Colonialism and Patterns of Ethnic Conflict in Contemporary India By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha District Gazetteers Nabarangpur

ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR DR. TARADATT, IAS CHIEF EDITOR, GAZETTEERS & DIRECTOR GENERAL, TRAINING COORDINATION GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ii iii PREFACE The Gazetteer is an authoritative document that describes a District in all its hues–the economy, society, political and administrative setup, its history, geography, climate and natural phenomena, biodiversity and natural resource endowments. It highlights key developments over time in all such facets, whilst serving as a placeholder for the timelessness of its unique culture and ethos. It permits viewing a District beyond the prismatic image of a geographical or administrative unit, since the Gazetteer holistically captures its socio-cultural diversity, traditions, and practices, the creative contributions and industriousness of its people and luminaries, and builds on the economic, commercial and social interplay with the rest of the State and the country at large. The document which is a centrepiece of the District, is developed and brought out by the State administration with the cooperation and contributions of all concerned. Its purpose is to generate awareness, public consciousness, spirit of cooperation, pride in contribution to the development of a District, and to serve multifarious interests and address concerns of the people of a District and others in any way concerned. Historically, the ―Imperial Gazetteers‖ were prepared by Colonial administrators for the six Districts of the then Orissa, namely, Angul, Balasore, Cuttack, Koraput, Puri, and Sambalpur. After Independence, the Scheme for compilation of District Gazetteers devolved from the Central Sector to the State Sector in 1957. -

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

A Memorable Condolence Meeting in Hyderabad on 27-4-2015

Don't 15Pull thousand Back Podu Adivasi Lands from and Adivasis other tribals’ other tribals 15 thousandDharna Adivasi in Hyderabad and other tribals’Maha on 25-06-2015 Dharna Demand 15 thousand Adivasi and other tribals Participated the Maha Dharna in Hyderabad on 25th May 2015 Since the KCR government came to power, Under the leadership of the party Adivasis the forest official intensified their efforts to throw fought against forest officials started cutting unre- out the Adivasis and other tribals from their Podu served forest and re-occupying their lands. In this lands and occupy their lands forcefully to implant process Podu cultivation also started by the time of teak and other seedlings in those lands. For more emergency. For the last four decades Adivasis have than four and half decades the Adivasis have been been cultivating their podu lands. The adivasis have fighting against the unjust and autocratic methods been demanding Pattas for their lands. Before every of forest officials in the Godavari valley under the elections ruling class parties used to promise for leadership of our party. Forest officials closetted the giving pattas to the Adivasis and other tribes. Soon reserve forest lines into the lands of the Adivasis. after the elections they,in general, forget their They were not allowed to bring firewood and even demands. However, KCR immediately after coming material for broomstick and leaves for taking food to power started anti-Adivasi crusade while prom- etc. Non tribes illegally taken thousands of ising to give 3 acres of land to poor people. Adivasis’ lands giving petty amounts or nothing With the intensification of forest officials and resorting to collect exhorbitant interest rates harassments like fencing the fields of Adivasis, call- from the Adivasis. -

Sr. No. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region

Non-Aided College List Sr. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region Correspondence College No. Address Type 1 Shri. KGM Newaskar Sarvajanik Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Pandit neheru Hindi Non-Aided Trust's K.G. College of Arts & Pune University, ar ar vidalaya campus,Near Commerece, Ahmednagar Pune LIC office,Kings Road Ahmednagrcampus,Near LIC office,Kings 2 Masumiya College of Education Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune wable Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar colony,Mukundnagar,Ah Pune mednagar.414001 3 Janata Arts & Science Collge Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune A/P:- Ruichhattishi ,Tal:- Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar Nagar, Dist;- Pune Ahmednagarpin;-414002 4 Gramin Vikas Shikshan Sanstha,Sant Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune At Post Akolner Tal Non-Aided Dasganu Arts, Commerce and Science Pune University, ar ar Nagar Dist Ahmednagar College,Akolenagar, Ahmednagar Pune 414005 5 Dr.N.J.Paulbudhe Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune shaneshwar nagarvasant Non-Aided Science Women`s College, Pune University, ar ar tekadi savedi Ahmednagar Pune 6 Xavier Institute of Natural Resource Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Behind Market Yard, Non-Aided Management, Ahmednagar Pune University, ar ar Social Centre, Pune Ahmednagar. 7 Shivajirao Kardile Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Jambjamb Non-Aided Science College, Jamb Kaudagav, Pune University, ar ar Ahmednagar-414002 Pune 8 A.J.M.V.P.S., Institute Of Hotel Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag -

Central Committee

COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MAOIST) Central Committee Press Release 10 November 2018 As the General Secretary of CPI (Maoist) Comrade Ganapathy has voluntarily withdrawn from his responsibilities, the Central Committee has elected Comrade Basavaraju as the new General Secretary In view of his growing ill-health and advancing age in the past few years and with the aim of strengthening the Central Committee and with a vision of the future, Comrade Ganapathy voluntarily withdrew from the responsibilities of General Secretary and placed a proposal to elect another comrade as General Secretary in his place, following which the 5th meeting of the Central Committee thoroughly discussed his proposal and after accepting it, elected Comrade Basavaraju (Namballa Kesava Rao) as the new General Secretary. Comrade Ganapathy was elected as the General Secretary of the CPI(ML)(People’s War) in June 1992. That was a very difficult time for the Party. By 1991, the Andhra Pradesh government started the second phase of repression on the Party. The Party was facing several challenges at that time regarding the tactics to be adopted to advance the armed struggle. The then secretary of the Central Committee, Kondapalli Seetharamaiah, was not in a position to overcome those challenges that the Party was facing by leading his committee. In such conditions, instead of overcoming those challenges by basing on all the Party cadres and the people, Kondapalli Seetharamaiah and another member of the Central Committee followed conspiratorial methods and became the cause of internal crisis in the Party. Except a few opportunists, the whole Party stood united in the principled fight against this opportunist clique which made attempts to split the Party. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

GIPE-010149.Pdf

THE PRINCES OF INDIA [By permission of the Jlidor;a f- Albert 1lluseum THE CORONAT I O); OF AN Ii:\DI AN SOVE R E I G:\f From the :\janta Frescoes THE PRINCES OF INDIA WITH A CHAPTER ON NEPAL By SIR \VILLIAM BAR TON K.C.I.E., C.S.I. With an Introduction by VISCOUNT HAL IF AX K.G., G.C.S.l. LONDON NISBET & CO. LTD. 11 BER!'\ERS STllEET, 'W.I TO ~IY '\'!FE JJ!l.il ul Prir.:d i11 Grt~ Eri:Jill liy E11.u::, Wa:.:ctl 6- riney, W., L~ ad A>:esbury Firs! p.,.;::isilll ;,. 1;34 INTRODUCTION ITHOUT of necessity subscribing to everything that this book contains, I W am very glad to accept Sir William Barton's invitation to write a foreword to this con .. tribution to our knowledge of a subject at present occupying so large a share of the political stage. Opinion differs widely upon many of the issues raised, and upon the best way of dealing with them. But there will be no unwillingness in any quarter to admit that in the months to come the future of India will present to the people of this country the most difficult task in practical statesmanship with which thet 1hive ever been confronted. If the decision is to be a wise one it must rest upon a sound conception of the problem itself, and in that problem the place that is to be taken in the new India by the Indian States is an essential factor. Should they join the rest of India in a Federation ? Would they bring strength to a Federal Government, or weakness? Are their interests compatible with adhesion to an All-India v Vl INTRODUCTION Federation? What should be the range of the Federal Government's jurisdiction over them? These are some of the questions upon which keen debate will shortly arise. -

03404349.Pdf

UA MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT STUDY GROUP Jagdish M. Bhagwati Nazli Choucri Wayne A. Cornelius John R. Harris Michael J. Piore Rosemarie S. Rogers Myron Weiner a ........ .................. ..... .......... C/77-5 INTERNAL MIGRATION POLICIES IN AN INDIAN STATE: A CASE STUDY OF THE MULKI RULES IN HYDERABAD AND ANDHRA K.V. Narayana Rao Migration and Development Study Group Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 August 1977 Preface by Myron Weiner This study by Dr. K.V. Narayana Rao, a political scientist and Deputy Director of the National Institute of Community Development in Hyderabad who has specialized in the study of Andhra Pradesh politics, examines one of the earliest and most enduring attempts by a state government in India to influence the patterns of internal migration. The policy of intervention began in 1868 when the traditional ruler of Hyderabad State initiated steps to ensure that local people (or as they are called in Urdu, mulkis) would be given preferences in employment in the administrative services, a policy that continues, in a more complex form, to the present day. A high rate of population growth for the past two decades, a rapid expansion in education, and a low rate of industrial growth have combined to create a major problem of scarce employment opportunities in Andhra Pradesh as in most of India and, indeed, in many countries in the third world. It is not surprising therefore that there should be political pressures for controlling the labor market by those social classes in the urban areas that are best equipped to exercise political power. -

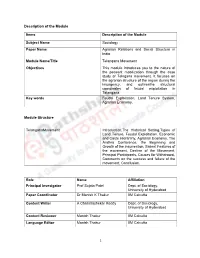

1 Description of the Module Items Description of the Module Subject

Description of the Module Items Description of the Module Subject Name Sociology Paper Name Agrarian Relations and Social Structure in India Module Name/Title Telangana Movement Objectives This module introduces you to the nature of the peasant mobilization through the case study of Telngana movement. It focuses on the agrarian structure of the region during the insurgency, and oulinesthe structural coordinates of feudal exploitation in Telangana. Key words Feudal Exploitation, Land Tenure System, Agrarian Economy. Module Structure TelanganaMovement Introduction,The Historical Setting,Types of Land Tenure, Feudal Exploitation, Economic and Caste Hierarchy, Agrarian Economy, The Andhra Conference, the Beginning and Growth of the insurrection, Salient Features of the movement, Decline of the Movement, Principal Participants, Causes for Withdrawal, Comments on the success and failure of the movement, Conclusion. Role Name Affiliation Principal Invesigator Prof Sujata Patel Dept. of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator Dr Manish K Thakur IIM Calcutta Content Writer A Chandrashekar Reddy Dept. of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Content Reviewer Manish Thakur IIM Calcutta Language Editor Manish Thakur IIM Calcutta 1 Introduction: Social movements have always been an inseparable part of social progress. Through collective action, organizedprotests and resisting the structures of domination,peasant movements have historically paved the way for new thoughts and actions that revitalizes the process of social change (Singha Roy, 2004). TelanganaMovement was one such movement in the 20th century India which had ended the feudalistic oppression of landlords and the autocratic Nizam rule in the Telangana.The Telangana movement of the mid-1940s and the early 1950s was unparalleled in the 20th century history of India for its intensity, participants’ militancy and the height of revolutionism they ascended. -

An D. S A·Na·Ds·

Treaties Engageme~t$. ... • • • ' .. ~ J ~ an d. S a·na·ds· I ,_' • ._ • • II'.·,. "'. A Contribution in · Indian Jurisprudence. r, . £ R. R:SASTRY ' ,CISUSIIED BY TilE .lUTUOa USIVERSilY • .u.L\HAB.U> Treaties, Engagements and .Sanads . .. of .. .• . ~ IN p 1·-A. N ·:s T A·T E'S ~ A CONTRIBunON IN.. , INDIAN JURISPRUDENCE • BJ . .. ' .~ R. R. SASTRY, M.A., !tLL lUDEll. LAW DEPAlln.t:ENT1 VNIVEB.Sm OP .UUIUIJ.D; .ADVOCATE, WADilAI HIGH COUllT; ~ Gl01WI SOCIETr {LONDON) ,,.' ~ • . Author o£ . • , · . , lt~ltf11alional Lt. IIJJ; Inaitlfl Stalrt t~t~l Rl~ptJ•siW, .. CoVfr1111WIIIIJJ1' Ptlr.tllfJIIRiry tlfiJ Slllll SMbju'll, IJili Indiat1 S/(J/111 IJII · · PUBUSH.ED BY THE AU'fHOR Pria .IU.If-1""-J * II u..-F~nibf COPYRIGHT WITH THE AUTHOR , PlliN'I'ED Bl' J• ~ SH4.JUIA AT I'HE ALLAHABAD LAW JOURNAL PRESS . • .. · ALLAHABAD AUTHOR'S PREFACE While continuously engaged in studies o£ scvenl aspects o£ the problems of Indian States for the past sev~n years, it appeared that a tompktt IZMb·tkaltXIJmi· nation D/ tht ltVtral Trealitl, EngogtmtnllllnJ S11fllllll h1d not been done thus far. No '\l·ork h1s been written which subjects these tta.ties, engagements, and Sllfll1111. to a proetss of ana!Jsis and interprw.tion. · · · Certain aspects of the problem oC lnJ.ia11 Sta/11 t•is-a-vis responsible Government in lnda h1ve been attempted in a vmrk of the author published in 1939·* The all~absorbing question of Paramollfllty anJ 'Stalt SII!juts had been chosen by this writer for the Sayaji Rao Gaeb·ar Golden Jubilee Memorial Uct:ures at Baroda in 194~41. -

Political History of Modern Kerala.Pmd

Political History of Modern Kerala Chapter III POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT OF COCHIN Introduction he political movements in Cochin offer almost a contrast to those Tof Travancore in respect of their origin, character and course of events. There is no such phase in the modern history of Cochin as the one marked by the Memorials in the politics of Travancore. The fact that the princes of the large-sized Cochin royal family entered into matrimonial relations with Nair families ensured for the Nair community a privileged position in the civil services and there was no need for them to petition or protest in regard to denial of jobs as in Travancore. The communal overtones associated with the movements in Travancore were also by and large absent in Cochin. Whereas the Government of Travancore proceeded with liberal social reforms like Temple Entry, the Government of Cochin not only followed a policy of caution in this field but even opposed the move for Temple Entry. At the same time, in Travancore the GovernmentBOOKS adopted a policy of opposition to the popular demand for responsible government while in Cochin it implemented a liberal policy of conceding this demand by stages. Mention should also be made in this context of the personal factor. Sir R.K. ShanmukhamDC Chetti who was the Dewan of Cochin in the crucial thirties was much different from Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar, his counterpart in Travancore at the time, in his outlook and approach.This was mainly because the former was a leading light of the non-Brahmin movement in the Madras Presidency before he accepted the office of the Dewan of Cochin. -

Travancore-Cochin Integration; a Model to Native States of India

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Travancore-Cochin Integration; A model to Native states of India Dr Suresh J Assistant Professor, Department Of History University College, Thiruvanathapuram Kerala University Abstract The state of Kerala once remained as an integral part of erstwhile Tamizakaom. Towards the beginning of the modern age this political terrain gradually enrolled as three native kingdoms with clear cut boundaries. The three native states comprised kingdom of Travancore of kingdom of Cochin, kingdom of Calicut These territories never enjoyed a single political structure due to the internal and foreign interventions. Travancore and Cochin were neighboring states enjoyed cordial relations. The integration of both states is a unique event in the history of India as well as History of Kerala. The title of Rajapramukh and the administrative division of Dewaswam is unique aspect in the course of History. Keywords Rajapramukh , Dewaswam , Panjangam, Yogam, annas, oorala, Melkoima Introduction The erstwhile native state of Travancore and Cochin forms political unity of Indian sub- continent through discussions debates and various agreements. The states situating nearby maintained interstate reactions in various realms. At occasionally they maintained cordial relation on the other half hostile in every respect. In different epochs the diplomatic relations of both the state were unique interns of political economic, social and cultural aspects. This uniqueness ultimately enabled both the state to integrate them ultimate into the concept of the formation of the state of Kerala. The division of power in devaswams and assumed the title Rajapramukh is unique chapters in Kerala as well as Indian history Volume XII, Issue VII, 2020 Page No: 128 Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Scope and relevance of Study Travancore and Cochin the native states of southern kerala.