190 English As a Second Language in Malay-Speaking Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study on Sodium Content in Local Foods

Annex I Annex I: Sodium content in non-prepackaged foods by category Food category (Food items included) n Sodium (mg/100g) Avg Std Dev Min Max Condiments and sauces 30 1,183 1,137 310 4,600 Sauce for Siumei/Lomei meat (Charsiew/ Siumei/ Lomei sauce; Ginger puree/ Ginger and shallot puree) 6 2,885 1,495 310 4,600 Curry gravy (Indian; Japanese; Thai)(Solid included) 6 635 135 390 790 White gravy (including mushroom; corn; etc.)(Solid included) 6 485 75 410 580 Asian sauces (Vietnamese sweet and sour sauce; Sauce for nuggets) 6 1,300 597 400 2,100 Gravy for other meat (Black pepper; Onion; Brown) 6 612 229 380 880 Processed meat products 80 1,225 1,250 280 6,800 Siumei/ Lomei chicken (Soy sauce chicken meat) 7 570 262 320 970 Siumei/ Lomei duck/ goose ("Lo shui" duck/goose; Roasted duck/goose) 9 738 347 360 1,400 Other siumei/ lomei poultry ("Lo shui" pigeon; Roasted pigeon) 7 669 301 280 1,000 Siumei/ Lomei pork (Roasted pork/ Roasted suckling pig; "Barbeque" pork) 9 691 193 350 970 Other siumei/ lomei pork (Salted and smoked pork; "Lo Shui" pork meat (ear; trotter; tongue)) 7 1,199 475 590 1,800 product Asian preserved sausages (Canton-style pork sausage/ Liver sausage; Red pork sausage) 5 1,754 775 870 2,700 Western preserved sausages (Meat; Cheese; Cervelat; Pork; Chicken) 4 933 70 840 1,000 Ready-to-eat marinated offal (Ox offals; Chicken liver) 4 585 283 330 990 Ready-to-eat meat balls (Fish ball (fried/boiled); Beef/ Beef tendon ball; Meat stuffed ball; Cuttle 10 744 205 420 980 fish ball; Shrimp ball) Preserved fish and seafood -

Startsmart Parent Guide in 2012

Revised 2020 “In the family … where there is love, there is health.” “In the family … where there is love, there is health.” Foreword Loving our children – Where to start? Nowadays, many parents make early plans for the future of their children. They spend a lot of time, effort and money on choosing schools, foreign language classes or hobby groups for their children, wishing to give their children a quality and comfortable life in the future. Everything that parents do is out of love. Yet, how could children embrace a bright future if they are not in good health? To ensure that children can contribute to society, enjoy their lives and live happily after growing up, it is important for parents to teach them ways of self-care to stay healthy at an early age. In Hong Kong, the problem of childhood obesity is prevalent. The proportion of primary one students being overweight/obese reflects that the problem has already arisen in the pre-primary stage. A lot of research has shown that overweight children are more likely to become obese adults with increased risks of developing chronic diseases (including hypertension, diabetes and heart diseases) and certain types of cancer. Caring and responsible parents should not only create a happy, healthy environment for their children, but also act as role models. In doing so, children are able to develop a healthy lifestyle to protect themselves against diseases related to poor dietary habits or sedentary lifestyles. In the long run, they can avoid unnecessary pain and suffering in adulthood. ⅰ In view of the above, the Department of Health, with the support of various Government departments, education sectors and stakeholders in child health, launched the Campaign and compiled the first edition of StartSmart Parent Guide in 2012. -

House Special Broth Stock Qty Cold Plate Snack Meat Meat Ball Dumpling & Wonton Seafood

#405-5300 No.3 Road, Richmond, B.C., V6X 2X9 Tel: 604-231-8966 Fax: 604-231-8964 MEAT QTY QTY QTY HOUSE SPECIAL BROTH STOCK Premium Lamb Shoulder Slices (reg) 10.99 DUMPLING & WONTON House Special Original Broth 9.99 Premium Lamb Shoulder Slices (small) 7.99 8 Minced Cod Paste Dumpling 5.99 Chef Special Spicy Broth 9.99 Fatty Mutton Slices 9.99 8 Mutton Dumpling 4.99 Half Half (original and spicy) 9.99 Beer Sauce Marinated Mutton 10.99 Vegetarian option available upon request. Premium Angus Beef Hand Sliced (reg) 19.99 8 Pork & Shrimp Dumpling 4.99 Premium Angus Beef Hand Sliced (small) 13.99 Chives & Pork Dumpling 4.99 COLD PLATE QTY 8 Fatty Beef Slices (reg) 10.99 Pickled Garlic 2.99 Veggi & Pork Dumpling 4.99 Fatty Beef Slices (small) 7.99 8 Szhchuan Style Kimchi 3.99 Loin of Beef 9.99 Garlic Seaweed 3.99 Garlic Beef 9.99 Shredded Spicy Potato 3.99 QTY Pork Jowl Slices 8.99 SEAFOOD Tender Pork Slices 8.99 Sea Cucumber Heart 17.99 SNACK QTY Ranch Chicken (Half) 8.99 Mongolian Meaty Bone 5.99 Fresh Sole Fillet Slices 8.99 Tender Chicken Fillet 7.99 Mutton Skewer 5.99 Chicken Mid-Wings 7.99 Jumbo Scallop 12.99 Beef Skewer 5.99 Luncheon Pork 6.99 White Prawn 10.99 Mutton & Beef Skewer 5.99 Fresh Oyster 9.99 Squid Tentacle Skewer 1.50 MEAT BALL QTY Bun Skewer 1.25 15 Mutton Ball 6.99 Mussel 7.99 House Sp Sesame cake 4.99 15 Beef Ball 6.99 Cuttlefish 7.99 Sesame Pastry Cake 3.99 15 Fish Ball 6.99 Squid Tube 7.99 Green Onion Pork Pie 5.99 15 Shrimp Ball 8.99 Mongolian Beef Pie -

ROLLS Crispy Spring Rolls with Shrimp, Pork Shoulder, Glass Noodles

ROLLS crispy spring rolls with shrimp, pork shoulder, glass noodles, carrot 7 crispy vegetarian spring rolls with tofu, tara root, glass noodles, carrot 7 summer rolls with shrimp, rice vermicelli noodle, bean sprouts, mint, lettuce, peanut 7 sauce vegetarian summer rolls with tofu, rice vermicelli noodle, mint, bean sprouts 6.5 pork summer rolls with rice vermicelli, mint, bean sprouts 7 APPETIZERS fried squid with pineapple, jalapenos, cilantros 10 fried chicken wings with sriracha butter dipping sauce 8 shrimp & pork wonton soup with egg noodles, scallions, cilantros, crispy shallots 5.5 fried boneless chicken wings stuffed with crabmeat, shrimp 13 sautéed lemongrass mussels with coconut milk- sriracha chili sauce 15 barbecued pork spareribs with scallions, honey-hoisin sauce 13 SALADS chicken, cabbage, pickled carrots, thai basil, roasted peanuts, fish sauce 8.5 shrimp, cabbage, pickled carrots, thai basil, roasted peanuts, fish sauce 8.5 green papaya, thai basil, crispy shallots, pickled carrot, fried tofu, celery, cucumber, 9 peanuts spicy beef, thai basil, bell peppers, onions, sriracha chili sauce 12 SOUP (note: all soups topped with onions, scallions, cilantros). Add tripe or tendon – additional $2.5 pho tai (beef eye round noodle soup) beef eye round, rice noodle 9 pho tai bo vien (eye round and beefball) eye round, beefball, rice noodle 9.5 pho bo vien (beef ball noodle soup) beefball, rice noodle 9 pho chin (brisket noodle soup) brisket, rice noodle 9 pho chin bo vien (brisket & beefball noodle soup) brisket, beefball, rice -

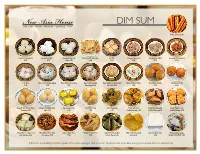

Dim Sum Menu

DIM SUM Fried Culler 3.50 Steam Chicken Buns Steam Pork Buns Steamed Custard Pan Fried Turnip Cake Siu Mai Steamed Spareibs Steamed Beef Ball Steamed Chicken Feet 4.75 4.75 Buns 4.75 4.50 4.50 4.50 5.95 4.50 Har Gao Shrimp Chive Dumplings Zhao Chow Dumplings SteamedVegetable Pork & Shrimp Bean Curd Steamed Beef Triple Fried Shrimp Balls Fried Crab Puffs 4.50 4.50 4.50 Dumplings 4.50 Skin Roll 5.25 5.00 6.50 6.50 Deep Fried Minced Meat Deep Fried Rean Bean Egg Custard Tart Fried Taro Puffs Chive Pancakes Fried Tofu with Fried Eggplant with Green Pepper with Turnover 4.50 Balls 4.50 4.50 4.75 4.75 Stuffed Shrimp 4.50 Stuffed Shrimp 4.50 Stuffed Shrimp 4.50 Sticky Rice in Lotus Leaf Mixed Beef Triple with Oyster Duck Feet Herbal Chicken Feet Salty Pork Sticky Rice Water Chestnut Jelly Coconut Jelly Cake Fried Culler with with Chicken 5.25 Five Spices 7.95 7.95 7.95 in leaf (2pcs) 6.95 Cake 3.90 3.90 Steam Rice Roll 5.25 If there are Food Allergies? Please speak to the owner, manager, chef, or server. Pictures in the menu does not represent actual dish size and portions. CONGEE Beef 7.00 Dim Sum Hours: Monday to Sunday Frog 7.50 If there are Food Allergies? Please speak to Pork 7.00 the owner, manager, chef, or server. Fish Fillet 7.50 Pictures in the menu does not represent Dry Scallop 8.50 actual dish size and portions. -

Nutrient Values of Chinese Dim Sum

Risk Assessment Studies Report No. 17 NUTRIENT VALUES OF CHINESE DIM SUM April 2005 (Revised February 2007) Food and Environmental Hygiene Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region i This is a publication of the Food and Public Health Branch of the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD) of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Under no circumstances should the research data contained herein be reproduced, reviewed, or abstracted in part or in whole, or in conjunction with other publications or research work unless a written permission is obtained from FEHD. Acknowledgement is required if other parts of this publication are used. Correspondence: Risk Assessment Section Food and Environmental Hygiene Department 43/F, Queensway Government Offices, 66 Queensway, Hong Kong. Email: [email protected] ii Contents Page Abstract 2 Objectives 3 Background 3 Scope of Study 5 Method 6 Sampling Plan Laboratory Analysis Data Analysis Results and Discussion 7 Nutrient Contents in Chinese Dim Sum Effects of Adding Sauces in the Boiled Vegetable Effects of Consuming Soup on the Sodium Content of Noodle-in-soup Limitations of the study Conclusion and Recommendations 16 References 21 Annex I: Recommendations of WHO and FAO on Nutrient Intake 22 Annex II: Nutrition and Health 24 Annex III: Chinese dim sum analyzed in this study 27 Annex IV: Testing Methods for the Determining Nutrient Contents 30 in Foods iii Annex V: Nutrient Contents of Chinese Dim Sum (per 100 g) 32 Annex VI: Nutrient Contents of Chinese Dim Sum (per 37 Serving/Unit) Annex VII: Nutrient Contents of Three Chinese Dim Sum Menus 43 Annex VIII: Criteria for Evaluation of Nutrient Values of Chinese 46 Dim Sum Sets iv Risk Assessment Studies Report No. -

PREPARED by ROYAL MALAYSIAN CUSTOMS DEPARTMENT for Further Enquiries, Please Contact Customs Call Center

PREPARED BY ROYAL MALAYSIAN CUSTOMS DEPARTMENT For further enquiries, please contact Customs Call Center : 1 300 88 8500 (General Enquiries) Operation Hours Monday - Friday (8.30 a.m – 7.00 p.m) email: [email protected] For classification purposes please refer to Technical Services Department. This Guide merely serves as information. Please refer to Sales Tax (Goods Exempted From Tax) Order 2018 and Sales Tax (Rates of Tax) Order 2018. Page 2 of 130 NAME OF GOODS HEADING CHAPTER EXEMPTED 5% 10% Live Animals (Subject to an import/export license from the relevant authorities) Live Bee (Lebah) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Boar (Babi Hutan) 01.03 01 ✔ Live Buffalo (Kerbau) 01.02 01 ✔ Live Camel (Unta) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Cat (Kucing) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Chicken (Ayam) 01.05 01 ✔ Live Cow (Lembu) 01.02 01 ✔ Live Deer (Rusa) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Dog (Anjing) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Duck (Itik) 01.05 01 ✔ Live Elephant (Gajah) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Frog (Katak) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Geese (Angsa) 01.05 01 ✔ Live Goat (Kambing) 01.04 01 ✔ Live Horse (Kuda) 01.01 01 ✔ Live Oxen 01.02 01 ✔ Live Pig 01.03 01 ✔ Live Quail (Puyuh) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Rabbit (Arnab) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Sheep (Biri-biri) 01.04 01 ✔ Live Turkey (Ayam Belanda) 01.05 01 ✔ Meat & Edible Meat Offal (Subject to an import/export license from the relevant authorities) Beef Bone (Tulang Lembu) (Fresh/ Chilled) 02.01 02 ✔ Beef Bone (Tulang Lembu) (Frozen) 02.02 02 ✔ Belly (Of Pig) (Fresh/ Chilled/ Frozen) 02.03 02 ✔ Boneless Ham (Of Pig) (Fresh/ Chilled/ 02.03 02 ✔ Frozen) This Guide merely serves as information. -

Rice Plates ( Cơm Phần ) Other Rice

BEEF NOODLE SOUP (PHỞ) SALADS ( GỎI ) SANDWICHES ( BANH MI ) 1) Beef Combination Pho............................................. L $12.99 19) Chicken Salad.................................................................... $10.00 Choose ONE of the following meat choices: BBQ Chicken, (includes rare steak, well done brisket, beef ball, tendon, and tripe) Boneless chicken tossed with fresh romaine lettuce, tomatoes, BBQ Pork, or Lemon Grass Chicken on french bread with round onions, and house made vinaigrette dressing. pickled vegetables, parsley, cucumber, lettuce, jalapeno, 2) Steak pho.................................................................. L $12.30 and mayonnaise. 20) Green Papaya Salad........................................................... $11.00 36) Sandwich...........................................................$10.99 3) Rare steak and well done brisket pho....................... L $12.24 Shredded green papaya, shrimp, and pork with fresh chopped herbs topped with roasted peanuts in house made dressing. Served as a combo meal with small pho soup and shrimp 4) Rare steak and beef balls pho................................... L $12.24 chips. (Add an over easy egg for $1.50) 5) Beef balls pho........................................................... L $12.24 21) Watercress Tofu Salad....................................................... $11.00 Watercress, lettuce, sauteed beef, tofu, and fresh tomatoes in 6) Steak and flank pho.................................................. L $12.24 house made vinaigrette dressing. -

Chinese Cuisine 中餐

EGG FOO YOUNG Drinks Coke .....................................................1.50 Sprite ...................................................1.50 WABI Q Hot Pot To Go Vegetable (3) ...................... $7.95 Individually portioned & pre cooked hot pot. Chinese Diet Coke .............................................1.50 Chicken (3) .......................... $7.95 中餐 BBQ (3) ................................ $7.95 Ramune (Original, Grape, Strawberry, Orange) 3.50 Cuisine Beef (3) ................................ $9.95 $14.95 CARRY OUT / DELIVERY ONLY Shrimp (3) ......................... $10.95 House Special Cheese Berry .......................................5.95 • Vegetable mix includes: enoki mushroom, House Special (3) .............. $11.95 Cheese Mango ....................................5.95 630.226.1833 148 W Boughton Rd. 60440 Bolingbrook, IL (Chicken, Beef and Shrimp) napa cabbage, potato slices, sweet corn, APPETIZERS Cheese Peach ......................................5.95 Vegetable Egg Roll (2) ....................$3.49 broccoli, & zucchini. Served with sweet Fruity Orange ......................................5.95 DINE IN | CARRY OUT | DELIVERY pickles, udon noodles, & rice. Wabi Q Egg Roll (2) .........................$3.49 NOODLE Fruity Grapefruit ................................5.95 .com Crab Rangoon (6) ............................$6.49 Vegetable Lo Mein ............ $8.95 Fruity Pineapple .................................5.95 Chicken Wing (6) .............................$7.50 • Please select 2 sauces from the following: -

Appetizers & Starters

Welcome to 68 Crawfish Express where your food is made to order with the freshest local ingredients available. We hope you enjoy our eclectic menu featuring Cajun and South East Asian favorites. Our restaurant serves neighborhood cuisine - combining the highest quality items in dishes influenced by the flavors of the Gulf Coast Vietnam Thailand and Malaysia. OUR FAMOUS SAUCES & DRESSINGS 68 House Butter: Garlic Butter with A Peppery, Sweet and Spicy Kick 68 House Sauce: Creamy, Spiced Remoulade Style Sauce Traditional Sauce: Buffalo, BBQ, Lemon Pepper, Garlic Butter, Parmesan & Garlic, Honey, Tamarind Spicy, Vietnamese Sweet & Sour, Sriracha, Hoisin, Teriyaki, Vinaigrette, Ranch, Blue Cheese. APPETIZERS & STARTERS 1. Egg Drop Soup ........................................................................$4.99 Lightly seasoned chicken filled with delicious egg “ribbons,” carrot, peas, and chicken white meat, and served with crispy fried wonton shell. 2. Hot and Sour Soup ................................................................$4.99 Our hot and sour soup made from savory long-shimmered 1 chicken broth filled with pork, tofu, wood ear mushroom, and enoki mushroom, and served with crispy fried wonton shell. 2 3. Spring Rolls (2) .......................................................................$5.99 Shrimp and pork, lettuce, herbs, bean sprouts and vermicelli rolled in rice paper, served with peanut sauce. 4. Satay/Skewers (2) 3 Chicken .......................................................................................$5.99 -

Ha Long Phở Noodle House! We Would Like to Share Our Family’S Tradition of Eating Vietnamese Phở with You, One of Our Favorite Comfort Foods

Welcome to Ha Long Phở Noodle House! We would like to share our family’s tradition of eating Vietnamese Phở with you, one of our favorite comfort foods. We hope that when you enter our restaurant you escape into an oasis where you enjoy our food and experience quality and freshness in a contemporary setting. You will take with you the joy of being a Phởnatic (that’s if you are not one already). For more information, visit us at www.halongnoodle.com represents signature dish BEEF NOODLE SOUP (Phở) 1) Beef Combination Phở (Phở Đặc Biệt) Med. $11.99 Lrg. $12.99 (includes rare steak, well done brisket, beef ball, tendon, and tripe) 2) Steak Phở (Phở Tái) Med. $11.30 Lrg. $12.30 3) Steak and Brisket Phở Med. $11.24 Lrg. $12.24 4) Steak and Beef Balls Phở Med. $11.24 Lrg. $12.24 5) Beef Balls Phở Med. $11.24 Lrg. $12.24 6) Steak and Flank Phở Med. $11.24 Lrg. $12.24 7) Steak and Fat Brisket Phở Med. $11.24 Lrg. $12.24 8) Steak and Book Tripe Phở Med. $11.24 Lrg. $12.24 9) Steak and Tendon Phở Med. $11.55 Lrg. $12.55 10) Choice Phở (Limit 3 choices) Med. $11.99 Lrg. $12.99 Steak, beef balls, flank, brisket, fat brisket, tendon, tripe, firm tofu, fried tofu, chicken, broccoli, and/or cabbage (Want more than 3 choices? Great! Just add an additional $1). Squid, shrimp, and/or fish cake (add $1.00) *May substitute for egg noodle $1, Large only for take out orders Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish or eggs may increase your risk of food borne illness OTHER Phở 11) Plain Phở (Rice noodle in phở broth) Med. -

Bamboo Menu Spring 2021 R

APPETIZERS SOUPS RICE & NOODLES 1. Spring Rolls - Gỏi Cuốn ..............................................................$10 12. Wonton Soup....................................................................... Cup $5 Choice of Protein: Chicken or Pork $16 | Beef, BBQ or Roast Pork $17 Shrimp, Pork, Vermicelli Noodles, Lettuce, Bean Sprouts ..........................................................................................Bowl $10 Shrimp $18 | Meat Combo (Chicken, Beef, & Shrimp) $24 and Mint wrapped in Rice Paper Pork and Shrimp Wontons, Spinach, Green Onions and Seafood Combo (Shrimp, Scallop, & Squid) $24 Cilantro in a Hong Kong Style Chicken Broth 2. Szechuan Wontons with Chili Oil ..............................................$10 23. Fried Rice Pork and Shrimp Wontons topped with Chili Oil 13. Sinigang na Hipon ....................................................................$10 Egg, Green Peas, Carrots, Scallions, and Soy Sauce 3. Imperial Rolls – Chả Giò ............................................................$12 A sour Shrimp Soup in a Tamarind based Broth with 24. XO Style Fried Rice Mixture of Shrimp, Pork, and Vegetables wrapped Onion, Tomato, Okra, Green Beans, Daikon and Spinach Egg, Green Onion and XO Sauce in Rice Paper and Fried 25. Thai Styled Fried-Kao Pad Kapoa Kai 4. Salt and Pepper Chicken Wings.................................................$12 NOODLE BAR Egg, Yellow Onion, Bell Pepper, Thai Chili, and Basil Fried Chicken Wings tossed in an Asian Style Choice of Egg Noodles, Rice Noodles, or Chow