle School Mathematics: Classroom Lessons Using Wii Sports® by Christina Gawlik. -

Bewegen Met Exergames Ik Speel Mee !

Tips Speel voldoende vaak, intensief en lang (bv. 3 keer per week, gedurende 1 uur) Stretch voor en na het Bewegen met gamen en las regelmatig een rustpauze in (om overbe- exergames lastingsletsels te voorkomen) Drink regelmatig een glas water en eet geen ongezonde snacks tijdens het spelen Bekijk de veiligheidsvoor- schriften van de consoles (bv. voldoende afstand houden t.a.v. scherm, ob- stakels verwijderen) Er is een groot aanbod games (geef verveling geen Ik speel mee ! kans!) Wat zijn exergames? Energieverbruik Voordelen Exergames zijn videogames die je speelt Als je exergames speelt, verbruik je gemiddeld Je leert verschillende sporten kennen door te bewegen. Exergames vragen dus 3 à 4 MET per minuut (= matige fysieke Door exergames te spelen verbruik je meer een fysieke inspanning. inspanning). Echte sporten verbruiken wel meer energie dan exergamen. energie dan door zittend te gamen of tv te Je gebruikt je lichaam in plaats van een kijken ‘klassieke’ controller. Je kan ook Gewone attributen gebruiken (bv. dansmat, Spel Wii Kinect fysieke activiteiten Je kan spelen op verschillende moeilijk- baseball bat, fiets,…). heidsniveaus (beginner-gevorderde-expert) dansen 5.9 5.6 Fietsen 15 km/h Exergames kan je spelen op verschillende boksen 6.1 6.7 (5,8 MET) Je krijgt feedback en verbetert op die spelconsoles (bv. Microsoft Kinect, bowlen 4.4 3.6 Wandelen aan manier je vaardigheden Nintendo Wii, Playstation Move...). tennis 4.2 4.4 4,5 km/h Je kan je prestaties bijhouden baseball 3.7 4.1 (4,8 MET) Er bestaan heel wat soorten exergames. golf 3.5 2.9 Yoga (3 MET) Je kan zelf kiezen wanneer je speelt, wat je Hieronder vind je een overzicht van spelt en met wie verschillende sport exergames: Je verbruikt meer energie als je zowel je Je kan ook kiezen voor korte games boven– als onderlichaam gebruikt tijdens het Wii Playstation Kinect spelen (bv. -

Conceptualización De Un Videojuego Y Creación De Su Interfaz Gráfica Por Un Diseñador Gráfico

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES ACATLÁN CONCEPTUALIZACIÓN DE UN VIDEOJUEGO Y CREACIÓN DE SU INTERFAZ GRÁFICA POR UN DISEÑADOR GRÁFICO TESIS QUE PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN DISEÑO GRÁFICO PRESENTA EDUARDO DANIEL TORRES GÓMEZ ASESOR: LIC. HUGO ADRIÁN ÁBREGO GARCÍA NOVIEMBRE 2012 UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Para mi padre y madre con mucho amor. Agradezco a: Luz María, por mostrarme tanto amor, soportándome. Arturo, Aldo, abuela, tías, tíos, sus hijas e hijitos por ser parte de mi familia, porque sin ellos no sería quien soy. Todos los que hayan dedicado tiempo a mi formación profesional en mayor o menor medida y a los que dedicaron su valioso tiempo en la conformación de este trabajo. ÍNDICE ÍNDICE CAPÍTULO 4: Wii y High Concept Document INTRODUCCIÓN.......................................................................................1 4. Antecedentes de Wii............................................................................63 4.1. Especifi caciones técnicas.................................................................64 CAPÍTULO 1: Videojuegos, ¿qué son? 4.1.2. Wii remote.....................................................................................65 1. El juego y sus funciones........................................................................5 4.2. -

How the Wii Came to Be

Chapter 1 How the Wii Came to Be In This Chapter Reliving the Wii’s secretive development Finding a system in stores f you’re like a lot of new Wii owners, you probably don’t know much about Iyour new purchase or the story behind it. Sure, you may have heard a snippet on the local news about how the system was almost impossible to find after its initial release in late 2006. You even may have read a newspaper story about how the system is catching on with all sorts of unlikely groups of new gamers. These factoids are just a part of the story behind the Wii. This chapter covers the hundred-plus year history of Nintendo leading up to the launch of the Wii and beyond. Nintendo’s early years Nintendo wasn’t always the electronic-enter- simple, one-room office that had once served tainment powerhouse it is today. The company as its headquarters. was originally founded in 1889 as a producer of By the 1950s, control of Nintendo had trans- traditional handmade Japanese playing cards ferred to Hiroshi Yamauchi, Fusajiro’s grandson. called hanafuda. The name “Nintendo” roughly He expanded the company’s card business by translates to “Leave COPYRIGHTEDluck to heaven.” Company MATERIAL introducing plastic-coated cards in 1953 and, in founder Fusajiro Yamauchi had plenty of luck 1959, signed on with Walt Disney Co. to sell cards when the Yakuza (the Japanese mafia) took a printed with popular Disney characters. The new liking to Nintendo’s cards for their illegal gam- Disney-branded cards took the Japanese play- bling halls. -

Voglia Di Vincere: Trucchi Facili!

Guide e consigli Nintendo Wii Voglia di vincere: trucchi facili! La saletta musicale Sbloccare i vari scenari nei quali suonare e reinterpretare i brani di Wii SCOPRITE COME OTTENERE IL MASSIMO DA Wii Music! Music non è affatto difficile, visto che basta seguire le prime lezioni di Sebastian Domisol, quelle di base e avanzate del genere rock e affrontare la sfide del direttore d’orchestra e del concerto di campanelle. Questa sera per suonare mi vesto così! Ottenere l’ultimo scenario, la saletta musicale, è invece un po’ più difficile perché bisogna superare tutti e otto i livelli della modalità Indovina la Nota. Abbiamo pensato di proporvi le soluzioni degli esercizi finali, che sono i più impegnativi in assoluto. Disponete i Mii Sapevate che potete decidere quale vestito indossare per le vostre esibizioni? seguendo i seguenti schemi e non dovreste avere problemi di sorta! Forse no, perché questa è un’opzione segreta e molto ben nascosta. Se volete saperne di più, continuate a leggere! Livello 3 1 Dopo aver scelto la modalità di gioco Esibizione vi troverete davanti a questa Livello 1 schermata. Scegliete quale Mii Livello e quale strumento usare e poi 2 premete il tasto A sull’icona OK. Livello 3 + 4 2 A questo punto comparirà questa schermata. Qui, quando darete l’ok con il tasto A dopo aver portato Tutti i Mii in maglietta Livello 5 il puntatore sull’icona Inizia, tenete premuti i seguenti a maniche corte! tasti per vestirvi in maniera assai stravagante! + + + Livello 6 Tutti i Mii saranno Tutti i Mii saranno vestiti da DJ! travestiti da cane! Livello 7a + + + Livello 8a Tutti i Mii avranno Tutti i Mii saranno la divisa da karateka! travestiti da gatto! COME SBLOCCARE IL TEMA DI SUPER MARIO BROS! + + + Livello 8b Tutti i Mii saranno vestiti Tra i tanti brani di Tutti i Mii saranno Wii Music , trova da ragazze pon pon! Livello 7b spazio anche il famosissimo tema vestiti con il frac. -

You, Me and the Wii: Nintendo Wii's in School Libraries

You, Me and the Wii: Nintendo Wii’s in School Libraries Why Gaming in the School Library? • Digital Game Based Learning meets the needs and learning styles of today’s and the future’s generation of learners. • Digital Game Based Learning is motivating because it is fun. • Digital Game Based Learning is enormously versatile, adaptable to almost any subject, information, or skill to be learned, and when used correctly, is extremely effective. -Marc Prensky, Digital Game Based Learning, ©2001 Nintendo Wii in School Libraries: The Nintendo Wii strategically placed in a school library setting has the unique ability to promote collaborative units of study with teachers in multiple content areas. This investment creates the architecture for digital game based learning that can (1) connect to classroom instruction and New York State standards and benchmarks for learning, (2) motivate students to learn content, (3) provide opportunities to learn and practice critical 21st century information literacy skills, and (4) allow for aesthetic growth and provide a fun and effective way for students to learn. In Connection with the American Association of School Libraries Standards for the 21st Century Learner: • Students actively participate in the gaming experience and work with information to make inferences and create meaning. • Games are engaging and often have a learning curve that builds toward proficiency. Students have the potential to excel within a game by self-monitoring how they utilize information during play to determine its usefulness and effectiveness. • Games are participatory and encourage learning communities through sharing of concepts and strategies, collaboration amongst players and reflection on personal performance.