Classics in Indian Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Patron-In-Chief Honorary Fellows Founder Fellows

Patron-in-Chief 1. Dr. Rajendra Prasad 2. Dr. S. Radhakrishnan 3. Dr. Zakir Husain 4. Shri V.V. Giri 5. Shri Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed 6. Shri Giani Zail Singh Honorary Fellows 1. Shri Jawahar Lal Nehru 2. Dr. B.C. Roy 3. Major Genl. S.L. Bhatia 4. Col. R.N. Chopra 5. Dr. H.M. Lazarus 6. Dr. Jivaraj N. Mehta 7. Dr. A. Lakshamanswami Mudaliar 8. Dr. N.A. Purandare 9. Major Genl. S.S. Sokey 10. Dr. A.C. Ukil 11. Dr. Sushila Nayar 12. Smt. Indira Gandhi 13. Dr. V.T.H. Gunaratne 14. Dr. Dharmendra 15. Shri P.V. Narasimha Rao Founder Fellows 1. Dr. Madan Lal Aggarwal 2. Dr. B.K. Aikat 3. Dr. S.T. Achar 4. Dr. (Col.) Amir Chand 5. Dr. A.A. Ayer 6. Dr. Santokh Singh Anand 7. Dr. R.B. Arora 8. Dr. L.H. Athle 9. Dr. A.V. Baliga 10. Dr. Baldev Singh 11. Dr. Bankat Chandra 12. Dr. A.K. Basu 13. Dr. B.B. Bhatia 14. Dr. T.N. Banerjee 15. Dr. Bimal Chandra Bose 16. Dr. J.C. Banerjee 17. Dr. E.J. Borges 18. Dr. P.V. Cherian 19. Dr. R.N. Chaudhuri 20. Dr. G. Coelho 21. Dr. R.A.F. Cooper 22. Dr. (Lt.Genl.) D.N. Chakravarti 23. Dr. L.W. Chacko 24. Dr. M.K.K. Menon 25. Dr. Subodh Mitra 26. Dr. (Capt) P.B. Mukherjee 27. Dr. S.R. Mukherjee 28. Dr. B. Mukhopadhaya 29. Dr. M. Naidu 30. Dr. B. Narayana 31. Dr. C.G. -

Indian Council of Medical Research New Delhi © 2005 Indian Council of Medical Research

Annual Report 2003-2004 Indian Council of Medical Research New Delhi © 2005 Indian Council of Medical Research Prof. N.K. Ganguly: Director-General Dr. K. Satyanarayana: Chief (Publication & Information) Complied and Edited by Dr. Sudha Chauhan, DDG (SG) Published by the Division of Publication, Information and Communication on behalf of the Director-General, Indian Council of Medical Research New Delhi 110029 Layout Design & Production Control by ICMR Press Unit Printed at: S. Narayan & Sons, B-88, Okhla Indl. Area, Phase-II, New Delhi Tel: 26385873 he Indian Council of Medical Research has made significant strides in its mandate of ‘Research for TBetter Health’. The Council has lived up to country’s expectations on all major fronts of its activity: research and development of vaccines and drugs for infectious diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, filariasis, HIV/AIDS, research in the areas of modern biology like molecular biology, genomics, bioinformatics, fertility regulation, cancer and other non-communicable diseases, consultancy and human resource development, national and international collaborations and biomedical informatics and communication. During the period under report, the Memorandum for the Expenditure Finance Committee (EFC) of ICMR has been approved by the Government of India and Rs.870 Crores have been allocated for the 10th Plan. The research activities will now be pursued with greater vigour as more funding would be available. To optimize resource utilization, the Council is using the Combined Approach Matrix being used by Global Health Forum for Health Research for setting research priorities in various disciplines. The Council continued to play an important role in detecting new and emerging infections in India like the Chandipura virus encephalitis in Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat and outbreak of mysterious fever in Siliguri. -

Signatory ID

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02050005 NARAYANA PARASU RAMAN U74140DL2008PTC176162 AAGS-PRADGA BIOTECH PRIVATE 02050011 DHIRUKUMAR PATEL U32109GJ2006PTC048621 TRUE SOLUSALES PRIVATE LIMITED 02050012 BHANDARI SHANTICHAND U51909MH2004PTC144101 BESTLINE MERCANTILE COMPANY 02050012 BHANDARI SHANTICHAND U45200MH2008PTC179711 WOODSIDE CONSTURCTIONS 02050023 BUCH ROHITKUMAR UTTAMLAL U51395GJ1999PLC036886 EFFLUENT CHANNEL PROJECT 02050028 RASTE SHANTANU SHARAD U24230MH2008PTC180694 PANCHAMVED PHARMA LAB 02050036 JOTHIMANI SUNDARAM U51909TZ2005PTC012404 FLUX EXPORTS (INDIA) PRIVATE 02050045 JAIN PRADEEP U67120MP2008PTC021247 MAGI FINSTOCK PRIVATE LIMITED 02050047 BHALODE RAJENDRA VASANT U85100MH2007PTC169519 KAMAL HEALTH CARE SERVICES 02050047 BHALODE RAJENDRA VASANT U01407MH2008PTC187593 KAMAL KRUSHI AGRO PRIVATE 02050049 PATEL RASIKBHAI RUCHIT U15209GJ2008PTC053135 KRUSHNA CREAM PROCESS 02050051 DEEPAK JAIN U45400DL2008PTC183140 SHRI PARSV PADMAVATI 02050051 DEEPAK JAIN U45400DL2008PTC183138 MANGLIK INFRASTRUCTURES 02050062 GARG KUMAR SANDEEP U70109PB2008PTC031772 SHIV SHANKAR INFRATECH 02050066 BHANDARI HEMANT U67120MP2008PTC021247 MAGI FINSTOCK PRIVATE LIMITED 02050067 ANBARASU SENNIAPPAN U74140TZ2005PTC012225 ACTIVE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS 02050075 PALKAR SONIA VIVEK U24110MH1972PTC016169 NIVEDITA CHEMICALS PRIVATE 02050075 PALKAR SONIA VIVEK U73100MH1979PTC021320 ANEK PRAYOG PRIVATE LIMITED 02050079 DHARMENDER YADAV U70101CH1993PLC013932 CONSOLIDATED DEALERS LIMITED 02050081 BHALODE RAJENDRA SAROJ U85100MH2007PTC169519 KAMAL HEALTH CARE -

An-Re-Patel Chest-2015-16 Annual Report.Pmd

New ward was inaugurated by The Chairman, Governing Body, VPCI on September 22, 2015 A Training Workshop for Ventilation Management of Influenza was held on November 23, 2015. Prof. S.N. Gaur, Director of the Institute with Officer-in-Charge of ICUs of State Medical Colleges. ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute University of Delhi, Delhi, India Published by Professor S.N. Gaur, Director (Acting), Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute, University of Delhi, Delhi-110 007; Phone: 27402435, 27667102, 27667441, 27667667, 27666182 Compiled and Edited by Publication Division, VPCI Cover Design by Photography Division, VPCI Printed at Bengal Offset Works, 335, Khajoor Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110 005 (Phone: 23610455, 23674614) This Annual Report can be accessed at website: www.vpci.org.in 2 Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute Annual Report 2015-16 From the Director’s Desk It is with great pleasure I am presenting the Annual Report of the Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute (VPCI) for the year 2015-16. The report provides an overview of the wide range of activities and achievements of the Institute in the areas of post-graduate medical education, research and patient-care. Postgraduate medical education is one of the thrust areas of the Institute. Students are trained for DM, MD, DTCD and PhD courses in Pulmonary Medicine, MD and PhD in Biochemistry Physiology, Microbiology and Pharmacology. A large number of physicians, para-medical staff and students from other institutions/ colleges were also trained in various departments of the Institute including summer training. The research contributions from the Institute are widely acclaimed. The vibrancy of these research projects/activities can be well judged from the list of publications in peer-reviewed journals, orations, guest lectures delivered and papers presented in the International and National Conferences by the faculty members and students of the Institute. -

Indian Contribution in Medical Science — Modern Medicine (Part 1)

Journal of The West Bengal University of Health Sciences October 2020 Vol 1 Issue 2 EDITORIAL Indian contribution in medical science — Modern medicine (Part 1) Manidip Pal The modern medicine has entered India 1893 & passed Licentiate of the College of with the arrival of European traders (1600 Physicians, Edinburg (LRCP), Licentiate of A.D.) and their colonialisation in India. the College of Surgeons, Glasgow (LRCS), ‘Ecole de Medicine de Pondicherry’ (present & Licentiate of the Faculty of Physicians JIPMER, Puducherry) was established in and Surgeons, Dublin (LFPS). She practiced 1823 by French Government and started the medicine graciously for 37 years till she teaching western medicine in Asia. Medical expired.2 College, Bengal (present Medical College, Anandi Gopalrao Joshi (1865- Kolkata) established in 28th January 1835 1887) was the first Indian woman to be was the first medical college in Asia to teach qualified as a doctor of western medicine. in English. Chronology has been maintained She received her MD in Obstetrics from the according to the birth year of the legends. Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, Pandit Madhusudan Gupta (1800- USA in 1886. However after returning to 1856), an Ayurved Professor, along with India she could not practice medicine as she Professor H.H. Goodeve, performed the first succumbed to death due to tuberculosis.3 dissection of human dead body by an Indian Rai Bahadur Sir Upendranath at the Medical College, Bengal, raising Brahmachari (1873-1946) had crowned above all the prejudice of the society on the the feather of discovery of Urea Stibamine day of 10th January 1836 which had opened which is an essential drug for treatment the door to Indians to study the subjects of of Kala-azar (Visceral Leishmaniasis). -

(1954-2014) Year-Wise List 1954

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2014) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs 3 Shri Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Venkata 4 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 5 Shri Nandlal Bose PV WB Art 6 Dr. Zakir Husain PV AP Public Affairs 7 Shri Bal Gangadhar Kher PV MAH Public Affairs 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh PB WB Science & 14 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta PB DEL Civil Service 15 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service 17 Shri Amarnath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. 21 May 2014 Page 1 of 193 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 18 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & 19 Dr. K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & 20 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmad 21 Shri Josh Malihabadi PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs 23 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. 24 Dr. Arcot Mudaliar PB TN Litt. & Edu. Lakshamanaswami 25 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PB PUN Public Affairs 26 Shri V. Narahari Raooo PB KAR Civil Service 27 Shri Pandyala Rau PB AP Civil Service Satyanarayana 28 Shri Jamini Roy PB WB Art 29 Shri Sukumar Sen PB WB Civil Service 30 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri PB UP Medicine 31 Late Smt. -

DREAMS WITHOUT an EXPIRY DATE DREAMS WITHOUT an EXPIRY DATE Musings of a People’S Science Activist

DREAMS WITHOUT AN EXPIRY DATE DREAMS WITHOUT AN EXPIRY DATE Musings of a People’s Science Activist MP Parameswaran OUR GLOBAL U 83 Fui Sha Wai Yuen Long, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] Website: www.our-global-u.org First published by OUR GLOBAL U 2016 Copyright © MP Parameswaran All rights reserved 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN-13: 978-988-77616-0-0 The initiative of OUR GLOBAL U supports the proliferation of autonomous and self-managing local bodies and their interdependent networking for ecological and socio-economic sustainability. Our Global U constitutes itself as an experimental forum for alternative practices in the production, dissemination and use of knowledge, making possible different modes of relating to one another and to nature other than what is confined by prevailing dominating institutions and practices. Our Global U seeks to transcend the commodification of knowledge driven by capitalist mechanisms that shape possessive individualistic selves, and hopes to bring together old and new generations of committed people working for ecological justice and socio-economic justice to articulate knowledge produced by experiences in the field, common reflections, and in particular, the wisdoms of elders, women, and communities that defend their commons and rights. Our Global U hopes to help cross-fertilize initiatives practiced by organizations and networks to foster further inter-connections, experiment with creative and equitable forms of interacting, networking, and managing the commons. Our Global U envisions a new sustainable humanity on earth. Contents Abbreviations vii Foreword xiii Introduction xix 1. Early Days 1 Turning the Clock Back 1 School Days 13 From Spinning Wheel to Tricolour Flag 18 2. -

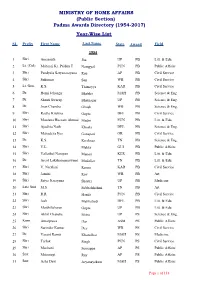

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List SL Prefix First Name Last Name State Award Field 1954 1 Shri Amarnath Jha UP PB Litt. & Edu. 2 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PUN PB Public Affairs 3 Shri Pandyala Satyanarayana Rau AP PB Civil Service 4 Shri Sukumar Sen WB PB Civil Service 5 Lt. Gen. K.S. Thimayya KAR PB Civil Service 6 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha MAH PB Science & Eng. 7 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar UP PB Science & Eng. 8 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh WB PB Science & Eng. 9 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta DEL PB Civil Service 10 Shri Moulana Hussain Ahmad Madni PUN PB Litt. & Edu. 11 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla DEL PB Science & Eng. 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati OR PB Civil Service 13 Dr. K.S. Krishnan TN PB Science & Eng. 14 Shri V.L. Mehta GUJ PB Public Affairs 15 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon KER PB Litt. & Edu. 16 Dr. Arcot Lakshamanaswami Mudaliar TN PB Litt. & Edu. 17 Shri V. Narahari Raooo KAR PB Civil Service 18 Shri Jamini Roy WB PB Art 19 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri UP PB Medicine 20 Late Smt. M.S. Subbalakshmi TN PB Art 21 Shri R.R. Handa PUN PB Civil Service 22 Shri Josh Malihabadi DEL PB Litt. & Edu. 23 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta UP PB Litt. & Edu. 24 Shri Akhil Chandra Mitra UP PS Science & Eng. 25 Kum. Amalprava Das ASM PS Public Affairs 26 Shri Surinder Kumar Dey WB PS Civil Service 27 Dr. Vasant Ramji Khanolkar MAH PS Medicine 28 Shri Tarlok Singh PUN PS Civil Service 29 Shri Machani Somappa AP PS Public Affairs 30 Smt. -

An-Re-Patel Chest-14-15.Pmd

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute University of Delhi, Delhi, India Published and printed by Professoe S.N. Gaur, Director (Acting), Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute, University of Delhi, Delhi-110 007; Phone: 27402435, 27667102, 27667441, 27667667, 27666182, and printed at Bengal Offset Works, 335, Khajoor Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110005 (Phone: 23610455, 23674614). 2 From the Director’s Desk I feel privileged to bring out the Annual Report of the Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute (VPCI) for the year 2014-15. The Report presents as a comprehensive treatise highlighting the present achievements of the Institute in the fields of ‘Education’, ‘Research’, ‘Patient care’ and other developmental activities. The Institute organized the 16th Prof. Raman Viswanathan-VPCI Oration on the occasion of 65th Foundation Day on 6th April 2014. The Oration was delivered by Prof. P.S. Shankar, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka. The Institute also organized the 10th Prof. Autar Singh Paintal Memorial Oration on 24th September 2014. The Oration was delivered by Prof. M. Fahim, former Professor & Head, Dept. of Physiology, VPCI and Adjunct Research Professor, Dept. of Physiology, Hamdard Institute of Medical Sciences & Research, JamiaHamdard, New Delhi. During the year, the Institute initiated an Oration in honour of our former Director, Prof. H.S. Randhawa, an internationally acclaimed Medical Mycologist. The 1st Prof. H.S. Randhawa Oration was delivered by Prof. Ziauddin Khan, Chairman, Dept. of Microbiology, Kuwait University, Kuwait, on 12th January 2015. Fulfilling one of the mandates of the Institute, many scientific programmes were organised during this year. -

Year Book 2021

L SCIE NA NC IO E Y T A A C N A N D A E I M D Y N E I A R YYearear BBookook B ooff O TThehe IIndianndian NNationalational O SSciencecience AAcademycademy K 22021021 22021021 Angkor, Mob: 9910161199 Angkor, Fellows 2020 i The Year Book 2021 Volume–I S NAL CIEN IO CE T A A C N A N D A E I M D Y N I INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY New Delhi ii The Year Book 2021 © INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY ISSN 0073-6619 E-mail : esoffi [email protected], [email protected] Fax : +91-11-23231095, 23235648 EPABX : +91-11-23221931-23221950 (20 lines) Website : www.insaindia.res.in; www.insa.nic.in (for INSA Journals online) INSA Fellows App: Downloadable from Google Play store Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) Dr. Amit Ghosh, FNA Production Dr Sudhanshu Aggarwal Shruti Sethi Published by Dr Amit Ghosh, Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) on behalf of Indian National Science Academy, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi 110002 and printed at Angkor Publishers (P) Ltd., B-66, Sector 6, NOIDA-201301; Tel: 0120-4112238 (O); 9910161199, 9871456571 (M) Fellows 2020 iii CONTENTS Volume–I Page INTRODUCTION ....... v OBJECTIVES ....... vi CALENDAR ....... vii COUNCIL ....... ix PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xi RECENT PAST VICE-PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xiii SECRETARIAT ....... xiv THE FELLOWSHIP Fellows – 2021 ....... 1 Foreign Fellows – 2021 ....... 151 Pravasi Fellows – 2021 ....... 168 Fellows Elected – 2020 (effective 1.1.2021) ....... 169 Foreign Fellows Elected – 2020 (effective 1.1.2021) ....... 177 Fellowship – Sectional Committeewise ....... 178 Local Chapters and Conveners ...... -

Year Book of the Indian National Science Academy

NAL SCIEN IO CE T A A C N A N D A E I M D Y N I Year Book of The Indian National Science Academy 2020 Volume II Fellows i The Year Book 2020 Volume–II AL SCIEN ON C TI E A A N C A N D A E I M D Y N I INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY New Delhi ii The Year Book 2020 © INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY ISSN 0073-6619 E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] Fax : +91-11-23231095, 23235648 EPABX : +91-11-23221931-23221950 (20 lines) Website : www.insaindia.res.in; www.insa.nic.in (for INSA Journals online) INSA Fellows App: Downloadable from Google Play store Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) Professor Gadadhar Misra, FNA Production Dr Sudhanshu Aggarwal Shruti Sethi Published by Professor Gadadhar Misra, Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) on behalf of Indian National Science Academy, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi 110002 and printed at Angkor Publishers (P) Ltd., B-66, Sector 6, NOIDA-201301; Tel: 0120-4112238 (O); 9910161199, 9871456571 (M) Fellows iii CONTENTS Volume-II Page INTRODUCTION ....... v OBJECTIVES ....... vi CALENDAR ....... vii COUNCIL ....... ix PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xi RECENT PAST VICE-PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xii SECRETARIAT ....... xiii FELLOWS & FOREIGN FELLOWS DECEASED DURING THE YEAR 2019 ....... 1 NUMBER OF FELLOWS, FOREIGN FELLOWS & PRAVASI FELLOWS ....... 1 FELLOWS & FOREIGN FELLOWS DECEASED SINCE THE ....... 2 FOUNDING OF THE ACADEMY INSA REPRESENTATION ON OTHER ORGANISATIONS ....... 11 RULES OF INSA ....... 12 REGULATIONS ....... 27 ACADEMY AWARDS ....... 36 International Awards ....... 36 General Medals & Lectures ....... 37 Subjectwise Medals/Lectures/Awards ......