Beyond the Beyond the Barricades. the 1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Vigilantism V. the State: a Case Study of the Rise and Fall of Pagad, 1996–2000

Vigilantism v. the State: A case study of the rise and fall of Pagad, 1996–2000 Keith Gottschalk ISS Paper 99 • February 2005 Price: R10.00 INTRODUCTION South African Local and Long-Distance Taxi Associa- Non-governmental armed organisations tion (SALDTA) and the Letlhabile Taxi Organisation admitted that they are among the rivals who hire hit To contextualise Pagad, it is essential to reflect on the squads to kill commuters and their competitors’ taxi scale of other quasi-military clashes between armed bosses on such a scale that they need to negotiate groups and examine other contemporary vigilante amnesty for their hit squads before they can renounce organisations in South Africa. These phenomena such illegal activities.6 peaked during the1990s as the authority of white su- 7 premacy collapsed, while state transfor- Petrol-bombing minibuses and shooting 8 mation and the construction of new drivers were routine. In Cape Town, kill- democratic authorities and institutions Quasi-military ings started in 1993 when seven drivers 9 took a good decade to be consolidated. were shot. There, the rival taxi associa- clashes tions (Cape Amalgamated Taxi Associa- The first category of such armed group- between tion, Cata, and the Cape Organisation of ings is feuding between clans (‘faction Democratic Taxi Associations, Codeta), fighting’ in settler jargon). This results in armed groups both appointed a ‘top ten’ to negotiate escalating death tolls once the rural com- peaked in the with the bus company, and a ‘bottom ten’ batants illegally buy firearms. For de- as a hit squad. The police were able to cades, feuding in Msinga1 has resulted in 1990s as the secure triple life sentences plus 70 years thousands of displaced persons. -

Grassroots, Vol. 9, No. 1

Grassroots, Vol. 9, No. 1 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org/. Page 1 of 23 Alternative title Grassroots Author/Creator Grassroots Publications (Cape Town) Publisher Grassroots Publications (Cape Town) Date 1988-02 Resource type Journals (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1988 Source Digital Imaging South Africa (DISA) Format extent 8 page(s) (length/size) Page 2 of 23 NON - PROFIT COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERgrassrootsTHE PAPER ABOUT YOU VOL. 9 NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1988 FREEANCCALLSFORUNITYTHE disunite that the apartheid regime generateamongst the oppressed people ensures that it gains alonger lease of life, the African National Congresssaid in a statement from Lusaka earlier this month.Responding to events in KTC, the ANC made aspecial appeal to the militant youth to "take the leadin ensuring that all hostilities amongst our peoplecease at once".The ANC further said: "It is against the colonialapartheid regime that we should direct our anger andaim our blows. -

Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010

Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010 Julian A Jacobs (8805469) University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie Masters Research Essay in partial fulfillment of Masters of Arts Degree in History November 2010 DECLARATION I declare that „Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010‟ is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. …………………………………… Julian Anthony Jacobs i ABSTRACT This is a study of activists from Manenberg, a township on the Cape Flats, Cape Town, South Africa and how they went about bringing change. It seeks to answer the question, how has activism changed in post-apartheid Manenberg as compared to the 1980s? The study analysed the politics of resistance in Manenberg placing it within the over arching mass defiance campaign in Greater Cape Town at the time and comparing the strategies used to mobilize residents in Manenberg in the 1980s to strategies used in the period of the 2000s. The thesis also focused on several key figures in Manenberg with a view to understanding what local conditions inspired them to activism. The use of biographies brought about a synoptic view into activists lives, their living conditions, their experiences of the apartheid regime, their brutal experience of apartheid and their resistance and strength against a system that was prepared to keep people on the outside. This study found that local living conditions motivated activism and became grounds for mobilising residents to make Manenberg a site of resistance. It was easy to mobilise residents on issues around rent increases, lack of resources, infrastructure and proper housing. -

Fr Protest Pathology

VOLUME FIVE NUMBER TWO SUMMER 1988 1 F RL PROTEST PATHOLOGY The Piefermaritzburg Legacy 86) UNIVERSITY OF NATAL. ANC DATA Centre for Applied Social Sciences, Insurge, it Acts 1976-1987 INDABA DILEMMA The Economic F actor CORRUPTION COUPS Bridge Over the River Kei CINDERELLA S HOOLIN Reforming Rural Education BLICAN ENTERPRISES 4 THE D A rTT F» We're as important to the man in the street as we are to the men in Diagonal Street. Being one of the top performers on the stock exchange means a better standard of living for our shareholders, .1 ITU YE oi- But being involved in the country's economic development means the creation 3 A.PS? VttS of more wealth and an improved standard of living for every South African. O.'WMT Wr' It's an involvement that has seen us establish coal mines, stainless steel works, Mi cement, glass and other factories to Hp effectively utilise the country's vast mt resources, to generate more exports, create more jobs, and contribute significantly to the nation's growth. Involvement means responsibility — In education and training, in helping to establish more businesses, and playing a meaningful role in the community — ensuring not only the country's future, but yours too. •k •h >W RAND Mining, cemen ilding supplies, earthmoving equipment, motor vehicles, t food, packaging and textiles •IBMB i NDICATOR SOUTH AFRICA is published four times a year by the Centre for Social and Development Studies at the University of Natal, Durban. Opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the Editorial Committee and should not be taken to represent the policies of companies or organisations sponsoring or advertising in the publication. -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

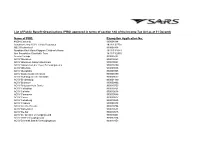

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV -

Cape Town Stadium Durban Stadium Polokwane Stadium Rustenburg Stadium

Cape Town Stadium Durban Stadium Polokwane Stadium Rustenburg Stadium Soccer City Ellis Park Port Elizabeth Stadium Bloemfontein Stadium Nelspruit Stadium Pretoria Stadium 2010 World Cup Calendar Important dates to remember • Media groups arrive 25th April and depart 2 weeks after the Final • FIFA Family arrive around 1st May until 2 weeks after the Final • Teams arrive around 3rd May • Gautrain stations in Sandton and at OR Tambo open 27th May • Supporters arrive around 6th June until departure after post tours • Schools close Wednesday 9th June and re-open Tuesday 13th July 2010 World Cup Stadia Cape Town PtElibthPort Elizabeth Durban Bloemfontein Rustenburg JHB – Ellis Park JHB – Soccer City Pretoria Nelspruit Polokwane = Stadium Locations Hosting cities - matches • Cape Town (8) • 5x15 x 1st round; 1 x 2nd round; 1 x quarter final; 1 x semi-final • Port Elizabeth (8) • 5 x 1st round; 1 x 2nd round; 1 x quarter final; 1 x 3rd place playoff • Durban (7) • 5 x 1st round; 1 x 2nd round; 1 x semi-final • Bloemfontein (6) • 5 x 1st round; 1 x 2nd round • Rustenburg (5) • 4 x 1st round; 1 x 2nd round • JHB – Soccer City and Ellis Park (15) • 10 x 1st round including the Opening; 2 x 2nd round; 2 x quarter final; FINAL Hosting cities - matches continued • Pretoria (()6) • 5 x 1st round; 1 x 2nd round • Nelspruit (5) • 5 x 1st round • Polokwane (4) • 4 x 1st round Fan Parks Polokwane: tbc Newtown: Mary Sandton: Innes- Fitzgerald Square Free Park Nelspruit: Bergvlam Rustenburg: tbc Hoerskool Kliptown: Walter Sisulu Square Soweto: Additional -

The City of Johannesburg Is One of South Africa's Seven Metropolitan Municipalities

NUMBER 26 / 2010 Urbanising Africa: The city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) By: Editors Authors: Alonso Ayala Peter Ahmad Ellen Geurts Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 1 Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) Authors: Peter Ahmad Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs Editors: Alonso Ayala Ellen Geurts IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 2 Introduction This working paper contains a selection of 7 articles written by participants in a Refresher Course organised by IHS in August 2010 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The title of the course was Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited - Ensuring liveable and sustainable inner-cities in Southern African countries: making it work for the poor. The course dealt in particular with inner-city revitalisation in Southern African countries, namely South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Inner-city revitalisation processes differ widely between the various cities and countries; e.g. in Lusaka and Mbabane few efforts have been undertaken, whereas Johannesburg in particular but also other South Africa cities have made major investments to revitalise their inner-cities. The definition of the inner-city also differs between countries; in Lusaka the CBD is synonymous with the inner-city, whereas in Johannesburg the inner-city is considered much larger than only the CBD. -

Legal Notices Wetlike Kennisgewings

. October Vol. 652 Pretoria, 18 Oktober 2019 No. 42771 LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER QPENBARE VERKOPE 2 No. 42771 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 18 OCTOBER 2019 STAATSKOERANT, 18 OKTOBER 2019 No. 42771 3 CONTENTS / INHOUD LEGAL NOTICES / WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE Sales in execution • Geregtelike verkope ....................................................................................................... 12 Gauteng ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Eastern Cape / Oos-Kaap ................................................................................................................ 55 Free State / Vrystaat ....................................................................................................................... 57 KwaZulu-Natal .............................................................................................................................. 63 Limpopo ...................................................................................................................................... 80 Mpumalanga ................................................................................................................................ 82 North West / Noordwes ................................................................................................................... 86 Northern -

Western Province Federations Contact List

WESTERN PROVINCE FEDERATIONS CONTACT LIST Western Province – Aquatics Bellville [email protected] • Brian Reynolds (Pres) • Mya Stein (Sec) • Tanya (Sec) Tel: 021 794 – 3960(h) 021 555 4871 082 461 6581 Cell: 082 882 2617 082 772 6348 [email protected] Fax: 086 5020 969 [email protected] [email protected] Western Province – Basketball [email protected] Western Cape –Boxing (Olympic Style) • Jason Mitchell (Chairperson) • Bernie Manzoni (Sec) • Daniel Miller 073 937 6025 Tel: 021 9752256 Tel: 021 367 3489 [email protected] [email protected] Cell: 073 250 9685 • Ayanda Vumazonke (Sec) 36 Nerine Str 084 405 1030 WP Aerobics & fitness Lentegeur [email protected] • David Oppel (Chairperson) Mitchell’s Plain Tel: 021 919 6713 Western Cape – Blackball Federation Cell: 084 440 4900 Western Province – Amateur Judo • Graham Whitman (Chair) Fax: 021 949 5793 Association 01 Wembley Rd [email protected] • Michael Job (Pres) Wembly Park 52, 18th Avenue 16 Friesland St Kuilsrivier Bellville Oostersee 7580 7530 Parow Cell: 083 258 0961 • Lynnette le Roux 7500 [email protected] 082 572 7451 [email protected] • Michael Alexander (Treasurer) [email protected] Tel: 021 931 7530 w Western Province – Athletics • Lorraine Job Cell: 078 574 2536 • Sue Forge Cell: 083 583 1848 Fax: 086 5411 761 Tel: 021 434 3742 h / 021 699 0615 w [email protected] [email protected] Cell: 083 456 1015 Fax: 086 685 7897 Western Province - Badminton Association Western Province Blow Darts [email protected] • Ingrid Godfrey (Secretary) • Patrick Botto (Chairperson) P O Box 101 P. -

Legal Notices Wetlike Kennisgewings

June Vol. 672 11 2021 No. 44683 Junie ( PART 1 OF 2 ) LEGAL NOTICES II WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER QPENBARE VERKOPE 2 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 CONTENTS / INHOUD LEGAL NOTICES / WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE Sales in execution • Geregtelike verkope ............................................................................................................ 13 Public auctions, sales and tenders Openbare veilings, verkope en tenders ............................................................................................................... 137 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 3 4 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 5 6 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 7 8 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 9 10 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 11 12 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 13 SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE ESGV SALES IN EXECUTION • GEREGTELIKE VERKOPE Case No: 2493/19 "AUCTION" IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA (Western Cape Division, CAPE TOWN) In the matter between: FIRSTRAND BANK LIMITED (REGISTRATION NUMBER: 1929/001225/06), PLAINTIFF AND DERICK ESIAS KOEN (IDENTITY NUMBER: 7703065032080), 1ST DEFENDANT, SONJA