Attitudes, Knowledge and Practices Affecting the Critically Endangered Mariana Crow Corvus Kubaryi and Its Conservation on Rota, Mariana Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTE Dimensions and Composition of Mariana Crow Nests on Rota

Micronesica 29(2): 299- 304, 1996 NOTE Dimensionsand Compositionof Mariana Crow Nests on Rota, Mariana Islands MICHAEL R. LUSK 1 AND ESTANISLAO TAISACAN Division of Fish and Wildlife, Rota, MP 96951. Abstract-From 1992 to 1994 we measured dimensions of 11 Mariana crow (Corvus kubaryz) nests on Rota. The mean nest diameter, nest height, inner cup diameter, and cup depth were 37.2 cm, 15.4 cm, 13.3 cm, and 6.9 cm, respectively. These nests consisted of an outer platform and intermediate cup primarily composed Jasminum marianum, and an inner cup mainly of Cocos nucifera frond fibers and Ficus prolixa root lets. The platforms of two nests contained an average of 200 twigs, with most being 2.1-4.0 mm in diameter and 201-250 mm long. The inter mediate cups averaged 93 components, with most twigs measuring 0.0- 2.0 mm in diameter and 101-150 mm long. Total weight of the two nests averaged 347.5 g, with the following breakdown: platform 284.1 g, in termediate cup 42.1 g, and inner cup 21.3 g. Introduction The Mariana crow ( Corvus kubaryz) is the only corvid in Micronesia and occurs only in forested habitats on two islands in the Marianas, Guam and Rota. It was listed as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1984 (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1984). Although basic information is lacking on all aspects of the life history of the Mariana crow, Jenkins (1983), Tomback (1986), and Michael (1987) describe in varying detail Mariana crow nest construction on Guam and Rota. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

House Crow E V

No. 2/2008 nimal P A e l s a t n A o l i e t 1800 084 881 r a t N Animal Pest Alert F reecall House Crow E V I The House Crow (Corvus splendens) T is also known as the Indian, Grey- A necked, Ceylon or Colombo Crow. It is not native to Australia but has been transported here on numerous occasions on ships. The T N House Crow has signifi cant potential to establish O populations in Australia and become a pest, so it is important to report any found in the wild. NOTN NATIVE PHOTO: PETRI PIETILAINEN E Australian Raven V I T A N Adult Immature PHOTO: DUNCAN ASHER / ALAMY PHOTO: IAN MONTGOMERY Please report all sightings of House Crows – Freecall 1800 084 881 House Crow nimal P A e l s a t n A o l i e t 1800 084 881 r a Figure 1. The distribution of the House Crow including natural t N (blue) and introduced (red) populations. F reecall Description Distribution The House Crow is 42 to 44 cm in length (body and tail). It has The House Crow is well-known throughout much of its black plumage that appears glossy with a metallic greenish natural range. It occurs in central Asia from southern coastal blue-purple sheen on the forehead, crown, throat, back, Iran through Pakistan, India, Tibet, Myanmar and Thailand to wings and tail. In contrast, the nape, neck and lower breast southern China (Figure 1). It also occurs in Sri Lanka and on are paler in colour (grey tones) and not glossed (Figure 3). -

Square Kilometre Array Ecological Assessment Commercial-In-Confidence

AECOM SKA Ecological Assessment A Square Kilometre Array Ecological Assessment Commercial-in-Confidence Appendix A Conservation Categories G:\60327857 - SKA EcologicalSurvey\8. Issued Docs\8.1 Reports\Ecological Assessment\60327857-SKA Ecological Report_Rev0.docx Revision 0 – 28-Nov-2014 Prepared for – Department of Industry – ABN: 74 599 608 295 AECOM SKA Ecological Assessment A-1 Square Kilometre Array Ecological Assessment Commercial-in-Confidence Appendix A Conservation Categories G:\60327857 - SKA EcologicalSurvey\8. Issued Docs\8.1 Reports\Ecological Assessment\60327857-SKA Ecological Report_Rev0.docx Revision 0 – 28-Nov-2014 Prepared for – Department of Industry – ABN: 74 599 608 295 Definitions of Threatened and Priority Flora Species 1 Appendix A – Conservation Categories 1.1 Western Australia Plants and animals that are considered threatened and need to be specially protected because they are under identifiable threat of extinction are listed under the Wildlife Conservation Act (WC Act). These categories are defined in Table 1. Any species identified as Threatened under the WC Act is assigned a threat category using the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List categories and criteria. Species that have not yet been adequately surveyed to warrant being listed under Schedule 1 or 2 are added to the Priority Flora or Fauna Lists under Priority 1, 2 or 3. Species that are adequately known, are rare but not threatened, or meet criteria for Near Threatened, or that have been recently removed from the threatened list for other than taxonomic reasons, are placed in Priority 4 and require regular monitoring. Conservation Dependent species and ecological communities are placed in Priority 5. -

The Australian Raven (Corvus Coronoides) in Metropolitan Perth

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 1997 Some aspects of the ecology of an urban Corvid : The Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) in metropolitan Perth P. J. Stewart Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Stewart, P. J. (1997). Some aspects of the ecology of an urban Corvid : The Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) in metropolitan Perth. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/295 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/295 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Some Vocal Characteristics and Call Variation in the Australian Corvids

72 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 72-82 Some Vocal Characteristics and Call Variation in the Australian Corvids CLARE LAWRENCE School of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 5, Hobart, Tasmania 7001 (Email: [email protected]) Summary Some vocal characteristics and call variation in the Australian crows and ravens were studied by sonagraphic analysis of tape-recorded calls. The species grouped according to mean maximum emphasised frequency (Australian Raven Corvus coronoides, Forest Raven C. tasmanicus and Torresian Crow C. orru with lower-freq_uency calls, versus Little Raven C. mellori and Little Crow C. bennetti with higher-frequency calls). The Australian Raven had significantly longer syllables than the other species, but there were no significant interspecific differences in intersyllable length. Calls of Southern C.t. tasmanicus and Northern Forest Ravens C.t. boreus did not differ significantly in any measured character, except for normalised syllable length (phrases with the long terminal note excluded). Northern Forest Ravens had longer normalised syllables than Tasmanian birds; Victorian birds were intermediate. No evidence was found for dialects or regional variation within Tasmania, and calls from the mainland clustered with those from Tasmania. Introduction Owing largely to the definitive work of Rowley (1967, 1970, 1973a, 1974), the diagnostic calls of the Australian crows and ravens Corvus spp. are well known in descriptive terms. The most detailed studies, with sonagraphic analyses, have been on the Australian Raven C. coronoides and Little Raven C. mellori (Rowley 1967; Fletcher 1988; Jurisevic 1999). The calls of the Torresian Crow C. orru and Little Crow C. bennetti have been described (Curry 1978; Debus 1980a, 1982), though without sonagraphic analyses. -

Genetic Applications in Avian Conservation

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey 2011 Genetic Applications in Avian Conservation Susan M. Haig U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Whitcomb M. Bronaugh Oregon State University Rachel S. Crowhurst Oregon State University Jesse D'Elia U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Collin A. Eagles-Smith U.S. Geological Survey See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Haig, Susan M.; Bronaugh, Whitcomb M.; Crowhurst, Rachel S.; D'Elia, Jesse; Eagles-Smith, Collin A.; Epps, Clinton W.; Knaus, Brian; Miller, Mark P.; Moses, Michael L.; Oyler-McCance, Sara; Robinson, W. Douglas; and Sidlauskas, Brian, "Genetic Applications in Avian Conservation" (2011). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 668. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/668 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Susan M. Haig, Whitcomb M. Bronaugh, Rachel S. Crowhurst, Jesse D'Elia, Collin A. Eagles-Smith, Clinton W. Epps, Brian Knaus, Mark P. Miller, Michael L. Moses, Sara Oyler-McCance, W. Douglas Robinson, and Brian Sidlauskas This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ usgsstaffpub/668 The Auk 128(2):205–229, 2011 The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2011. Printed in USA. SPECIAL REVIEWS IN ORNITHOLOGY GENETIC APPLICATIONS IN AVIAN CONSERVATION SUSAN M. HAIG,1,6 WHITCOMB M. BRONAUGH,2 RACHEL S. -

On the Field Characters of Little and Torresian Crows in Central Western Australia. by PETER J

December ] CURRY: Field Characters of Crows 265 1978 (Wheelwright, H. W.) An Old Bushman 1861. Bush Wanderings of a Naturalist. London. Routledge, Warne and Routledge. Whittell, H . M., 1954. The Literature of Australian Birds. Perth. Paterson Brokensha. Wilson, Edward, 1858. On the Introduction of the British Song Bird. Transactions of the Philosophical Institute of Victoria 2, 77-88. Wilson, Edward, 1860. Letter to the Times, 22 September, 1860. (ZOOLOGICAL AND) ACCLIMATISATION SOCIETY OF VICTORIA 1861-1951 Papers (mostly minutes and reports) Vols. 1-13 (Xerox copies in library of Monash University, Clayton, Victoria). 1861-7. Annual reports, Answers to enquiries, report of dinner, rules and objects, etc. (Bound in Victorian pamphlets, nos. 32, 36, 49, 60 and 129 in LaTrobe Library, State Library of Victoria. 1872-8. Proceedings and reports of Annual Meetings, Vols. 1-5. On the Field Characters of Little and Torresian Crows in Central Western Australia. By PETER J. CURRY, 29 Canning Mills Road Kelmscott, W.A., 6111. The Little Crow Corvus bennetti and the Torresian Crow C. orru are evidently sympatric over a large part of northern and cen tral Australia and are notoriously difficult to separate in the field. Over their respective ranges, morphological similarities and indivi dual variation in size are such that some individuals are extremely difficult to identify even in the hand (Rowley, 1970). Despite various recent references which draw attention to the importance of call-notes and habits in field identification (Rowley, 1973; Readers' Digest, 1976), published information on the subject has generally been very brief. The notes which follow r~sult from field observations made in the Wiluna region of central Western Australia, during eighteen months of almost daily contact with both species. -

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7074/docket-no-fws-hq-mb-2018-0047-fxmb-12320900000-201-ff09m29000-1487074.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 04/16/2020 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2020-06779, and on govinfo.gov Billing Code 4333–15 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 10 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000] RIN 1018–BC67 General Provisions; Revised List of Migratory Birds AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), revise the List of Migratory Birds protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by both adding and removing species. Reasons for the changes to the list include adding species based on new taxonomy and new evidence of natural occurrence in the United States or U.S. territories, removing species no longer known to occur within the United States or U.S. territories, and changing names to conform to accepted use. The net increase of 67 species (75 added and 8 removed) will bring the total number of species protected by the MBTA to 1,093. We regulate the taking, possession, transportation, sale, purchase, barter, exportation, and importation of migratory birds. An accurate and up-to-date list of species protected by the MBTA is essential for public notification and regulatory purposes. DATES: This rule is effective [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. 1 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Eric L. Kershner, Chief of the Branch of Conservation, Permits, and Regulations; Division of Migratory Bird Management; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; MS: MB; 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA 22041-3803; (703) 358-2376. -

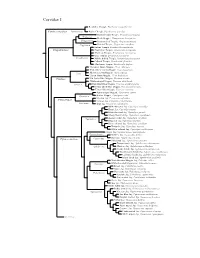

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

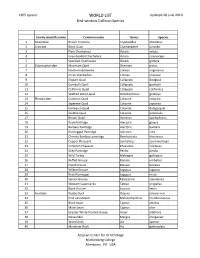

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Aboriginal Bird Names- South Australia

October, 1955 THE S.A. ORNITHOLOGIST 91 ABORIGINAL BIRD NAMES - SOUTH AUSTRALIA Part Two By H. T. CONDON, S.A. Museum WELCOME SWALLOW thindriethindrie, Dieri (Gason) Hirundo neoxena titjeritjera, Aranda (C. Strehlow) . ioisjililki, Ngadj uri (Berndt & Vogels.) duioara, Narangga (Tindale) yerrellyerra, Aranda (Willshire) Ooon-gilga, "Central Australia" (Bates) Most of these names are onomatopaeic. koolgeelga, Kokata (Sullivan) menmenengkuri, 'Narrinyeri' (Taplin) RESTLESS FLYCATCHER mulya mulyayapunie, Dieri (Cason) warrakka, Pangkala (Schurmann) Seisura inquieta worraga, KokatajWirangu (Sullivan) didideilja (or) ditidilja, Narangga (Tindale) The following -names probably refer to this djirba, Wirangu (Bates) species: khinter-khinter, Kokata/Wirangu (Sullivan) mannmanninya, Kaurna (Teich. & Schur.) miduga, Narangga (Howitt) SCARLET ROBIN Petroica multicolor WHITE·BACKED SWALLOW jupi, Ngadjuri (Berndt & Vogels.) Cheramoeca leucosterna tat-kana, Buanditj (Campbell et alia) kaldaldake, 'Narrinyeri' (Taplin) turon go, Warki (Moorhouse) worraga, KokatajWirangu (Sullivan) tuta, "Encounter Bay" (Wyatt) tuttaipitti, Kaurna (Teich. & Schur.) TREE MARTIN Hylochelidon nigricans RED·CAPPED ROBIN wireldutulduti, Wailpi (Hale & Tindale) Petroica goodenovii worraga, KokatajWirangu (Sullivan) choonda, Dieri (Gason) yukourolconi, Wailpi (Hale & Tindale) eeningee-lab-lab, Aranda '(Chewings) eeninjeelabbab (Willshire) MARTIN kummeracheeta, Wirangu (Sullivan) . Hylochelidon sp, -literally 'uncle bird' menmeneng-kuri, 'Narrinyeri' (Taplin) .malitelita, Wailpi