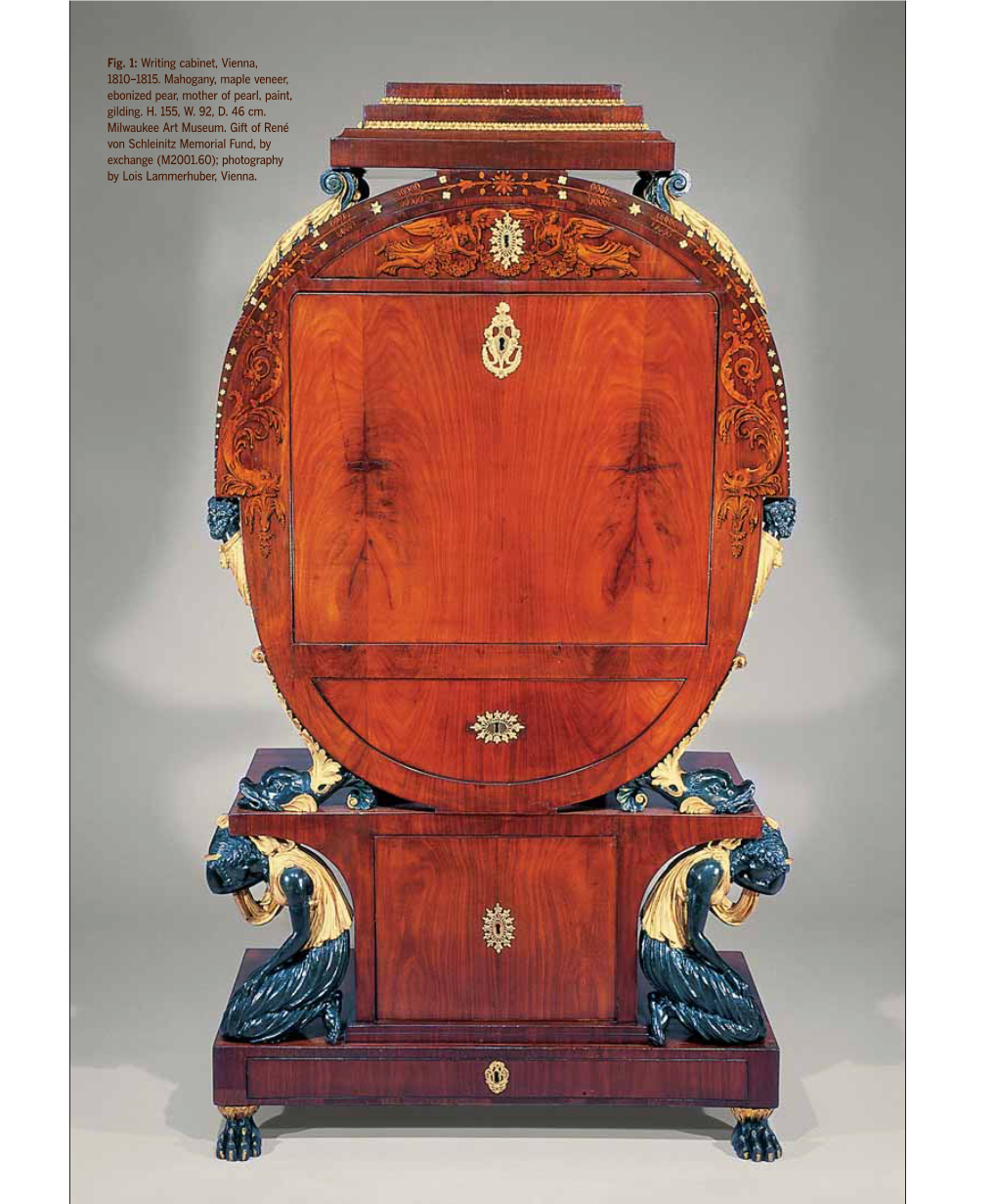

Fig. 1: Writing Cabinet, Vienna, 1810–1815

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI Bell & Howell Information and beaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Aibor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 CRITICAL DISCOURSE OF POSTMODERN AESTHETICS IN CONTEMPORARY FURNITURE: AN EXAMINATION ON ART AND EVERYDAY LIFE IN ART EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sun-Ok Moon ***** The Ohio State University 1999 Dissertation Committee: ^Approved by Dr. -

The Furnishing of the Neues Schlob Pappenheim

The Furnishing of the Neues SchloB Pappenheim By Julie Grafin von und zu Egloffstein [Master of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow] Christie’s Education London Master’s Programme October 2001 © Julie Grafin v. u. zu Egloffstein ProQuest Number: 13818852 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818852 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 l a s g o w \ £5 OG Abstract The Neues SchloB in Pappenheim commissioned by Carl Theodor Pappenheim is probably one of the finest examples of neo-classical interior design in Germany retaining a large amount of original furniture. Through his commissions he did not only build a house and furnish it, but also erected a monument of the history of his family. By comparing parts of the furnishing of the Neues SchloB with contemporary objects which are partly in the house it is evident that the majority of these are influenced by the Empire style. Although this era is known under the name Biedermeier, its source of style and decoration is clearly Empire. -

Roy Lichtenstein's Drawings. New York, Museum of Modern

EXHIBITION REVIEWS and located anything that looks Biedermeier in a bourgeois milieu. The traditional view has recently come under damaging scrutiny. Dr Haidrun Zinnkann in a study of furniture produced in Mainz - an important centre of manu- facture - has looked at cabinet-makers' order books, finding that it was the aris- tocracy who first commissioned pieces in Biedermeier style. Only around 1830 did the local Mainz middle classes, copying their 'social betters', approach manufac- turers for such furniture.2 What of Biedermeier in Munich? Here, the Stadtmuseum collection is important because so many of its 300-odd Biedermeier pieces can be dated, and their history documented. To be more precise, the mu- seum has fallen heir to a good deal of furniture from the residences of the former ruling house ofWittelsbach. Between 1806 and 1815 the Wittelsbachs commissioned large numbers of pieces in a style that can only be described as Biedermeier (Fig.76). This furniture was for everyday use, while grander rooms were decorated in Empire style. Thus in Munich Biedermeier appears a full decade before 'it should'. It was in- troduced by a court that also had a taste for French furnishings, and the work was not executed by craftsmen in the town 76. Biedermeierchair, but by the royal cabinet-maker, Daniel, c. 1806-15. and his sub-contractor. (The evidence Height92/46 cm, breadth46.5/44.5 cm. presented to support this is so overwhelm- as to be (Exh. Stadtmuseum, ing incontestable.) Moreover, Munich). enough is known about Munich in this period to be able to say how Biedermeier over from spilled the ruling house into the travellers reached Munich, but they took 2H. -

GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 by CLAUDIA MAREIKE

ROMANTICISM, ORIENTALISM, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY: GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 By CLAUDIA MAREIKE KATRIN SCHWABE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Claudia Mareike Katrin Schwabe 2 To my beloved parents Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisory committee chair, Dr. Barbara Mennel, who supported this project with great encouragement, enthusiasm, guidance, solidarity, and outstanding academic scholarship. I am particularly grateful for her dedication and tireless efforts in editing my chapters during the various phases of this dissertation. I could not have asked for a better, more genuine mentor. I also want to express my gratitude to the other committee members, Dr. Will Hasty, Dr. Franz Futterknecht, and Dr. John Cech, for their thoughtful comments and suggestions, invaluable feedback, and for offering me new perspectives. Furthermore, I would like to acknowledge the abundant support and inspiration of my friends and colleagues Anna Rutz, Tim Fangmeyer, and Dr. Keith Bullivant. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my family, particularly my parents, Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe, as well as to my brother Marius and his wife Marina Schwabe. Many thanks also to my dear friends for all their love and their emotional support throughout the years: Silke Noll, Alice Mantey, Lea Hüllen, and Tina Dolge. In addition, Paul and Deborah Watford deserve special mentioning who so graciously and welcomingly invited me into their home and family. Final thanks go to Stephen Geist and his parents who believed in me from the very start. -

Carl Spitzweg and the Biedermeier

UNIVERSITY OF PUGET SOUND “A CHRONIC TUBERCULOSIS:” CARL SPITZWEG AND THE BIEDERMEIER BENJAMIN BLOCK ART494 PROF. LINDA WILLIAMS March 13, 2014 1 Image List Fig. 1: Carl Spitzweg, English Tourists in Campagna (English Tourists Looking at Ruins). Oil on paper. 19.7 x 15.7 inches, c. 1845. Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen Preussicher Kulturbesitz, Berlin. 2 The Biedermeier period, which is formally framed between 1815 and 1848,1 remains one of the murkiest and least studied periods of European art. Nowhere is this more evident than in the volumes that comprise the contemporary English-language scholarship on the period. Georg Himmelheber, in the exhibition catalogue for Kunst des Biedermeier, his 1987 exhibition at the Münchner Stadtmuseum, states that the Biedermeier style was “a new variety of neo- classicism.”2 William Vaughan, on the other hand, in his work German Romantic Painting, inconsistently places Biedermeier painters in a “fluctuating space” between Romanticism and Biedermeier that occasionally includes elements of Realism as well.3 It is unusual to find such large discrepancies on such a fundamental point for any period in modern art historical scholarship, and the wide range of conclusions that have been drawn about the period and the art produced within indicate a widespread misunderstanding of Biedermeier art by scholars. While there have been recent works that point to a fuller understanding of the Biedermeier period, namely the exhibition catalogue for the 2001 exhibit Biedermeier: Art and Culture in Central Europe, 1815-1848 and Albert Boime’s Art in the Age of Civil Struggle, most broadly aimed survey texts still perpetuate an inaccurate view of the period, and some omit it altogether. -

Ruth Adler Schnee 2015 Kresge Eminent Artist the Kresge Eminent Artist Award

Ruth Adler Schnee 2015 Kresge Eminent Artist The Kresge Eminent Artist Award honors an exceptional artist in the visual, performing or literary arts for lifelong professional achievements and contributions to metropolitan Detroit’s cultural community. Ruth Adler Schnee is the 2015 Left: Keys, 1949. (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London); right: drawing, Glyphs, 1947. Kresge Eminent Artist. This (Courtesy Cranbrook Archives, The Edward and Ruth Adler Schnee Papers.) monograph commemorates her Shown on cover background: Fancy Free, 1949. (Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh and Tim Thayer, life and work. courtesy Cranbrook Art Museum); top left: Woodleaves, 1998; top right: Narrow Gauge, 1957; top center: Bells, 1995; bottom center: Funhouse, 2000; bottom: Plaid, 2001 reissue. Contents 5 57 Foreword Other Voices: By Rip Rapson Tributes and Reflections President and CEO Nancy E. Villa Bryk The Kresge Foundation Lois Pincus Cohn 6 David DiChiera Artist’s Statement Maxine Frankel Bill Harris Life Gerhardt Knoedel 10 Naomi Long Madgett Destiny Detroit Bill Rauhauser By Ruth Adler Schnee 61 13 Biography Transcendent Vision By Sue Levytsky Kresge Arts In Detroit 21 68 Return to Influence Our Congratulations By Gregory Wittkopp From Michelle Perron 22 Director, Kresge Arts in Detroit Generative Design 69 By Ronit Eisenbach A Note From Richard L. Rogers President Design College for Creative Studies 25 70 Inspiration: Modernism 2014-15 Kresge Arts in By Ruth Adler Schnee Detroit Advisory Council 33 Designs That Sing The Kresge Eminent Artist By R.F. Levine Award and Winners 37 72 The Fabric of Her Life: About The Kresge A Timeline Foundation 45 Shaping Contemporary Board of Trustees Living: Career Highlights Credits Community Acknowledgements 51 Between Two Worlds By Glen Mannisto 54 Once Upon a Time at Adler-Schnee, the Store By Gloria Casella Right: Drawing, Raindrops, 1947. -

IS THAT BIEDERMEIER? Amerling, Waldmüller and More

IS THAT BIEDERMEIER? Amerling, Waldmüller and more Lower Belvedere 21 October 2016 to 12 February 2017 József Borsos Emir from Lebanon (Portrait of Edmund Count Zichy), 1843 Oil on canvas 154 × 119 cm Museum of Fine Arts-Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest IS THAT BIEDERMEIER? Amerling, Waldmüller and more Die The Belvedere’s major autumn exhibition focuses on the development of painting in the years between 1830 and 1860 and provocatively asks: “Is that Biedermeier?” Curated by Sabine Grabner, the show runs from 21 October 2016 to 12 February 2017 at the Lower Belvedere. The exhibition centres around Austrian painting and how art developed in the imperial city of Vienna. It features portraits, landscapes, and genre pictures. Painting first blossomed in the 1830s and this heyday continued well beyond the middle of the century, until the building of the Ringstrasse heralded the advent of Historicism in Austrian art. The show therefore begins in the midst of the historical Biedermeier era and continues beyond this period. Painting’s continuous evolution over these years reveals that art and history influenced each other only to a certain extent. The Revolution of 1848 – marking the end of the Biedermeier period and the era known as Vormärz – is a case in point, as its impact on art was confined to depicting the political event and it had no effect on the technique of painting or the composition of pictures. „The Belvedere is in possession of one of the most outstanding collections of 19th century art, including arthistoric masterpieces. Therefore, it was my wish to look at this era in art history from a new scientific point of view. -

Traditional Floral Styles and Designs

Traditional Styles .................................................................................................................... 2 European Period Designs .................................................................................................................. 2 ITALIAN RENAISSANCE (1400 – 1600) .................................................................................................. 3 DUTCH-FLEMISH (1600s – 1700s) ........................................................................................................ 4 FRENCH BAROQUE: Louis XIV (1661 – 1715) ....................................................................................... 6 FRENCH ROCOCO: Louis XV (1715 – 1774) .......................................................................................... 7 FRENCH NEOCLASSICAL: Louis XVI (1774 – 1793) ................................................................................ 9 FRENCH EMPIRE: Napoleon Bonaparte (1804 – 1814) ...................................................................... 10 BIEDERMEIER (1815 – 1848) .............................................................................................................. 11 English Floral Designs ..................................................................................................................... 13 GEORGIAN (1714 – 1830) .................................................................................................................. 14 VICTORIAN (1830 – 1901) ................................................................................................................. -

Historicism and Decorative Arts Theory in Germany and Austria, 1851-1901

Historicism and Decorative Arts Theory in Germany and Austria, 1851-1901 Eric Anderson Tuesday 6-8 pm Spring 2006 [email protected] In the second half of the nineteenth century, a wide-ranging movement to strengthen national art industries and improve the artistic quality of domestic interiors developed in Germany and Austria. At its heart was the belief that only by grappling with the past could modern designers meet the challenge of creating artistic environments suited to the new demands of a rapidly transforming society. From this conviction arose a rich theoretical discourse on historical forms and their relationship to the present. This course examines the concept of Historicism as it was developed in books, periodicals, and exhibition displays. What narratives of design history did theorists construct? How did they view the role of the decorative arts and the artistic interior in modern society? What were the social and artistic concerns underlying their arguments about the modern use of particular historical styles? General Reference: • Barry Bergdoll, European Architecture, 1750-1890 (Oxford, 2000) [C-H RESERVE / SUGGESTED PURCHASE] • Mitchell Schwarzer, German Architectural Theory and the Search for Modern Identity (New York, 1995) [PHOTOCOPY / PARSONS GIMBEL LIBRARY / NYU BOBST LIBRARY] • John Heskett, Design in Germany, 1870-1918 (London, 1986) [C-H RESERVE] • Stefan Muthesius, Das englische Vorbild: eine Studie zu der deutschen Reformbewegungen in Architektur, Wohnbau und Kunstgewerbe im späteren 19. Jahrhundert (Munich, 1974) [BOBST] • Heinrich Kreisel, Die Kunst des deutschen Möbels, v. 3: Georg Himmelheber, Klassizismus, Historismus, Jugendstil (Munich, 1973) [C-H RESERVE] • David Blackbourn, The Long Nineteenth Century: A History of Germany, 1780-1918. -

Phenomenon of the Biedermeier Piano Music in Xix Century

Science Review ISSN 2544-9346 ART PHENOMENON OF THE BIEDERMEIER PIANO MUSIC IN XIX CENTURY Nataliia Chuprina Ph. D in History of Arts, Acting Associate Professor of the Department of General and specialized piano Odessa National A.V. Nezhdanova Academy DOI: https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_sr/30112019/6814 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received 21 September 2019 The aim of the article – to consider the Biedermeier as a phenomenon of Accepted 15 November 2019 European culture, generated by the Restoration era. The evolutionary and Published 30 November 2019 typological qualities of Biedermeier in all the diversity of its national models (German, Polish, Russian, Italian, French) are projected on the piano music of KEYWORDS XIX century and its performing traditions; to present Biedermeier as a specific direction of musical art which creates the conditions for understanding and Biedermeier, pre-Biedermeier, absorbing of a complex academic repertoire by an unprepared audience. post-Biedermeier, Methodology of the article – historical, general philosophical, social analysis Romanticism, Restoration. of the Biedermeier as a cultural phenomenon, comparative analysis of national characteristics of the Biedermeier display. Scientific novelty – the Biedermeier phenomenon is presented as a specific direction of musical art which creates the conditions for understanding and absorbing of a complex academic repertoire by an unprepared audience. Biedermeier traits characteristic of different national and religious traditions are also analyzed and presented. Conclusions: the Biedermeier as a specific phenomenon of musical culture, a kind of connecting musical “link” between elite art and “mass consumer” of art, creates certain pedagogical prerequisites for raising interest in various social strata of the society for the complex repertoire of classical music. -

86-245 20319 05. Arts And

FPO NO FRAME ArtsCollege and of Letters FPO NO FRAME 88 89 COLLEGE OF ARTS AND LETTERS American Studies Admission Policies. Admission to the College of Arts College of Arts and Letters Anthropology and Letters takes place at the end of the first year. Arabic Studies The student body of the College of Arts and Letters The College of Arts and Letters is the oldest, and Art: thus comprises sophomores, juniors and seniors. traditionally the largest, of the four undergraduate Art History The prerequisite for admission of sophomores colleges of the University of Notre Dame. It houses Design into the College of Arts and Letters is good standing 17 departments and several programs through which Studio at the end of the student’s first year. students at both undergraduate and graduate levels Classics: The student must have completed at least 24 pursue the study of the fine arts, the humanities and Classical Civilization credit hours and must have satisfied all of the the social sciences. Greek specified course requirements of the First Year of Latin Studies Program: University Seminar; Composition; Liberal Education. The College of Arts and Letters East Asian Languages and Literatures: two semester courses in mathematics; two semester provides a contemporary version of a traditional Chinese courses in natural science; one semester course cho- liberal arts educational program. In the college, Japanese sen from history, social science, philosophy, theology, students have the opportunity to understand Economics literature or fine arts; and two semester courses in themselves as heirs of a rich intellectual and spiritual English physical education or in ROTC. -

Carl Spitzweg and the Biedermeier Benjamin Block University of Puget Sound

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Writing Excellence Award Winners Student Research and Creative Works 3-13-2014 A Chronic Tuberculosis: Carl Spitzweg and the Biedermeier Benjamin Block University of Puget Sound Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/writing_awards Recommended Citation Block, Benjamin, "A Chronic Tuberculosis: Carl Spitzweg and the Biedermeier" (2014). Writing Excellence Award Winners. Paper 50. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/writing_awards/50 This Humanities is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Writing Excellence Award Winners by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF PUGET SOUND “A CHRONIC TUBERCULOSIS:” CARL SPITZWEG AND THE BIEDERMEIER BENJAMIN BLOCK ART494 PROF. LINDA WILLIAMS March 13, 2014 1 Image List Fig. 1: Carl Spitzweg, English Tourists in Campagna (English Tourists Looking at Ruins). Oil on paper. 19.7 x 15.7 inches, c. 1845. Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen Preussicher Kulturbesitz, Berlin. 2 The Biedermeier period, which is formally framed between 1815 and 1848,1 remains one of the murkiest and least studied periods of European art. Nowhere is this more evident than in the volumes that comprise the contemporary English-language scholarship on the period. Georg Himmelheber, in the exhibition catalogue for Kunst des Biedermeier, his 1987 exhibition at the Münchner Stadtmuseum, states that