1. Cover Page – Characterization of the Catch by Swordfish Buoy Gear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Monday, October 2, 2006 Part II Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 50 CFR Parts 300, 600, and 635 Atlantic Highly Migratory Species; Recreational Atlantic Blue and White Marlin Landings Limit; Amendments to the Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Tunas, Swordfish, and Sharks and the Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Billfish; Final Rule VerDate Aug<31>2005 18:21 Sep 29, 2006 Jkt 208001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\02OCR2.SGM 02OCR2 rwilkins on PROD1PC63 with RULES_2 58058 Federal Register / Vol. 71, No. 190 / Monday, October 2, 2006 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ADDRESSES: Copies of the Final the Environmental Protection Agency Consolidated HMS FMP and other (EPA) published the Notice of National Oceanic and Atmospheric relevant documents are available from Availability (NOA) for the Draft Administration the Highly Migratory Species Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) Management Division website at and the accompanying Draft 50 CFR Parts 300, 600, and 635 www.nmfs.noaa.gov/sfa/hms or by Consolidated HMS FMP (70 FR 48705). contacting Karyl Brewster-Geisz at 301– The 60-day comment period on the [Docket No. 030908222-6241-02; I.D. 713–2347. proposed rule was initially open until 051603C] FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: October 18, 2005. However, because Karyl Brewster-Geisz, Margo Schulze- many of NMFS’ constituents were RIN 0648–AQ65 Haugen, or Chris Rilling at 301–713– adversely affected by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, and the resultant Atlantic Highly Migratory Species; 2347 or fax 301–713–1917; Russell Dunn at 727–824–5399 or fax 727–824– cancellation of three public hearings in Recreational Atlantic Blue and White the Gulf of Mexico region, NMFS Marlin Landings Limit; Amendments to 5398; or Mark Murray-Brown at 978– 281–9260 or fax 978–281–9340. -

IOTC–2013–WPEB09–41 Buoy Gear

IOTC–2013–WPEB09–41 Buoy gear – a potential for bycatch reduction in the small-scale swordfish fisheries: a Florida experience and Indian Ocean perspective Evgeny V. Romanov(1)*, David Kerstetter(2); Travis Moore(2); Pascal Bach(3) (1) PROSPER Project (PROSpection et habitat des grands PÉlagiques de la ZEE de La Réunion), CAP RUN – ARDA, Magasin n°10 – Port Ouest, 97420 Le Port, Ile de la Réunion, France. (2) Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center, 8000 North Ocean Drive Dania Beach, FL 33004 USA. (3) IRD, UMR 212 EME „Ecosystèmes Marins Exploités‟, Centre de Recherche Halieutique Méditerranéenne et Tropicale Avenue Jean Monnet, BP 171, 34203 Sète Cedex, France. * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected], Tel : +262 (0) 262 43 66 10, Fax: +262 (0) 262 55 60 10 Page 1 of 12 IOTC–2013–WPEB09–41 ABSTRACT A swordfish buoy gear, an innovative fishing practice developed in USA in early 2000s, provide a possibility of direct swordfish targeting yielding high CPUE of target species and very low bycatch levels. Here we present a summary of US experience and discuss potential application of this gear in the Indian Ocean region in the perspective of small-scale fisheries development and bycatch reduction. Introduction Heavy exploitation of swordfish in the Atlantic Ocean during 1980s – early 1990s led to an overfished state in both the North Atlantic and South Atlantic stocks (ICCAT, 2009). High levels of juvenile bycatch in certain areas (in particular, the Florida Straits between Florida, Cuba, and the Bahamas) was considered as a major detrimental factor for the stock sustainability. -

Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines

Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines 著者 KAWAMURA Gunzo, BAGARINAO Teodora journal or 鹿児島大学水産学部紀要=Memoirs of Faculty of publication title Fisheries Kagoshima University volume 29 page range 81-121 別言語のタイトル フィリピン, パナイ島の漁具漁法 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10232/13182 Mem. Fac. Fish., Kagoshima Univ. Vol.29 pp. 81-121 (1980) Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines*1 Gunzo Kawamura*2 and Teodora Bagarinao*3 Abstract The authors surveyed the fishing methods and gears in Panay and smaller neighboring islands in the Philippines in September-December 1979 and in March-May 1980. This paper is a report on the fishing methods and gears used in these islands, with special focus on the traditional and primitive ones. The term "fishing" is commonly used to mean the capture of many aquatic animals — fishes, crustaceans, mollusks, coelenterates, echinoderms, sponges, and even birds and mammals. Moreover, the harvesting of algae underwater or from the intertidal zone is often an important job for the fishermen. Fishing method is the manner by which the aquatic organisms are captured or collected; fishing gear is the implement developed for the purpose. Oftentimes, the gear alone is not sufficient and auxiliary instruments have to be used to realize a method. A fishing method can be applied by means of various gears, just as a fishing gear can sometimes be used in the appli cation of several methods. Commonly, only commercial fishing is covered in fisheries reports. Although traditional and primitive fishing is done on a small scale, it is still very important from the viewpoint of supply of animal protein. -

Catalogue 2020 (€)

CARP TRADE CATALOGUE 2020 (€) @starbaits_official Starbaits France STARBAITS TV starbaits.com TRADE CATALOGUE (€) - CARP 2020 EDITORIAL Sensas groups together 4 major brands that are market leaders in European leisure fishing. Our flagship carp brand is STARBAITS. Our product range has evolved over the years in close collaboration with our field testers. The result is an exciting and innovative range of carp tackle and baits that is at the cutting edge of modern angling. Our Pro Fishing book is designed so that retailers can advise customers on exactly what products they need and serves as a logistics tool to help with smooth ordering. Our 2020 catalogue reflects our commitment to our retailers. It contains a great mix of classic best sellers and innovative and exciting new products that are sure to make 2020 a great year of us all. BAITS PERFORMANCE CONCEPT...................................................5 FLUORO LIGHT POP UPS ���������������������������������������������������28 PROBIOTIC �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 14 PREPARATION X �������������������������������������������������������������������� 30 FEEDZ ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 20 EAZI STICK MIX �����������������������������������������������������������������������32 GRAB AND GO �������������������������������������������������������������������������24 ADD IT ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������33 COOKED -

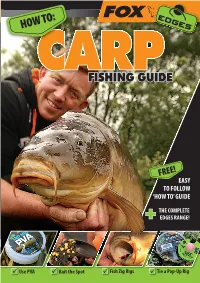

Fox Rig Guide 5 UK.Pdf

HOW TO: CARP FISHING GUIDE mini Swinger FREE! EASY TO FOLLOW ‘HOW TO’ GUIDE THE COMPLETE EDGES RANGE! Use PVA Bait the Spot Fish Zig Rigs Tie a Pop-Up Rig Fox Rig Guide 2018_1-13.indd 1 14/05/2018 10:45:26 HOW TO: CARP FISHING GUIDE WELCOME... to the brand-new Edges ‘How To’ Guide your one-stop shop for mastering the basics of carp shing. The aim of this new guide is to arm you with lots of short bursts of information that will not only help you to catch more carp but also ensure that when you do catch the sh they are cared for correctly too. We have focussed on making the guide very picture-heavy to give lots of visual guidance on how to master a number of tactics. Often much of the information in circulation these days be it in magazines or online is aimed at the more experienced angler and takes many of the basics for granted so we were keen to strip things back and help any newcomers to carp shing to get things right from the o ! The second half of the guide is a classi ed look at our whole Edge range of accessories, for those of you in the market for new accessories that have been designed by carp anglers to help other carp anglers catch more carp you are sure to nd this section very valuable... We really hope you enjoy what’s in store for you over the coming pages... UK Headquarters European Distribution Centre foxint.com 1 Myrtle Road, Brentwood, Transportzone Meer, Riyadhstraat 39, Essex, CM14 5EG 2321 Meer, Belgium /foxInternational Free Fishing Guide not for re-sale. -

Fishermen Engagement in Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas a Key Element to the Success of Artisanal Fisheries Management

REPORT 2014 FISHERMEN ENGAGEMENT IN MEDITERRANEAN MARINE PROTECTED AREAS A key element to the success of artisanal fisheries management WWF -- FishermenAires Marines Engagement Protégées in Mediterraneanet Pêche artisanale Marine - page Protected 53 Areas - page 1 WWF - Aires Marines Protégées et Pêche artisanale - page 1 EDITORS The WWF is the largest global conservation organi- sation. It has more than 5 million donors throughout the world. The organisation has an operational network in 100 countries offering 1,200 nature protection programmes. WWF’s mission is to halt and then reverse the process of degradation of the planet. www.wwf.fr The MedPAN North project is a transnational European project whose general aim is to improve the effectiveness MEDPAN of the managementPROJET of the marine protected areas of the NORTH north Mediterranean.MEDPAN It is conducted under the aus- pices of the MedPAN network and is coordinated by the PROJECT WWF France. ItNORD unites 12 partners from 6 European countries that border the Mediterranean: Spain, France, Greece, Italy, Malta and Slovenia. The project is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund Med Programme, and has a budget of €2.38 million. The project began in July 2010 and will end in June 2013. www.medpannorth.org Port-Cros National Park is a marine, coastal and insular national park. It was established in 1963 and is the first national marine park created in Europe. http://www.portcrosparcnational.fr AUTHORS The ECOMERS research laboratory of the University Nice-Sophia Antipolis -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

La Roche Students Are Not As Dry As the Campus

The La Roche Courier March 27, 2015 La Roche College • 9000 Babcock Boulevard • Pittsburgh, PA 15237 • 412.847.2505 Vol. 19, Issue 5 Are religion and science conflicting? By Sydney Harsh Science Writer cience or religion? Who’s right in the law of causality, he said, can- and who’s wrong? not accept that a God (or divine be- One hundred members of ing) is controlling or manipulating Sthe La Roche College community, the universe.” including students, faculty, and staff Out of the 70 percent who said responded to a survey about their they believe there is a connection be- beliefs on science and religion. The tween science and religion, 52 per- survey found that 70 percent of La cent said they are religious. Roche College students, faculty, and “I’ve been a Christian all my life, staff believe there is a connection and nothing has led me to believe between science and religion. They much against it,” Thomas Carney, a responded to the survey in February. sophomore computer science major, “As a scientist, it seems as though, said. in general, religion is always trying Fifteen out of 100 La Roche stu- to keep science down,” Dr. Becky dents, faculty, and staff said they are Bozym, chemistry professor, said. religious personally, but not publi- Matthew Puller, senior English cally. However, 38 out of 52 religious studies: language and literature ma- students, faculty, and staff said sci- jor, said, “They have a bad relation- ence and religion are in conflict. ship right now, at least for the most “They don’t have to be,” fresh- part. -

Quality Carp Tackle for Monster Specimens. High Quality Rods and Reels, Tried and Tested Accessories, Irresistible Baits – All Combined with a Cool Image

Quality carp tackle for monster specimens. High quality rods and reels, tried and tested accessories, irresistible baits – all combined with a cool image. Radical is the epitomy of modern carp sport par excellence. CONTENTS REELS RA 3 RODS RA 4 ACCESSORIES RA 8 Tent & Brolly RA 38 Ritual SLO RA 3 Old School III Traditional RA 4 Boilies & Additive RA 8 Tent & Bed Chair RA 40 Old School III Hard River RA 4 Display RA 27 Accessories RA 42 Long Range RA 4 Tiger Nuts RA 28 Landing Nets RA 42 Warchild III RA 6 Lines & Rigs RA 28 Sticker RA 44 Warchild Tele Carp III RA 6 Accessories, Leads & Tools RA 30 Warchild Spod RA 6 Bite Alarm RA 32 Bank Sticks, Rod Pods RA 33 Holdall, Carryal, Bags & Bowls RA 35 STANDARD TECHNICAL EQUIPMENT: · Large-surface multi-disc front drag system · CNC stainless steel handle · Anti-twist line roller · Powerful gears · Aluminium Long Stroke™ spool · Aluminium spare spool · Wormshaft oscillation system RITUAL SLO Large waters and monster fish require the ultimate fighting equipment. Now, carp anglers can present their bait where others cannot even begin to look. The Ritual SLO also impresses with its high-performance gears, making it your future partner for extreme requirements. Thanks to the slow spool stroke, line distribution is also of the highest standard, allowing the thinnest braids to be used and flow effortlessly from the spool. Code Model m / mm Gear Ratio Retrieve BB Drag F. Weight Spare Spool Model m / mm Material 0354 070 1070 330 / 0,40 4,9:1 102 cm 10 10,0 kg / 22 lbs 715 g 0987 110 Sp.Spool Ritual SLO 1070 330 / 0,40 Alu 0354 080 1080 420 / 0,40 4,9:1 105 cm 10 10,0 kg / 22 lbs 745 g 0987 111 Sp.Spool Ritual SLO 1080 420 / 0,40 Alu RA2 RA3 CARP RODS Code Model Length Sections C.W. -

English Police Fly Fishing Association River Championship Rules

English Police Fly Fishing Association River Championship Rules The two-day match will be fished in four sessions across two beats, with each competitor fishing both a morning and afternoon session on each beat. Fishing will be carried out in the spirit of, and with respect for, the traditions of the sport. Trout and grayling are the only permitted species. Catch and release will apply with all fish being carefully returned to the river, making sure they can swim away before release. The match organiser, hereinafter referred to as the ‘organiser’ will fix the hours of fishing, divide the competition venue into beats, advise competitors of any venue specific rules, and conduct the draw for both pairings and beats. Within drawn pairings, each competitor will act as their partners controller, and will be responsible for ensuring adherence to the rules and that fish measurement and scorecard completion is done with accuracy. Competitors must use artificial flies on barbless or de-barbed single hooks. Not more than three flies shall be mounted on a cast. Flies may be artificially weighted. Hooks will measure not more than five-eighths of an inch overall, including the eye. The overall length of the fly shall not exceed fifteen-sixteenths of an inch. Flies may be of any pattern and material and may be fished floating or sunk. Attractor chemicals and the use of light emitters are debarred. A competitor may use only one rod at a time (maximum length 12 feet) but may have a second ready mounted as a spare. Leaders must not exceed two rod lengths in length. -

A Brief Discourse Regarding Collllllon Characteristics of Fishing Clubs and Their Men1bers by Richard G. Bell

A Mother Club, a Mystery, and Best of the Worsts Man's life is but vain; For 'tis subject to pain, And sorrow, and short as a bubble; 'Tis a hodge-podge of business and money and ca re, and care and money and tro uble. But we'll take no care when the weather proves fair; Nor will we vex now though it rain; We'll banish all sorrow and sing to tomorrow, and angle and angle again. hus singeth Walton and friends as recorded in The Compleat Angler. Groups of anglers bonding over com- Tmon experience and common water is as old as . .. well, at least as old as Walton, with Thatcht-House being dubbed the Mother Club by author Richard G. Bell. In "Common Threads among the Gold: A Brief Discourse Regarding Common Characteristics of Fishing Clubs and Their Members," Bell begins with the Bible and Berners for stories of fishermen, angling, and attitude. But, he claims, it is Walton who gives us "clubness." Bell's article, originally a presentation to the Lime- stone Club of East Canaan, Connecticut, is filled with stories and songs of anglers banding together for the sake of tradition to fish, eat, drink, be merry, exaggerate, and complain. This rather lively piece begins on page 2. About ten years ago, Frederick Buller found a collection of flies at a rummage sale in a box marked "Unusual Salmon Flies (circa 188o) ." Since then, he's been researching these flies and asking the opinions of others. The flies are, in fact, still a bit of a mystery. -

Celebrating Our 24TH Year! 2020

Catfish Connection Celebrating our 24TH year! 2020 Hooks and Swivels shown actual size! We sell everything but the fish!! catfishconnection.com PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE DUE TO IMPORT TARRIFFS - PRICES CAN BE CONFIRMED BY CHECKING OUR ON-LINE CATALOG OR CALLING 1-800-929-5025 TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE ITEM PAGE ALARM BELLS, BITE INDICATORS 92 KNIFE SHARPENERS 90 ASSORTMENTS, Hook, Swivel 43,86 LANDING NETS 91 BAIT ADDITIVES, ATTRACTANTS 29 CATFISH LEAD MELTING POTS 53 BATTERIES 103 LEAD SINKERS 57-59 BLACK LIGHTS 93 LIGHTED BOBBERS/LIGHTSTICKS 48-49 BOAT ACCESSORIES, DECALS 98-99 LINE ACCESSORIES 100 BOBBER STOPS 52 LINE SPOOLER, STRIPPER 100 BOBBERS 48-52 LIVE BAGS (TOURNAMENT) 37 BOOKS 103 MARKER BUOYS 98 BRAIDED FISHING LINE 24-26 MINNOW BUCKETS 118-119 BRANCH/BRUSH GRIPPER 98 MINNOW TRAPS 34-35 CAN HUGGY 103 MONOFILAMENT FISHING LINE 26-28 CARP BAIT 39 CATFISH NIGHT FISHING EQUIPMENT 93 CAST NETS 36-37 PLANER BOARD 98 CATFISH RIG 47 PLIERS 87 CHUM 29 REEL HANDLES, OIL/GREASE 101 CLOTHING/RAINGEAR 102 REEL COVERS 101 COMBOS 11-13 REELS 14-23 CRAWFISH TRAP 34 ROD STORAGE/ACCESSORIES 99 CRAWLER CARRIERS 144 ROD HOLDERS 94-96 DECALS 98 RODS 1-10 DIP BAITS 40 SABIKI RIGS 46-47 DIP and TUBE WORMS 41-42 CATFISH SCALES 97 DIP BAIT ACCESSORIES 42 SEINES 35 DO-IT MOLDS 54-55 SHAD TRAWL 37 DOUGH BAIT HOOKS 38 SINKER SLIDERS and BUMPERS 56 DOUGH BAITS 39 SINKERS 57-59 DRIFT SOCK 98 SKINNERS 87 E-CAT ROD 2 STRINGERS 29 ELECTRIC FILLET KNIVES 88 SWIVELS 43-46 FILLET BOARDS 89 T-SHIRTS 102 FILLET KNIVES 88-89 TACKLE BOXES 143 FISH GRIPPERS 97 CATFISH