Clinical Evaluation and Optimal Management of Cancer Cachexia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

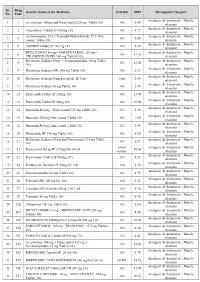

PMBJP Product.Pdf

Sr. Drug Generic Name of the Medicine Unit Size MRP Therapeutic Category No. Code Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 1 1 Aceclofenac 100mg and Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 10's 8.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 2 2 Aceclofenac Tablets IP 100mg 10's 10's 4.37 relaxants Acetaminophen 325 + Tramadol Hydrochloride 37.5 film Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 3 4 10's 8.00 coated Tablet 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 4 5 ASPIRIN Tablets IP 150 mg 14's 14's 2.70 relaxants DICLOFENAC 50 mg+ PARACETAMOL 325 mg+ Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 5 6 10's 11.30 CHLORZOXAZONE 500 mg Tablets 10's relaxants Diclofenac Sodium 50mg + Serratiopeptidase 10mg Tablet Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 6 8 10's 12.00 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 7 9 Diclofenac Sodium (SR) 100 mg Tablet 10's 10's 6.12 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 8 10 Diclofenac Sodium 25mg per ml Inj. IP 3 ml 3 ml 2.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 9 11 Diclofenac Sodium 50 mg Tablet 10's 10's 2.90 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 10 12 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 120mg 10's 10's 33.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 11 13 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 90mg 10's 10's 25.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 12 14 Ibuprofen 400 mg + Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 15's 5.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 13 15 Ibuprofen 200 mg film coated Tablet 10's 10's 1.80 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 14 16 Ibuprofen 400 mg film coated Tablet 10's 15's 3.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic -

Megestrol Acetate/Melengestrol Acetate 2115 Adverse Effects and Precautions Megestrol Acetate Is Also Used in the Treatment of Ano- 16

Megestrol Acetate/Melengestrol Acetate 2115 Adverse Effects and Precautions Megestrol acetate is also used in the treatment of ano- 16. Mwamburi DM, et al. Comparing megestrol acetate therapy with oxandrolone therapy for HIV-related weight loss: similar As for progestogens in general (see Progesterone, rexia and cachexia (see below) in patients with cancer results in 2 months. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38: 895–902. p.2125). The weight gain that may occur with meges- or AIDS. The usual dose is 400 to 800 mg daily, as tab- 17. Grunfeld C, et al. Oxandrolone in the treatment of HIV-associ- ated weight loss in men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- trol acetate appears to be associated with an increased lets or oral suspension. A suspension of megestrol ace- controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 41: appetite and food intake rather than with fluid reten- tate that has an increased bioavailability is also availa- 304–14. tion. Megestrol acetate may have glucocorticoid ef- ble (Megace ES; Par Pharmaceutical, USA) and is Hot flushes. Megestrol has been used to treat hot flushes in fects when given long term. given in a dose of 625 mg in 5 mL daily for anorexia, women with breast cancer (to avoid the potentially tumour-stim- cachexia, or unexplained significant weight loss in pa- ulating effects of an oestrogen—see Malignant Neoplasms, un- Effects on carbohydrate metabolism. Megestrol therapy der Precautions of HRT, p.2075), as well as in men with hot 1-3 4 tients with AIDS. has been associated with hyperglycaemia or diabetes mellitus flushes after orchidectomy or anti-androgen therapy for prostate in AIDS patients being treated for cachexia. -

U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports / Vol. 65 / No. 3 July 29, 2016 U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations and Reports CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................1 Methods ....................................................................................................................2 How to Use This Document ...............................................................................3 Keeping Guidance Up to Date ..........................................................................5 References ................................................................................................................8 Abbreviations and Acronyms ............................................................................9 Appendix A: Summary of Changes from U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010 ...........................................................................10 Appendix B: Classifications for Intrauterine Devices ............................. 18 Appendix C: Classifications for Progestin-Only Contraceptives ........ 35 Appendix D: Classifications for Combined Hormonal Contraceptives .... 55 Appendix E: Classifications for Barrier Methods ..................................... 81 Appendix F: Classifications for Fertility Awareness–Based Methods ..... 88 Appendix G: Lactational -

Combined Estrogen–Progestogen Menopausal Therapy

COMBINED ESTROGEN–PROGESTOGEN MENOPAUSAL THERAPY Combined estrogen–progestogen menopausal therapy was considered by previous IARC Working Groups in 1998 and 2005 (IARC, 1999, 2007). Since that time, new data have become available, these have been incorporated into the Monograph, and taken into consideration in the present evaluation. 1. Exposure Data 1.1.2 Progestogens (a) Chlormadinone acetate Combined estrogen–progestogen meno- Chem. Abstr. Serv. Reg. No.: 302-22-7 pausal therapy involves the co-administration Chem. Abstr. Name: 17-(Acetyloxy)-6-chlo- of an estrogen and a progestogen to peri- or ropregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione menopausal women. The use of estrogens with IUPAC Systematic Name: 6-Chloro-17-hy- progestogens has been recommended to prevent droxypregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione, acetate the estrogen-associated risk of endometrial Synonyms: 17α-Acetoxy-6-chloro-4,6- cancer. Evidence from the Women’s Health pregnadiene-3,20-dione; 6-chloro-Δ6-17- Initiative (WHI) of adverse effects from the use acetoxyprogesterone; 6-chloro-Δ6-[17α] of a continuous combined estrogen–progestogen acetoxyprogesterone has affected prescribing. Patterns of exposure Structural and molecular formulae, and relative are also changing rapidly as the use of hormonal molecular mass therapy declines, the indications are restricted, O CH and the duration of the therapy is reduced (IARC, 3 C 2007). CH3 CH3 O C 1.1 Identification of the agents CH3 H O 1.1.1 Estrogens HH For Estrogens, see the Monograph on O Estrogen-only Menopausal Therapy in this Cl volume. C23H29ClO4 Relative molecular mass: 404.9 249 IARC MONOGRAPHS – 100A (b) Cyproterone acetate Structural and molecular formulae, and relative Chem. -

Role of Androgens, Progestins and Tibolone in the Treatment of Menopausal Symptoms: a Review of the Clinical Evidence

REVIEW Role of androgens, progestins and tibolone in the treatment of menopausal symptoms: a review of the clinical evidence Maria Garefalakis Abstract: Estrogen-containing hormone therapy (HT) is the most widely prescribed and well- Martha Hickey established treatment for menopausal symptoms. High quality evidence confi rms that estrogen effectively treats hot fl ushes, night sweats and vaginal dryness. Progestins are combined with School of Women’s and Infants’ Health The University of Western Australia, estrogen to prevent endometrial hyperplasia and are sometimes used alone for hot fl ushes, King Edward Memorial Hospital, but are less effective than estrogen for this purpose. Data are confl icting regarding the role of Subiaco, Western Australia, Australia androgens for improving libido and well-being. The synthetic steroid tibolone is widely used in Europe and Australasia and effectively treats hot fl ushes and vaginal dryness. Tibolone may improve libido more effectively than estrogen containing HT in some women. We summarize the data from studies addressing the effi cacy, benefi ts, and risks of androgens, progestins and tibolone in the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Keywords: androgens, testosterone, progestins, tibolone, menopause, therapeutic Introduction Therapeutic estrogens include conjugated equine estrogens, synthetically derived piperazine estrone sulphate, estriol, dienoestrol, micronized estradiol and estradiol valerate. Estradiol may also be given transdermally as a patch or gel, as a slow release percutaneous implant, and more recently as an intranasal spray. Intravaginal estrogens include topical estradiol in the form of a ring or pessary, estriol in pessary or cream form, dienoestrol and conjugated estrogens in the form of creams. In some countries there is increasing prescribing of a combination of estradiol, estrone, and estriol as buccal lozenges or ‘troches’, which are formulated by private compounding pharmacists. -

Hormonal and Non-Hormonal Management of Vasomotor Symptoms: a Narrated Review

Central Journal of Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity Review Article Corresponding authors Orkun Tan, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology Hormonal and Non-Hormonal and Infertility, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd. Dallas, TX 75390 and ReproMed Fertility Center, 3800 San Management of Vasomotor Jacinto Dallas, TX 75204, USA, Tel: 214-648-4747; Fax: 214-648-8066; E-mail: [email protected] Submitted: 07 September 2013 Symptoms: A Narrated Review Accepted: 05 October 2013 Orkun Tan1,2*, Anil Pinto2 and Bruce R. Carr1 Published: 07 October 2013 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology Copyright and Infertility, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, USA © 2013 Tan et al. 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, ReproMed Fertility Center, USA OPEN ACCESS Abstract Background: Vasomotor symptoms (VMS; hot flashes, hot flushes) are the most common complaints of peri- and postmenopausal women. Therapies include various estrogens and estrogen-progestogen combinations. However, both physicians and patients became concerned about hormone-related therapies following publication of data by the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study and have turned to non-hormonal approaches of varying effectiveness and risks. Objective: Comparison of the efficacy of non-hormonal VMS therapies with estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) or ERT combined with progestogen (Menopausal Hormone Treatment; MHT) and the development of literature-based guidelines for the use of hormonal and non-hormonal VMS therapies. Methods: Pubmed, Cochrane Controlled Clinical Trials Register Database and Scopus were searched for relevant clinical trials that provided data on the treatment of VMS up to June 2013. -

V3.23 Durable Medical Equipment, Supplies, Vision and Hearing Hardware Nationwide by HCPCS Code

TABLE K. — DURABLE MEDICAL EQUIPMENT, SUPPLIES, VISION AND HEARING HARDWARE NATIONWIDE- CHARGES BY HCPCS CODE v3.23 (January - December 2018) PAGE 1 of 95 Status/ Usage HCPCS Code Modifier 1 HCPCS Code Description Charge GAAF Category Indicator 2 A0100 Blank NONEMERGENCY TRANSPORT TAXI Blank $20.81 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0110 Blank NONEMERGENCY TRANSPORT BUS Blank $61.62 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0120 Blank NONER TRANSPORT MINI-BUS Blank $183.09 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0130 Blank NONER TRANSPORT WHEELCH VAN Blank $85.54 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0140 Blank NONEMERGENCY TRANSPORT AIR Blank $1,211.38 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0160 Blank NONER TRANSPORT CASE WORKER Blank $2.42 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0170 Blank TRANSPORT PARKING FEES/TOLLS Blank $303.72 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0180 Blank NONER TRANSPORT LODGNG RECIP Blank $809.69 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0190 Blank NONER TRANSPORT MEALS RECIP Blank $181.99 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0398 Blank ALS ROUTINE DISPOSBLE SUPPLS Blank $132.93 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A0422 Blank AMBULANCE 02 LIFE SUSTAINING Blank $126.28 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A4206 Blank 1 CC STERILE SYRINGE&NEEDLE Blank $0.94 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A4207 Blank 2 CC STERILE SYRINGE&NEEDLE Blank $0.94 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A4208 Blank 3 CC STERILE SYRINGE&NEEDLE Blank $0.94 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A4209 Blank 5+ CC STERILE SYRINGE&NEEDLE Blank $0.94 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A4210 Blank NONNEEDLE INJECTION DEVICE Blank $1,233.33 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A4211 Blank SUPP FOR SELF-ADM INJECTIONS Blank $57.07 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A4212 Blank NON CORING NEEDLE OR STYLET Blank $13.31 HCPCS - Non-Drugs A4213 Blank 20+ CC SYRINGE ONLY -

State of Connecticut-Department of Social Services

STATE OF CONNECTICUT-DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SERVICES 55 FARMINGTON AVENUE, HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT 06105 Connecticut AIDS Drug Assistance Program (CADAP) Formulary Effective: March 1, 2018 Antiretroviral: Multiclass Single Tablet Regimens Abacavir/ Lamivudine/ Dolutegravir Efavirenz/Emtricitabine/ Tenofovir Disoproxil Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/ Emtricitabine/Tenofovir ( Triumeq ) Fumarate (Atripla ) Disoproxil Fumarate (Stribild ) Bictegravir/ Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Elvitegravir, Cobicistat, Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/ Tenofovir Disoproxil Alafenamide (Biktarvy) Alafenamide (Genvoya ) Fumarate (Complera ) Antiretroviral: Combination Medications Abacavir /Lamivudine (Epzicom) Atazanavir/Cobicistat (Evotaz) Lamivudine/Zidovudine (Combivir) Abacavir/Lamivudine/ Zidovudine Darunavir/Cobicistat (Prezcobix) Lopinavir/Ritonavir (Kaletra) (Trizivir) Emtricitabine/Tenofovir (Truvada) Antiretrovirals: Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor (NRTIs) Medications Abacavir (Ziagen) Emtricitabine (Emtriva) Tenofovir DF (Viread) Didanosine (ddI, Videx, Videx EC) Lamivudine (3TC, Epivir, Epivir HBV ) Zidovudine (AZT, Retrovir ) Stavudine (Zerit) Antiretrovirals: Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor (NNRTIs) Medications Delavirdine Mesylate (Rescriptor) Etravirine (Intelence) Rilpivirine (Edurant) Efavirenz (Sustiva) Nevirapine ( Viramune/Viramune XR ) Antiretrovirals: Protease Inhibitor (PIs) Medications Atazanavir Sulfate (Reyataz) Indinavir (Crixivan) Ritonavir (Norvir) Darunavir (Prezista) Lopinavir/Ritonavir (Kaletra) -

Studies of Cancer in Experimental Animals

ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES, COMBINED 201 3. Studies of Cancer in Experimental Animals In this section, only relevant studies on oestrogens and progestogens alone and in combination that were published subsequent to or not included in Volume 21 of the IARC Monographs (IARC, 1979) are reviewed in detail. Studies reviewed previously are summarized briefly. 3.1 Oestrogen–progestogen combinations 3.1.1 Studies reviewed previously Mouse The results of studies reviewed previously (Committee on Safety of Medicines, 1972; IARC, 1979) on the carcinogenicity of combinations of oestrogens and proges- togens in mice are as follows: Chlormadinone acetate in combination with mestranol tested by oral administration to mice caused an increased incidence of pituitary adenomas in animals of each sex. Oral administration of chlormadinone acetate in combination with ethinyloestradiol to mice resulted in an increased incidence of mammary tumours in intact and castrated males. After oral administration of ethynodiol diacetate and mestranol to mice, increased incidences of pituitary adenomas were observed in animals of each sex. The combination of ethynodiol diacetate plus ethinyloestradiol, tested by oral administration to mice, increased the incidences of pituitary adenomas in animals of each sex and of malignant tumours of connective tissues of the uterus. Lynoestrenol in combination with mestranol was tested in mice by oral administration. A slight, nonsignificant increase in the incidence of malignant mammary tumours was observed in females which was greater than that caused by lynoestrenol or mestranol alone. The combination of megestrol acetate plus ethinyloestradiol, tested by oral adminis- tration to mice, caused an increased incidence of malignant mammary tumours in animals of each sex. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2007/0078091 A1 Hubler Et Al

US 20070078091A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2007/0078091 A1 Hubler et al. (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 5, 2007 (54) PHARMACEUTICAL COMBINATIONS FOR (30) Foreign Application Priority Data COMPENSATING FORATESTOSTERONE DEFICIENCY IN MEN WHILE Sep. 6, 1998 (DE)..................................... 198 2.55918 SMULTANEOUSLY PROTECTING THE PROSTATE Publication Classification (76) Inventors: Doris Hubler, Schmieden (DE): (51) Int. Cl. Michael Oettel, Jena (DE); Lothar A6II 38/09 (2007.01) Sobek, Jena (DE); Walter Elger, Berlin A 6LX 3/57 (2007.01) (DE); Abdul-Abbas Al-Mudhaffar, A6II 3/56 (2006.01) Jena (DE) A 6LX 3/59 (2007.01) A 6LX 3/57 (2007.01) A61K 31/4709 (2007.01) Correspondence Address: A6II 3L/38 (2007.01) MILLEN, WHITE, ZELANO & BRANGAN, (52) U.S. Cl. ............................ 514/15: 514/171; 514/170; P.C. 514/651; 514/252.16; 514/252.17; 22OO CLARENDON BLVD. 514/3O8 SUTE 14OO ARLINGTON, VA 22201 (US) (57) ABSTRACT This invention relates to pharmaceutical combinations for (21) Appl. No.: 11/517,301 compensating for an absolute and relative testosterone defi ciency in men with simultaneous prophylaxis for the devel opment of a benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or prostate (22) Filed: Sep. 8, 2006 cancer. The combinations according to the invention contain a natural or synthetic androgen in combination with a Related U.S. Application Data gestagen, an antigestagen, an antiestrogen, a GnRH analog. a testosterone-5C.-reductase inhibitor, an O-andreno-receptor (63) Continuation of application No. 09/719,221, filed on blocker or a phosphodiesterase inhibitor. In comparison to Feb. 16, 2001, filed as 371 of international application the combinations according to the invention, any active No. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,158,152 B2 Palepu (45) Date of Patent: Apr

US008158152B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,158,152 B2 Palepu (45) Date of Patent: Apr. 17, 2012 (54) LYOPHILIZATION PROCESS AND 6,884,422 B1 4/2005 Liu et al. PRODUCTS OBTANED THEREBY 6,900, 184 B2 5/2005 Cohen et al. 2002fOO 10357 A1 1/2002 Stogniew etal. 2002/009 1270 A1 7, 2002 Wu et al. (75) Inventor: Nageswara R. Palepu. Mill Creek, WA 2002/0143038 A1 10/2002 Bandyopadhyay et al. (US) 2002fO155097 A1 10, 2002 Te 2003, OO68416 A1 4/2003 Burgess et al. 2003/0077321 A1 4/2003 Kiel et al. (73) Assignee: SciDose LLC, Amherst, MA (US) 2003, OO82236 A1 5/2003 Mathiowitz et al. 2003/0096378 A1 5/2003 Qiu et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2003/OO96797 A1 5/2003 Stogniew et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2003.01.1331.6 A1 6/2003 Kaisheva et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 1560 days. 2003. O191157 A1 10, 2003 Doen 2003/0202978 A1 10, 2003 Maa et al. 2003/0211042 A1 11/2003 Evans (21) Appl. No.: 11/282,507 2003/0229027 A1 12/2003 Eissens et al. 2004.0005351 A1 1/2004 Kwon (22) Filed: Nov. 18, 2005 2004/0042971 A1 3/2004 Truong-Le et al. 2004/0042972 A1 3/2004 Truong-Le et al. (65) Prior Publication Data 2004.0043042 A1 3/2004 Johnson et al. 2004/OO57927 A1 3/2004 Warne et al. US 2007/O116729 A1 May 24, 2007 2004, OO63792 A1 4/2004 Khera et al.