An Anthropological History of Bastar State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha District Gazetteers Nabarangpur

ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR DR. TARADATT, IAS CHIEF EDITOR, GAZETTEERS & DIRECTOR GENERAL, TRAINING COORDINATION GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ii iii PREFACE The Gazetteer is an authoritative document that describes a District in all its hues–the economy, society, political and administrative setup, its history, geography, climate and natural phenomena, biodiversity and natural resource endowments. It highlights key developments over time in all such facets, whilst serving as a placeholder for the timelessness of its unique culture and ethos. It permits viewing a District beyond the prismatic image of a geographical or administrative unit, since the Gazetteer holistically captures its socio-cultural diversity, traditions, and practices, the creative contributions and industriousness of its people and luminaries, and builds on the economic, commercial and social interplay with the rest of the State and the country at large. The document which is a centrepiece of the District, is developed and brought out by the State administration with the cooperation and contributions of all concerned. Its purpose is to generate awareness, public consciousness, spirit of cooperation, pride in contribution to the development of a District, and to serve multifarious interests and address concerns of the people of a District and others in any way concerned. Historically, the ―Imperial Gazetteers‖ were prepared by Colonial administrators for the six Districts of the then Orissa, namely, Angul, Balasore, Cuttack, Koraput, Puri, and Sambalpur. After Independence, the Scheme for compilation of District Gazetteers devolved from the Central Sector to the State Sector in 1957. -

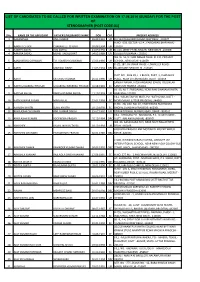

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

Prospects of Religious Tourism in India Dr

Dr. Tulika Sharma Page No. 358 - 367 SHODH SAMAGAM ISSN : 2581-6918 (Online), 2582-1792 (PRINT) Prospects of Religious Tourism in India Dr. Tulika Sharma, Guest Lecturer, SoS in Social Work, Bastar Vishwavidyalaya, Jagdalpur, Dist-Bastar, Chhattisgarh India Abstract :- Religious Tourism is regarded as planning visits to other towns, cities or countries for religious purposes. Religious ORIGINAL ARTICLE tourism is increasing now days. India is widely known for exotic religious places. Religious tourism has been one of the reasons of developing India. Many places like Kedarnath, Mahakaleshwar, Jagannath puri, Tirupati, Gangotri, Yamunotri, Badrinath, Omkareshwar, Kashi Vishwanath, etc are most visited religious places in India. Even Foreigners also come to India to visit these places. The Government is very much aware Corresponding Author : of the importance of religious tourism not only as an economic enabler, but also a tool to make Dr. Tulika Sharma, sure community consensus. Religious tourism Guest Lecturer, is one of the strongest implement to develop SoS in Social Work, Bastar India. Tourism acts as a prominent empower Vishwavidyalaya, Jagdalpur, Dist-Bastar, in facilitating development of basic Chhattisgarh India infrastructural facilities, generates income for the local community as well as the [email protected] government, balances regional development strategies through ‘umbrella’ effect and Received on : 14/11/2019 stimulate tranquility and socio-cultural Revised on : ----- cooperation. But there are some challenges in Accepted on : 20/11/2019 front of government to develop religious Plagiarism : 09% on 15/11/2019 tourism. Some issues or negative impact faced in the development of Religious Tourism in the Country. There some places suffer from the short, but exceptional seasons that change the dynamics of the region for the rest of the year. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

Bastar District Chhattisgarh 2012-13

For official use only Government of India Ministry of Water Resources Central Ground Water Board GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF BASTAR DISTRICT CHHATTISGARH 2012-13 Keshkal Baderajpur Pharasgaon Makri Kondagaon Bakawand Bastar Lohandiguda Tokapal Jagdalpur Bastanar Darbha Regional Director North Central Chhattisgarh Region Reena Apartment, II Floor, NH-43 Pachpedi Naka, Raipur (C.G.) 492001 Ph No. 0771-2413903, 2413689 Email- [email protected] GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF BASTAR DISTRICT DISTRICT AT A GLANCE I Location 1. Location : Located in the SSE part of Chhattisgarh State Latitude : 18°38’04”- 20°11’40” N Longitude : 81°17’35”- 82°14’50” E II General 1. Geographical area : 10577.7 sq.km 2. Villages : 1087 nos 3. Development blocks : 12 nos 4. Population : 1411644 Male : 697359 Female : 714285 5. Average annual rainfall : 1386.77mm 6. Major Physiographic unit : Predominantly Bastar plateau 7. Major Drainage : Indravati , Kotri and Narangi rivers 8. Forest area : 1997.68 sq. km ( Reserved) 390.38 sq. km ( Protected) 2588.75 sq. km (Revenue ) Total – 4976.77 sq.km. III Major Soil 1) Alfisols : Red gravelly, red sandy &red loamy 2) Ultisols : Lateritic,Red & yellow soil IV Principal crops 1) Rice : 2024 ha 2) Wheat : 667ha 3) Maize : 2250 ha V Irrigation 1) Net area sown : 315657 sq. km 2) Net and gross irrigated area : 9592 ha a) By dug wells : 2460 no (758 ha) b By tube wells : 1973 no (2184ha) c) By tank/Ponds : 102 no (1442ha) d) By canals : 15 no ( 421 ha) e) By other sources : 4391 ha VI Monitoring wells (by CGWB) 1) Dug wells -

Constituent Assembly Debates Official Report

Volume VII 4-11-1948 to 8-1-1949 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT REPRINTED BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI SIXTH REPRINT 2014 Printed by JAINCO ART INDIA, New Delhi CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA President : THE HONOURABLE DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD Vice-President : DR. H.C. MOOKHERJEE Constitutional Adviser : SIR B.N. RAU, C.I.E. Secretary : SHRI H.V. IENGAR, C.I.E., I.C.S. Joint Secretary : SHRI S.N. MUKERJEE Deputy Secretary : SHRI JUGAL KISHORE KHANNA Under Secretary : SHRI K.V. PADMANABHAN Marshal : SUBEDAR MAJOR HARBANS RAI JAIDKA CONTENTS ————— Volume VII—4th November 1948 to 8th January 1949 Pages Pages Thursday, 4th November 1948 Thursday, 18th November, 1948— Presentation of Credentials and Taking the Pledge and Signing signing the Register .................. 1 the Register ............................... 453 Taking of the Pledge ...................... 1 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 453—472 Homage to the Father of the Nation ........................................ 1 [Articles 3 and 4 considered] Condolence on the deaths of Friday, 19th November 1948— Quaid-E-Azam Mohammad Ali Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 473—500 Jinnah, Shri D.P. Khaitan and [Articles 28 to 30-A considered] Shri D.S. Gurung ...................... 1 Amendments to Constituent Monday, 22nd November 1948— Assembly Rules 5-A and 5-B .. 2—12 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 501—527 Amendment to the Annexure to the [Articles 30-A, 31 and 31-A Schedule .................................... 12—15 considered] Addition of New Rule 38V ........... 15—17 Tuesday, 23rd November 1948— Programme of Business .................. 17—31 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 529—554 Motion re Draft Constitution ......... 31—47 Appendices— [Articles 32, 33, 34, 34-A, 35, 36, 37 Appendix “A” ............................. -

Royal Asiatic Society

ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN & IRELAND (FOUNDED MARCH, 1823) LIST OF MEMBERS 1959 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY 56 QUEEN ANNE STREET LONDON W. 1 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.126, on 30 Sep 2021 at 11:37:45, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00117630 PRESIDENTS OF THE SOCIETY SINCE ITS FOUNDATION 1823 RT. HON. CHARLES WATKIN WILLIAMS WYNN, M.P. 1841 RT. HON. THE EARL OF MUNSTER. 1842 RT. HON. THE LORD FITZGERALD AND VESEY. 1843 RT. HON. THE EARL OF AUCKLAND. 1849 RT. HON. THE EARL OF ELLESMERE. 1852 RT. HON. THE EARL ASHBURTON. 1855 PROFESSOR HORACE HAYMAN WILSON. 1859 COLONEL WILLIAM HENRY SYKES, M.P. 1861 RT. HON. THE VISCOUNT STRANGFORD. 1864 SIR THOMAS EDWARD COLEBROOKE, BART., M.P. 1867 RT. HON. THE VISCOUNT STRANGFORD. 1869 SIR T. E. COLEBROOKE, BART. 1869 MAJOR-GENERAL SIR HENRY CRESWICKE RAWLINSON, BART. 1871 SIR T. E. COLEBROOKE, BART. 1872 SIR HENRY BARTLE EDWARD FRERE. 1875 SIR T. E. COLEBROOKE, BART. 1878 MAJOR-GENERAL SIR H. C. RAWLINSON, BART. 1881 SIR T. E. COLEBROOKE, BART. 1882 SIR H. B. E. FRERE. 1884 SIR WILLIAM MUIR. 1885 COLONEL SIR HENRY YULE. 1887 SIR THOMAS FRANCIS WADE. 1890 RT. HON. THE EARL OF NORTHBROOK. 1893 RT. HON. THE LORD REAY. 1921 LIEUT.-COL. SIR RICHARD CARNAC TEMPLE. BART. 1922 RT. HON. THE LORD CHALMERS. 1925 SIR EDWARD D. MACLAGAN. 1928 THE MOST HON. THE MARQUESS OF ZETLAND. 1931 SIR E. -

Madhya Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2000 ______Arrangement of Sections ______Part I Preliminary Sections 1

THE MADHYA PRADESH REORGANISATION ACT, 2000 _____________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS _____________ PART I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title. 2. Definitions. PART II REORGANISATION OF THE STATE OF MADHYA PRADESH 3. Formation of Chhattisgarh State. 4. State of Madhya Pradesh and territorial divisions thereof. 5. Amendment of the First Schedule to the Constitution. 6. Saving powers of the State Government. PART III REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURES The Council of States 7. Amendment of the Fourth Schedule to the Constitution. 8. Allocation of sitting members. The House of the People 9. Representation in the House of the People. 10. Delimitation of Parliamentary and Assembly constituencies. 11. Provision as to sitting members. The Legislative Assembly 12. Provisions as to Legislative Assemblies. 13. Allocation of sitting members. 14. Duration of Legislative Assemblies. 15. Speakers and Deputy Speakers. 16. Rules of procedure. Delimitation of constituencies 17. Delimitation of constituencies. 18. Power of the Election Commission to maintain Delimitation Orders up-to-date. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes 19. Amendment of the Scheduled Castes Order. 20. Amendment of the Scheduled Tribes Order. PART IV HIGH COURT 21. High Court of Chhattisgarh. 22. Judges of Chhattisgarh High Court. 23. Jurisdiction of Chhattisgarh High Court. 24. Special provision relating to Bar Council and advocates. 25. Practice and procedure in Chhattisgarh High Court. 26. Custody of seal of Chhattisgarh High Court. 27. Form of writs and other processes. 28. Powers of Judges. 1 SECTIONS 29. Procedure as to appeals to Supreme Court. 30. Transfer of proceedings from Madhya Pradesh High Court to Chhattisgarh High Court. 31. Right to appear or to act in proceedings transferred to Chhattisgarh High Court. -

1941 Census Figures in Present Lay-Out Extimates for 1948

Paper No.2 1949 1941 Census figures in Present lay-out Estimates for 1948 I-AREA, ROUSES :AND POPULATro~ The 1941 oensus fmnres for the Indian Union have beEln a.rranged aooordi.p.g to thtl tlresent* Proyincl!,l, State UJ;1jon fP;'C., lay-out. The present1i<Unpositioii.:'of Provin~es, State Unions etQ, which have qQdargone change due to partit\on- or iht~gration of states is ~en in th~.A ppendix. The table also gives an estimate of the population for 1948 based mainly on the birth/dea.th records. Where there are. IlP:birth/deat}l records tA,e average-for the Pro"\dnoes or the,l'ate for tll~ _adjoirijng Provinoes, h!lo9 been a.d6pt4ld It" do~s vot prbfess to tUltimate speCifica.lly the l')-6pula.tion 'A1Lifts as the "ftlsult of t~47 movdlnents but offers a. dimensional 'piature which< may be of use. Figures given in ~hQU8ands ar~ rounded.Jlldividuall~ f8 the nearest ~and; ~lloe the differenc6.in. iOfn6 cases '861l'\vetm th~ timai1s a.na tne tota! 2. Th(\ a.bsenoe of t(lhail detail!! {ol the pa.fHtioned regi<ms mab,a.it impossible ~ Mhlplete columna 6 ana "'7 in ~egard to 1lqnj ab a.xW Bengal and the ProyJ'O-oes R,nd Union tota.ls 2 I-AREA, HOUSES OOCUPIED Ho USES r---- Ar£a TowDB Villages PERSONS (In thousands) ,-_~ ___.A.. ______ .. Pl'o'rinces, State &c. in sq. miles. r-------A.-------.. Tots.} In ToWlll' In Villages Total Urban Rural 2 3 5 6 7 8 9 10 INDIAN UNION 1,220,011 2,429 560,020 63,815 318,898 44,144 274,754· PROVINCES 709,129 1,585 404,934 241,165 32,139 209,026 Madras 127,768 420 35,932 9,739 1,483 8,256 49,841 7,961 41,879 Bombay. -

From the Editor's Desk

VOLUME-1 l ISSUE-1 l OCTOBER 2020 SAMVAADSHAALAA NEWSLETTER SAMVAADSHAALAA NEWSLETTER From the Editor’s Desk Prof (Dr) Shalini Verma ‘LIFOHOLIC’ Inaugural amaskaar Friends Issue It is an occasion of pride and honour Nfor us to come up with this INA- GUARAL issue of SAMVAADSHAALAA on the auspicious occasion of Shardiya NA- Publisher’s Note VARATRI 2020. The year 2020, as we have seen so far, is an BEFRIEND BOOKS FOR LIFE AND uncommon year – if more for not-so-good NEVER BE ALONE reasons, also for at least a few good ones. Walter Winchell says: Talking of GOOD things this year, it is “A real friend is one who walks in when worth mentioning here that Humans have be- Development Officer Hemanth Kumar Yadav the rest of the world walks out.” come more HUMANE. helped around 800 villagers in Uttar Pradesh Books EMBRACE • When an Air India Express flight carry- get employment under the Kalyani river res- you when you are ALONE ing 190 people from Dubai skidded off the toration project. runway of Kerala’s Kozhikode airport and • RuKart Technologies, a Thane-based agri- Books SOOTHE you when you SUFFER fell into a 35-feet valley, scores of HUMANS tech startup founded by Vikash Jha developed from the neighbouring areas braved the rains Books ILLUMINATE a low-cost innovative machine called the Sub- when you are in ALIENATED and the fear of COVID-19 to reach the site jee Cooler to help marginalised farmers get and helped in the evacuation of the passen- BOOKS33 access to cold storage facilities. -

Volume Xi Orissa

CENOl.T~ 0~~ li~DIA, 1951 VOLUME XI ORISSA PART 1-REP\.R'·' M. AHMED, M.A. · Superintende: 1: oi Censils Operations )rissa CUTTAUJ~ SUPERINTENDENT, OrussA GovF iflmNT PRBSS . 1958 CENSUS OF INDIA, 1951 VOLUME XI ORISSA Part 1-Report . ai't:l~ CENSUS OF INDIA, 1951. VOLUME XI ORISSA PART I-REPORT M. AHMED, M.A. Superintendent of Census Operations Orissa OUT'l'AOX 8lJl'liBIHTBlQ)~. OmasA Go'VBBRJIBJI'I Pus• ~~ TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • .1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE STATE-Geographical Setting-Physical Configuration-Rivers-Cross-Section of Orissa 1-4 II. BRIEF IDSTORY OF THE J,.AND AND THE PEOPLE 4-6 m. dHANGE IN AREA 7 • IV. POPULATION ZONES.. AND NATURAL DIVISIONS 7-9 V. GEOLOGY AND MINERALS-Geological Outline-Mining : Early History Slow Unmethodical Development-Mineral Resources-Orissa Inland. Division -Orissa Coastal Division-Economic Minerals-Iron-Coal-Manganese Bauxite-Chromite-Limestone-Mica-Glasss-and-Vanadium-0 t h. e r Minerals .• 9-15 VI. THE SOIL-Constituents-The Northern Plateau-The Eastern Ghats Region....:.. The Central Tract-The Coastal Division-Soil Erosion 15-17 VII. CLIMATE AND RAINFALL-Orissa Inland Division-Orissa Co.astal Division_:_ Rainfall.Satatistics .. 17-20 VIII. FORESTS-Area-Classification-Districtwise Distribution-Extent-Income and Forest Produce •• 21-23' CHAPTER !-General Population @ SECTION 1-Preliminary .Remarks Population-Comparison with Other States-Reference to Statistics-Non-census Data Inadequate and Erroneous-Indispensability of up-to-date Statistics ·•• 25-27 SECTION 11-General Distribution and Density Comparison with In(lia-Comparison with other States-Comparison with other Countries -Average Density-Thinly Populated Areas-Thickly Populated Areas-Orissa Inland Division-Orissa Coastal Division-Disparity in Density between two Natural Divisions -Increase in Density-Distribution by Districts-Distribution by Police-stations •. -

Prefeasibility Report

Prefeasibility Report For Environment Clearance from MOEF under EIA Notification Dated 14th September, 2006 as Amended Pre - Feasibility Report For Mavliguda Limestone Mine at Village - Mavliguda Tehsil- Bastar & District- Bastar, State- Chhattisgarh. 1. SUMMARY Project - Mavliguda Limestone Mine Name of Company/Mine - Amit Jain Location: Village - Mavliguda Tehsil/Taluka - Bastar District - Bastar State - Chhattisgarh 1. Mining Lease Area & Type of Land - 2.02 / Private Land 2. Geographical Co-ordinates - BOUNDRY POINT LATITUDE LONGITUDE BL1 19°17'47.74"N 81°55'51.18"E BL2 19°17'45.60"N 81°55'55.66"E BL3 19°17'41.51"N 81°55'54.51"E BL4 19°17'43.22"N 81°55'49.93"E BL5 19°17'46.28"N 81°55'50.70"E BL6 19°17'46.44"N 81°55'50.29"E 3. Name of River/ Nallahs /Tanks /Spring - River - 3.70 km (Markandi River at west) / Lakes etc. Nalla - 2.50 km Boria Nalla towards south Tanks - 1.60 km Pond towards north near Sitlawand village area Canal - 6.40 km Canal towards west near Munjla village area Reservoir - 8.00km Reservior towards west near Deoda village area 4. Name of Reserve Forest(s), Wild Life - Boundary of Amadula Reserve Forest passes from 3.50 km Sanctuary/National Park (North) from north boundary of lease area. However NOC from DFO Jagdalpur obtained and enclosed. 5. Topography of the area - Undulated Land devoid of vegitation Altitude - Max. 670 aMSL and Min. 665 aMSL Surface slop - Towards South-East Toposheet No.- 64E/15 6.