Settling Water Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Treatment and Reverse Osmosis Systems

Pure Aqua, Inc.® Water© 2012 TreatmentPure Aqua ,and Inc. ReverseAll Right sOsmosis Reserve dSystems. Worldwide Experience Superior Technology About the Company Pure Aqua is a company with a strong philosophy and drive to develop and apply solutions to the world’s water treatment challenges. We believe that both our technology and experience will help resolve the growing shortage of clean water worldwide. Capabilities and Expertise As an ISO 9001:2008 certified company with over a decade of experience, Pure Aqua has secured its position as a leading manufacturer of reverse osmosis systems worldwide. Goals and Motivations Our goal is to provide environmentally sustainable systems and equipment that produce high quality water. We provide packaged systems and technical support for water treatment plants, industrial wastewater reuse, and brackish and seawater reverse osmosis plants. Having strong working relationships with Thus, we ensure our technological our suppliers gives us the capability to contribution to water preservation by provide cost effective and competitive supplying the means and making it highly water and wastewater treatment systems accessible. for a wide range of applications. Seawater Reverse Osmosis Systems System Overview Designed to convert seawater to potable water, desalination systems use high quality reverse osmosis seawater membranes. The process separates dissolved salts by only allowing pure water to pass through the membrane fabric. System Capacities Pure Aqua desalination systems are designed to provide high -

Cost Analysis of the Impacts on Municipal Utilities and Biosolids Management to Address PFAS Contamination

Cost Analysis of the Impacts on Municipal Utilities and Biosolids Management to Address PFAS Contamination October 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary Section 1 Background 1.1 Biosolids ................................................................................................................................................................ 1-1 Section 2 Data on Actual Costs to Wastewater and Biosolids Management Programs from PFAS 2.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 NEBRA Survey ..................................................................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 2-1 2.2.2 Results ...................................................................................................................................................... 2-2 2.3 Expanded Utility Survey ................................................................................................................................. 2-2 2.3.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 2-2 2.3.2 Results ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Landfill Leachate Pretreatment Process Evaluation and Pilot Study

Landfill Leachate Pretreatment Process Evaluation and Pilot Study Richard Claus – Hazen and Sawyer, P.C. John Butler – Rumpke Consolidated Companies, Inc. Dan Miklos – Hazen and Sawyer, P.C. Presentation Overview Part 1 – Overview of Study, Piloting, and Design Introduction Timeline of Study, Evaluation, & Disposal Wastewater Characterization & Pretreatment Study Timeline of Piloting and Design Pretreatment Design Presentation Overview Part 2 – Pilot Treatment Sessil Media Trickling Filter Pilot Chemical Treatment Jar Testing and Pilot Considered ElectroCell Piloting Next Steps Introduction Rumpke Sanitary Landfill Cincinnati, OH, Colerain Township, Northwest Hamilton County Rumpke Consolidated Companies, Inc. Family Owned, Operated since 1945 One of the largest landfills in the nation, largest in Ohio Rumpke Colerain Township Landfill Introduction Northwest Area Landfill Portion of landfill undergoing a reaction since August, 2009 Source of extremely strong leachate Averaging 120-degrees Fahrenheit Average Volumes of 120,000 GPD (2010-2011) to 200,000 GPD (2012) Northwest Lift Station Lift Station No. 2 Pilot and Tanker Loadout Locations Northwest Area Landfill Introduction – NW Area Leachate Current Characteristics COD 30,000 to 50,000 mg/L BOD5 20,000 to 30,000 mg/L TSS 1,000 – 2,000 mg/L TKN 1,500 – 2,500 mg/L Fe 250 – 700 mg/L Ca 1,500 – 3,700 mg/L Temperature 120 degrees F Introduction – NW Area Leachate On –Going Issues Pipe scaling/clogging during conveyance Odors during handling/disposal Costs for disposal Study, Evaluation, and Disposal Timeline August, 2009 – Increasing leachate strength from Northwest Area August, 2010 to May, 2011 – Wastewater Characterization & Pretreatment Study August, 2011 to June, 2012 – Treatment Piloting and Pretreatment Design Study, Evaluation, and Disposal Timeline - Continued Historically until October 7, 2011 – “Blended” Flow Sewer Discharge into MSDGC Collection System NW Area Leachate (Approx. -

Package Plants Arrive on Site Virtually Ready to Operate and Built to Minimize the Day-To-Day Attention Required to Operate the Equipment

A NATIONAL DRINKING WATER CLEARINGHOUSE FACT SHEET Package Plants Summary Small water treatment systems often find it difficult to comply with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations. Small communities often face financial problems in purchas- ing and maintaining conventional treatment systems. Their problem is further complicated if they do not have the services of a full-time, trained operator. The Surface Water Treatment Rule (SWTR) requirements have greatly increased interest in the possible use of package plants in many areas of the country. Package plants can also be applied to treat contaminants such as iron and manganese in groundwater via oxidation and filtration. ○○○○○○○○○○ Package Plants: Alternative to Conventional Treatment What is a package plant? How To Select a Package Plant Package technology offers an alternative to Package plant systems are most appropriate for in-ground conventional treatment technology. plant sizes that treat from 25,000 to 6,000,000 They are not altogether different from other gallons per day (GPD) (94.6 to 22,710 cubic treatment processes although several package ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ meters per day). Influent water quality is the plant models contain innovative treatment most important consideration in determining elements, such as adsorptive clarifiers. The the suitability of a package plant application. primary distinction, however, between package Complete influent water quality records need plants and custom-designed plants is that to be examined to establish turbidity levels, package plants are treatment units assembled seasonal temperature fluctuations, and color in a factory, skid mounted, and transported level expectations. Both high turbidity and color to the site. may require coagulant dosages beyond many package plants design specifications. -

Evaluation of Azeotropic Dehydration for the Preservation of Shrimp. James Edward Rutledge Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1969 Evaluation of Azeotropic Dehydration for the Preservation of Shrimp. James Edward Rutledge Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Rutledge, James Edward, "Evaluation of Azeotropic Dehydration for the Preservation of Shrimp." (1969). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1689. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1689 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 70-9089 microfilmed exactly as received RUTLEDGE, James Edward, 1941- EVALUATION OF AZEOTROPIC DEHYDRATION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF SHRIMP. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, PhJD., 1969 Food Technology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Evaluation of Azeotropic Dehydration for the Preservation of Shrimp A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Food Science and Technology by James Edward Rutledge B.S., Texas A&M University, 1963 M.S., Texas A&M University, 1966 August, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to express his sincere appreciation to his major professor, Dr, Fred H. Hoskins, for the guidance which he supplied not only in respect to this dissertation but also in regard to the author’s graduate career at Louisiana State University, Gratitude is also extended to Dr. -

Assessment of End-Of-Life Opportunities for Reverse Osmosis

Assessment of End-of-Life Opportunities for Reverse Osmosis Membranes Will Lawler A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Chemical Engineering Faculty of Engineering March 2015 i. Abstract Reverse osmosis (RO) membranes are now core to modern desalination processes and are widely used around the world. Based on the increasing number of desalination plants, and the finite lifespan of the membranes, the resulting number of used RO modules to be discarded is becoming a critical challenge. The overall aim of this study is to identify, develop and assess alternative end-of-life options for used RO elements and investigate the associated technical readiness, environmental impact, financial considerations and legislative challenges. The assessed end-of-life alternatives include, direct reuse of the old membranes within lower throughput systems; chemical conversion into porous, ultrafiltration (UF) like filters; direct reuse or recycling of the various module components; various energy recovery techniques, and landfill disposal. The results show that direct reuse is a promising application that can be utilised with minimal additional treatment or infrastructure; however, module storage techniques are a critical consideration, particularly as membrane drying has a significant and irreversible impact on membrane performance due to pore collapse in the polysulfone support layer. The method for chemical conversion with controlled exposure to NaOCl has been optimised, resulting in promising organic and virus removal properties, comparable to commercially available 10 – 30 kDa molecular weight cut off UF membranes; however, there was significant variation in hydraulic performance, ranging from 8 – 400 L.m-2.h-1.bar-1. -

Flash Column Chromatography Guide

8.9 - Flash Column Chromatography Guide Overview: Flash column chromatography is a quick and (usually) easy way to separate complex mixtures of compounds. We will be performing relatively large scale separations in 5.301, around 1.0 g of compound. Columns are often smaller in scale than this and some of you will experience these once you move into the research lab. Column chromatography uses the same principles discussed in the TLC Handout, but can be used on a preparative scale. We are running flash columns since we will use compressed air to push the solvent through the column. This not only helps provide better separation, but also cuts down the amount of time required to run a column. Reading: For an excellent description, see LLP pages 205 - 214. Preparing and Running a Flash Column: 1) Determine the dry, solvent-free weight of the mixture that you want to separate. 2) Determine the solvent system for the column by using TLC (see TLC Handout). You should aim for Rf values between 0.2 and 0.3. If your mixture is complicated then this may not be possible. In complex cases, you will probably have to resort to gradient elution. This simply means that you increase the polarity of the solvent running through the column (eluent) throughout the course of the purification. This technique will be described in more detail later in the handout, but for the TLC analysis you should determine which solvent systems put the different spots in the 0.2 to 0.3 Rf range. 3) Determine the method of application to the column. -

Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture: Good Practice Examples

SAFE USE OF WASTEWATER IN AGRICULTURE: GOOD PRACTICE EXAMPLES Hiroshan Hettiarachchi Reza Ardakanian, Editors SAFE USE OF WASTEWATER IN AGRICULTURE: GOOD PRACTICE EXAMPLES Hiroshan Hettiarachchi Reza Ardakanian, Editors PREFACE Population growth, rapid urbanisation, more water intense consumption patterns and climate change are intensifying the pressure on freshwater resources. The increasing scarcity of water, combined with other factors such as energy and fertilizers, is driving millions of farmers and other entrepreneurs to make use of wastewater. Wastewater reuse is an excellent example that naturally explains the importance of integrated management of water, soil and waste, which we define as the Nexus While the information in this book are generally believed to be true and accurate at the approach. The process begins in the waste sector, but the selection of date of publication, the editors and the publisher cannot accept any legal responsibility for the correct management model can make it relevant and important to any errors or omissions that may be made. The publisher makes no warranty, expressed or the water and soil as well. Over 20 million hectares of land are currently implied, with respect to the material contained herein. known to be irrigated with wastewater. This is interesting, but the The opinions expressed in this book are those of the Case Authors. Their inclusion in this alarming fact is that a greater percentage of this practice is not based book does not imply endorsement by the United Nations University. on any scientific criterion that ensures the “safe use” of wastewater. In order to address the technical, institutional, and policy challenges of safe water reuse, developing countries and countries in transition need clear institutional arrangements and more skilled human resources, United Nations University Institute for Integrated with a sound understanding of the opportunities and potential risks of Management of Material Fluxes and of Resources wastewater use. -

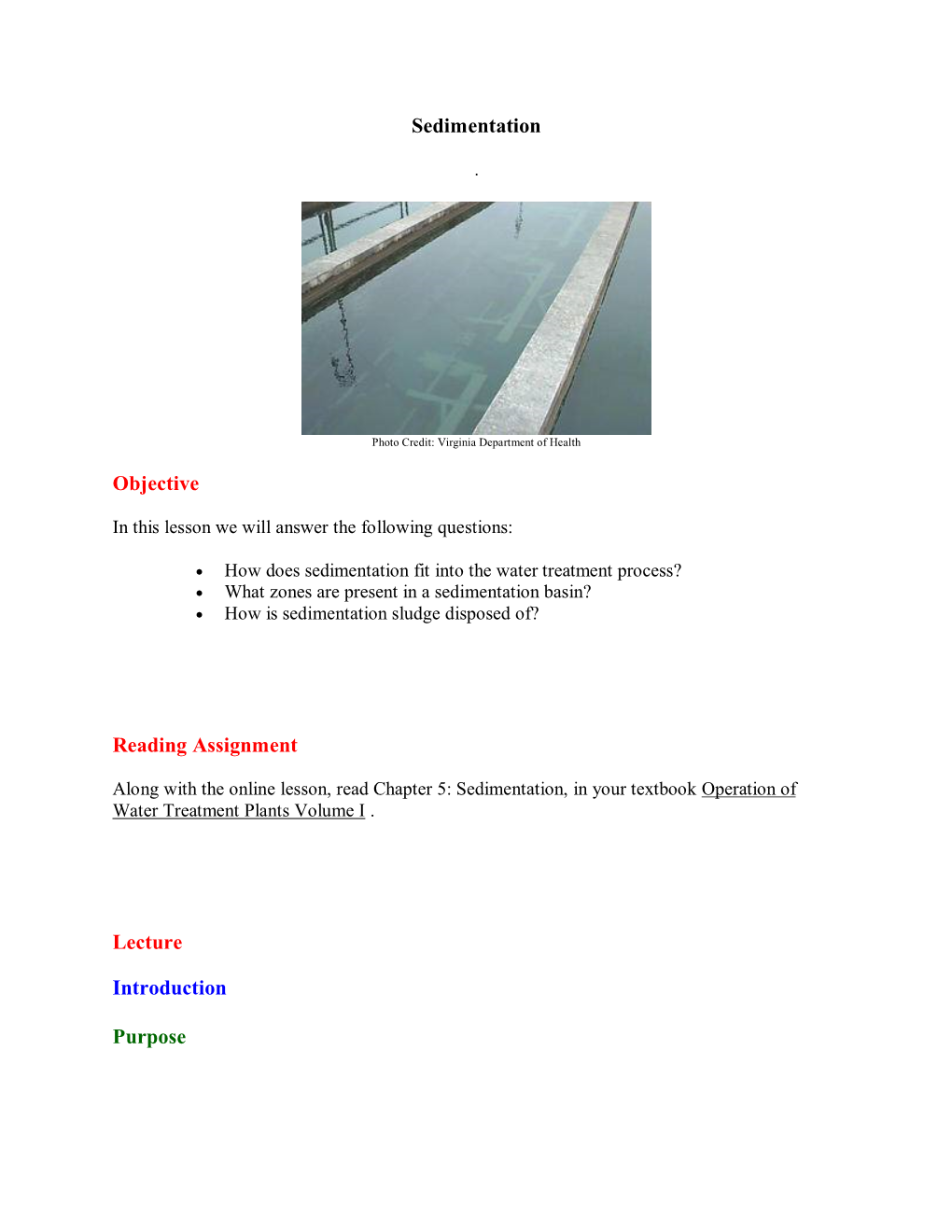

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation Is the Next Step in Conventional Filtration Plants

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation is the next step in conventional filtration plants. (Direct filtration plants omit this step.) The purpose of sedimentation is to enhance the filtration process by removing particulates. Sedimentation is the process by which suspended particles are removed from the water by means of gravity or separation. In the sedimentation process, the water passes through a relatively quiet and still basin. In these conditions, the floc particles settle to the bottom of the basin, while “clear” water passes out of the basin over an effluent baffle or weir. Figure 7-5 illustrates a typical rectangular sedimentation basin. The solids collect on the basin bottom and are removed by a mechanical “sludge collection” device. As shown in Figure 7-6, the sludge collection device scrapes the solids (sludge) to a collection point within the basin from which it is pumped to disposal or to a sludge treatment process. Sedimentation involves one or more basins, called “clarifiers.” Clarifiers are relatively large open tanks that are either circular or rectangular in shape. In properly designed clarifiers, the velocity of the water is reduced so that gravity is the predominant force acting on the water/solids suspension. The key factor in this process is speed. The rate at which a floc particle drops out of the water has to be faster than the rate at which the water flows from the tank’s inlet or slow mix end to its outlet or filtration end. The difference in specific gravity between the water and the particles causes the particles to settle to the bottom of the basin. -

Settling-Thickening Tanks

Chapter 6 Settling-Thickening Tanks Pierre-Henri Dodane and Magalie Bassan Technology Learning Objectives • Understand in what contexts settling-thickening tanks are an appropriate treatment technology. • Understand the fundamental mechanisms of how settling-thickening tanks function. • Have an overiew of potential advantages and disadvantages of operating a settling-thickening tank. • Know the appropriate level of operations, maintenance and monitoring necessary to achieve solids-liquid separation in settling-thickening tanks. • Be able to design a settling-thickening tank to achieve the desired treatment goal. 6.1 INTRODUCTION Settling-thickening tanks are used to achieve separation of the liquid and solid fractions of faecal sludge (FS). They were fi rst developed for primary wastewater treatment, and for clarifi cation following secondary wastewater treatment, and it is the same mechanism for solids-liquid separation as that employed in septic tanks. Settling-thickening tanks for FS treatment are rectangular tanks, where FS is discharged into an inlet at the top of one side and the supernatant exits through an outlet situated at the opposite side, while settled solids are retained at the bottom of the tank, and scum fl oats on the surface (Figure 6.1). During the retention time, the heavier particles settle out and thicken at the bottom of the tank as a result of gravitational forces. Lighter particles, such as fats, oils and grease, fl oat to the top of the tank. As solids are collected at the bottom of the tank, the liquid supernatant is discharged through the outlet. Quiescent hydraulic fl ows are required, as the designed rates of settling, thickening and fl otation will not occur with turbulent fl ows. -

Troubleshooting Activated Sludge Processes Introduction

Troubleshooting Activated Sludge Processes Introduction Excess Foam High Effluent Suspended Solids High Effluent Soluble BOD or Ammonia Low effluent pH Introduction Review of the literature shows that the activated sludge process has experienced operational problems since its inception. Although they did not experience settling problems with their activated sludge, Ardern and Lockett (Ardern and Lockett, 1914a) did note increased turbidity and reduced nitrification with reduced temperatures. By the early 1920s continuous-flow systems were having to deal with the scourge of activated sludge, bulking (Ardem and Lockett, 1914b, Martin 1927) and effluent suspended solids problems. Martin (1927) also describes effluent quality problems due to toxic and/or high-organic- strength industrial wastes. Oxygen demanding materials would bleedthrough the process. More recently, Jenkins, Richard and Daigger (1993) discussed severe foaming problems in activated sludge systems. Experience shows that controlling the activated sludge process is still difficult for many plants in the United States. However, improved process control can be obtained by systematically looking at the problems and their potential causes. Once the cause is defined, control actions can be initiated to eliminate the problem. Problems associated with the activated sludge process can usually be related to four conditions (Schuyler, 1995). Any of these can occur by themselves or with any of the other conditions. The first is foam. So much foam can accumulate that it becomes a safety problem by spilling out onto walkways. It becomes a regulatory problem as it spills from clarifier surfaces into the effluent. The second, high effluent suspended solids, can be caused by many things. It is the most common problem found in activated sludge systems. -

PFAS in Influent, Effluent, and Residuals of Wastewater Treatment Plants (Wwtps) in Michigan

Evaluation of PFAS in Influent, Effluent, and Residuals of Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) in Michigan Prepared in association with Project Number: 60588767 Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy April 2021 Evaluation of PFAS in Influent, Effluent, and Residuals of Project number: 60588767 Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) in Michigan Prepared for: Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy Water Resources Division Stephanie Kammer Constitution Hall, 1st Floor, South Tower 525 West Allegan Street P.O. Box 30242 Lansing, MI 48909 Prepared by: Dorin Bogdan, Ph.D. Environmental Engineer, Michigan E-mail: [email protected] AECOM 3950 Sparks Drive Southeast Grand Rapids, MI 49546 aecom.com Prepared in association with: Stephanie Kammer, Jon Russell, Michael Person, Sydney Ruhala, Sarah Campbell, Carla Davidson, Anne Tavalire, Charlie Hill, Cindy Sneller, and Thomas Berdinski. Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy Water Resources Division Constitution Hall 525 West Allegan P.O. Box 30473 Lansing, MI 48909 Prepared for: Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy AECOM Evaluation of PFAS in Influent, Effluent, and Residuals of Project number: 60588767 Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) in Michigan Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background ........................................................................................................................................